wadoryu

Is Wado really a style of Karate?

I am publishing this post on here as an example of the more focussed articles I have lined up for the Substack project. My postings on Substack will eventually be on two levels; free content that comes out every week and content that can be accessed by a small paid monthly subscription, believe me, it will be worth it. If you haven’t already, sign up free for the project at, https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

Btw. If you are signed up and on Gmail, be wary that it has a habit of dropping Substack posts into the ‘Promotions’ folder.

On with the theme.

Everything has to fit into some kind of category; labels must be attached and pigeonholes have to be filled – otherwise how do we know what we are describing. It is a quick way to make sense of things, particularly if we want to communicate to other people what we are talking about.

The quick shorthand operates largely because we are in a hurry – someone asks, “What do you do with your evenings?”, answer, “I go to my karate class”. The conversation could end at that point, or the questioner might ask for more information, out of politeness or maybe they are genuinely interested. And that is your opportunity to volunteer more detail.

Do we want Wado to be called ‘karate’?

But we Wado people are likely to be entirely happy to allow what we do to be identified as ‘karate’. But, is Wado Ryu/Kai etc really karate? Maybe it is something else which has not been truly pinned down, like a newly discovered genus; a wild critter that is neither ‘dog’ nor ‘cat’, a kind of Tasmanian Tiger, but still kicking around, possibly even thriving? [1]

It is entirely possible that Wado sails under a flag of convenience? I have cousins who hold both US and UK citizenship and I can’t help noticing that when they are in the UK they fly the US flag and when in the USA they fly the British flag when it suits them (really noticeable when the accents change). With Wado it very much the same; being identified as ‘karate’ has opened many doors for them, but what about its other possible identifying qualities, what are the competing factions?

Let me try and lay out the case… with some provisos, I am not Japanese and I run the risk of looking at this from a very western viewpoint, so everything here is conjecture and opinion.

Let me start with the easy one:

Wado as Japanese Budo.

This is where we apply the national pride and cultural credentials to Wado. It has such deep roots that to explain it would be like trying to untangle spaghetti. This is the bigger ‘identity’ issue. ‘But Wado was only recognised as an entity in 1938’! – I hear you say. Maybe, but, as we will see, the complexity of the history of Japan’s own indigenous martial systems is not to be taken lightly, particularly as it applies to Wado.

Personally, I quite like the ‘Wado is a distinct form of very Japanese Budo’ angle; it ties it neatly to the unquestioning high cultural and moral characteristics of anything that falls into the category ‘Budo’. But, as we know ‘Budo’ is a broad grouping and can be annoyingly difficult to pin down, especially when it uses high-minded and sometimes vague terms in which to describe itself.

But the subtext here should not be skipped over too quickly – ‘distinctly Japanese’, we are now talking about Budo as a kind of cultural artefact, one that has to be wrapped in the flag. But ‘distinct from’ what?

Historically, indigenous Japanese arts have had their heyday, and since Japan took to embracing all things western, these ‘arts’ slipped in the category of anachronisms; they were considered out of step with the direction Japan saw itself going in. For industrial Japan there was no going back, and, it has to be said, the Japanese performed economic and technical miracles; certainly, pre WW2, where things then went more than a little sideways.

Then came a time when these ancient arts needed to either be rescued from decline or completely resurrected, and, in the marketplace for oriental martial arts they had to stand up for themselves and proclaim who they were. This ‘claiming of the national identity’ came a lot earlier than most people think; it could be said that ‘karate’ was the first skirmish in a culture war that was yet to happen.

To keep this brief; Karate was from Okinawa, with very strong cultural ties to China, one of the earlier incarnations of the characters used to write ‘karate’ was actually ‘Chinese Hand’, so effectively this was an imported system and, considering the rocky historical relationship between China and Japan (which was to get a whole lot worse before it got better), this was not a welcome import in conservative eyes. (This all happened around 1922 and, if you’d asked someone in a Tokyo street prior to that date about ‘karate’, they’d say they’d never heard of it, it only existed in the Okinawan islands [2])

‘Karate’ had to have an image make-over to make it palatable. Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado, was a key mover in this area. He (and others) helped to make the necessary adjustments and secure karate in Japan as something the establishment would welcome.

Otsuka Hironori Sensei managed to eventually unshackle himself from the Okinawan karate system that he had previously been so eager to embrace (whether by accident, fortune or design is open to speculation) and from that base and his martial cultural roots in Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, he was able to craft something new, something distinctive, and was entirely happy to describe it as ‘Japanese Budo’ (while still holding on to the ‘karate’ moniker).

Ducks and Zebras.

‘If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck and looks like a duck…it’s a duck’. Take a quick look at the qualities that the casual observer would see in Wado karate, a kind of comparative checklist; what is it you find in most styles of karate?

- An emphasis on punching, kicking and striking; which lends itself well to a sport format.

- A training regime which includes solo kata, which all follow a similar external structure and hold on to original names which define their Okinawan origins.

- A training uniform that would not be out of place in any karate Dojo in any style in the world.

Bear with me on this one; the saying, ‘When you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras’. This is told to trainee doctors, reminding them to think when diagnosing, of the most common, hence the most obvious answer. But I recently heard a doctor explaining how this idea was of limited use and how she had once misdiagnosed a patient suffering from a rare condition. Is Wado perhaps the zebra?

Take another look at the above checklist; all but the second point can be explained away; firstly, striking and kicking are not unique to karate. Secondly, it was Otsuka who was one of the main movers in pushing towards a sport format [3]. And thirdly; the uniform (Keikogi) was just a convenient design development that happened over decades, which was inevitable really.

Point 2 has been chewed over a lot by karate people, both Wado and non-Wado, but I will offer my view in a nutshell. Otsuka saw something in the karate kata that he could use. What he wanted was a framework, no need to reinvent the wheel. What was really clever was that he transposed his own ideas on top of that framework, which, interestingly, was hugely at odds with how the other karate schools/styles used it.

Wado as Jujutsu.

Why would that even be considered?

Evidence?

The second grandmaster of Wado Ryu Otsuka Hironori II at some point decided to re-register the name of his school with the authorities (probably the Dai Nippon Butokukai) and call it ‘Wado Ryu Jujutsu Kempo’. So ‘karate’ was dropped completely and ‘Jujutsu’ was added. I am not going to second guess or explain the reason for this, I am not Japanese and I am not versed in the Japanese martial arts political world, but I will speculatively introduce a few thoughts from a very western perspective (always dangerous).

Firstly, apply a similar checklist to the one above, but for Jujutsu, and, from a casual lazy western perspective, nothing stacks up.

The first grandmaster and creator did indeed add a catalogue of standard Judo/Jujutsu techniques to the original list he had to present to the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938, but these were largely dropped (the exceptions being the Idori and the Tanto Dori). But, my observations tell me that it would be a mistake to assume that this is all there is to traditional Japanese Jujutsu, the complexity goes much further than Jujutsu tricks [4].

What about the word ‘Kempo’ (or ‘Kenpo’). Actually, this has a long history in Japanese martial arts.

The term Jujutsu did not really exist as a distinct entity in Japan until the early 17th century, before that a whole bunch of other terms were used; kumiuchi, yawara, taijutsu, kogusoku and kempo. ‘Kempo’ is just the Japanese version of the Chinese Chuan Fa, or ‘Fist Way’. This does not mean that Kempo is from Chinese boxing, that is a rabbit hole not worth going down. There is however a strong link with the striking aspect of Old School Japanese martial traditions, often associated with Atemi Waza, the art of attacking anatomical weak points with both hand and foot. There is a suggestion that Otsuka Sensei was really skilled at this prior to his first exposure to Okinawan karate and that his first Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu teacher, Nakayama Tatsusaburo was somewhat of on an expert in this field.

A conversation with someone closer to the source also suggested that the word ‘Kempo’ had been around earlier in the history of the formulation of the distinct identity of Wado, but I have been unable to verify this with documented evidence.

All of this tips the scales in favour of the inclusion of the word ‘Kempo’, but, this is just my opinion, there has to be more to it than that, there always is.

One more piece of evidence to muddy the water.

When master Otsuka had to register his school with the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938 he officially recognised one Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki the semi-mythical founder of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu as the founder of Wado Ryu, rather than himself. This might not be as unusual or controversial as it sounds. Firstly, there is the Okinawan/Japanese problem, so this is a smart political way of painting Wado in the right colour to be accepted in the highly conservative establishment of the Butokukai. But, Otsuka Sensei himself explained this point; saying that, because the actual ‘founder’ of karate was unknown, his best option was to name Akiyama. [5] The suggestion being, I suppose, that the Yoshin Ryu (SYR) component of Otsuka’s new synthesis was significant enough to make this entirely permissible.

There is also an historical precedent, well in theory anyway, this is to do with one of the early branches of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, not so very far removed from Otsuka Sensei’s root art of Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu.

In the 1700’s one Oi Senbei Hirotomi seems to have picked up the reins of what was established as ‘Aikiyama Yoshin Ryu’; a theory goes that in his efforts to claim a direct lineage for his curriculum he also used the Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki name in a more blatant way than just applying it to the signboard of his school, he used his name as official founder. This may have been to deflect attention away from any thoughts that his own teachings were a blend of other influences by actually saying that Akiyama was the real founder of the Ryu not Oi Senbei! Was this done out of modesty or deception? Was it even true? Who knows. It is one those mysteries that will never be answered.

Ellis Amdur puts other theories forward, suggesting that by placing a semi-mythical person as figurehead you create space to allow your new development/style/school to stand on its own feet and to become established without the glare of unnecessary criticism or accusations of immodesty. Is this perhaps in part, what Otsuka Sensei was doing. [6]

In conclusion, just what is Wado? New species, sub species, synthesis or something that defies categorisation? And, the final question; does it even matter?

Tim Shaw

[1] Tasmanian Tiger (extinct 1936), it looks like a skinny wolf, but it has stripes down its back like a tiger; in fact it was a kind of carnivorous marsupial.

[2] If you said ‘Kempo’ you might get a glimmer of recognition.

[3] Wado wants to play in the ‘sport/competition’ sandpit? Call it ‘karate’ and the door opens, it’s all very clever politically.

[4] At the time many of the listed techniques were common knowledge, even to schoolchildren, but that doesn’t make them any less difficult.

[5] Source; ‘Karate Wadoryu – from Japan to the West’ Ben Pollock 2020. An excellent resource. Who in turn drew his reference from, ‘Karate-Do Volume 1’ Hironori Otsuka 1970.

[6] Source ‘Old School’ Ellis Amdur and further commentary from Mr Amdur at https://kogenbudo.org/how-many-generations-does-it-take-to-create-a-ryuha/

Humbled Daily.

Before I launch into this latest blog theme, just a quick word about a new development.

I wanted to extend this writing project into something bigger and so have set up on Substack, a subscription service which is really taking off. I will write a following blog post to outline my plans, but basically it is already up and running. Please support this new project. It can be found at: https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

On with the theme…

In a recent interview with movement guru Ido Portal he mentioned that grapplers and wrestlers get humbled daily, and it was a healthy thing. They roll on the mat with people of different abilities and frequently experience the challenges that such opportunities present. Often, they fail in their intentions; frequently someone else’s intentions win over theirs and they experience failure. In fact, an intense session may well involve a rolling series of mini-victories and mini-defeats. These are all valuable growth experiences. [1]

Portal says that this seldom happens in traditional martial arts, and he’s right. While not being entirely absent, it certainly doesn’t happen to that intensity.

In traditional martial arts very often the training scenario is so tightly directed that there is little space for this type of training; or, in some cases ‘loss’ is too high a price to pay that it is actually demonised, or only seen for its negative attributes.

What are the real obstacles for us as traditional martial artists to engage in parallel ‘humbling’ interchanges? Here is a list of the potential problems:

- Attitude, this might be related to ego, rank, status etc. I find it ironic that ‘humility’ in Budo is seen as a positive attribute, yet the aforementioned attitude problems are allowed space in the Dojo.

- Avoidance. We know the phrase ‘risk averse’, if you don’t willingly embrace challenge it’s going to be very difficult to improve. [2]

- The constrictions of the training format. We know that our training in traditional martial arts is limited by having to fit so much into a limited time; our priority has to be the syllabus as this is the framework upon which everything depends. How to overcome these limitations often falls on the creativity of the Sensei. Some are good at this, others not so.

- The absence of ‘Play’. Often derided, but, if we think about it, some of our most powerful learning experiences have come to us through play – we only have to think of the physical challenges of our childhood.

And what about competition and sport?

The demonisation of ‘loss’ is perhaps amplified when martial arts become sports. Although, today there is a trend where everybody has to be a winner, it’s an illogical formula. I will counter this with the pro-hierarchy viewpoint. If there is no ladder-like hierarchy to climb then there is no value system. When everything becomes the same worth there’s nothing to aspire to, no striving, no reaching, the whole enterprise becomes meaningless.

In a karate competition the winner’s position becomes of value because of everyone who pitched in and competed on that day. The winner should feel genuine gratitude towards all of those who competed against him or her, it was their efforts that elevated the champion to that top position. And, although all of those people don’t get the trophy or the accolades, they gain so much in the experience of just competing. This is the true ‘everybody is a winner’ approach.

In a healthy Dojo environment instructors are beholden to devise ever more creative ways of training to allow students to experience lots of free-flowing exchanges, where mistakes are seen as learning experiences. A while back, I shamelessly stole a phrase from an ex-training buddy who was from another system. He called this stuff ‘flight time’, as in, how trainee pilots clock up their hours of developing experience. If you get the balance right nothing is wasted in well designed ‘flight time’ in the Dojo. Over the last ten years or so I have been working on different methods of creating condensed ‘flight time’ experiences. When it’s going well there are continually unfolding successes and failures, and the best part of it is that during training everybody gets it wrong sometimes and therefore has to learn to savour the taste of Humble Pie.

Bon Appetit.

Tim Shaw

[1] I have heard similar things from the early days of Kodokan Judo, hours and hours of rolling and scrambling with opponent after opponent.

[2] ‘Invest in loss’ is a phrase often heard among Tai Chi people. It describes the lessons learned from failure. The late Reg Kear told a story about his experiences with the first grandmaster of Wado Ryu, who said something similar to, ‘when thrown to the floor, pick up change’ and then, with a smile, mimed biting into a coin.

Featured images from ‘The Manual of Judo’, E. J. Harrison 1952.

How detailed is your Wado map?

How confident are you about what you know of your system, the discipline you have chosen to study? Are you comfortable with the information you currently have to hand? Do you think you understand the roadmap of that developing knowledge, and is its trajectory obvious and predictable?

Okay, so, I accept that any Wado practitioner reading this might well be at very different points in their journey; some may be just beginning their study, others might be senior practitioners with many years behind them, but the ideas I am going to put forward I am fairly sure would benefit all – or at least stop and make you think. That’s the plan anyway.

Maps.

I am going to start with the broader idea, something I heard a little while ago. There is a theory that we all keep a complete map of the world within our own heads – a personal hardwired version like Google Satellite, Street View and Maps. When I first heard this, I was sceptical.

While I am fully aware that the human brain is perhaps the most complex thing on the planet but really this seemed a bit too far-fetched. But, it is true. That mess of grey matter that sits between our ears that has no awareness of itself outside of its own input devices – our senses, can really do all that, and more!

This amazing mapping, navigation device does not just include places, it also acts as our own personal encyclopaedia, with just about everything there is to be referenced. I use the word ‘referenced’ in a very deliberate way because the reality is that ‘references’ are about all we get.

To explain; while we have this map/encyclopaedia in our head most of this information is patchy and, in many cases, extremely low-resolution. The truth is, we have low-resolution representations of the majority of things we think we know.

Examples:

- Ask yourself about a random country in the world; say, Vietnam? Can you point to it on a map? Probably, but what else can your personalised encyclopaedia tell you? History, culture, language, currency? Unless you know the country very well through direct experience your knowledge will be sketchy, very low-resolution.

- Another couple of words; ‘Steam Train’. To communicate your understanding of this mode of transport, you might draw me a picture of a steam train, complete with funnel and wheels and a cab, all very ‘Thomas the Tank Engine’ – but unless you are an insanely enthusiastic trainspotter with qualifications in engineering and skills in mechanical draughtsmanship, I am not going to be convinced that you really understand a steam train, it will be extremely low-resolution.

Okay, so there are things we might be VERY knowledgeable about (or THINK we are), but the reality of our ‘wired-in’ intelligence and retrieval system (brain) is that it is in a state of constant update, or at least it should be. The truth is that (hopefully) more depth of information is being added and redundant (false) files are being deleted or replaced and new entries or categories are being added.

In some areas, people actually choose not to update their maps and files, this is often found when people become entrenched in areas like politics. Clearly, individuals can be so profoundly tribal in their political beliefs that even in the face of irrefutable evidence they will argue that black is white. But that’s their problem.

How about Wado (or any martial arts system)?

All of the above can be applied to our understanding of Wado karate.

I think it’s a case of being totally honest with yourself; particularly those who have been on this pathway a long time. Come on, do you really believe the same things that you did twenty years ago? How have your files been updated?

An example:

I came to the conclusion a long time back that just about everyone I knew in the martial arts continued their training for completely different reasons than those they started with. It might have been that they initially wanted to build confidence; they were fearful about their ability to protect themselves; but then, over time, their maps changed, their references became more sophisticated, more nuanced and they found something new, something of substance. I can’t get into describing what that is in this post, I don’t have the space; (in some ways I explored this idea in my blog post ‘Martial Arts training and the value of finding your Tribe.’).

Your Wado map.

For every student of Wado karate your initial ‘map’ is usually found in the pages of your syllabus book. This map expands as you move through the grades. Although, I must say, the reality is, it’s not an easily accessible map because it is mostly written in a different language.

But it would be naïve to assume that when we have completed the book we have mastered the system, it doesn’t work like that. The syllabus is a very low-resolution representation of the system; really, it’s a loose framework designed for convenience. In addition, ‘knowing’ the book, with its Kihon, Kata and Kumite doesn’t guarantee you can actually do it; and doing it doesn’t mean you can apply it. Imagine a musician who can read sheet music but can’t play an instrument, or who can play the music accurately but cannot improvise!

The downside of the syllabus book.

In Wado I don’t think reliance on the syllabus book is particularly helpful; it’s a pretty poor map. For me it’s too linear. For systems other than Wado it might easily describe the structure in a straightforward and accurate way, but within Wado karate it only takes you so far in understanding the true nature of this very unique Japanese Budo system. In fact, I would go so far as to say that if the book is the only model/access route, it will ultimately lead you down a dead end. [1]

A different map.

In some of my more recent teaching seminars I have presented a completely different map; a pictorial diagram that I think enables Wado students to navigate a more useful and meaningful way of understanding Wado – but a blog post like this is not the place to share this idea; besides, it is still a work in progress, as it should be. [2]

Expanding the map or increasing the resolution?

I think it is too easy to misread what I mean by developing or expanding the map. I don’t think that the Wado map should be seen as a kind of growing, territorial colonialisation, similar to a video game like ‘The Settlers’ or ‘Minecraft’ where from a tiny localised centre you keep occupying new territory and building new structures; that would be like adding extra pages on the end of the syllabus book.

To give a concrete example: Otsuka Sensei was quite content with the idea of nine core solo kata, anything beyond the apex kata of Chinto was classified as ‘extra’. [3]

Paired kata are perhaps another story. If you take them on face value, they are legion! But to focus on their bewildering number is perhaps missing the point.

I speculate that with the paired kata there is a hidden map lurking beneath the seemingly complicated map which features, for example; the ten Kihon Gumite, the thirty-six Kumite Gata, twenty-four Ura no Kumite and all the rest. The clue is when you acknowledge the reality that none of these paired kata contradict the core principles, and it is these core principles that are the real map, the one skulking underneath, and, in content, the ‘Principle Map’ is not such a huge numerical challenge.

The most valuable approach is not necessarily to expand the territory, but to increase the resolution. The territory might well push beyond its boundaries but only in a natural, unforced way, an organic by-product of more defined and focussed examination. The real payback is in the more granular exploration of areas you already think you know.

‘Low-resolution’ has its uses.

Low-resolution thinking is natural to us, it’s the very basic of what we needed to survive and has been with us for tens of thousands of years. But what might have been paramount for hunter-gatherers has now slipped down our list of priorities – I mean who needs to clutter up their thinking about what they might have had for breakfast when they are being chased by a sabre-tooth cat? A boost of adrenalin and the most basic info about an escape route should be enough!

What does ‘increasing the resolution’ mean for your Wado?

Let me start with what it does NOT mean:

- It does not mean knowing more and more about less and less.

- It does not mean you become a slave to detail, which, if taken to its extreme can result in you looking like an obsessive dilettante, all ‘head knowledge’ and no practical/physical skills. [4]

- It does not limit your thinking by allowing you to assume you have it all pinned down. Actually, the reverse should happen; your mind continues to expand.

What it DOES mean is:

- The more granular your understanding the more you appreciate the relationships between the various parts of your Wado map, the underpinning logic.

- This increased resolution enhances your creativity.

- If approached with humility, you begin to realise how little you know, or how things you thought you knew might have been wrong.

How to adopt a ‘granular’ approach to something you thought you knew.

As an example; never, never, never underestimate or dismiss Kihon, I say that because if you take something like the action of Junzuki, this single technique taught at the beginning of your training reveals so much more depth. Why do you think that no matter how many years you have been training you never leave Junzuki behind, you never transcend it? It’s always a work in progress.

But I guess you expected me to say that.

Another example: Take something like the role of ‘Uke’ in paired kata… it took me far too long to realise that Uke is not a mere stooge for the person performing the prescribed technique. Uke has more say in the conversational process and this ‘conversation’ continues all the way to the end of the kata.

The double-edged sword.

I left this part till the end, but it is incredibly important. Essentially, having knowledge in your head is no good on its own. For it to be given any form of concrete real-world potency, the other form of ‘knowledge’ must accompany it; that is the absorption of the technique into your body, to borrow someone else’s rather excellent description; it must be so deeply engrained that it stains your very bones!

Tim Shaw

[1] Yes, we have a syllabus book in Shikukai, and yes it has its uses as an outline, a catalogue of techniques and requirements for grading, but that’s it.

[2] I have been toying with the idea of sharing this type of material through a subscription service like Substack, but I haven’t made my mind up yet.

[3] Notice how the kata Suparinpei dropped off Otsuka Sensei’s map very early on. Also consider Otsuka’s early development of Wado and look at the list of techniques produced for the official registration in the 1930’s; it’s a kind of map, but what was its objective? Who was the map really for?

[4] ‘Dilettante’, I like this much underused word. Definition; ‘A dilettante was a mere lover of art as opposed to one who did it professionally.’

Photo credit: The Settlers screen image courtesy of: https://www.sockscap64.com/games/game/the-settlers-2/

Sample – Part 23, Foreign Parts.

Memories of far-flung locations – have Gi, will travel.

I had always had a longing to travel and explore the world beyond the UK. As evidence for this; during 1981 while I was still wondering what I was going to do in the future and still in Leeds, as a long shot I applied for teaching positions in Tokyo, but with no success. I mention this because I was very flexible in my outlook and prospects and was pretty much prepared to do anything at that time.

Fast forward to later in the year; I sat in a bar in New Orleans chatting with a guy who was on furlough from a Gulf oil rig who told me there was money and travel to be had in the oil industry, though the work was tough. With a wink, he told me that the real adventure and good life was to be found in South America. On the back of that, while I was in Louisiana, I actually went for an interview for a job as an off-shore roustabout on a rig in the Gulf of Mexico. The process stumbled at the last minute when I realised that I needed a Green Card – no Green Card, no job. If that had gone through, any plans I had put in place previously would have just gone out of the window. I suspect that my life would have taken a very different turn if I had gone into the oil business.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

To return to the timeline.

Back in Leeds.

I’d previously hedged my bets by applying to get a Post Graduate teaching qualification. At the time I referred to it as ‘just another string to my bow’, something I could fall back on and dip in and dip out of. But it didn’t quite work out like that.

I got on to the PGCE course in Leeds because I had excellent references and the prospect of a good Honours degree. I also wasn’t quite prepared to abandon my life in Leeds; I had too much invested in it and was reluctant to say goodbye to a city I had loved so much.

But travelling was still on the agenda.

There was a plan that Mark Harland and I were going to do the States in the August of 1981. He and I had travelled abroad together before.

France.

Previously, back in 1979, Mark and I took the boat train to Paris and, once we’d exhausted the capital, we decided we’d explore France. Paris was fun, though I have an abiding sickly memory of trying to shake off the grandmother of all hangovers in the Louvre.

The day we finally chose to leave Paris we had a plan and our logic told us to travel to the furthest end of the Metro system heading for a motorway slip road where we could hitch a lift. But the day we picked was the same day as a rail strike; so, when we got to the slipway ramp we were faced with a queue of about twenty other people all with the same idea. We didn’t help ourselves; we set a target of the town of Chartres; it must have been the A11 as our real target was Le Mans. We wrote the word ‘Chartres’ on a piece of cardboard, but we spelled it wrong!

Against all the odds we got a lift from a young woman in a blue Citroen. At first I couldn’t understand why a woman on her own would pick up two male hitch-hikers, but, whether by accident or design, she gave us the message that she wasn’t the type to be intimidated by two young English guys, this was when she reached forward to where I was sitting in the front and flipped open the glove compartment and there was a revolver just sitting there. Nothing was said, no explanation; I still struggle to make sense of it today.

I mention this because it was on this hitch-hiking adventure that I discovered that Mark and I were compatible travel companions, and, out of this, the American plan was hatched.

However, fate stepped in and the whole project was thrown up in the air (literally) a couple of weeks before we were due to fly out to New York, when Mark rang me and told me he’d had a motorcycle accident and broken his collar bone. I thought about cancelling the trip but the belligerent side of me thought ‘what the hell’ and I went on my own. This went down badly with my then girlfriend as she thought she could ride in on that ticket, but I thought differently. Although she wasn’t happy, later on she typically got her revenge. But that is another story.

New York.

I flew over to New York from London on one of the first no-frills budget airlines, Laker Airways, owned by entrepreneur Sir Freddie Laker. Freddie was actually on the trip himself and went round shaking hands with the passengers. Laker Airways went bankrupt a year later, a victim of the early 80’s recession. The flight was cheap because I bought a ‘standby’ ticket, basically you went on spec.

Apart from the trip to France I’d never travelled abroad before; family holidays were limited to typical UK holiday resorts.

I had relatives in the States and hooked up with a cousin who was married to a Coastguard officer. I stayed some of the time with her and the rest travelling around on my own.

I initially took the Greyhound bus from New York to Buffalo with a brief stop off at Niagara Falls. Then went down the length of the country through Cincinnati and all the way down to Baton Rouge and to New Orleans.

Hitch hiking.

Solo travelling is not without its risks. While travelling I had more than one brush with religious cults who were keen to prey on lone foreign travellers, particularly the Unification Church AKA the Moonies. I didn’t fall for it.

At that time I had a lot of confidence, verging on the reckless and naïve. I had so much belief in my ‘magic thumb’, (the hitch-hiking thumb that did Mark and I so well in France with). I reckoned on using the same technique in the USA.

In the time I was travelling around on my own I chose to stay in the Southern States. I used the Greyhound bus for some journeys; it was cheaper to sleep on an overnight trip on the bus and wake up in a new city, but it was sometimes arctic cold with the intensity of the air-conditioning. I hadn’t packed much in the way of clothing; in fact, I hadn’t packed much at all. I had a shoulder bag, like a two handled Adidas sports bag in which the bulkiest item was my Keikogi. I was living a bit like a tramp.

Generally, the hitch-hiking worked out well for me. I had stitched a Union Jack onto my bag and, while it was useful for the lifts it singled me out too much as a tourist in the cities, it was more useful to just blend in; so, I ended up ripping it off.

I tended to get lifts from pick-up truck drivers, almost always old boys who had been in the military during the war, some asked me if I knew Mrs Brown who lived in Southampton (I guess it was better than asking me if I knew the Queen!). The natural assumption was that the UK was so very small compared to the USA, so everybody knew everybody else.

I had no idea that hitch-hiking was illegal in some states and found this out the hard way.

At some point I fell in with another young guy also hitching. We planted ourselves on the open verge of a rural highway near the Alabama Florida border with our thumbs hanging out. Nobody had been along for a while. I was looking one way up the highway and when I glanced back, he had just vanished into thin air! I later found out that he’d seen what I hadn’t; a cop’s cruiser came up alongside with its lights on. The cop got out, hands on hip (and gun), “Don’t you know that it is illegal in this state to hitch-hike along the highway?”! I reached for the only two cards I had available; I played dumb and I played foreign. When he asked me for ID all I had was my British passport – that did the trick; he let me off with a warning. The guy travelling with me had dived into the ditch, he only reappeared when the cop had gone.

Wado in New Orleans?

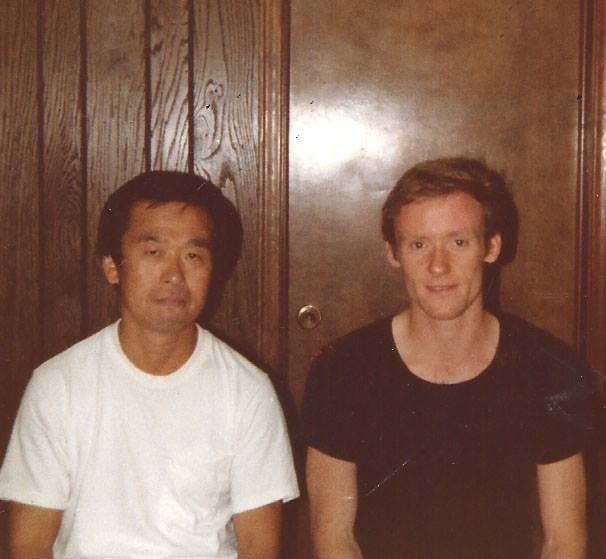

I spent quite a lot of time in New Orleans. Amazingly, by browsing the Yellow Pages I found a Wado Dojo in Metairie New Orleans, and one run by a Japanese Sensei, Takizawa Sensei 6th Dan. This was so rare in the USA; Wado is very much a minority style. If you want Shotokan there are so many karate schools to choose from, one on every street corner, but Wado is as rare as hen’s teeth.

When I met Takizawa Sensei I realised that he was so very different from Suzuki Sensei; very westernised, very… American. Suzuki had been over in New Orleans two years previous. The American’s impression of him was that he was very strict and that he ‘liked a drink’. (When I got back to the UK I spoke to Suzuki Sensei, told him where I had been and that Takizawa Sensei sent his regards; Suzuki was really sniffy about the quality of Wado in New Orleans; he had very high standards).

This was my first experience of Wado outside of the UK. I suppose I expected that standards and practices would be universal… wrong. I had the same experience years later training in Japan. The lesson to learn; don’t make assumptions.

When I turned up in Metairie, despite the fact that they had air-conditioning and the Dojo was so swish and modern, the training was really sedate. They had different ways of performing techniques and their pairs work were limited. They were intrigued by Suzuki’s Ohyo Gumite and Takizawa openly told me he only knew Kihon Gumite one to five and had forgotten the rest (??) He asked me to show them to the Dan grades assembled – I was happy to oblige.

University of New Orleans and a familiar face.

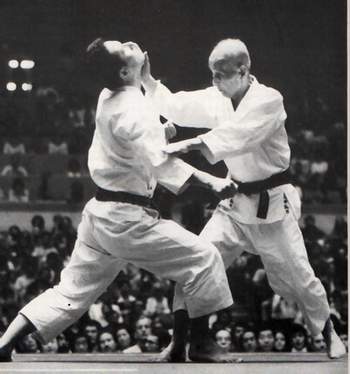

I trained there a few times and also at the downtown YMCA, hosted by Takizawa’s then right-hand man, Larry Hoyle and Dojo instructor Van Robichaux, this was in a handball court. But crucially this contact allowed me access to a unique event at the University of New Orleans; a visit by a team of over forty Japanese Shotokan students hosted by resident Japanese Shotokan Sensei Mikami Takayuki, ex of Hosei University and a contemporary of the famous Kanazawa Hirokazu. There were also some other respected Japanese Sensei there, including a familiar face; Tanaka Masahiko, the same guy on the poster we had over the fireplace at 43 Bexley Grove. A bull neck and a distinctive swagger; he had an injury on his forehead right between his eyes. Later, when we had chance to speak, he said he’d had an accident with a shotgun, where he hadn’t secured the weapon and lost control of the recoil and got whacked between the eyes.

He fought two exhibition bouts. The first against one of the Japanese students, it was a massacre; Tanaka disdainfully brushed aside the timid attacks of the student; he was clearly in awe of the master; then Tanaka chased him with an aggressive run of combinations designed to close the distance, he clearly had a plan, wanting to finish with a bang. And he did; he got close enough to grapple, grabbed his opponent by the lapels put his foot in his stomach and flew backwards and launched him over the top; a perfect Tomoe-nage (stomach throw), he held on to the guy, but the momentum was so powerful that the pair of them, on landing, skidded across the floor, where Tanaka executed the coup de grace.

Tanaka was then put up against one of the best American students, there was some joshing, friendly banter and then the match started. Clearly the American was more than a little intimidated by what he had seen; what followed was a good natured, friendly match, a bit of a come-down from the previous show of superiority. I had the feeling that Tanaka held back for diplomatic reasons. He’d also roughed his own student up… because he could.

Afterwards we all went for a drink at Mikami Sensei’s Dojo. Mikami was avuncular and really chilled, we spoke briefly, he asked me to convey his respects to Suzuki Sensei.

A canvas was laid out over the Dojo floor and what I can only describe as a bathtub full of ice and beer cans was dragged into the Dojo. We certainly needed it after the training at the university, where the air-conditioning was barely working.

Alabama.

It was at this training session that I met Jimmy Lucky and his wife Virginia. Jimmy was a Shotokan teacher from Mobile Alabama, he was so friendly and he gave me his contact details. He said that if ever I was over that way look him up. It just so happened that I was intending to head east along the coast towards Alabama and Florida so I was able to hook up with them for training. I rang them from the bus station in Mobile when I got there and together we all went along to training. This was another first for me; I had never trained with Shotokan students (outside of UNO). But for them, they had never experienced Wado before either.

I remember we did some ‘one step’ sparring; a pre-arranged single attack with a set response; maegeri, which then had to be countered with a gedan barai, gyakuzuki, for me it was all very basic and against the grain. I think they picked up and that and said, “Why don’t you just do what you would do?”, which I did. I used the body evasions that are the bread and butter techniques of Wado; just enough of the turn of the body for their technique to miss by a fraction, executed with a direct counter. They were intrigued and kept asking me to do it again, they had never come across this style of Taisabaki (body management) before. Shotokan had something they called ‘Taisabaki’ but it seemed to involve a big movement off line or a step out of the way before moving back in again to counter. They couldn’t figure it out, they remarked how one moment I was there and then I was gone!

When the training opened out the fun began and I remember some very spirited exchanges.

After training there was a beery night in a nearby bar, where we ordered pitchers of beer (another first) and turkey subs.

Afterwards, as they knew I had nowhere to stay for the night, one of the Dan grades offered me a bed in his spare room. Later on I found out that he was originally from Liverpool. As I went to bed, he told me that by the time I get up he’d have gone to work; there was plenty for breakfast in the icebox and to slam the door on my way out. Very trusting, I never saw him again.

More adventures in the southern states.

I travelled around that southern edge for a while, sometimes hitching, sometimes on the Greyhound, often sleeping on the bus, at times paying for a room in a cheap motel, I needed the shower I was beginning to smell like a tramp. I had plans for a fuller exploration of Florida but the arrival at a place called Panama City put me off entirely. I ended up in the wrong side of town, on a Sunday, luckily there was nobody around. I fell in with a bunch of old guys, derelicts; I remember sitting with them underneath a pier, a kind of jetty, drinking whiskey out of a bottle passed around in a brown paper bag. They warned me that it would be in my best interests to make my way back to the bus station (bus stations always seemed to be near the seedier parts of town, that was why I ended up where I did).

After that experience I decided to head up into Georgia, overnight. I witnessed some of the most spectacular thunderstorms I had ever seen.

I remember being entertained on the bus by a kid who can’t have been more than eight years old; his dad and the other passengers encouraged him to give full voice to the Kenny Rogers song ‘Lucille’, he knew most of the verses but really let rip on the chorus, “You picked a fine time to leave me Lucille, with four hungry children and a crop in the field…”, everyone clapped and grinned.

I spent a little time bumming round Atlanta and then went as far up as St. Louis, Missouri. I met some colourful people, including a guy who told me he was a hitman for the CIA…yeah.

But I eventually had enough of wandering and returned to New Orleans. To round it all off I travelled across to Houston, Texas, from where I flew back to the UK.

I don’t think I really got the best out of the trip. I had no trouble being on my own, but I think Mark and I together would have really been able to push the boat out.

I came back to Leeds sun-browned from so much time on the open road and invigorated. The experience gave me a boost, I knew more about the wider world.

In some ways it was a bit of a bump coming back to Leeds. I was about to start a new course but we’d let Bexley Grove go; Mark, Steve and Chris had all left. I bit the bullet and, only out of convenience, I returned to halls of residence.

I was temporarily billeted in one of the halls tucked at the back at Beckett Park, this time in the Big House on the Hill, Carnegie Hall, with all the PE students. And, I had to deal with the blow-back from my girlfriend.

Tim Shaw

Image at the top of this post; myself at the University of New Orleans (far right, Jimmy Lucky).

Shikukai – Fresh initiatives. New Approaches to Fight Training.

Emerging from the various lock-downs and phased restrictions, what we were really missing were opportunities for sparring, the full range, from drills to Jiyu Kumite. After all, this was what we’d all been brought up on, and, for nearly two years Covid had denied us the chances for free-engagement.

Junior grades, who may have started before or even during the pandemic, had very little opportunity to experience how their techniques would fare in an unrehearsed exchange of punches and kicks.

For many of us this aspect of our training has been sorely missed, and its absence made us realise how much we’d taken it for granted.

Focussing on the positive.

However, there are signs that we may be able to leave this negativity behind us and start to emerge into the daylight.

Within Shikukai, instructors have been galvanised into action with two fresh initiatives specifically related to kumite training, developed independently and born out of the fermentation time forced on us by Covid.

The Shikukai team of instructors refused to allow training to be put into suspended animation during the various lock-downs and isolations and instead crafted new ways of continuing training (e.g. Zoom) which brought about fresh ways of looking at what we do. Which, incidentally, also fed into our current restructuring and modernising initiative within Shikukai as a whole.

Fresh ideas.

The two initiatives are up and running; one in the South West, devised by Steve and Pam Rawson, and the other in Essex, piloted by Steve Thain.

These two projects are refreshingly different in approach, which to my mind underlines the diversity available in this aspect of training. Fight training supplies opportunities for some really creative thinking; a contrast to syllabus work and the focus on minutiae associated with high technical demands.

Weymouth.

Steve and Pam’s ideas sprang out of their focussed Zoom sessions geared towards fighting drills – a regular weekly event over the last few months. It was almost inevitable that they would want to transfer this into live, face-to-face training, and an opportunity opened up in Weymouth.

A new business appeared in the town centre called ‘The Combat Lab’, a multi-disciplinary martial arts initiative/business project. Steve and Pam approached the owner and arranged dates and times for their proposed workshops, the first of which occurred in January 2022.

They planned to take full advantage of the space and the facilities. The workshop was designed with the use of equipment (bags etc.) in mind. Training was thoughtfully constructed and featured a broad range of fighting skills, including drills and take-downs.

For this first workshop Ken Bu Jyuku students were well supported by Shikukai members from Exmouth and Chippenham. With a new date set for March and a revised format creating separate space and time for women only training, followed by men’s training. Places are limited, so contact Steve and Pam if you are interested (Full details on the main Shikukai website).

Essex.

The project in Essex took on a different form. The springboard for this came from Steve Thain’s initiative to organise ‘Pop-Up’ workshops during gaps in pandemic restrictions. Although these were not exclusively focussed on fighting, they were designed to explore free-form movement. For Steve the inevitable next step was to design ‘fight-based’ versions of the same Pop-Up model.

His approach was to trawl all of the go-to fight training methods developed over the years. He drew up a list of twenty numbered practices.

The lowest numbers related to the most accessible methods; ones suitable for lower graded, least experienced students; while the higher numbers required significantly more skill and experience. Students were then given the choice of which level to work at. This instantly reduced any trepidation the least experienced may have felt.

The modes of fight training included such things as; mirroring, shoulder tapping, one attack one defends, Shiai, Ohyo Henka Dosa, and fifteen others too difficult to explain in a brief blog post.

Having participated in two of these workshops (the last being Feb. 1st) although, by its nature as a ‘pop-up’ it is only for one hour, it’s very intense and hugely enjoyable, whatever level you are at.

The next one takes place in March (date to be confirmed).

Tim Shaw

Shizentai.

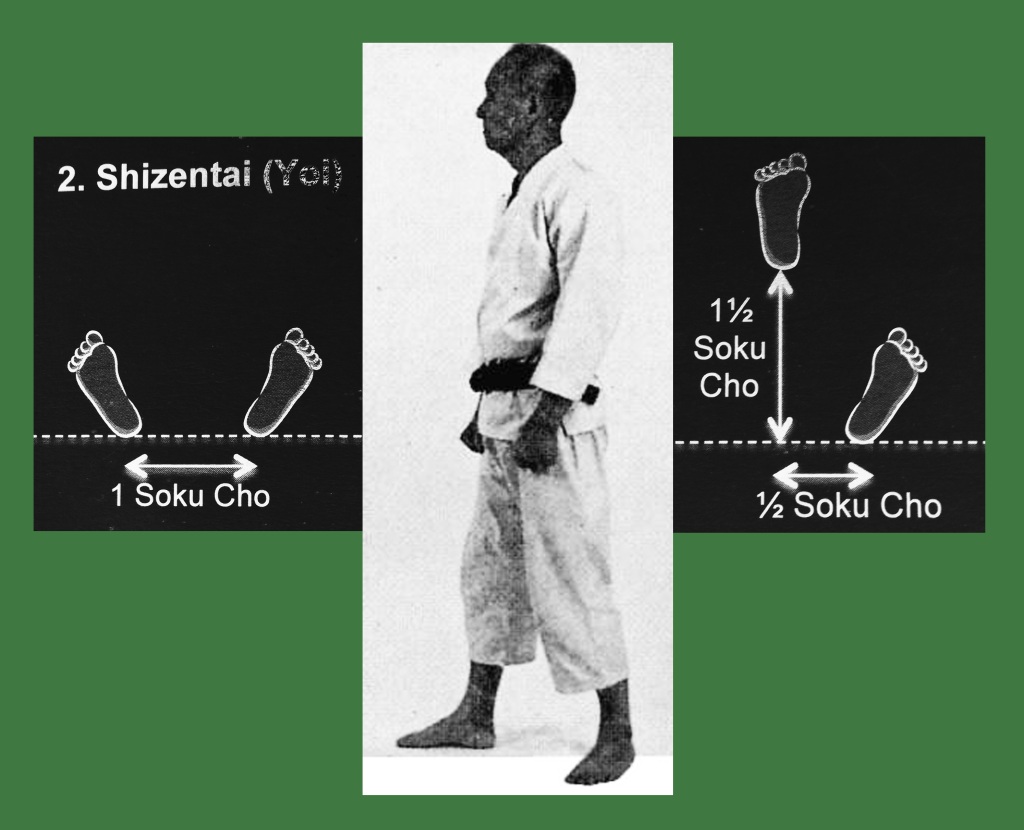

Look through most Wado syllabus books and a few text books and you are bound to see a list of stances used in Wado karate; usually with a helpful diagram showing the foot positions.

One of the most basic positions is Shizentai; a seemingly benign ‘ready’ position with the feet apart and hands hanging naturally, but in fists. It is referred to as ‘natural stance’, mostly out of convenience; but as most of us are aware, the ‘tai’ part, usually indicated ‘body’, so ‘natural body’ would be a more accurate fit. [1].

In this particular post I want to explore Shizentai beyond the idea of it being a mere foot position, or something that signifies ‘ready’ (‘yoi’). There are more dimensions to this than meets the eye.

Let me split this into two factors:

- Firstly, the very practical, physical/martial manifestation and operational aspects.

- Secondly, the philosophical dimension. Shizentai as an aspiration, or a state of Mind.

Practicalities.

The physical manifestation of Shizentai as a stance, posture or attitude seems to suggest a kind of neutrality; this is misleading, because neutrality implies inertia, or being fixed in a kind of no-man’s land. The posture may seem to indicate that the person is switched off, or, at worst, an embodiment of indecisiveness.

No, instead, I would suggest that this ‘neutrality’ is the void out of which all possibilities spring. It is the conduit for all potential action.

Isn’t it interesting that in Wado any obvious tensing to set up Shizentai/Yoi is frowned upon; whereas other styles seem to insist upon a form of clenching and deliberate and very visual energising, particularly of the arms? As Wado observers, if we ever see that happening our inevitable knee-jerk is to say, ‘this is not Wado’, or at least that is my instinct, others may disagree.

Similarly, in the Wado Shizentai; the face gives nothing away, the breathing is calm and natural, nothing is forced.

In addition, I would say that in striking a pose, an attitude, a posture, you are transmitting information to your opponent. But there is a flip-side to this – the attitude or posture you take can also deny the opponent valuable information. You can unsettle your opponent and mentally destabilise him (kuzushi at the mental level, before any physical contact has happened). [2]

Shizentai as a Natural State – the philosophical dimension.

I mentioned above that Shizentai, the natural body goes beyond the corporeal and becomes a high-level aspiration; something we practice and aim to achieve, even though our accumulated habits are always there to trip us up.

In the West we seem to be very hung up on the duality of Mind and Body; but Japanese thinking is much more flexible and often sees the Mind/Body as a single entity, which helps to support the idea that Shizentai is a full-on holistic state, not something segmented and shoved into categories for convenience.

This helps us to understand Shizentai as a ‘Natural State’ rather than just a ‘Natural Body(stance)’.

But what is this naturalness that we should be reaching for?

Sometimes, to pin a term down, it is useful to examine what it is not, what its opposite is. The opposite of this natural state at a human level is something that is ‘artificial’, ‘forced’, ‘affected’, or ‘disingenuous’. To be in a pure Natural State means to be true to your nature; this doesn’t mean just ‘being you’, because, in some ways we are made up of all our accumulated experiences and the consequences of our past actions, both good and bad. Instead, this is another aspect of self-perfection, a stripping away of the unnecessary add-ons and returning to your true, original nature; the type of aspiration that would chime with the objectives of the Taoists, Buddhists and Neo-Confucians.

Although at this point and to give a balanced picture I think it only fair to say that Natural Action also includes the option for inaction. Sometimes the most appropriate and natural thing is to do nothing. [3]

Naturalness as it appears in other systems.

In the early days of the formation of Judo the Japanese pioneers were really keen to hold on to their philosophical principles, which clearly originated in their antecedent systems, the Koryu. Shizentai was a key part of their practical and ethical base. [4] In Judo, at a practical level, Shizentai was the axial position from which all postures, opportunities and techniques emanated. Naturalness was a prerequisite of a kind of formless flow, a poetic and pure spontaneity that was essential for Judo at its highest level.

Within Wado?

When gathering my thought for this post I was reminded of the words of a particular Japanese Wado Sensei. It must have been about 1977 when he told us that at a grading or competition he could tell the quality and skill level of the student by the way they walked on to the performance area, before they even made a move. Now, I don’t think he was talking about the exaggerated formalised striding out you see with modern kata competitors, which again, is the complete opposite of ‘natural’ and is obviously something borrowed from gymnastics. I think what he was referring to was the micro-clues that are the product of a natural and unforced confidence and composure. For him the student’s ability just shone through, even before a punch was thrown or an active stance was taken.

This had me reflecting on the performances of the first and second grandmasters of Wado, particularly in paired kata. On film, what is noticeable is their apparent casualness when facing an opponent. Although both were filmed in their senior years, they each displayed a natural and calm composure with no need for drama. This is particularly noticeable in Tanto Dori (knife defence), where, by necessity, and, as if to emphasise the point, the hands are dropped, which for me belies the very essence of Shizentai. There is no need to turn the volume up to eleven, no stamping of the feet or huffing and puffing; certainly, it is not a crowd pleaser… it just is, as it is.

As a final thought, I would say to those who think that Shizentai has no guard. At the highest level, there is no guard, because everything is ‘guard’.

Tim Shaw

[1] The stance is sometimes called, ‘hachijidachi’, or ‘figure eight stance’, because the shape of the feet position suggests the Japanese character for the number eight, 八.

[2] Japanese swordsmanship has this woven into the practice. At its simplest form the posture can set up a kill zone, which may of may not entice the opponent into it – the problem is his, if he is forced to engage. Or even the posture can hide vital pieces of information, like the length or nature of the weapon he is about to face, making it incredibly difficult to take the correct distance; which may have potentially fatal consequences.

[3] The Chinese philosopher Mencius (372 BCE – 289 BCE) told this story, “Among the people of the state of Song there was one who, concerned lest his grain not grow, pulled on it. Wearily, he returned home, and said to his family, ‘Today I am worn out. I helped the grain to grow.’ His son rushed out and looked at it. The grain was withered”. In the farmer’s enthusiasm to enhance the growth of his crops he went beyond the bounds of Nature. Clearly his best course of action was to do nothing.

[4] See the writings of Koizumi Gunji, particularly, ‘My study of Judo: The principles and the technical fundamentals’ (1960).

Event Report – 26th July 2021

Report by Natalie Harvey (3rd Dan)

26th July 2021 – 2 hours

Led by Steve Thain (4th Dan)

Theme – Ohyo Henka Dousa* (OHD)

Objective – To develop center, energy, connection, flow and sensitivity whilst steadily building towards real fighting utilising the Wado techniques and application you are trying to master.

After some planning we put into action and launched our first pop up course. The concept was a simple one. Design a session with the freedom to work on an aspect of Wado that you really wanted to get into. There is no instructor, everyone trains, small groups, but the session is planned and led by one person. Our first course was planned and led by Steve Thain (4th Dan).

Steve created a methodical structure that built up over two hours. During the session our small group of six immersed ourselves in the practice and development of OHD, and supporting practices. We focused on the awareness of Wado principles, connecting to our centre, body centric movement allowing energy to flow freely within and beyond. Complete awareness of where we are in relation to our external world, and within ourselves internally. When trying to explain how someone should feel during OHD it is almost impossible to nail one way. Relaxed, but not all the time, be strong, but not all the time, use power and tension, but not all the time. I believe that it is all these things so long as you are self aware. If you are carrying unnecessary tension in your body, it will definitely show within this practice. I find myself continuously scanning for tension, my breath, stability on my feet and shifting position from kiru within.

When we connect to a partner in OHD and feel their pressure, depending on how in tune they are to their body, their intent will be felt. Ideally the flow which appears to initiate from them will transfer into the other person into what Wado Practitioners would recognise to be Ten-I, and we essentially become one. Within the cycle of OHD there is no beginning nor end. We shift between Ten-Ei, to Ten-Ei, to Ten-Ei. As the practice develops we may find ourselves naturally shifting and flowing from some or all three Ten-Ei to Ten-Tai to ten-Gi.

The other aspect that I took away from the session was ‘Being in the moment’ and not planning ahead. As soon as it had been pointed out to me, I realised that my mind had disconnected to my own body which meant I had disconnected to the other person’s centre and essentially I was doing my own thing, badly. I think in Japanese the term Mushin (a non-reflective, but mindful state), might be a good term for this explanation. When I brought my attention back to the moment, the chaotic feeling of the interactions with my partner seemed to go. Time felt as though it had slowed enough for me to engage meaningfully.

You don’t often get the opportunity to really get into something you love to do with like minded people chasing a common, personal and group goal . Two hours is never enough, but this is just the first Pop up of many we have planned with various theme focuses. My gut says these focused sessions will elevate all participants’ ability at an expressed rate compared to the regular training format. The regular dojo time is vital to our learning and we continue to attend regular Instructor led sessions in the usual dojo. Time will tell. For now we are enjoying the journey and have already booked our second pop up mini course for September 2021!

*Ohyo Henka Dousa

応用変化動作 (ohyo henka dousa)

“Applying (Practice) the variation of movements (Henkawaza) relating to the opposition’s initiations.”.

Wado on Film (Anything on film!) – Part 2.

Continued from part 1. What can we possibly gain from these ‘records’ of genius? How do we read the evidence presented to us?

What are we able to judge?

To return to the martial arts (and other arts).

Observing films on YouTube or other sources; shapes and patterns can only give us so much. It’s how we process the information that counts, but usually we cannot help but to attach our own baggage to it; this can cause its own problems.

To expand: If we look at the idea of works of art; it is said that it’s all about relationships:

- The relationship of the artist to their subject – think of landscapes or portraits. The artist must engage and interpret their personalised understanding of the subject.

- The relationship of the artist to their medium – this is the practical depiction of the theme and all of the technical aspects involved. This is the means by which the message is delivered.

- The relationship with the artist through their work to their audience.

Now, extend that to master Otsuka, (whether it is on film or a demonstration in front of an audience):

- His subject is his understanding of Japanese Budo.

- His medium is his performance – what he chooses to show is through the prism of his selected material, be that solo or paired kata or fundamentals.

- Then, ultimately, the connection/relationship between the ‘artefact’ as presented, and the viewer, the audience.

As with all of the above, clearly, the viewer has to be up to the task.

For a viewer in an art gallery, a Joshua Reynolds portrait from 1770 may present less of an intellectual challenge than a Jackson Pollock ‘Action Painting’ from 1948. The crisp clarity of Reynolds gives the viewer more to grasp on to than the mad, seemingly random, spatter of paint that Pollock applied to his canvases. But both have amazing value and depth (to my mind anyway).

It has been said to me on more than one occasion that those demonstrations that master Otsuka did in his later life were actually designed with a particular audience in mind; for the real aficionados, for those who really had the eyes to see what we mere mortals fail to see. They are not quite Jackson Pollock, this is perhaps where the metaphor is a little too far stretched, but sadly they still reside in an area above most of our pay grades.

To understand Otsuka (or Pollock) we would need to have considerable insight into the workings of the artist’s world combined with the ability to grasp the intangible.

With master Otsuka a good starting point would be to understand the world in which he lived, as well being prepared to ditch our western lenses, or at least be aware of how they colour our understanding of Japanese society and culture at that particular time. But even then, if we plunged headlong into that task, it would need to be supported by a huge amount of practical knowledge of Japanese Budo mechanics relevant to that particular stage in its development. You would be hard pressed to find anyone with those credentials.

The comparison with the visual artists and master Otsuka can also be exercised in this way: It is a sad fact that when we encounter an artist’s work in a gallery it is often in isolation; we seldom see the work as part of a continuum, instead it is a snapshot of their development at the particular time it was produced. There are very few examples in the art world where this development can be seen; the only one I can think of is the wonderful Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where it used to be possible to follow the artist’s development as a timeline; Van Gogh’s immature work looks clunky and uncultured, he’s finding his feet, he experiments with different styles (Japanese prints influenced, pointillism, etc) and then his work starts to blossom as it becomes more emotionally charged. What a pity he only worked for about ten years. My guess is that given more time he would have gone pure abstract, what a development that would have been!

What if?

To return to Nijinsky (from part 1) – what if a piece of film was discovered of Nijinsky dancing? What would a modern ballet dancer be able to gain; how would they judge it? Perhaps Nijinsky’s famous ‘gravity defying’ leaps would not look so impressive, in fact, compared to contemporary dancers he might look very ordinary. We will never know.

(Perhaps someone might comment that he has his hand out of position, or that he is looking in the wrong direction?)

But maybe the real power is in the myth of Nijinsky as another form of truth, which allows Nijinsky to become an inspiration, a talisman for modern dancers. [1]

For master Otsuka, as suggested above, the pity would be that his whole reputation and legacy should hang on hastily made judgements of those movies shot in later life.

But who knows; if he did have film of him performing when he was in his early 40’s (say from the mid 1930’s) perhaps he would have hated to have been judged by his movements and technique at that age? I would suggest that early 40’s would have put him at his physical prime, but not necessarily at his technical prime.

It’s a bit like the way great painters would hate to be judged by their early work. [2].

Like anything that is meant to be in a state of continual evolution, its early incarnations probably served some uses, however crude, but it’s never wise to stick around. Creatives like Otsuka weren’t going to allow the grass to grow under their feet. [3]

Anecdotes of Otsuka’s early days told by those close to him inform us that his fertile creativity was a restless reality; his mind was constantly in the Dojo. The truth of this comes from his insistence that Wado was not a finished entity, how can it ever be?

Conclusion.

I’m not saying that it is a completely pointless exercise. In writing this I am still working it out in my own head, trying to remind myself that we are still fortunate to have some form of connection to Otsuka Sensei, however tenuous, and how lucky we are to still have people around who bore witness to the great teacher, although, as we know, that will slip away from us so gradually that we will hardly notice it.

I have to remind myself that we are supposed to be part of a living tradition, a continuing stream of consciousness; a true embodiment of the physical form of what Richard Dawkins called a ‘meme’ [4]. This is why instructors take their responsibilities so seriously to ensure that Wado remains a ‘living tradition’, with emphasis on the ‘living’, not an empty husk of something that ‘used to be’. This is why I am reluctant to describe master Otsuka’s image as an ‘anchor’, because an anchor, by its very nature, impedes progress.

The best we can hope for from these ghostly moving pictures from the past is that they can be seen as some kind of inspirational touchstone. But, like the shadows in Plato’s Cave it would be a mistake to take them for the real thing [5].

Tim Shaw

[1] For anyone interested in Vaslav Nijinsky I recommend Lucy Moore’s book, ‘Nijinsky’. It tells an amazing story of an amazing man in an amazing age. Why nobody has made a movie about Diaghilev, the Ballets Russes and Nijinsky I will never know. I reckon Baz Luhrmann would do a fine job if he was ever let loose on the project.

[2] I have to acknowledge that in most competitive sporting fields the athlete is probably at his/her overall prime in their more youthful days. But, when looked at in the round, karate and other forms of Japanese Budo run to a different agenda. For me, and many others, sport karate is not the end product of what we do – it’s a by-product, an additional bonus for those who choose that path.

Look at the careers of dancers. I heard it said that dancers die twice. The first time happens when by injury or by more gradual natural debilitation they have to stop doing the one thing they love, thrive on and that their whole identity has been wrapped up in. The second time, is obvious. As this BBC article (and link to radio documentary) explains: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/1fkwdll6ZscvQtHMz4HCYYr/why-do-dancers-die-twice

[3] I know that am rather too fond of making references to jazz musician Miles Davis, but I have a memory of reports of Miles refusing to play music from his iconic ‘Kind of Blue’ album in his later years; he would say, ‘Man, those days are gone’ underlining his forever onwards trajectory – just as it should be.

[4] ‘Meme’ NOT the Internet’s interpretation of the word but, like a gene. However, instead of being biological, it refers to traditions passed down through cultural ideas, practices and symbols. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meme

[5] ‘Plato’s Cave’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allegory_of_the_cave

Otsuka picture source: http://www.dojoupdate.com/wado-ryu-karate/master-hironori-otsuka/

Wado on Film (Anything on film!) – Part 1.

On the surface it would appear that we are blessed to have so much film of the founder of Wado Ryu available to us. It is lucky that Otsuka Hironori was not camera shy and showed enough foresight to actually have himself recorded with the intention of securing the legacy of his techniques and ideas for future generations. I have heard that there is even more unseen material that has been archived away, held secure by his inheritors.

Although it is interesting that there seem to be zero examples of film of Otsuka Sensei as a younger man; while there are photographs a plenty. (Otsuka Sensei was born in 1892 and only passed away in 1982).

He appeared to hit his filmic stride in his mid-seventies. Although a while back, a tiny snippet of footage of the younger Otsuka did appear as almost an afterthought on a JKA Shotokan film. It was a bare couple of seconds, it certainly looked like him – he was demonstrating at some huge martial arts event in Japan; the year is uncertain, but I am guessing some time in the 1950’s. In this film there was an agility and celerity to his movements which is not so evident in his later years. [1]

Historically, it does seem odd that there is so little film available from those years of such a celebrated martial artist.

Ueshiba Morihei, the founder of Aikido has a film legacy that goes back to a significant and detailed movie shot in 1935 at the behest of the Asahi News company. Ueshiba was then a powerful 51-year-old, springing around like a human dynamo, it’s worth watching. [LINK]

On first viewing that particular film it left me scratching my head; initial examination told me that the techniques looked so fake. But the more I watched, there were individual moments where some strange things seemed to happen (at one point his Uke is propelled backwards like an electric shock had gone through him). At times Uke seems to attempt to second-guess him and finds himself spiralling almost out of control. Really interesting.

But for Wado, is this even important? Why does it matter? Afterall, Wado Ryu had already been launched across the world, much of which happened during Otsuka Sensei’s lifetime. Also, the first and second generation instructors were doing the best of a difficult job to channel Otsuka Sensei’s ideas.

So, what can we gain from watching flickering images of master Otsuka showing us the formalised kata or kihon? What value does it have?

I saw Otsuka Sensei in person in 1975. I watched in awe his demonstration on the floor of the National Sports Centre, Crystal Palace in London. I was only seventeen years old. I remember thinking at the time, ‘here is something very special going on in front of my eyes – I know that – but I can’t put my finger on exactly what it is’.

At that age and the particular stage of my development, I had very little to bring to the experience. I lacked the tools. Possibly the only advantage I had at that time was I was carrying no baggage, no preconceptions; maybe that is why the memory has stayed so clear in my mind [2].

Interestingly, Aikido founder master Ueshiba’s own students, in later interviews lamented that they wished they’d paid more attention to exactly what he was doing when he was demonstrating in front of them; even when he laid hands upon them, they still struggled to get it.

Can we ever hope to bridge the gap?

I think it is useful to acknowledge the problem. The reality is that we are THERE but NOT THERE; we are SEEING but not SEEING. I believe that we often lack the refined tools to understand what is really going on and what is really useful to us as developing martial artists. It comes down in part to that old ‘subjectivity’ versus ‘objectivity’ problem; can we ever be truly objective?

But it is the evanescence of the experience; it flickers and then it is gone and all we are left with is a vain attempt to grasp vapour. But isn’t that the essence of everything we do as martial artists?

To explain:

Two forms of artefact.

I read recently that in Japanese cultural circles they acknowledge that there are two forms of artefact; ones with permanence, solidity and material substance, and ones with no material substance, but both of equal value.

The first would include paintings, prints, ceramics and the creations of the iconic swordsmiths. For example, you can actually touch, hold, weigh, admire a 200 year old Mino ware ceramic bowl, or a blade made by Masamune in the early 14th century – if you are lucky enough. These are real objects made to last and to be a reflection of the artist’s search for perfection; they live on beyond the lifetime of their creator.

But the second, only loosely qualifies as an artefact as it has no material substance, or if it does it has a substance that is fleeting. This is part of the Japanese ‘Way of Art’ Geido.

There are many examples of this but the best ones are probably the Tea Ceremony (Sado) and Japanese Flower Arranging (Kado). Even the art of Japanese traditional theatre which is so culturally iconic actually leaves no lasting material artefact.

In the Tea Ceremony the art is in the process and the experience. Beloved of its practitioners is the phrase, ‘Ichi go, Ichi e’ which means ‘[this] one time, one place’.

The martial arts also leave no material permanence behind. Their longevity and survival are based upon their continued tradition (this is the meaning of ‘Ryu’ as a ‘stream’ or ‘tradition’, it seems to work better than ‘school’). The tradition manifests itself through the practitioners and their level of mastery; this is why transmission is so important. But a word of caution; the best traditions survive not in a state of atrophy, but as an evolving improving entity. It is all so very Darwinian. Species that fail to adapt to a changing environment and just keep chugging on and doing what they always do soon become extinct species.

Film (Nijinky, a case history).

Vaslav Nijinsky (1890 – 1950) was the greatest male ballet dancer of the 20th century. He was probably at his majestic peak around about 1912 as part of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. To his contemporaries Nijinsky was a God; he could do things other male dancers could only dream of; he danced on pointe and his leaps almost seemed to defy gravity. As this quote from the time tells us:

“An electric shock passed through the entire audience. Intoxicated, entranced, gasping for breath, we followed this superhuman being… the power, the featherweight lightness, the steel-like strength, the suppleness of his movements…”.

But, there was never any film made of this amazing dancer, so, all we have left are these words. Even though, at the time, movie-making was on the rise (D. W. Griffith was knocking out multiple movies in the USA in 1912 and earlier). At the time the dance establishment distrusted the new medium of moving pictures, they feared that it trivialised their art and turned it into a mere novelty; which clearly proved to be incredibly short-sighted.

If Nijinsky, arch-performer, had anything to teach the world of dance it is lost to us. Incidentally it is said that Nijinsky destroyed his mind through the discipline of his body. He ended his days in and out of asylums and mental hospitals.

We will never know how good Nijinsky was in comparison to modern dancers, or if it was all a big fuss about nothing. But then again, the very same could be said about any famous performer, sportsperson or martial artist born before the invention of moving pictures.

Other forms of recollections or records that act as witnesses.

A writer or composer leaves behind another form of record. For composers before the first sound recordings in 1860 it was in the form of published written music or score. We would assume that this would be enough to contain the genius of past musicians?

But maybe not.

Starting right at the very apex of musical genius, what about Mozart?

Well, maybe those written symphonies, operas etc. were not a faithful reflection of the great man? Certainly, there is some dispute about this. There has been a suggestion that rather like the plays of Shakespeare, all we have left are stage directions, (with Shakespeare the actors slotted in whatever words they thought were appropriate!).