teaching

Humbled Daily.

Before I launch into this latest blog theme, just a quick word about a new development.

I wanted to extend this writing project into something bigger and so have set up on Substack, a subscription service which is really taking off. I will write a following blog post to outline my plans, but basically it is already up and running. Please support this new project. It can be found at: https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

On with the theme…

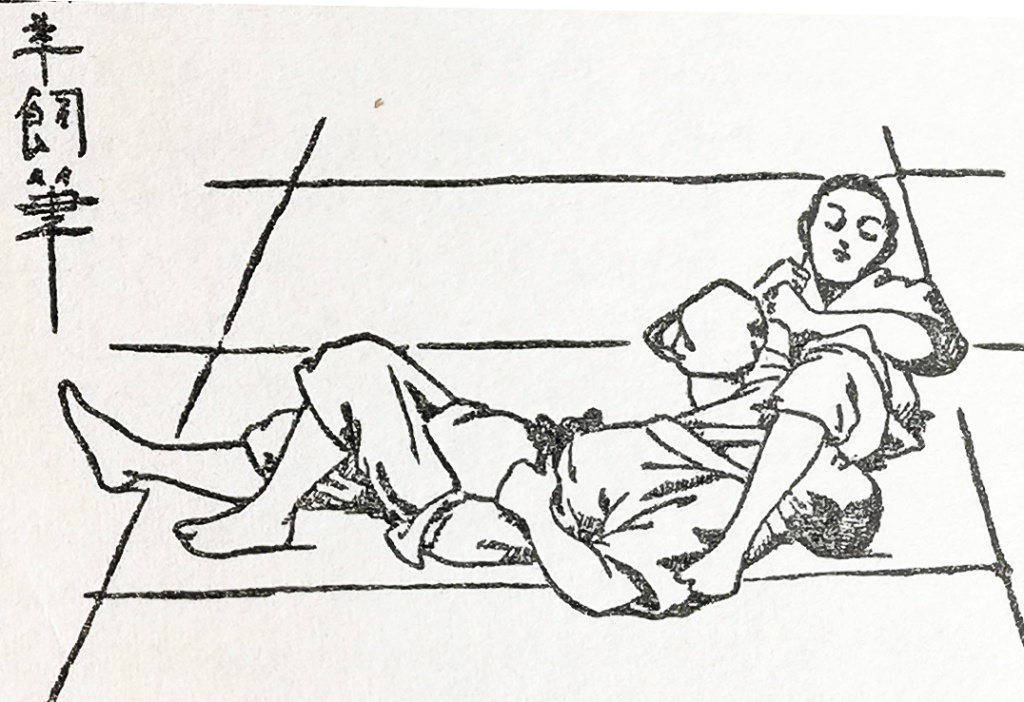

In a recent interview with movement guru Ido Portal he mentioned that grapplers and wrestlers get humbled daily, and it was a healthy thing. They roll on the mat with people of different abilities and frequently experience the challenges that such opportunities present. Often, they fail in their intentions; frequently someone else’s intentions win over theirs and they experience failure. In fact, an intense session may well involve a rolling series of mini-victories and mini-defeats. These are all valuable growth experiences. [1]

Portal says that this seldom happens in traditional martial arts, and he’s right. While not being entirely absent, it certainly doesn’t happen to that intensity.

In traditional martial arts very often the training scenario is so tightly directed that there is little space for this type of training; or, in some cases ‘loss’ is too high a price to pay that it is actually demonised, or only seen for its negative attributes.

What are the real obstacles for us as traditional martial artists to engage in parallel ‘humbling’ interchanges? Here is a list of the potential problems:

- Attitude, this might be related to ego, rank, status etc. I find it ironic that ‘humility’ in Budo is seen as a positive attribute, yet the aforementioned attitude problems are allowed space in the Dojo.

- Avoidance. We know the phrase ‘risk averse’, if you don’t willingly embrace challenge it’s going to be very difficult to improve. [2]

- The constrictions of the training format. We know that our training in traditional martial arts is limited by having to fit so much into a limited time; our priority has to be the syllabus as this is the framework upon which everything depends. How to overcome these limitations often falls on the creativity of the Sensei. Some are good at this, others not so.

- The absence of ‘Play’. Often derided, but, if we think about it, some of our most powerful learning experiences have come to us through play – we only have to think of the physical challenges of our childhood.

And what about competition and sport?

The demonisation of ‘loss’ is perhaps amplified when martial arts become sports. Although, today there is a trend where everybody has to be a winner, it’s an illogical formula. I will counter this with the pro-hierarchy viewpoint. If there is no ladder-like hierarchy to climb then there is no value system. When everything becomes the same worth there’s nothing to aspire to, no striving, no reaching, the whole enterprise becomes meaningless.

In a karate competition the winner’s position becomes of value because of everyone who pitched in and competed on that day. The winner should feel genuine gratitude towards all of those who competed against him or her, it was their efforts that elevated the champion to that top position. And, although all of those people don’t get the trophy or the accolades, they gain so much in the experience of just competing. This is the true ‘everybody is a winner’ approach.

In a healthy Dojo environment instructors are beholden to devise ever more creative ways of training to allow students to experience lots of free-flowing exchanges, where mistakes are seen as learning experiences. A while back, I shamelessly stole a phrase from an ex-training buddy who was from another system. He called this stuff ‘flight time’, as in, how trainee pilots clock up their hours of developing experience. If you get the balance right nothing is wasted in well designed ‘flight time’ in the Dojo. Over the last ten years or so I have been working on different methods of creating condensed ‘flight time’ experiences. When it’s going well there are continually unfolding successes and failures, and the best part of it is that during training everybody gets it wrong sometimes and therefore has to learn to savour the taste of Humble Pie.

Bon Appetit.

Tim Shaw

[1] I have heard similar things from the early days of Kodokan Judo, hours and hours of rolling and scrambling with opponent after opponent.

[2] ‘Invest in loss’ is a phrase often heard among Tai Chi people. It describes the lessons learned from failure. The late Reg Kear told a story about his experiences with the first grandmaster of Wado Ryu, who said something similar to, ‘when thrown to the floor, pick up change’ and then, with a smile, mimed biting into a coin.

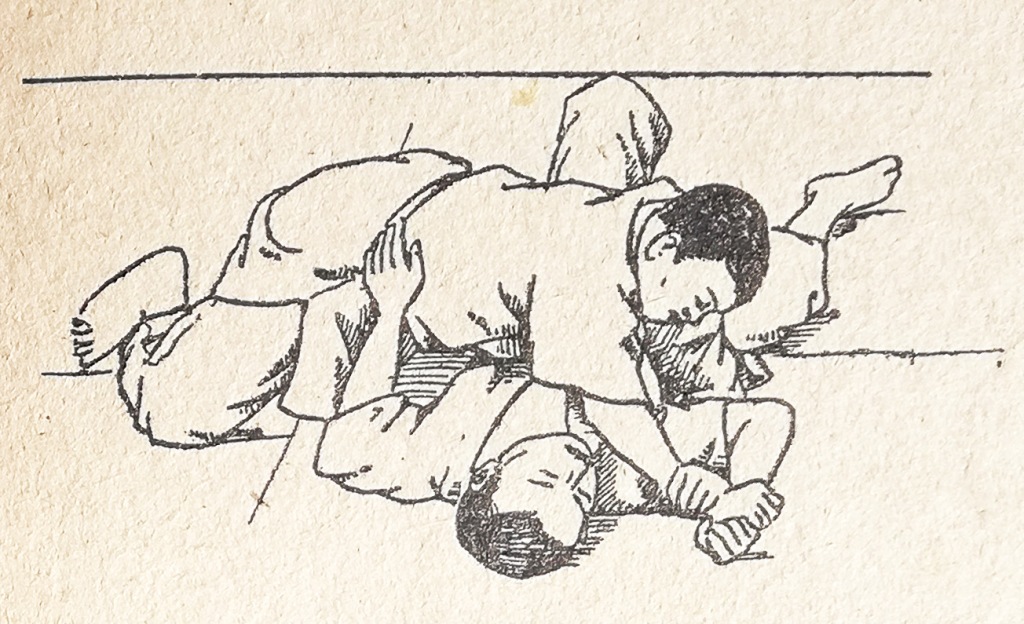

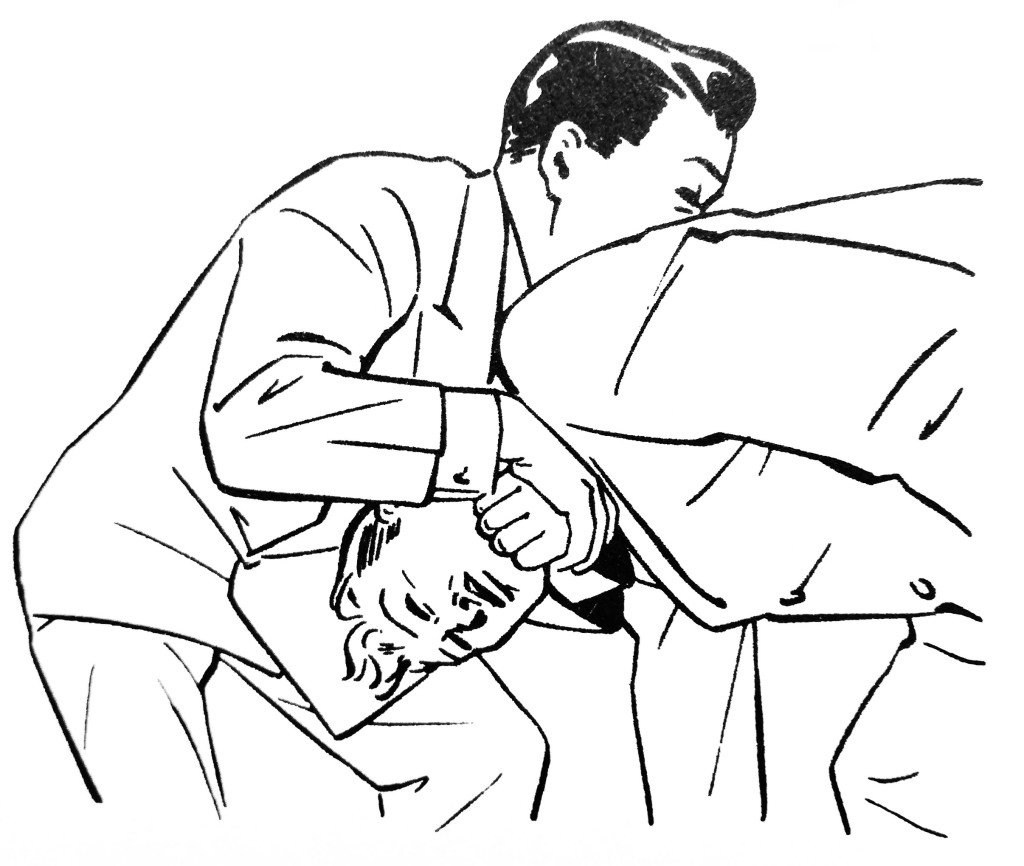

Featured images from ‘The Manual of Judo’, E. J. Harrison 1952.

Book Review – ‘The Way of Judo, a Portrait of Jigoro Kano and his Students’ John Stevens.

A biography of the founder of Judo and what his life tells us about Japanese martial arts and modernisation.

You might ask what a book about the originator of Japanese Judo is doing appearing on a blog about Wado karate? To explain this, I don’t think it’s too bold a statement to say that Kano Jigoro was instrumental in creating the martial arts eco-culture that the founder of Wado Ryu, Otsuka Hironori, was brought up in. Kano was a moderniser and an iconoclast and so was Otsuka, although Kano was senior to Otsuka by nearly thirty years. Otsuka may have known of Kano but I doubt there was any close connection (Kano died in 1938, the same year that Otsuka founded Wado Ryu as a separate entity – Otsuka lived on until 1982). I will put forward a few observations and speculations about master Otsuka later.

The book itself.

There were so many things about John Stevens biography of Kano that surprised me. I already knew that he was the early model for Japanese modernisation and instrumental in the survival of the cultural legacy of the Old School Japanese Jujutsu, albeit packaged into a new form (how successful he was is too big a subject to go into here), but there was so much more to the man.

Here are some intriguing facts about Kano (to me anyway):

- Kano came from the higher tiers of society, so, financially and socially he already had a leg-up the ladder. Otsuka and his good friend Konishi (1) also came from more than secure backgrounds. These advantages allowed scope for freedom and exploration, as much as Japanese society allowed at the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century. Add to that a fanatical desire to dig really deeply in their chosen field and something truly special emerges with all three men.

- Kano was a traditionalist in martial arts (jujutsu) terms, but also a moderniser who was able to get a significant number of the old school hardened jujutsu masters on-board to synthesise their teachings into modern judo… how was he able to do that?

- Kano suffered considerable set-backs as he struggled to formulate, promote and develop Kodokan Judo, however, his tenacity seemed almost super-human. Clearly the man had charisma and amazing persuasive powers, and, in the early days, led from the front – he could walk the walk!

- Amazingly, he looked towards western culture to find models that would work for the Japanese people. He admired the philosophical ideas behind western physical education but hated the modern concept of ‘sport’, which to him trivialised and subverted the purer objectives of the physical culture of the martial arts (ironic when you think of his legacy today). Interestingly, it was open contests that boosted the status of Kodokan judo in the early days (2). A real shock to me was that although Kano was actively involved in the Olympic movement (particularly the failed bid for the 1940 Olympic games in Tokyo) he was actually reluctant to suggest that judo should be included, for fear that the appetite for medals and glory would be the opposite of how he saw the reality of judo.

- Stevens says that in technical judo Kano was not a fan of groundwork, but understood it as a necessity if he was to make his point. For Kano it was 70% stand-up and 30% groundwork, Stevens quotes a saying, “To learn throwing techniques well, it takes three years; to learn effective groundwork, it takes three months”. (Stevens does not give the origin of the quote).

- It seems clear that even within his own lifetime Kano’s judo was being subverted into something he was desperate to avoid. Everything that he frowned upon in modern sporting culture was acting as a magnet to the coaches and youngsters they taught. Kano was clear in his mind what the model for judo should be and he explained it in language of high ideals, but perhaps these ideals were too abstract and contradicted where the world was actually going? Kano was swimming against the tide.

- In his working life Kano was a model professional educator. His whole career was in education, he genuinely cared about people. As a scholar and a life-long learner he was a wonderful example of an insatiable and a genuine polymath. E.g. it is known that he wrote all his early training notes in English to keep them secret from his fellow trainees. What also surprised me was that Kano is considered the father of music education in Japanese schools, being instrumental in making music compulsory for all middle and high school students.

- He was without a doubt a rebellious figure, in that he kicked back against Japanese conservative views on education and he resisted the militarisation and appropriation of Japanese martial arts to fuel war and expansionism. This would have surely ruffled a few feathers at the time. Some of his political contemporaries were actually assassinated for holding opinions similar to his.

- His successes came at a price, in that he acted as a lodestone for various martial arts crazies, obsessives and prodigies (positive and negative). Too many to choose from, but to name two; Saigo Shiro and Mifune Kyuzo (3).

- Kano died at the age of 77 on board ship on his way back to Japan. It’s just my opinion but I suspect he was just burnt out.

Otsuka Hironori and Judo.

I think it is important to explain that the terms ‘Jujutsu’ and ‘Judo’ were loose descriptions that had been interchangeable for a long time, even before Kano’s ‘ownership’ of the term as a handle for Kodokan Judo.

Regarding Otsuka Sensei; even before he reached his teens Kano’s Kodokan was becoming a major force in Tokyo and beyond, how could he fail to be influenced by it?

In 1906 Kano had opened a huge 207 mat Dojo and the standard Judo Keikogi (uniform) had been established by this time. Coincidentally, one of the earliest pictures of Otskuka Ko (as he was then named) is of him in a group photo of ‘Judo’ students at middle school wearing this new keokogi, this was 1909 and he was in his late teens. While at school he was heavily involved in judo as it was evolving and working its way into the education system. He is also in the school records of 1909 as taking part in the school’s winter training and earmarked as one of the most promising judo students. (Apparently had some particularly strong throwing techniques).

In 1908 the government decreed that all middle school students should be doing either judo or kendo. We know from Otsuka family anecdotes that Otsuka Ko’s mother discouraged her son from kendo, and he had some background training from his mother’s uncle in old school jujutsu and on top of that Otsuka was to come under the influence and tutelage of Nakayama Tatsusaburo, the middle school’s hired coach, who clearly taught him judo and opened the door to him learning Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu which is largely recognised as being one of the base-arts of Wado Ryu.

In his book, ‘Karate Wadoryu – from Japan to the West’ Ben Pollock mentions that “There is the possibility Otsuka was practicing judo at the Kodokan at some point in the period prior to him starting his study of karate-jutsu”. Clearly this possibility is not beyond the bounds of credibility, it is known that Otsuka was well connected with some of the leading lights of the Kodokan, including Mifune.

Is there any surprise that Otsuka’s concocted curriculum he submitted to the Butokukai in 1939 to register the name and the style ‘Wado Ryu’ was padded out with techniques from the established judo canon? Look at it from this angle; a huge percentage of those who went through the Japanese middle school would have a pretty good idea of what those throws were, they weren’t unique to Wado, they were common techniques. In the same way if you asked an English schoolboy the basic mechanics of manoeuvres in football, he’d be able to tell you; it is part of the system and the way physical education is taught. This is not to take anything away from Otsuka, as it is known that his grappling skill was at a very high level.

But what intrigues me the most was not the technical base of the influence of judo and Kano on Wado, but the philosophical and organisational approach Otsuka later took. Did Kano’s example act as a beacon of influence for Otsuka?

Japan was breaking the traditionalist mould and Kano’s example may have showed Otsuka that this can be done, and that the climate was right.

As an example; Kano is said to have originated the basic idea of the belt system (although the many coloured belts is rumoured to have originated as a later development in Europe). The way we work today, our hierarchies, ladders of promotion, syllabus developments all relate to how things are done in the education system – some people say it is more closely related to military systems, but that argument becomes very ‘chicken and egg’. Remember, Kano was the educationalist with a vision for the whole of Japan and the wider world (hence his involvement with the Olympic movement and the ideas of Baron de Coubertin).

Wado, like other systems rejected the long-established certification system of the Koryu (Old School) Japanese martial arts and adopted another, modernised, system; Kyu/Dan ranking. It was workable, particularly as Dojo branches then became sub-branches, then regional branches, followed by national branches etc. At some stage, somebody must have thought this was the way to go. It has a certain convenience to it. Committees sprang up like mushrooms and seniors became ‘officials’ and then, I suppose ‘suits’ (4). The move towards factoryfication became inevitable, and in many of the larger Wado organisations continues today.

Personally, I don’t look at the Kano story as just something that belonged in its historical time, there are lessons and parallels to be drawn that are just as relevant today. John Stevens did an amazing job with the book and tried to strip away any hint of propaganda and in doing so presented Kano as a formidable figure, but with human flaws. It would be a huge loss for the example set by Kano to be buried in the history books.

Tim Shaw

1 Konishi Yasuhiro, 1893 – 1983 founder of Shindo Jinen Ryu karate, an early pioneer along with Otsuka. As with Otsuka Konishi started out as a traditional jujutsu practitioner, they had a lot in common.

2 The ‘contests were billed as ‘exchanges of techniques’ or ‘exhibition bouts’ and unashamedly pitched school against school; the aim was for Kodokan judo to come out on top, and many times they did. ‘Exchange’ training also happened in the early days of Wado, as Suzuki Tatsuo recounts in his autobiography. So, this was definitely part of the culture.

3. Saigo Shiro 1866 – 1922, was a prodigy of Kano’s judo and elevated the status of the art in early contests, but he was hot-headed and his bad behaviour forced Kano to expel him from the Kodokan.

Mifune Kyuzo 1883 – 1965, another prodigious talent, sometimes referred to as ‘the god of judo’ Mifune was only 5 foot 2 inches and weighed only 100 lb but he was unstoppable and took over the Kodokan after Kano’s death.

4. A phrase that came to suggest; those who no longer actively trained but their authority came from association with Otsuka Sensei way back when.

Cover photo source Amazon Link.

Technical notes from the March 2022 Holland Course.

The notes are mostly intended for the students who attended the three-day weekend course but I will present them in a way that others may benefit. I will also steer clear of overly-complicated Japanese concepts that may take a whole blog post to themselves.

Underpinning Themes.

Some of the warm-up exercises were designed to encourage the students to actually map the lines of movement and tension throughout their body, this was done in a static (but dynamic) way, but also tracking these tensions and connections within movement, looking for an orchestrated and efficient whole-body movement.

I also wanted to encourage an attitude of ‘why are we doing this?’ to specific aspects of our training. This is something that Sugasawa Sensei has often spoken about, although Sensei has always stressed that an intellectual understanding alone is not enough; these things must be explored through training and sweat.

How to develop an integrated dynamic to your technique.

This was addressed initially through examining the non-blocking, non-punching hand, what I sometimes tongue in cheek call the ‘non-operative side’. Of course the pulling/retracting hand is not really exclusively about the movement of the hand/arm, it is actually working as a result of what is happening deep within your own body, it is an extended reflection of the orchestrated work of the pelvis, the spine and the deeper abdominal muscles, this combination of factors energises the limbs and the energy that originates in those areas ripples and spirals outwards to create what appears as effortless energy all firing off with the right timing – well, that’s the objective anyway.

Some movements are designed to challenge your relationship with your centre.

This was where we focussed on Pinan Sandan, which seems to pack so much in. Of course, it exists in all movement, Otsuka Sensei’s intentions for Junzuki and Gyakuzuki no Tsukomi are yet another more extreme example. As in Pinan Sandan, you can be extended and stretched to such a degree that you have to acknowledge how close you may be to losing your centre and easily destabilised.

A technical challenge!

How many different ways in Wado movement are we demanding of the various sections of our body to either move in contradictory directions, or to lock-up one section while allowing free movement in another? A clue…It’s all over the place.

Destabilising your opponent.

In this one I asked that we really try to think three-dimensionally (if not four-dimensionally, if we include a ‘time’ factor). We want to destabilise our opponent in ever more sophisticated ways – one-dimension is not enough for a finely-honed instrument such as Wado. We can tip, tilt, crush, nudge, we can even use gravity (amplified through our own body movement), we can also take energy from the floor; all of these are part of our toolkit (on the Saturday we did this through what can usefully be described as a ‘shunt’ into our partner’s weak line).

What do our ‘wider’ stances give us?

Side-facing cat stance is the widest stretched stance you will ever be asked to make (a major demand on the flexibility of the pelvis) with Shikodachi as a slightly lesser challenge, but why? What does it give us? Of course, with all of these things there are a number of actual ‘benefits’ but our focus was on the dynamics of opening the hips out to the maximum. Not in a static way; but instead as an empowered dynamic, the body operating like a spring whose tensions wind and unwind supported by the energisation of the entire body. It’s easy to see and feel when it’s not working as it should, but you just have to put the work in.

Of course, over the weekend we strayed into many other areas, but I wanted these to be our take-aways.

Tim Shaw

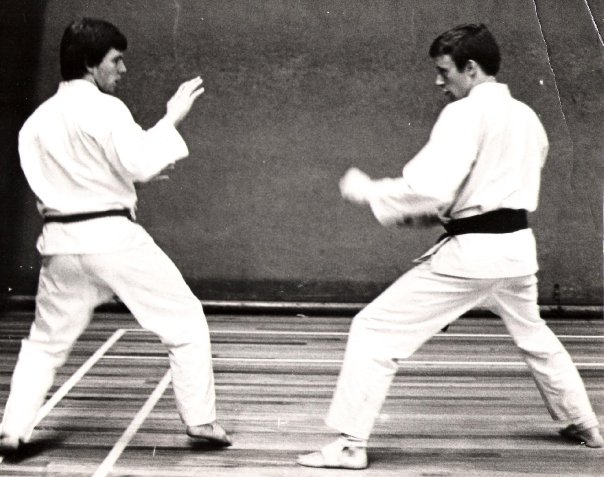

Sample – Part 12, Early days in Leeds.

1978 through to 1981. Undergraduate years at Leeds Polytechnic, studying graphic design.

Living in Headingley (and later Harehills) and taking over the running of the Leeds YMCA Wado Dojo under the authority of Suzuki Sensei’s UKKW.

Post Mansfield and my arrival in Leeds had given my karate full licence to develop in its own way – of course within the constraints of mainstream Wado and very much marching to the UKKW/Suzuki drum. In my own head I reckoned that the apprenticeship had been served.

By that time I had pretty much decided that competition karate was not going to give me what I needed. Although I did enter competitions in my early years at Leeds I became disillusioned with how things were run (e.g. Carlisle, Huddersfield, the Nationals). I had no desire to build a team to rival the top teams of the day, it just wasn’t part of my agenda (the same Leeds Dojo became famous only after my departure, after Keith Walker took over and embraced the competition world with his characteristic energy and enthusiasm).

Although I was building a Dojo, it was all geared towards ‘Project Me’. I think I must have figured that if I was going to be running the club with some authority as a twenty-year-old, I had better make sure that I could walk the walk.

Supplementary Training.

For me it was split between Dojo time and supplementary training time; and it was in this supplementary training that I became quite creative; basically, I was willing to try anything.

I started off living in student halls of residence at Beckett Park, Headingley, north of the city centre. While I was there, I gained permission to train in the weights room of the PE college, Carnegie, which was always interesting because you never knew who was going to walk through the door. I hardly saw any of the rugby set in there; the only heavy lifting they were interested in was in the Union bar. It became a bit of a joke, the piss-head rugby crowd were only ever seen in the evening, while the serious athletes were only ever seen at 6am for their morning run – always an early night for those people.

In the weights gym were specialist athletes; like the canoeists, guys with massive shoulders, yet tiny skinny legs. And throwers; lots of throwers, javelin, discus and shot; many of them trained by Wilf Paish, a small man who would drift in and out of the gym and never seemed to smile. Paish had his finest hour in the 1984 Olympics as mentor to Tessa Sanderson and Fatima Whitbread.

I initially tried to connect with the Shotokan group on the campus, but the Shotokan big cheese must have seen me as too much of an outsider and let me know that I just wasn’t welcome. He told me to go and train in a corner; as a result this was a very short-lived experience.

Always looking for a new opportunity to train, I used the gym equipment at the Leeds Playhouse when I was in the city centre, sometimes lunchtimes, sometimes early evenings. This was the ‘Multi-gym’ type equipment, but it was very manageable and I was always able to get a reasonable workout.

I even trained with the Leeds University boxing club, however, it interfered too much with my technique. I didn’t let the trainer know I’d done anything before; he liked how I used my waist, but it wasn’t to be; but it was worth a punt anyway.

On top of this I did an awful lot of running. The Headingley parkland and running track were perfect for that, and with all those PE student-types around, it just seemed to be the done-thing, although I always found the early morning runs a real chore.

Lifestyle.

I never lost the habit of walking everywhere; averaging four times a day from Headingley to the city centre site, back and forth; two miles each way. I enjoyed the walking, then, as now, it gave lots of time for thinking and it never felt like a hardship.

The few times I took the bus I always felt resentful, this was magnified by the lousy attitude of many of the bus drivers, who seemed to think that passengers were an inconvenience to their working day. They hated having to give change and were brutal on the brakes when they realised that people were precariously balanced stuffed into the aisles because the seats were all taken; a quick stamp on the brake pedal and people would tumble like skittles! I suppose it gave them some fun in a working day.

As I didn’t drive at that time, everything was on foot; I never saw the inside of a taxi, they were just too expensive.

Parties and events were just word of mouth, an address, a name, or sometimes a crudely printed ticket with the date and time on it. Pre-Internet days meant holding information and a complex map of the city in your head, and any networking seem to operate at the same telepathic level as Aboriginal ‘Song Lines’, we just ‘knew’ where people were liable to be at any point on any given weekend night; spookily accurate in its psychic predictions.

The Leeds Dojo.

Gradually I had picked up a small group of karate students who were all about the same age as me; some were college kids from various courses. This enabled me to really start to pump the official twice weekly Dojo sessions at the YMCA in the city centre.

I don’t for a minute think that we were very technical – certainly not by today’s standards. We used to joke that half of the class time was dedicated to calisthenics; a bit of an exaggeration, but not far off. After I’d left Leeds, Keith Walker had taken over the Dojo; as he’d started with me as a teenager, he very much followed the tradition I had established, and, a visitor from North Yorkshire, a female karate-ka who trained at the Settle Dojo, commented that when she went to train in Leeds (post 1982) Keith had put her through a session that was mostly boot-camp callisthenics. But, to his credit, he soon found his own way of doing things.

But, being honest, a lot of the content of the training was for me; it sounds a bit selfish but my thinking was that if the students benefitted from it then all well and good. In those early days, I set the pace, I directed the exercises and I enjoyed devising new ways to work the body. We may not have been terrifically technical martial artists but we were really fit.

Eventually, twice a week was not enough for me.

The YMCA were quite happy for us to book the training space for times when things were quiet; so early Friday evening was an additional class; about three hours of extra training. In the first part of the session it was often just me and young Keith Walker and then others turned up as the evening went on.

Saturday mornings at the YMCA.

But the most enjoyable session was the Saturday morning class.

Because nobody wanted the basement gym at the YMCA on Saturday morning, we grabbed it as an extra slot. Although, living a student lifestyle, training on a Saturday morning was a bit of a stretch. It developed into one of our most creative and free-form sessions, and I think those who took part really enjoyed the buzz.

The Saturday class was for two hours. It always started with about 45 minutes of kata, though this was a token, almost a warm up.

We then went into crazy sets of relay runs (it was a long narrow gym) punctuated with circuit training-style intervals; squats, press-ups and every exercise I could throw into the mix. By the time we’d got to the end of that we were a sweaty mess and, crucially, well warmed up for the sparring. This was the ‘light sparring’ I had ‘borrowed’ from the Wolverhampton team. It always started out in the right spirit, but the more we got into it the heavier it got, but nobody seemed to care, it was a total adrenalin rush, and, because we all trusted each other, we knew how to push each other’s boundaries; high energy, yes, but full spirited.

The bonus of the Saturday morning was that we had access to the most wonderful hot water showers after training. Rinsing off the sweat with muscles feeling like mush, the euphoria after the training was better than any massage. You could have poured me into a bucket.

On many occasions the Saturday morning training was the prelude to another bigger training session in the afternoon. We would often grab a quick lunch at the YMCA cafeteria and then catch a train from Leeds to Doncaster to train for a further two or three hours with either a Japanese Sensei or another guest instructor at the Doncaster Dojo, also allied to the UKKW.

This arrangement led to some interesting and intense Saturdays.

An ‘apex’, and not untypical weekend for us, was probably:

Friday; three hours training.

Then leave your sports bag and sweaty gi in a left luggage locker in the railways station.

Go out on a heavy night, including clubbing till about 2am.

Crawl into bed, about 3am.

Up early Saturday, collect the sports bag from the station.

Two hours of hard work in the YMCA gym in a stinky, sweaty gi; no chance to recover.

To Leeds station to catch a train to Doncaster, more training.

Back into Leeds for whatever the night offered; phew!

We didn’t congratulate ourselves that we were doing anything unique; we had nothing to compare it to; it was just what it was, we just plunged in, we had the energy to do it and youth was on our side. It is only in retrospect that I realise how bonkers it was. But, it was really about being young and pushing at any boundaries we could find.

A training diary from the time details how I would sometimes clock up twenty hours a week of training in various forms.

It is often commented on that youth is wasted on the young; I am sure that in those days we were convinced we were indestructible. I suffered relatively few injuries; a niggling lower back problem, a broken toe, broken nose, various hand injuries (thumbs wrenched back) and an unfortunate and very stupid stab injury to my thigh, to which I still have the scar, which (typical of me) I had bandaged up and trained through – because I was indestructible and would let nothing stop me, and hence the stitches wouldn’t hold and the wound opened up and now I carry a bigger and uglier scar than I needed to – fool that I am. (The course on that day was a squad training session under the then England coach Eddie Cox).

Influences and opportunities.

But what about input? Where was I getting my influences from, how was I able to develop?

So much must be credited to the initiative and enthusiasm of the Genery family who ran the Doncaster Dojo. They kept us well-informed about courses they were hosting and never failed to invite us. All of the main Japanese Sensei were invited to run courses and gradings at the Doncaster Judo club; Suzuki Sensei, Shiomitsu, Nishimura, Sugasawa, Sakagami as well as courses with England coach Eddie Cox, Charles Longdon-Hughes and world champion Jeoff Thompson. Add to that the big UKKW courses, Winter and Summer and some particularly iconic courses organised in places like Sheffield and Newcastle; there was so much happening. It is often assumed that the London scene for Wado karate was where it was all happening, but Suzuki Sensei and the other Japanese Sensei were encouraged to go all over the country and the demand was there. It must have been a good way of making a living as there was never a course that was unsupported, and that was quite something in an age that was pre-Internet. All communications took place through mail and phone calls. But, for me, living as a student in Leeds, we didn’t have a phone and had to make any vital calls through payphones, so it was all word of mouth.

As I worked on my body and predominantly my fitness level I probably undervalued the technical world. Not that I taught or practised sloppy techniques; I was very exacting in refining my own skills, but only really to the demands of the time. I had been well-tutored in the syllabus book and knew what was required to pass gradings and perform a fast and sharp kata; but there were other fish that needed frying.

Fight training.

In retrospect I enjoyed exploring creativity through fighting. Sparring was a crucible for me, as I chased ideas and explored new emphasis. I remember that at one time I got really excited about rhythm and setting up tempo patterns and then breaking them; a kind of ‘leading’, a disruptive interplay.

We tried to engage with contact work, but we were always short of equipment – I think that must have been where the boxing experiment happened.

It must be said that all of this did not happen in a vacuum. We developed some useful contacts through other martial artists, other karate styles. We met some of them through competitions; although, as I have said, our competition experiences were not always fruitful.

Other courses.

I attended most of the major courses and encouraged my students to do the same. I think I only missed the 1979 summer course, a landmark course because this was Sugasawa Sensei’s first summer course in the UK. I had seen him before at the 1978 Nationals, with moustache and long hair; but the 79 summer course changed all of that for him, as it was there that he reverted back to the shaven-headed look he’d had in Japan and has subsequently stuck with ever since.

The summer and winter courses from the Leeds days followed the same pattern as previous years; though the venue of the summer course changed to Great Yarmouth and then Torquay.

But, to return the focus to the training.

These courses were marked by their large numbers. Nowadays big courses across Wado organisations are boosted by huge contingents from abroad; this was not the case in the late 70’s and early 80’s, although the winter courses did tend to attract some Scandinavians and a few Dutch. The attendees were primarily UK-based and it was good for networking, and to train with different partners. Which in itself was a bit of a lottery; you could get some really outstanding, hardworking partners or some that were either lazy (too much wanting to talk about or analyse what we were working on) or some that were just clueless. Over the years I did partner Japanese Sensei who were there for the training; Fukazawa Hiroji was new to the Suzuki way of doing things and when I partnered him he asked me to teach him the Suzuki Ohyo Gumite, which I was happy to do. (In later years I partnered Tomiyama Keiji of Shito Ryu on a large course in Guildford; a real pleasure.). These were all great learning experiences.

Grading for 2nd Dan.

I took my 2nd Dan on the Summer Course in Great Yarmouth in 1980. There were a clutch of prospective 1st Dans, and the only ones above that were myself for 2nd Dan; one of a bunch of brothers who had emigrated to Australia for 3rd Dan, and another British emigree from Sweden who was going for 4th Dan; which made fighting all the more interesting. The most senior, the Swedish/English guy had a tough time in the fighting and the Australian gave him a real drubbing, I felt quite sorry for him, he never really got started, the Aussie was all over him like a rash. Then came the time for me to fight Mr Sweden, but he’d had all the fight knocked out of him; so, it was a bit of a non-event. Then I had to spar with the Australian… I admit it here, it was a tough fight, I went with the idea that attack was the best form of defence, I was definitely outclassed, it was almost impossible to stifle his aggression, but I felt that I held my own, I certainly didn’t disgrace myself – one of my most memorable fights.

Suzuki Sensei.

On these courses the majority of my time was under Suzuki Sensei. He insisted on taking the black belts for himself, as befitting of the senior man. Shiomitsu and Sakagami had to be content with switching the brown and green belts between themselves.

Suzuki Sensei was gruff in manner and thought nothing of kicking your leg from under you and growling at you if it wasn’t up to his measure. He also had no restraint in showing his amusement when someone screwed up. His humour had a cruel side to it. He had a favoured take-down which involved grasping your collar from the back and pulling you backwards at great speed. Tokaido gis at that time had a particular weakness; although they were expensive, they used to tear at the back of the collar, near the shoulder. I think he knew this and when he needed to demonstrate the take-down I’m sure he looked for the Tokaido label, and, sure enough, ‘rip!!’ an expensive gi top split all the way down, and he would just walk away chuckling to himself.

When Suzuki Sensei was teaching kata it was all ‘Ichi, Ni, San, Shi…’ but when Shiomitsu taught kata he would start out like that and then become impatient and say, ‘practice by yourself’. I actually found this quite useful as I could really dig into repetitions and try to get under the skin of what I was doing, with the added bonus of Japanese Sensei prowling round to correct your form and maybe field questions – although the ‘fielding of questions’ was very much a later development, Suzuki Sensei did not encourage questions.

Suzuki taught by physical example; ‘like this!’ he would say, and snap sharply into position. He was very ‘hands-on’ and demanded that you mirror his moves; he almost wanted you to ‘be him’, which was a challenge for me as we were physically quite different. I make no bones about it and stick by my theory that karate was designed by shorter guys, for shorter guys. I first realised this through experiencing Suzuki’s physicality, but it was further reinforced by having to train alongside Clive Wright and Frank Johnson. These two were physical carbon copies of each other body-wise. Quite short and light in build, closer to the Suzuki ideal. I remember training alongside Clive in Yarmouth and being puzzled as to how we were both doing the same move to the same count but he was getting to the end of the motion half a beat before I was? And then I realised what the answer was, ‘short levers’; because of my limb length being longer than Clive’s (or Frank’s) I had to cover twenty inches of distance to their twelve! No wonder I was behind!

I have often pondered this conundrum; the challenge for the taller person is to aim for the same speed as the shorter person, at the same time being aware that with the longer levers there is going to be a bigger challenge to move as an integrated whole – put simply; the ends of the limbs may have the advantage of creating a longer reach but this leads to the extreme ends of the movement being significantly divorced from the body’s central core; and it is this relationship that is integral to efficient movement in Wado.

Training methods and instruction.

On these summer and winter courses there was still the emphasis on going up and down in lines; which is a very efficient way of managing the large numbers. You would think that it was very easy to get lost in the crowd, but there were so many Japanese instructors to oversee proceedings that you always felt eyes upon you. But I am sure that these large numbers hindered the opportunity for the more bespoke coaching that is needed to progress – particularly post-Dan grade. I can’t think of any course that I went on in those years where the numbers were so few that you were able to enjoy a unique access to Japanese instruction. The only instances that came close was when Sakagami Sensei was teaching at the Doncaster Dojo; but this coaching didn’t happen in the Dojo, it happened in the changing rooms afterwards. Sakagami on his own was always friendly and talkative, though always earnest and enthusiastic, once you got him on a favoured theme. But in those changing room chats he used to get carried away and we were stuck in there for ages; so much so that the organisers seemed to be frustrated in their efforts to clear up and lock up. He just went on and on, but it was so interesting and so informative.

Tim Shaw

Featured image: Mark Harland and Tim Shaw in the Leeds YMCA basement gym, circa 1979.

You’d better hope you never have to use it – Part 2.

“Smash the elbow”, “tear the throat out”, “snap the arm like a twig”, “gouge the eyes with your thumbs”. I have heard these things said by martial artists during classes. But I find myself asking, how do you know? and have you ever done that? Have you ever used your thumbs to gouge out somebody’s eyeballs? And on top of that, how do you know you won’t freeze like a rabbit in the headlights? Or, how do you know if you have enough resilience (or lived experience) to be able to suffer a terrible beating before you get a chance to put in that one decisive game-changing shot?

Empirical evidence versus anecdotes.

Effectiveness, can you prove it? Can it be quantified in a scientific way? Is the data available?

Every martial artist probably has a dozen stories as to why their martial arts method is effective as a fighting system and none of these incidents ever happen inside the Dojo – how could they, it’s supposed to be a safe training environment?

I have my own ‘go-to’ anecdotes, but equally I have another set of anecdotes where martial arts practitioners have come unstuck – but nobody talks about those, least of all the people who it has happened to (understandably). [1].

Anecdotes may be fun to recount but all they do is muddy the water, they are too random to qualify as evidence. And, if you look at some of these stories in the cold light of day you often have to wonder about (a) their veracity, (b) which way the odds were stacked, (c) whether elements of luck or chance were involved; but one thing is clear, they cannot really be used as definitive proof that your system works, after all, the system is the system and You are not the system.

The anecdotes may suggest that in certain circumstances your chances of coming out on top in a violent attack might be slightly higher – but they could also suggest that you might come out worse (probably because of over-confidence, or an unrealistic evaluation of your own ability).

The problem with fantasy.

Now compare that to movie fantasies of physical confrontations. I cite two examples that come to mind.

The first being Tom Cruise as Jack Reacher, where Reacher takes a bunch of guys on after they offer him out from a bar ( link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hu1MtT_S3bc

The thing is, deep down, we all want it to be like that.

And then Robert Downey Jnr as Sherlock Holmes in a bare knuckles contest (link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-z5139CW1I

This last one is about as extreme an example as is needed to make my point that fantasy is fantasy. (To paraphrase Mike Tyson, ‘Everybody has a plan until they get a punch in the mouth’.)

The Sherlock Holmes example is akin to treating violence like a chess game – if I plan and think several moves ahead then my plan will bring about the downfall of my opponent…. wrong. When it gets to the ‘trading punches’ stage you have already entered the world of chaos, thus ramping up the unpredictability exponentially.

It is potentially fatal to confuse Complex with Complicated [2] and the zone of chaos is indeed Complex. This is why those who are supremely skilful at navigating the Complex world have to do it without thought, artifice or calculation, they are like expert nautical mariners in a tossing sea, who work on instinct, they have an overarching understanding of Principle, their skills are not a bunch of cobbled together tricks that they have memorised hoping for that moment to happen.

I know that there are critics of the Principle angle in martial arts (particularly Wado), usually they fail to understand it and ask, what is this ‘Principle’ thing anyway? I am tempted to reply with something like the Louis Armstrong quote about the definition of jazz, “Man, if you have to ask what jazz is – you’ll never know”. (See my blog post on ‘Fast Burn, Slow Burn Martial Arts’ for a clue as to how it works). These same people remind me of the ‘Fox with no tail’ a moral story from Aesop].

When people talk about ‘functionality’, ‘functional combative skills’, this has to be about effectiveness, surely? But You can’t talk about that without some form of measure, if there is no measure then it’s all opinion and as such, we can take it or leave it. The person who makes the statement can only hope that we trust their opinion as an ‘expert’, but again, an expert based on what experience; their ability (as proven) to ‘snap someone’s arm like a twig, or gouge their eyes out’? I realise that there are people out in the martial arts world whose whole authority rests on this issue and it’s not my place to call them out, particularly as I also have no experience of ‘snapping arms’ to support any claims I make, but just apply a little logic to it.

Of course, I reckon that if I take my opponent’s elbow over my shoulder and exert a forceful two-handed yank downwards I might be able to ‘snap his elbow like a twig’, but I doubt he’s going to let that happen without a hell of a struggle (unless I am Sherlock Holmes of course). Meanwhile, he has barrelled into me, knocked me on my back and is sat on my chest raining punches into my face, and then his mates join in to kick me in the head for good measure – elementary my dear Watson.

Looking for evidence in history.

I feel I have to address this one. Anyone who looks for evidence in history is on to a sticky wicket. History is notoriously unreliable. We know this because current historical revisionist methods are revealing that many things we thought were true may not be so. For example; everyone knows that it is the victors who write the history.

If we take our history inside Japan and Okinawa and we listen to serious, open-minded researchers, we find that some of the things we took for granted may well not be true.

To give a few examples:

- Zen Buddhism does not have the monopoly in Japanese martial arts, certainly karate is not ‘Moving Zen’.

- The 19th century Samurai were not the apex of Japanese martial valour and skill. Set that two or three hundred years earlier and you might be about right.

- Okinawan martial arts were not the result of a suppression imposed by Japanese Samurai; it was not that simple. Okinawan people were generally peaceful and society was well-structured, it certainly was not the Dodge City that some people like to suggest, it seems that the martial arts of Okinawa reflected this, an extreme martial arts crucible it certainly wasn’t, certainly if you compare it with what was happening in Japan between 1467 and 1615. I don’t point that out to discredit the Okinawan systems, it’s just an observation and there were exceptions, e.g. Motobu Choki, who certainly had his ‘Dodge City’ moments.

As time moves forward all we are left with is the mythologies, hardly something to judge the functional abilities of teachers who are long dead, so all we have available is guesswork, assumptions and opinions; not really scientific or objective. So, anyone who wants to hang their ideas on that particular hook would be wise to keep an open mind.

How would martial arts work in a defence situation? A proposition.

To answer this, I would speculate that there are several high-level outcomes that are possible, and none of them look anything like either the movie fantasy image, or the types of techniques that are, ‘a bunch of cobbled together tricks that have been memorised hoping for that moment to happen’ [3].

- The highest level has to be that nothing happens, because nothing needs to happen. The world calms down and order rules the day; chaos is banished.

- The next highest level is probably where the aggressor just seems to fall down on his own. Here are my two nearest assumptions on this (one anecdotal and the other historical – but after all, I have to pluck my examples from somewhere). The first is a story about Otsuka Sensei dealing with a man who tried to mug him for his wallet in a train station. Otsuka just dealt with the guy in the blink of an eye and when asked what he did, he replied, “I don’t know”. The other is the historical encounter between Kito-Ryu Jujutsu master Kato Ukei and a Sumo wrestler who twice decided to test the master’s Kato’s ability with surprise attacks, and both times seemed to just stumble and hit the dirt [4].

- Anything below those two levels would probably involve one single clean technique, nothing prolonged, maybe appearing as nothing more than a muscle spasm, nothing ‘John Wick’, certainly nothing spectacular – job done.

- Then you might plunge down the evolutionary scale and have two guys smashing each other in the face to see who gives up first.

Conclusions:

The original objectives of these two blog posts were to challenge the assumptions we seem have made about the nature of self-defence (in its broadest interpretation) and to put forward some different angles, explode a few myths and to present the idea that all that glitters is not gold.

I don’t have the answers, but then it seems, neither does anyone else. But we shouldn’t just throw our hands up in the air. Keep on with the focus on defending ourselves and refining our technique and by all means teach self-defence as a supporting disciple or on dedicated courses, it is a brilliant way for martial arts instructors to engage with the community in a positive and confidence building way; however, keep it realistic and not just fearful.

For those who claim that their approach has more ‘functionality’ I would humbly suggest that that you might want to look towards the key questions; objectively, how can you prove that? Maybe what you are asking for is a leap of faith? My view is that the data is not there and that it is just lazy logic. [5]

There are people who want to claim their authority from the ‘short game’, while I would suggest that there is another game in town; the ‘long game’. Targets really need to be aspirational and ambitious, not ducking towards the lowest common denominator, i.e. the ‘fear factor’ of the anxious urbanite. Your authority is not derived from your ability to ring the metropolitan angst bell; or to yank the chain of the frustrated metrosexual male who feels he is cut adrift and fretful about his role in contemporary society and lost in a maelstrom of surging confusion.

The bottom line is; get real and dare to think differently.

As a last word, these posts are not meant to be definitive, or to cover all aspects of self-protection. I could have included comments about how the law views self-defence, or how much mental attitude is a part of self-defence, or adrenalin, fight and flight etc, without even mentioning the number of young men in the UK who die through stab injuries. But maybe another day.

Tim Shaw

[1] One event happened fairly recently where I had bumped into a martial artist from another system, an acquaintance, in a nightclub. He’d had a drink or two and proceeded to bend my ear about how ‘the trouble with most martial artists is they have never been in a real fight, never trained for it, etc.’ And, as if the God of Irony was looking down upon him; within seconds of him waving me goodbye, he crossed paths with the wrong person and ended up as a victim, laid out and bleeding. I guess he didn’t get the chance to ‘snap the arm like a twig’.

Be careful what you wish for.

[2] See my blog post on Systems. https://wadoryu.org.uk/2020/01/29/is-your-martial-art-complicated-or-complex/

[3] These methods often assume that the opponent is going to present themselves like a bag of sand and allow you to engage in an ever-complex string of funky locks, take-downs, arm-bars etc. etc. Sherlock Holmes would definitely approve.

[4] Source: ‘Famous Budoka of Japan: Mujushin Kenjutsu and Kito-ryu’. Kono, Yoshinori, Aikido Journal 111 (1997). According to Ellis Amdur in his book ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’ this is pure Principle and Movement in practice (my paraphrase).

[5] Similar to the way people talk out about ‘life after death’, i.e. how do you know? Conveniently, nobody has ever come back to tell us. Ergo; you never have to validate your claims.

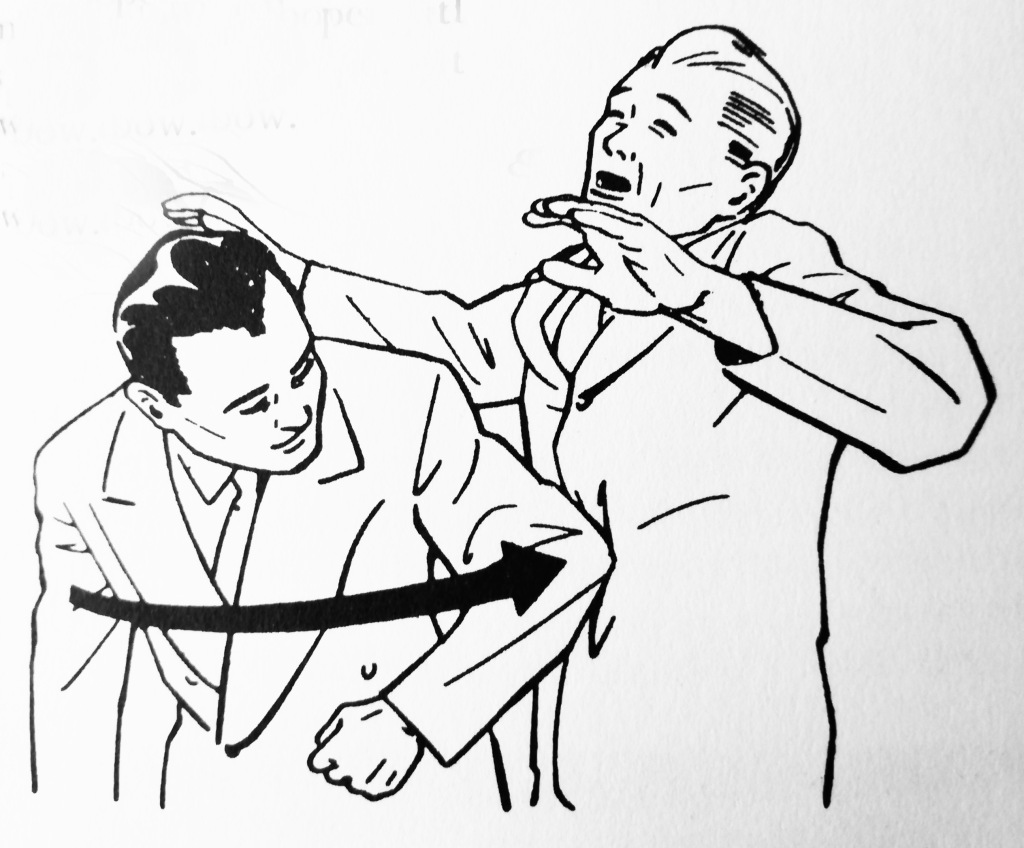

Image credit: Kiyose Nakae ‘Jiu Jitsu Complete’ 1958.

You’d better hope you never have to use it – Part 1.

An alternative view on self-defence and ‘effectiveness’. I have been thinking about this for a long time now. Every time I see this subject brought up on martial arts forums, I find myself shaking my head; where is the objective clarity? Where is the cold scalpel of logic which is needed to cut through the mythology, pointless tautology and hyperbole? In addition, why doesn’t someone call out those who are too quick to erect a whole forest of straw men; those who set up false equivalents and apply simple answers to complex questions?

Self-defence, what does it even mean?

Taken at face value it’s supposed to be our raison d’être, but we know that Japanese Budo has worked hard to raise itself above primitive pugilism, and the inclusion of firearms into the mix has brought in an element of semi-redundancy, particularly in certain societies around the world. But we still have the hope that we can take the ethical and moral high ground through the philosophies of Budo, which, in itself is not above hyperbole (try, ‘we fight so that we don’t have to fight’, I know what it means, but I suspect I am in a minority).

Real Violence.

We tell ourselves that we are training so that we can protect ourselves against physical attacks by unknown (or even known) aggressors who clearly mean us harm. Realistically, most people have fortunately never really experienced that (here in the UK, despite what the papers want to tell us, we live in quite a peaceful society [1]). Hence, what people do is carry around an image in their heads of what that violence may look like; but, based on what exactly? Mostly, I suspect it’s a mish-mash of choreographed movie violence and random CCTV footage on YouTube; it is highly unlikely it will be based on real experience.

What does real violence look like?

I don’t like doing this but unfortunately, I have to base my proposition on a degree of personal experience, mostly (but not exclusively) from my younger days.

A list of what real violence tends to be:

Random, irrational, devoid of humanity (and often bereft of conscience), chaotic, usually spontaneous, ugly, seldom prolonged (most likely, over in just a couple of seconds), all too often cowardly with any elements of restraint removed by the effects of alcohol or drugs. Not in the least bit glamorous and hardly anybody comes out of it as a hero, and certainly nobody calculates the consequences of their actions.

It is this last one I want to look at in a little more detail. (Here’s where ‘You’d better hope you never have to use it’ comes in). I’ll start with; if you make a decision to punch, kick or elbow someone in the head, you’d better be prepared to live with the consequences.

One thing that tales from news media can tell us quite graphically and accurately, is the results and the aftermath of a physical assault; whether it is initiated by the aggressor or the defender, it doesn’t matter, James Bond or Jason Bourne never have to give a thought to the ‘bad guys’ they ‘take out’ in a fist fight, and neither are we, as an audience, expected to; the plot just rolls on. But that is the fantasy.

Read this account of a 15-year-old boy attacking a man with the so-called ‘superman punch’ resulting in the man’s death https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jul/25/polish-man-arkadiusz-jozwik-killed-superman-punch-court-hears

Lives ruined, families traumatised and all for what?

Someone once pointed out to me that all those techniques that are most effective in so-called self-defence situations can result in life-changing injuries and will most likely cause you to end up in court.

Please don’t misunderstand me, I am not advocating passivity or a total abrogation of responsibility, just a balanced grown-up attitude as to whether one is prepared to go for the so-called ‘nuclear option’ or not [2].

Practice and Theory.

As regards teaching self-defence classes; there is a wonderful contradiction worth considering. Nobody in the history of martial arts has EVER argued that theory has value over practice, but maybe in terms of practical, realistic self defence it does?

It is possible that if measured on results alone the value of theoretical knowledge of personal protection may outweigh that of learning hands-on physical skills.

When I designed my own self-defence courses (outside of the Dojo environment) I always factored in a theoretical aspect; a sit down and talk and explain. This would cover such things as, threat recognition, de-escalation of aggression, awareness, specific grey areas, psychological indicators and basically heading things off before they became a problem. All of these things I have NEVER taught in the Dojo, mostly because we just don’t have the time, and I suspect I am not alone in making that admission; but how ironic, here we are as martial arts specialists and we don’t have the time to put in these very important elements. [3].

The cynical exploitation of the fear factor (Self-Defence as a business opportunity).

I get it, everybody has to make a living. But maybe we should draw the line at people who feed off the fear of others. In this we find the worst excesses of the self-defence ‘industry’. Please don’t misunderstand me, most people who teach self-defence are well-intentioned and probably do a really good job, but a red flag for me is when they press the ‘fear’ button, because they deliberately feed off the darkest nightmares of the anxious urbanites. For the worried town dwellers, the fear is real, but it may well be a product of a wider malaise, an existential crisis marked by alienation and the decline of community, as well as the cult of the ‘self’; (‘me’ rather than ‘us’).

I am convinced that there is both a male version and a female version of this fear. The female version is of course very real and is wrapped up in the complex world of the politics of the sexes and goes back thousands of years. I wouldn’t even think of beginning to understand that, it’s a real tiptoe through the minefield and seems to be getting worse rather than better.

The male version is easier to understand.

There is a profound identity crisis going on with young males; they just don’t know who they are and this often affects their views on how to respond to aggression or threats from other males [4]. Tradition and history say one thing; a view that is supported by biology; but contemporary society says that there is no need or place for antelope hunters and skinners or people wielding big heavy swords like Conan the Barbarian. I am convinced that a secret desire of most males is for the advent of the zombie apocalypse, just to give them an excuse to use that baseball bat kept near the door ‘just in case’; an adolescent male fantasy. [4]

But, to return to the idea of the ‘cynical exploitation of the fear factor’. I am convinced that some of the people who have found a niche in trading off urban anxiety have been (in part) influenced by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (you might find it mentioned in books on modern marketing). If you can convince people that their fears are justified and that their whole existence is under threat in a decaying society, and your solutions will act as an antidote, they will come flocking to your door and you’ll be laughing all the way to the bank.

Am I arguing against the teaching of self-defence?

The answer to the above question is a resounding ‘No’.

As far as I am concerned, when I have taught self-defence courses it made me feel that I was actually giving something back to society, and feedback received said that some of the knowledge gained actually helped people out of some sticky situations, so another feelgood factor. It is stripped back martial arts, a bit like stripped back First Aid courses, it might give someone the confidence that they need in an emergency, it might save somebody’s life. Every little helps.

The fuller argument will be fleshed out in part 2.

Tim Shaw

[1] It would be much more objective if people would at least consult the statistics.

- Most people are murdered by someone they already know.

- Young men are in greater danger from random stranger attacks than young women.

- Terrorist attacks are so rare that it is inevitable that they hit the headlines and achieve their warped objectives of setting up ripples of fear through the population. As an example; In 2001, road crash deaths in the US were equal to those from a September 11 attack every 26 days.

[2] ‘The Nuclear Option’; a willingness to take things to the most extreme end of the spectrum, even if it means your own destruction. I.E. no serious world leader would ever admit to be willing to press the nuclear button; it’s just admitting to a form of suicide that embroils all the people you are responsible for into your own folly.

[3] Isn’t it odd to think that there are people in the martial arts community who consider kata a waste of time and compare it to the comical practice of ‘land swimming’, as opposed to swimming in water. Yet here we have a ‘land swimming’ example which maybe does work. Or perhaps that in itself is a false equivalent, as this isn’t really ‘land swimming’, it’s more akin to getting advice from a lifeguard about rip tides and safe swimming zones – which will possibly save your life and keep you from drowning?

[4] There is a section in a book I would recommend, ‘The Little Black Book of Violence’ by Kane and Wilder, which asks the question, ‘is it worth dying over a mobile phone?’. The answer is clearly ‘no’, but in the heat of the moment… Also, I do remember, years ago, an ad in martial arts magazines, which featured a photograph of some kind of glamour model with the headline, ‘Could you protect your girlfriend?’.

Image credit: Kiyose Nakae ‘Jiu Jitsu Complete’ 1958.

The Martial Body.

Physical culture and martial arts have always been inseparable. Your physical properties/qualities have to aspire towards being the nearest match to the tasks you are expected to perform.

For me this throws up several questions:

So, how does that come about?

Are those physical properties a product of the training itself?

Am I perhaps talking about utilitarian strength versus strength for strength’s sake?

How strong do you have to be?

How is ‘strength’ defined within the traditional martial disciplines (is ‘strength’ even the right word, or the right measure)?

I am not going to get into the discussion about the merits of supplementary strength training; instead, I want to explore the subject through a very specific example.

Kuroda Tetsuzan Sensei.

In past posts I have made reference to Kuroda Tetsuzan Sensei, a modern day Japanese martial arts master, very much of the old school. Kuroda has an impeccable reputation amongst martial arts specialist who ‘know’. His ability is astounding.

He is the inheritor of the Shinbukan system which contains five disciplines within its broader curriculum; including the sword and its own Jujutsu system.

Kuroda has been a touchstone for me; the YouTube snippets have me totally spellbound; I have watched them so many times. Published interviews contain amazing insight and his ideas chime very closely to things I have heard in well-informed Wado circles.

This post is inspired by an extensive interview Kuroda Sensei gave in 2010 (published by Leo Tamaki ) and, to develop my theme I will make specific references to points made within the interview.

What really interested me was Kuroda Sensei’s back-story; the environment he was raised in as it related to the martial arts. Starting at the family home. In the interview Kuroda suggests that it was virtually impossible for him to avoid the all-pervading atmosphere of traditional Budo; it was as natural and essential to him as oxygen; in his domestic setting the noises of training were as much a part of his environment as birdsong.

In the interview Leo Tamaki does an excellent job of trying to pin Kuroda down to specifics about the physical side of the training, (I almost get the impression that Tamaki had tried to second guess the answers and that maybe Kuroda’s replies took him by surprise).

Kuroda’s father, grandfather and great uncle were brought up as martial artists of the old school, and, at the family home where they trained, there was only a thin partition between the living area and the small Dojo. In the interview, Kuroda Sensei made a reference to the physical qualities of these men:

“When we look at my grandfather’s body, or his brother’s we are impressed. But it is a body they have developed and acquired by training days and nights since their youngest age, using the principle of not using strength.

They did not develop it by lifting rocks, climbing mountains or carrying branches. (Laughs) It is by relentlessly practising without strength that they developed such thick arms. And this is a truly remarkable work.

Developing such a body without using strength requires unbelievable amount of training. It’s generally something developed only by intensive practice started very early in life. Being born in a martial arts masters’ house, they practised all day while students came and went. At the time, after a day of training without using strength it occurred that my grandfather could not hold his chopsticks any more and needed someone to wrap his fingers around.”

My view is that technique over strength develops its own brand of strength, a purely utilitarian strength. Picture a 19th century blacksmith who earns his daily bread by heating and hammering metal all day, and has done so since he was a boy big enough to hold a hammer, the body fashions itself throughout the craftsman’s lifetime, no artifice, no vanity. I once saw a photograph of a generation of blacksmiths, father, son and grandson, standing proudly outside of the forge, meaty forearms folded across their broad cheats, proud of their labours with probably no concern about their bodies; these were certainly not the same as the contemporary tattooed, preening metrosexuals to be found propping up the bar in your local bistro. This was functional muscle.

With Kuroda’s antecedents it wasn’t the ‘hours’ spent in the Dojo, it was the ‘years’ of day to day training that made the difference.

But it is Kuroda’s description of relaxed strength, a nuanced strength that transforms the body almost by stealth, that caught my attention. He describes his grandfather’s handling of the sword as being ‘light’, but he also tells tales of his grandfather’s ability in cutting, even with a blunt sword!

The interviewer further pursues his theme of practicing with strength, asking, “Can or should beginners then practise with strength and power?”

The answer is:

“In absolute terms, it is not really a problem that they practise like this. But by doing so, it is very difficult to evolve and progress to another practice. In an era where we have less and less time, and where we can only allocate a few hours per week or month, it is impossible to enter another dimension of practice by training like that.

This is why I teach the superior principles to my students, from the beginning. I also require them to absolutely practise without using strength. If we use strength, we are directly in a very limited work. By receiving these teachings from the beginning, it is normal to put them straight into application”.

Effectively he is trying to square the circle of people not having the time to train as people did in the old days but still needing to reach to the higher levels of attainment. The ‘strength’ issue just side-tracks the development. His attitude seems to be to introduce people to the importance of the core principles first, because at least then they can start to work it out with some element of time on their side.

He’s not against strength as such, I just think he’s very careful in his definitions, particularly about the application of strength.

Again, for me this rings bells. Thinking about my own early experiences of Wado, I am fairly sure the cart was placed before the horse, and then subsequently I had to spend an awful lot of time and effort deprogramming myself and learn to appreciate the importance of ‘principle’. To paraphrase a friend of mine, ‘We learned our karate back to front; we learned to punch and kick first and then we learned to use our body; it should have been the other way round!’ [1].

Newcomers to martial arts training, particularly men, have an image in their heads (and in their bodies) of what ‘strength’ looks and feels like. As an instructor, I have to try to unravel this fallacy, and even though they understand it in their heads it is stubbornly hard-wired into their bodies. With time and patience, it can be undone, but it takes a lot of dogged determination on the part of the instructor and the student to do it. Interestingly women do not seem so encumbered by this type of baggage; for me, this makes women easier to teach and gives them greater potential to fast-track their development.

I am certain that there is much more mileage in this area, but I think that Kuroda Sensei’s insights give us a glimpse into the past and the mindset of the Japanese martial artists of the old school.

Tim Shaw

Image of Kuroda Sensei, courtesy of; http://budoinjapantest.blogspot.com/2013/11/kuroda-tetsuzan.html

[1] He won’t mind me mentioning him, but credit for this comment goes to the irrepressible Mark Gallagher. Once met, never forgotten.

Of Students and Teachers.

Luohan, courtesy of V&A.

There has been a lot of discussion about what makes a good teacher or a good Sensei; and people have found value in preparing and training the new generation of teachers/Sensei; and rightly so.

But I have a feeling that maybe we need to also look at it the other way round and perhaps teach people to be good students?

We typically think of our students as the raw material; the clay from which we mold and create; the blank slate to be written upon. Oh, we nod politely towards the idea that not all students come to us as equals; but then proceed to blithely continue on as if the opposite were true.

Can we teach people to be good students?

Well maybe…

But first we have to think that this cuts both ways. For are we not also students? Or at least we should be. We as teachers should lead by example as ‘life long learners’. As a teacher, never underestimate the student’s ability to put you under the microscope and observe how you learn and take on new material. So, while I pursue my theme, I have to cast a glance over my own shoulder.

At this point I feel I have to mention my own (additional) credentials in the area of teaching and learning, having recently retired after thirty-six years of teaching in UK secondary schools. Some of that experience boils down to very simple principles; key among these is that you are engaged with an unwritten two-way contract, or at least that’s the way it should work; the teacher gives and the student gratefully receives, in an active way (students also teach you!). Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work that way because one side of this contract sometimes welches on the deal; either actively or passively. The contract states that from the teacher’s perspective you are not doing your job if the student who walks into the room at the beginning of a lesson is the same person who walks out at the end. Something positive should have happened that results in the student growing – admittedly it might be small; it might be cumulative, but it is still growth.

Of course, this is very simplistic and there are many other factors involved. As in the Dojo, the environment has to be right to build an atmosphere conducive to development, with a positive encouragement of challenge and change; but not in a coddling bubble-wrapped way. I am reminded of commentator and thinker Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s idea of ‘Antifragile’, put briefly the concept that systems, businesses (and people) should aim towards increasing their capability to thrive by embracing stressors such as, mistakes, faults, attacks, destabilisers, noise, disruptions etc. in an active way. The antithesis of this is ‘resilience’. Resilience will protect you to some degree but it is not enough, it’s just a shell, potentially brittle, that given enough time and pressure is eventually breached.

Here is my personal take on what I think are the prerequisites of a good student:

- Empty your cup.

- Pay attention – martial artist Ellis Amdur says that progression in the martial arts is easy, all you have to do is listen. I am reminded of that very human inclination when involved in discussion; sometimes what we do when listening to someone is to fixate on one thing they have said, work out our own counter-argument in our heads while failing to listen to the rest of what they have to say. I have seen this with students in seminars, where the student asks the Sensei a question that they already know the answer to. At one level they are just looking to have their ideas endorsed, at another level they want everyone to see how clever they are – not the right place to ask a question from.

- Linked to the above; Open-mindedness. Nothing is off the table, but everything in its right place and in the right proportion.

- Understand that knowledge is a process that is ongoing; the sum of what you know is infinitely outweighed by the sum of what you don’t know. There is no end point to this.

- Self-discovery is more valuable to you than having something laid out on a plate for you. The things you achieve through your own sweat, pain and frustration you will hold as your dearest discoveries. I have seen times where a really, really valuable piece of information has been given to student and because it came so easily they dismissed it as a trifle.

- Leave your baggage behind. You may have had a lousy day at work, a fight with your partner, your kids have been ‘challenging’, but, check all of that at the door, you are bigger than the burdens you have to carry. Acknowledge that they are there but put everything in its right place. Personally, I found that troubles shrink after two hours of escape in the Dojo; distance gives you perspective.

- Avoid second-thinking the process; or, transposing your underdeveloped thinking on top of something that already exists. A blank slate is always easier to work with. I once spoke with a university Law professor who said he personally preferred the undergraduates to enter his course without having done A Level Law, he preferred the ‘blank slate’.

- Avoid making excuses in challenging situations. Nothing damages the soul more profoundly than realising that in fooling others you are often lying to yourself; it’s a stain that is really difficult to wash off. If you fail, fail heroically; fail while trying to give it your very, very best. That style of ‘failure’ has more currency than actually succeeding; not just from the perspective of others, but also from your own perspective.

- Put the time in! The magic does not only happen when Sensei is in the room. Get disciplined, get driven. Movement guru Ido Portal probably takes it to the furthest extreme by saying, ‘Upgrade your passion into an obsession’, that’s probably a bit heavy for some people, because obsessive individuals tend to be overly self-absorbed, and as such cut other people out of their lives. Whatever passion/obsession you have it is far richer when you bring other people along with you. Other people add fuel to your fire, and the other way round.

The list could go on, because teaching and learning are complex matters, much bigger than I could ever write down here. And besides… what do I know?

Tim Shaw

Thoughts on communicating with your own body.

In our training as martial artists we are taught ‘disciplines’, but are we taught how to get in touch with our own bodies?

As part of this we may ask the question, how do instructors teach people to move? How do they help the students to have a conversation with their own bodies?

In a way students are encouraged to have a shouting match with their own bodies – like that very English thing of trying to make yourself understood to someone who doesn’t understand English by just raising the volume; our internal voice is yelling at our bodies and the body just stands there literally dumbstruck.

Often the student wholeheartedly and with good grace buys into the whole teaching method associated with their system, with the assumption that everyone learns that way, it works for them, it will work for me, because I am supposed to have faith in the system… aren’t I?

The answer is, ‘no’, ‘no’ and ‘no’.

What should be happening is that a good teacher supplies doorways and access points for each individual student, because they are ‘individuals’.

However, we make an assumption that you know your own body, but this is far from the truth. ‘We know our own body like we know our own mind’, again, a false assumption. In the case of the mind, psychologists will tell you that you have much to gain from standing back and examining your own motives, noticing the times you lie to others, but more importantly, when you lie to yourself. ‘Tough Love’ administered to your own thoughts and motivation mechanisms is hard to do.

It’s the same with the body. You are only vaguely aware of your own somatic bad habits (unless someone points them out to you, like a well-meaning and observant instructor).

For example, problems with your posture, which then become the root cause of other problems, or when one muscle kicks in to take the load for another muscle, that should be taking the main load itself. Now, why is that muscle not doing its job? It might be transferring the strain from an area that is carrying a chronic weakness, an old injury, maybe one you are not even aware of! Consciously or unconsciously you protect the weakness as an ingrained habit and it’s not always in your interests to do so. Without expert advice you could well cause that part to become atrophied through under-work, thus compounding the problem.

On top of this, the human physical framework is a complicated system, and, as with all such complicated systems, you can’t move or adjust one part without it having an effect in other places, often the whole structure has to kick in to compensate for one small movement. I heard it said that even the action of raising a single eyelid has a micro-effect on the whole body.

However, you have to cope with one key reality – the body is a bodger!