otsuka

Wado on Film (Anything on film!) – Part 2.

Continued from part 1. What can we possibly gain from these ‘records’ of genius? How do we read the evidence presented to us?

What are we able to judge?

To return to the martial arts (and other arts).

Observing films on YouTube or other sources; shapes and patterns can only give us so much. It’s how we process the information that counts, but usually we cannot help but to attach our own baggage to it; this can cause its own problems.

To expand: If we look at the idea of works of art; it is said that it’s all about relationships:

- The relationship of the artist to their subject – think of landscapes or portraits. The artist must engage and interpret their personalised understanding of the subject.

- The relationship of the artist to their medium – this is the practical depiction of the theme and all of the technical aspects involved. This is the means by which the message is delivered.

- The relationship with the artist through their work to their audience.

Now, extend that to master Otsuka, (whether it is on film or a demonstration in front of an audience):

- His subject is his understanding of Japanese Budo.

- His medium is his performance – what he chooses to show is through the prism of his selected material, be that solo or paired kata or fundamentals.

- Then, ultimately, the connection/relationship between the ‘artefact’ as presented, and the viewer, the audience.

As with all of the above, clearly, the viewer has to be up to the task.

For a viewer in an art gallery, a Joshua Reynolds portrait from 1770 may present less of an intellectual challenge than a Jackson Pollock ‘Action Painting’ from 1948. The crisp clarity of Reynolds gives the viewer more to grasp on to than the mad, seemingly random, spatter of paint that Pollock applied to his canvases. But both have amazing value and depth (to my mind anyway).

It has been said to me on more than one occasion that those demonstrations that master Otsuka did in his later life were actually designed with a particular audience in mind; for the real aficionados, for those who really had the eyes to see what we mere mortals fail to see. They are not quite Jackson Pollock, this is perhaps where the metaphor is a little too far stretched, but sadly they still reside in an area above most of our pay grades.

To understand Otsuka (or Pollock) we would need to have considerable insight into the workings of the artist’s world combined with the ability to grasp the intangible.

With master Otsuka a good starting point would be to understand the world in which he lived, as well being prepared to ditch our western lenses, or at least be aware of how they colour our understanding of Japanese society and culture at that particular time. But even then, if we plunged headlong into that task, it would need to be supported by a huge amount of practical knowledge of Japanese Budo mechanics relevant to that particular stage in its development. You would be hard pressed to find anyone with those credentials.

The comparison with the visual artists and master Otsuka can also be exercised in this way: It is a sad fact that when we encounter an artist’s work in a gallery it is often in isolation; we seldom see the work as part of a continuum, instead it is a snapshot of their development at the particular time it was produced. There are very few examples in the art world where this development can be seen; the only one I can think of is the wonderful Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where it used to be possible to follow the artist’s development as a timeline; Van Gogh’s immature work looks clunky and uncultured, he’s finding his feet, he experiments with different styles (Japanese prints influenced, pointillism, etc) and then his work starts to blossom as it becomes more emotionally charged. What a pity he only worked for about ten years. My guess is that given more time he would have gone pure abstract, what a development that would have been!

What if?

To return to Nijinsky (from part 1) – what if a piece of film was discovered of Nijinsky dancing? What would a modern ballet dancer be able to gain; how would they judge it? Perhaps Nijinsky’s famous ‘gravity defying’ leaps would not look so impressive, in fact, compared to contemporary dancers he might look very ordinary. We will never know.

(Perhaps someone might comment that he has his hand out of position, or that he is looking in the wrong direction?)

But maybe the real power is in the myth of Nijinsky as another form of truth, which allows Nijinsky to become an inspiration, a talisman for modern dancers. [1]

For master Otsuka, as suggested above, the pity would be that his whole reputation and legacy should hang on hastily made judgements of those movies shot in later life.

But who knows; if he did have film of him performing when he was in his early 40’s (say from the mid 1930’s) perhaps he would have hated to have been judged by his movements and technique at that age? I would suggest that early 40’s would have put him at his physical prime, but not necessarily at his technical prime.

It’s a bit like the way great painters would hate to be judged by their early work. [2].

Like anything that is meant to be in a state of continual evolution, its early incarnations probably served some uses, however crude, but it’s never wise to stick around. Creatives like Otsuka weren’t going to allow the grass to grow under their feet. [3]

Anecdotes of Otsuka’s early days told by those close to him inform us that his fertile creativity was a restless reality; his mind was constantly in the Dojo. The truth of this comes from his insistence that Wado was not a finished entity, how can it ever be?

Conclusion.

I’m not saying that it is a completely pointless exercise. In writing this I am still working it out in my own head, trying to remind myself that we are still fortunate to have some form of connection to Otsuka Sensei, however tenuous, and how lucky we are to still have people around who bore witness to the great teacher, although, as we know, that will slip away from us so gradually that we will hardly notice it.

I have to remind myself that we are supposed to be part of a living tradition, a continuing stream of consciousness; a true embodiment of the physical form of what Richard Dawkins called a ‘meme’ [4]. This is why instructors take their responsibilities so seriously to ensure that Wado remains a ‘living tradition’, with emphasis on the ‘living’, not an empty husk of something that ‘used to be’. This is why I am reluctant to describe master Otsuka’s image as an ‘anchor’, because an anchor, by its very nature, impedes progress.

The best we can hope for from these ghostly moving pictures from the past is that they can be seen as some kind of inspirational touchstone. But, like the shadows in Plato’s Cave it would be a mistake to take them for the real thing [5].

Tim Shaw

[1] For anyone interested in Vaslav Nijinsky I recommend Lucy Moore’s book, ‘Nijinsky’. It tells an amazing story of an amazing man in an amazing age. Why nobody has made a movie about Diaghilev, the Ballets Russes and Nijinsky I will never know. I reckon Baz Luhrmann would do a fine job if he was ever let loose on the project.

[2] I have to acknowledge that in most competitive sporting fields the athlete is probably at his/her overall prime in their more youthful days. But, when looked at in the round, karate and other forms of Japanese Budo run to a different agenda. For me, and many others, sport karate is not the end product of what we do – it’s a by-product, an additional bonus for those who choose that path.

Look at the careers of dancers. I heard it said that dancers die twice. The first time happens when by injury or by more gradual natural debilitation they have to stop doing the one thing they love, thrive on and that their whole identity has been wrapped up in. The second time, is obvious. As this BBC article (and link to radio documentary) explains: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/1fkwdll6ZscvQtHMz4HCYYr/why-do-dancers-die-twice

[3] I know that am rather too fond of making references to jazz musician Miles Davis, but I have a memory of reports of Miles refusing to play music from his iconic ‘Kind of Blue’ album in his later years; he would say, ‘Man, those days are gone’ underlining his forever onwards trajectory – just as it should be.

[4] ‘Meme’ NOT the Internet’s interpretation of the word but, like a gene. However, instead of being biological, it refers to traditions passed down through cultural ideas, practices and symbols. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meme

[5] ‘Plato’s Cave’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allegory_of_the_cave

Otsuka picture source: http://www.dojoupdate.com/wado-ryu-karate/master-hironori-otsuka/

Wado on Film (Anything on film!) – Part 1.

On the surface it would appear that we are blessed to have so much film of the founder of Wado Ryu available to us. It is lucky that Otsuka Hironori was not camera shy and showed enough foresight to actually have himself recorded with the intention of securing the legacy of his techniques and ideas for future generations. I have heard that there is even more unseen material that has been archived away, held secure by his inheritors.

Although it is interesting that there seem to be zero examples of film of Otsuka Sensei as a younger man; while there are photographs a plenty. (Otsuka Sensei was born in 1892 and only passed away in 1982).

He appeared to hit his filmic stride in his mid-seventies. Although a while back, a tiny snippet of footage of the younger Otsuka did appear as almost an afterthought on a JKA Shotokan film. It was a bare couple of seconds, it certainly looked like him – he was demonstrating at some huge martial arts event in Japan; the year is uncertain, but I am guessing some time in the 1950’s. In this film there was an agility and celerity to his movements which is not so evident in his later years. [1]

Historically, it does seem odd that there is so little film available from those years of such a celebrated martial artist.

Ueshiba Morihei, the founder of Aikido has a film legacy that goes back to a significant and detailed movie shot in 1935 at the behest of the Asahi News company. Ueshiba was then a powerful 51-year-old, springing around like a human dynamo, it’s worth watching. [LINK]

On first viewing that particular film it left me scratching my head; initial examination told me that the techniques looked so fake. But the more I watched, there were individual moments where some strange things seemed to happen (at one point his Uke is propelled backwards like an electric shock had gone through him). At times Uke seems to attempt to second-guess him and finds himself spiralling almost out of control. Really interesting.

But for Wado, is this even important? Why does it matter? Afterall, Wado Ryu had already been launched across the world, much of which happened during Otsuka Sensei’s lifetime. Also, the first and second generation instructors were doing the best of a difficult job to channel Otsuka Sensei’s ideas.

So, what can we gain from watching flickering images of master Otsuka showing us the formalised kata or kihon? What value does it have?

I saw Otsuka Sensei in person in 1975. I watched in awe his demonstration on the floor of the National Sports Centre, Crystal Palace in London. I was only seventeen years old. I remember thinking at the time, ‘here is something very special going on in front of my eyes – I know that – but I can’t put my finger on exactly what it is’.

At that age and the particular stage of my development, I had very little to bring to the experience. I lacked the tools. Possibly the only advantage I had at that time was I was carrying no baggage, no preconceptions; maybe that is why the memory has stayed so clear in my mind [2].

Interestingly, Aikido founder master Ueshiba’s own students, in later interviews lamented that they wished they’d paid more attention to exactly what he was doing when he was demonstrating in front of them; even when he laid hands upon them, they still struggled to get it.

Can we ever hope to bridge the gap?

I think it is useful to acknowledge the problem. The reality is that we are THERE but NOT THERE; we are SEEING but not SEEING. I believe that we often lack the refined tools to understand what is really going on and what is really useful to us as developing martial artists. It comes down in part to that old ‘subjectivity’ versus ‘objectivity’ problem; can we ever be truly objective?

But it is the evanescence of the experience; it flickers and then it is gone and all we are left with is a vain attempt to grasp vapour. But isn’t that the essence of everything we do as martial artists?

To explain:

Two forms of artefact.

I read recently that in Japanese cultural circles they acknowledge that there are two forms of artefact; ones with permanence, solidity and material substance, and ones with no material substance, but both of equal value.

The first would include paintings, prints, ceramics and the creations of the iconic swordsmiths. For example, you can actually touch, hold, weigh, admire a 200 year old Mino ware ceramic bowl, or a blade made by Masamune in the early 14th century – if you are lucky enough. These are real objects made to last and to be a reflection of the artist’s search for perfection; they live on beyond the lifetime of their creator.

But the second, only loosely qualifies as an artefact as it has no material substance, or if it does it has a substance that is fleeting. This is part of the Japanese ‘Way of Art’ Geido.

There are many examples of this but the best ones are probably the Tea Ceremony (Sado) and Japanese Flower Arranging (Kado). Even the art of Japanese traditional theatre which is so culturally iconic actually leaves no lasting material artefact.

In the Tea Ceremony the art is in the process and the experience. Beloved of its practitioners is the phrase, ‘Ichi go, Ichi e’ which means ‘[this] one time, one place’.

The martial arts also leave no material permanence behind. Their longevity and survival are based upon their continued tradition (this is the meaning of ‘Ryu’ as a ‘stream’ or ‘tradition’, it seems to work better than ‘school’). The tradition manifests itself through the practitioners and their level of mastery; this is why transmission is so important. But a word of caution; the best traditions survive not in a state of atrophy, but as an evolving improving entity. It is all so very Darwinian. Species that fail to adapt to a changing environment and just keep chugging on and doing what they always do soon become extinct species.

Film (Nijinky, a case history).

Vaslav Nijinsky (1890 – 1950) was the greatest male ballet dancer of the 20th century. He was probably at his majestic peak around about 1912 as part of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. To his contemporaries Nijinsky was a God; he could do things other male dancers could only dream of; he danced on pointe and his leaps almost seemed to defy gravity. As this quote from the time tells us:

“An electric shock passed through the entire audience. Intoxicated, entranced, gasping for breath, we followed this superhuman being… the power, the featherweight lightness, the steel-like strength, the suppleness of his movements…”.

But, there was never any film made of this amazing dancer, so, all we have left are these words. Even though, at the time, movie-making was on the rise (D. W. Griffith was knocking out multiple movies in the USA in 1912 and earlier). At the time the dance establishment distrusted the new medium of moving pictures, they feared that it trivialised their art and turned it into a mere novelty; which clearly proved to be incredibly short-sighted.

If Nijinsky, arch-performer, had anything to teach the world of dance it is lost to us. Incidentally it is said that Nijinsky destroyed his mind through the discipline of his body. He ended his days in and out of asylums and mental hospitals.

We will never know how good Nijinsky was in comparison to modern dancers, or if it was all a big fuss about nothing. But then again, the very same could be said about any famous performer, sportsperson or martial artist born before the invention of moving pictures.

Other forms of recollections or records that act as witnesses.

A writer or composer leaves behind another form of record. For composers before the first sound recordings in 1860 it was in the form of published written music or score. We would assume that this would be enough to contain the genius of past musicians?

But maybe not.

Starting right at the very apex of musical genius, what about Mozart?

Well, maybe those written symphonies, operas etc. were not a faithful reflection of the great man? Certainly, there is some dispute about this. There has been a suggestion that rather like the plays of Shakespeare, all we have left are stage directions, (with Shakespeare the actors slotted in whatever words they thought were appropriate!).

We judge Mozart not only by todays orchestral/musical performances, but also by his completed score on the page, and some may see these pages as a distillation of Mozart’s genius; but perhaps Mozart’s real genius was expressed through something we would never see written down, thus, today, never performed? This was his ability to improvise and elaborate around a stripped-back musical framework. It is reported that he was able to weave his magic spontaneously. As an example, Mozart was known to only write the violin parts for a new premier performance, allowing the piano parts, which he was to play, to come straight out of his head. We have no idea how he did it, or what it might have sounded like.

More on this developing theme in the second part. What point is there to all this chasing of shadows? Are we kidding ourselves? Can we be truly objective to what we are seeing?

Part 2 coming shortly.

Tim Shaw

[1] If anyone is able to track down this piece of film, I would be grateful if they would let me know the URL. It seems to have disappeared from YouTube, or my search skills are not what they used to be.

[2] This was the same year as the IRA bomb scare, as well as Otsuka Sensei getting the back of his hand cut by his attacker’s sword.

Image of Nijinsky (detail). Nijinsky in ‘Les Orientales’ 1911. Image credit: https://www.russianartandculture.com/god-only-knows-tate-modern/

Martial Artists Past and Present.

What did the martial artists of the past have that we don’t have today?

I don’t think it is possible to give definitive answers to this question, but it’s worth asking the question anyway.

There are many amazing and literally unbelievable stories about martial arts masters from the past, and some of them not so very far distant from the current age. For example; is it true or even possible for Ueshiba Morihei founder of Aikido to willingly stand in front of a military firing squad at a distance of about seventy-five feet and, at the moment they pulled the trigger, some were swept off their feet and Ueshiba ended up miraculously standing behind them! And just to prove a point, he did it twice! Shioda Gozo, Aikido Sensei says he witnessed this. [1].

Some of the tales from the more distant history are just as amazing.

Even if we take these stories with an enormous pinch of salt, stripping away the propaganda and the myth building, surely, there’s no smoke without fire? Two percent of that kind of ability would be more than enough. They must have had something?

It has to be said that the background to these kinds of stories is presented to us in a landscape that is so very remote from our own.

I suppose a key question is; is it possible for someone in the modern age, living a 21st century lifestyle to achieve anything like the semi-miraculous skills of the likes of Ueshiba Morihei in Japan, or Yang Luchan (patriarch the Yang school of Tai Chi) in China. Logically, if such skills exist, it may well be possible to attain such abilities in the current age, but it is weighed down with an almost unsurmountable number of negatives.

Allow me to present a speculative list of advantages these historical superheroes may have had in their favour, and then run a few comparisons.

But there are some significant challenges; beginning with the task of imagining yourself in the cultural landscape of the far east maybe a hundred years ago or even further back. This is a tough call for Westerners, as we have to peel away our own cultural understandings and inhabit the mindset of people half a world away, existing on cultural accretions that sit upon thousands of years of history, but please bear with me.

First of all, I want to present you with a puzzle that would be a useful starting place:

The possibility of rapid development.

If we take Japanese Old School (Koryu) Budo as an example, and we understand that there existed a well-established stratum of advancement; traditionally acknowledged by the presentation of sequence of certificates and eventually ending with a certification scroll that acknowledged ‘Full Transmission’, i.e. mastery of the system. That in itself could be considered a grand statement with a massive responsibility sitting on the shoulders of the recipient, the expectations are enormous, surely?

But, researchers reveal that these scrolls of ‘full transmission’ were sometimes offered to individuals with only a couple of decades of practice! I refer anyone who doubts this to Ellis Amdur’s book ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’. You have to ask yourself, how is that even possible?

In the recent ‘Shu Ha Ri’ lectures (mentioned in my blog post ‘Budo and Morality’) old time Aikidoka George Ledyard, when talking about the abilities of modern Aikido people (comparable to Ueshiba) poured cold water on an argument often brought forward in Aikido circles that if you train long enough, eventually you will ‘get it’ (something I have also heard said in Wado). In the interview Ledyard clearly called bullshit on that argument; to paraphrase; he said that they’ve had Aikido in the USA for over fifty years and still nobody can do ‘it’! I am going to be careful here as to what constitutes ‘it’. I’m not talking about fireballs of Chi emanating from fingertips; just effortless mastery and control is enough.

So, what is so very different? Let me put a few conjectural musings before you, in no particular order.

Proliferation.

In Japan in the 19th and early 20th century a huge number of mostly young men studied some form of martial art (it became part of the school system). These arts had evolved into a commodity with a price. Previously the martial arts were the domain of the warrior class, now, because of the abolition of this same class, out of work warriors found a niche living teaching anyone who would pay. (A good example of this is found in the detailed ledgers of lessons taught and fees charged by Ueshiba’s Daito Ryu teacher Takeda Sokaku.)

There was an awful lot of it about.

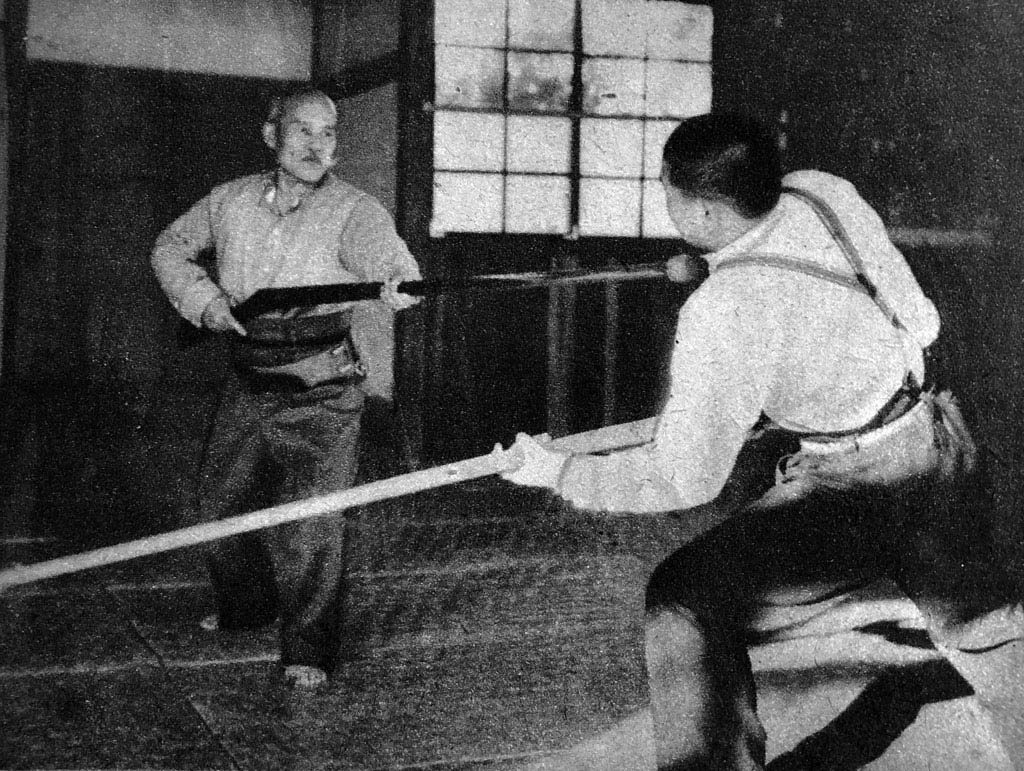

As a snapshot of the time; in his key formative years (pre Wado) the founder of Wado Ryu Karate-Do, Otsuka Sensei is said to have extensively sampled the huge proliferation of Dojo within a small area of Tokyo.

I think it is fair to assume that within this system there must have been a highly competitive filtration mechanism at work and it must have been very rough and tumble. To illustrate this point you have to wonder why it was that Otsuka Sensei would consider making a living out of treating predominantly martial arts related injuries? (At one point, Otsuka believed that this was an area worthy of supplying him with an income, but his teaching successes ultimately changed his trajectory).

Sanctioned Practice.

While it is apparent that the weapon training aspect of traditional Japanese martial arts struggled to survive (Naginata as an art was kept alive by the skin of its teeth mainly through the stubbornness of a few single-minded female protagonists) the empty-handed specialisms were adopted and subsumed by the powerhouse of the developing culture of what was to become Kodokan Judo. Judo, of course had a USP of being a ‘safe’ competitive format (see my blogpost on ‘Sanitisation’) and a builder of character, very much in line with progressive ideas developing within Japan at that time.

Even before that happened martial arts were considered part of the culture, and the Japanese have always been big on their culture, with a high regard for the arts and crafts and a special place for the artisans, and, it could be argued that the martial arts teachers were ‘artisans’. It may not be what an aspiring Japanese mother of the early Meiji Era might want for her son, but it still had the potential to provide respect and some form of status.

Lifestyle.

Looking at ancestors, either ours in the west or the equivalent in the far east, and, taking into account their social constraints, aspirations, outlook, mobility and world view, their bandwidth was pretty limited, compared to ours.

Theoretically our particular ‘bandwidth’ is huge, or at least it should be. For us, it’s not just the Internet, it’s education and all manner of loftier aspirations (being told what we should aspire towards) all supported by modern mechanisms, the structural framework of the society we live in and how we are kept secure by infrastructures that protect us from harm and ensure we are healthy.

Well, that’s how it’s supposed to work, but very recently things have become, to say the least, ‘challenging’, which in a way has highlighted some of the flaws in our current system.

Research has shown that this arguably ‘widened’ bandwidth is causing an actual shortening of our attention span, resulting in us leaping from one stimulus to another; one item of clickbait, and yet more irresistible reaffirmations on social media to boost our feeling of worth. Critics say this is actually dumbing us down and even restricting our brain power [2].

In the modern age the pressures of work leave less time to pursue other activities. In terms of martial art training in the west, anyone who trains twice a week is doing well and has probably established a good balance. Three times a week and people may say you are hardcore, any more than that and you’d probably be classed as an obsessive.

But this is so incredibly lightweight compared to someone like Shotokan Sensei Kanzawa Hirokazu who’s university training included multiple training sessions in one day! Or the Uchi-Deshi; the live-in students of Ueshiba Morihei, who not only had their daily training but were sometimes woken up in the middle of the night to be tossed around the Dojo by Ueshiba Sensei.

In historical Japan discipline and dedication were parts of the fabric of society, as were the virtues of hard graft and perfection of character through whatever it was you chose to dedicate your time, or even your life to.

Physicality.

The physicality of the early martial arts protagonists came out of a different lifestyle; even more so in rural areas, they were said to have ‘farmer’s bodies’. Ueshiba was a big believer in the physical benefits of tough labouring on the land and used it as personal training. There was definitely a culture of physical conditioning in the Edo period martial artists, photographs of Judo’s Mifune Sensei as a young man show a very impressive sculptured physique. Otsuka Sensei was said to have been keen on strengthening his grip, though his attitude to knuckle conditioning was somewhat ambiguous.

And then there is the issue of diet… A traditional old style Japanese diet has got so much going for it. It doesn’t mean that they were living in a health food utopia; for example; because of certain farming practices involving the use of human waste, internal parasites were surprisingly common. However, even with that, compared to our heavy use of sugars, processed foods and dairy products, they were by and large pretty healthy.

Longevity.

This has been a particular interest of mine. To take as an example; if you look at the lifespans of senior practitioners of the arts that use as a USP their health promoting benefits, e. g. Tai Chi with associated Chi Gung, it’s not particularly impressive. I have tried to dig into this but the statistics are a nightmare, particularly when it comes to average lifespans, mainly because of a lack of reliable information and infant mortality stats messing up the metrics.

But examined broadly, it doesn’t look great. Even with extreme outliers like the miraculous Li Ching Yuen. He was a Chinese herbalist and martial artist who it is claimed was born in 1677 and only died in 1933, making him 256 years old! Look into the supposed facts around his life and it begins to appear slightly suspicious.

On more than one occasion I have heard Japanese Wado teachers mention that practices found in other named karate systems are guaranteed to shorten your life, and a cursory look at the available evidence from those systems seem to support that idea, but even that doesn’t really tell you the full story. It has been said that some Japanese Sensei who come to the west seem to suffer from the negative effects of the western diet. Similar things are actually happening inside Japan; with the import of western food trends causing medical conditions to develop that used to be rare in Japan. Obviously, something that needs more research.

The lottery that is longevity can be skewed in your favour, if you lead a lifestyle devoid of extremes, striving for moderation in all things, then you have a better chance at living to a great age, but that of course is in competition with your genetic inheritance. Aforementioned Kanazawa Hirokazu pushed his body incredibly hard as a young man, potentially inflicting much early cellular damage to his system, yet still lived to be 88 years old. Mind you, Kanazawa adapted his training later in life to be kinder to his body, and he took up Tai Chi. But maybe his whole family line were predisposed to good health and longevity?

Speculative conclusion.

There is no definitive conclusion, only speculation.

Try as I might, I struggled to find any statistics that indicated martial arts participation in the UK, never mind about world-wide. Besides, what does that even mean? What even counts as a ‘martial art’? It would be really interesting to compare it to martial arts participation in Japan in the opening years of the 20th century.

I think it’s a fair guess to assume that the preponderance of martial arts in Japan in those early days would ensure some kind of higher waterline than in the modern world (well, at least I hope so). If we take the seemingly fast-track roadway to ‘complete mastery’ in 19th and early 20th century Japan as a truism, then that surely supports the argument – they weren’t giving Menkyo Kaiden (full transmission) away with Cornflake box tops and there had to be something going on! [3]

It’s true that they didn’t have the level of information at their fingertips in those days that we do today – but surely, it’s not the information, it’s what you do with it that counts.

In the modern era we are becoming further and further detached from the generation of masters who could actually ‘do it’, and if there are people out there who are on that level then they are side-lined by popularism. I cite as a possible example, Kuroda Tetsuzan (‘Who?’ I hear you say. It is ironic that his sparse, minimalistic Wikipedia entry speaks volumes, without saying very much at all.)

I suppose it all boils down to; who in the modern age is prepared to go beyond the mere hobbyist level and dedicate time and effort into an in-depth study of the martial art, supported of course by a Sensei who really does know their stuff?

Tim Shaw

[1] ‘Invincible Warrior’ John Stevens 1997 Shambhala Publications, pages 61 to 62. Other sources (Shioda’s biography) tell the story in more detail and mention that the marksmen were armed with pistols. At a guess, this incident was pre-war, possibly in the 1930’s. Shioda inevitably questioned Ueshiba, asking him how he did it? Ueshiba’s answer was as mysterious as the acts themselves, but he seemed to suggest that he was able to slow time down. Both times, one man was swept off his feet; the first time it was the man who Ueshiba said had initiated the first shot; the second time it was the officer who gave the command.

[2] Numerous modern commentators have railed against the ‘dumbing down’ that is happening. Google, John Taylor Gatto or Andrew Keen, but there are many other examples that perhaps don’t contain political bias.

[3] I am aware that there is a political dimension to the Menkyo Kaiden, certainly as it appears in the contemporary scene, which to me makes perfect sense.

Image: Author’s own collection.

Irimi in Wado Karate.

I was recently teaching and explaining the concept of ‘Irimi’ within Wado on a Zoom training session. This post is meant in part to reinforce and extend that particular lesson.

Taken simply ‘Irimi’ is a Japanese Budo term which means to enter into your opponent’s space in order to defeat them. I once heard someone describe it as a ‘mad dash in towards the centre’, a good image to hold on to.

The concept of Irimi has been a part of Japanese Budo, armed and unarmed for a very long time and is inextricably wrapped up in issues of timing, distance, rhythm and ‘Initiative’ (‘Sen’). The founder of Wado Ryu, Otsuka Hironori would have understood this concept from the very early days of his training.

In Aikido, the founder, Ueshiba Morihei, thought it so important that he made it one of the cornerstones of his art. Ueshiba had gained experience in the concept of Irimi at the very start of his martial journey, even as early as his short military career, where he learned the importance of the ‘mad dash towards the centre’ in hand to hand bayonet training. Developments of this bayonet training (Jukendo) remained part of his personal repertoire, and can be seen in the iconic 1935 Asahi Newspaper film shot when Ueshiba was in his physical prime at the age of 51.

Ueshiba Morihei in military clothing, with bayonet, photographed for Shin Budo magazine March 1942.

Sometimes Irimi is seen as a sidestep in towards the opponent; this can be quite misleading. A more meaningful and sophisticated way of using Irimi is to understand it as moving in deeply to occupy your opponent’s space – he wants to dominate and abide in that space; it’s his territory; the centre of his operation; his physical and psychological core. The laws of physics say that two objects cannot occupy the same space at the same time; so your job is to turn this particular law on its head – you conquer time and space; not through anything supernatural, but instead by an orchestration of superior judgement, the right timing, the right distance and the right cadence all working together with determination and commitment.

In Wado there are multiple opportunities to operate and sharped Irimi; it is part of our refined art, for example by creating narrow corridors of access through positioning and reading your opponent’s intent. For this you need sharpened perception (Kan) and an acute awareness of the ebb and flow (Kake Hiki), which is clearly a part of the formal kumite of Wado Ryu.

Otsuka Hironori.

In my Zoom session I was teaching it specifically through the mechanics of Shuto Uke, starting with the slide into position and narrowing of the body to ‘sneak’ into the opponent’s centre. The body and the arm move in like a blade. If done correctly the point of contact becomes irresistible as the elbow of the blocking arm stymies the opponent’s attack without any harsh, angular clashing of force. This results in superior positioning and direct access into the opponent’s weak angle and the contact arm effortlessly slides into the inside line accessing the head/neck; all of this supported by kuzushi and together would have a devastating effect, following the dictum of ‘fatally compromising the opponent while putting yourself into a position of safety’.

Tim Shaw

An article by Ellis Amdur which partly inspired this post: https://aikidojournal.com/2016/05/06/irimi-by-ellis-amdur/

Book Review – ‘Shindo Yoshin Ryu, History and Technique.’ Tobin Threadgill and Shingo Ohgami.

Rumours about the appearance of this book circulated a long time ago, and so finally it is here.

For me it was well worth the wait. Although it is a weighty tome I found it difficult to leave alone and so now I am on my second reading.

The organisation of the book is neatly packaged with many excellent photographs, diagrams and images. It covers historical, theoretical and technical aspects of Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu and supplies very informative personal and anecdotal experiences of key figures within the Takamura ha Shindo Yoshin Ryu.

The history section immerses you into the complex world of what was to be called ‘Koryu’ Budo/Bujutsu and it easily dispels any myth, which usually come out of oversimplification. Piece by piece an image of Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu starts to appear out of the miasma of Japanese lineages. Facts collide with legend, which in turn throws up further questions, some of which are unlikely ever to be answered.

It is clear that Threadgill Sensei and the late Ohgami Sensei have been involved in significant on the ground research; chasing down leads and engaging with surviving descendants of some of the main SYR players involved in this complicated saga.

Throughout the complexities, the jigsaw images of evidence, anecdote and documentation SYR appears as a system that was buffeted by change, navigating around the powerhouse that was late 19th century, early 20th century Judo, which lured traditional Jujutsuka into a world of Randori and contest and away from their fuller curriculum. It also describes the ascent and descent of various SYR branches which echoed much of what was happening to the traditional martial arts of Japan in the Meiji to Showa periods of Japanese history.

Does this book have relevance to students of Wado karate?

It depends where you are on your journey in Wado. For history buffs like me it was like catnip. I couldn’t get enough. But also, although SYR and Wado are as different as cats and dogs their connection cannot be ignored and as such, a surprisingly large section was devoted to the founder of Wado Ryu, Otsuka Hironori.

I was impressed with the author’s approach to the potentially thorny issue of Otsuka Hironori’s role in all of this. This was dealt with in an even-handed and factual way with Otsuka Sensei reputation intact, perhaps even boosted. Throughout the book the authors acknowledge the huge contribution Otsuka Sensei had made to the survival of SYR, without really being aware of it. The irony of course being that at the age of 30 Otsuka Sensei left SYR behind to synthesise his accumulated Budo experiences into the formulation an entirely new entity, Wado Ryu Jujutsu Kempo. Thus, for a long time, SYR became a footnote in Wado history – but not any more.

It is clear that Wado enthusiasts were drawn by curiosity to the surviving SYR and this curiosity extended sufficiently to cause some of them to beat a path to the door of Takamura ha Shindo Yoshin Ryu Kaicho Tobin Threadgill Sensei – his recent seminars in Europe attest to that.

In the technical section of the book, although deliberately and understandably incomplete, it is possible to see common strategies and common nomenclature. Within the body of this section it is possible to read between the lines and gain glimpses of Otsuka Sensei’s technical base and the underlying strategies of Wado Ryu. My conversations and experiences of people within TSYR have certainly informed my reading of this text, reinforcing my view that when Wado was formed the baby was not thrown out with the bathwater.

Who knows, perhaps there is more to come from the pen of Threadgill Sensei. I certainly hope so.

I have it on good authority that the late Ohgami Sensei was able to see advance productions of this book and greatly approved of the completion of this joint project before his passing. Although I only met him once I know that he will be greatly missed.

Tim Shaw

What Master Otsuka Saw (Probably).

A presumptuous title, I know, but bear with me, I have a theory.

I have often wondered how Otsuka Hironori the founder of Wado Ryu thought. I wished I had been able to climb into his head, navigate all those very Japanese nuances that are so alien to the world I live in and see as he saw; a bit like in the movie ‘Being John Malkovich’. But more importantly and specifically to see what he saw when he was dealing with an opponent.

I am fairly convinced he didn’t see what we would see in the same circumstances, the mindset was probably very different.

This is all guesswork and speculation on my part but to perhaps support my claim, let me backtrack to a comment made by a very well-known Japanese Wado Sensei.

I was present when this particular Sensei made a very casual off-the-cuff comment about Otsuka Sensei – so quick and matter-of-fact it was easy to miss. It was in a conversation generally about movement; I can’t remember the exact words but my understanding was this; he said that Otsuka Sensei’s ‘zone’ was ‘movement’ – he (Otsuka Sensei) could work with ‘movement’, but inertia held no interest for him, it was no challenge. That was it; an almost throwaway comment.

I held on to this and thought about it for a long time, and out of this rumination I would put this theory forward:

It is highly possible that Otsuka Sensei was acutely tuned to zones of motion and energy; like vectors and forces governed by Intent and energised by Intent; an Intent that for him was readable.

For him it is possible that the encounter was made up of lines of motion which, in a calculated way, he chose to engage and mesh with. These involved arcs of energy that extended along lines limited by the physiology of the human frame (a refined understanding of distance and timing), but also he was able to engage with that frame in itself, not just its emanations and extensions. He saw it as Macro and Micro, as large or small scale tensions and weaknesses and he was able to have a dialogue with it, and all of this was happening at a visceral level.

The computations normally associated with reasoning and calculation would have just gotten in the way – no, this was another thing entirely; this was the ‘other’ brain at work, body orientated, woven into the fibre of his being, much more spontaneous, coming out of a cultured and trained body. And there is the catch… it would be a great thing to have the ability to ‘see’ those lines, energies and vectors, but ‘seeing’ on its own has no meaningful advantage; it becomes a self-limiting intellectual exercise; an academic dead-end. No, the body (your body) has to be trained to be refined in movement, otherwise the necessary engagement/connection is not going to happen; or, it happens in your head first and your body is too late to respond! The key to unlocking this is there, it always has been there; but unfortunately too often it is hobbled by formalism, or that perennial obsession of just making shapes.

It’s a lifetime’s work, and, even with the best will in the world, probably unobtainable. But why let that put you off?

Tim Shaw

Appraising Kata.

Re. Wado Kata performances on YouTube or forums, be they competition honed kata or personal kata movies. Comments are invited, but I really don’t understand what people want these comments to say?

Competition kata is… a performance, practiced to comply with a set of criteria so that one kata can be compared to another and clearly people look at examples of the kata online and match it off against their own personal expectations.

No kata is ‘perfect’, but if we notice flaws in the kata through the imperfect medium of video what kinds of flaws are we looking for?

Some people get all hung up on ‘a foot position there’ and ‘hand position elsewhere’ yet fail to see the bigger picture. I guess people will disagree with me here, but surely the bigger picture is the method of actually moving – and I don’t mean how fast or strong a technique is delivered; that would be a bonus – if the techniques are performed with the refined principles of Wado AND have celerity, energy and intent, yes that is probably going to be a damn good kata.

Surely we have come a long way from ‘harder, faster stronger’? Wado is a complex system – by that I mean ‘complex’ not complicated; there is a difference. One move, like Junzuki, can contain many complexities, while 36 kumite gata can become complicated – but not insurmountably so.

For me the curse of kata appraisal is what I call the ‘picture book approach’. In that some people judge the kata in a kind of ‘freeze frame’ of the end position of any individual move, taking that frozen image and judging it just by its shape. This method of judgement is really low on the evolutionary ladder. Since the 1960’s Wado has evolved significantly and students and instructors have access to a far greater level of understanding than they had fifty years ago, except of course for those areas where people have clearly opted for a policy of arrested development.

Then there is Observer Bias:

“Observer bias is the tendency to see what we expect to see, or what we want to see. When a researcher studies a certain group, they usually come to an experiment with prior knowledge and subjective feelings about the group being studied.”

People see what they want to see, because they are uncomfortable with anything that interrupts or contradicts their current world view – it’s human nature. Thus, when we feel a need to say whether this approach to kata is superior to that approach, maybe it’s just an expression of our own bias; we focus on those things that either comply with our world view, or don’t.

Judging by comments of forums regarding Wado kata, it also tends to bring about a worrying tendency towards tribalism. I fully understand this, and I am sure that at times I have also felt the knee-jerk inclination towards my own tribal instincts, but I try my best to keep these in check. However, as long as we recognise this for what it is, without the need to call it out, then it will hopefully wither on the vine and conversations will remain civilised and polite.

Then there comes the argument; is there such a thing as a bad kata? I would say; yes there is.

Some say that as long as they stay within a particular bandwidth that represents an acceptable understanding of Wado then that’s fine. But that’s just a fudge – exactly how wide is this bandwidth?

Is the bandwidth just about shapes? From my understanding Otsuka Sensei established some very sound guidelines and sent his best students out into the world with the responsibility to pass on these essential guidelines and although it may have been part of it, shape-making was not the main priority on the list.

Tim Shaw

Sanitisation.

Early 20c Japanese Jujutsu.

I recently watched a YouTube video which was focussed upon the sanitisation of old style Jujutsu techniques that were cleaned up to make them safe for competitive Judo. Throws and techniques which were originally designed to break limbs and annihilate the attacker in dramatic and brutal ways were changed to enable freeform Judo randori where protagonists could bounce back and keep the flow going.

This inspired me to review techniques in Wado, some of which I believe went through a similar process.

We know that the founder of Wado Ryu Karate, Otsuka Sensei had his origins in Koryu Jujutsu and that Wado was crafted out of this same Koryu base; Wado is certainly still considered as a continuation of the Japanese Budo tradition. Koryu Jujutsu in particular had historically developed a reputation as an antiquated form of brutality which was not compatible with an agenda developed by modernisers like the founder of Judo Kano Jigoro.

To set the context; Wado went through many transformations, and even though quite elderly Otsuka Sensei was still reforming and developing Wado Ryu throughout his long life; a project that was continued through subsequent generations of the Otsuka family.

But how much has Wado allowed itself to be sanitised? Did we lose something along the way? Was Wado de-fanged, did it have its claws clipped? And, if it has, where is the evidence?

But beyond that – does it matter? The loss of these dangerous aspects may well be a moot point; the development of Wado may well have bigger fishes to fry, and this particular issue may just be a distraction from a much larger agenda.

However, to my mind it’s still worth considering.

First of all, I am reminded of a discussion I had with another instructor regarding the craziness of the practice of the Tanto Dori. Thinking back to when these knife defence techniques were part of the Dan grading syllabus, nobody seemed to care what kind of blade you pulled out of your kit bag; blunted pieces of stick, to razor-sharp WW2 bayonets, in fact there seemed to be a badge of honour based upon how sharp and dangerous was your Tanto! We laughed about how such practices would be looked at in today’s politically correct, health and safety environment.

In Judo there are the Kinshi Waza, the banned techniques; these include. Kani Basami (Crab Claw scissors), Ashi Garami (Entangled leg lock), Do Jime (Trunk strangle), Kawazu Gake (One leg entanglement). These are the techniques that the authorities decided were more likely to cause injury, so not necessarily banned because of their viciousness, more their proclivity to cause accidental damage.

Within Wado undoubtedly some techniques were ‘cleaned up’, even within my time.

I can think of at least fifteen techniques, most of which existed inside the established paired kata which were ‘made safe’. Sometimes this came out of trial and error, i.e. the Japanese Sensei saw too much damage incurred by over-enthusiastic students, so decided to soften the technique to minimise injury. Others were implied techniques, e.g. ‘if this technique were to be taken through to this position it would result in significant damage’. Some of these techniques were hidden; you would struggle to spot them if they weren’t explained to you. In some cases the ‘brutal’ part of the technique was actually easier to execute than the so-called ‘cleaned up’ version, but this latter version remained closer to the practice of Wado principles; a contradiction….maybe, maybe not.

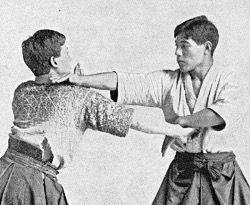

A variation on Kumite Gata. The body is ‘scissored’ apart; this is combined with a leg action that completely takes away the base. It is almost impossible to practice this technique safely.

I think that most people are aware that some throwing techniques were designed so that a successful breakfall (Ukemi) would be extremely difficult or even impossible, resulting in damage that you would never recover from; not something to dwell on lightly. (A prime example in Wado is the technique known as Kinu Katsugi, which we now practice in a way that enables uke to land relatively safely).

This Ohyo Gumite technique is very effective on its own, but another variation involving standing up from this position would result in Uke being dropped to the floor with very little chance of being able to protect themself.

Right, Suzuki Sensei showing the ‘stand up’ associated with this technique.*

There are other Wado techniques which on the outside look incredibly dangerous but are sometimes so wrapped up in misunderstood formalism that the accepted coup de grace becomes a merely academic endeavour (works well on paper but could you make it do the job?). Usually this is because of a misunderstanding of the mechanism of the technique itself, or the mechanism of ‘kata’ and how the teaching model actually functions.

I remember Suzuki Sensei sometimes held ‘closed-door’ sessions, you had to be above a certain grade to participate and no spectators were allowed. I attended some of these and the best I can describe them was that they involved what some would think of as ‘dirty tricks’, but very effective fighting techniques which would really damage your opponent.

To reiterate; while it is interesting to speculate on these matters, compared to the other complexities of Wado they could be looked upon as a mere side-show, after all, just the fundamentals take a lifetime to get your head round, never mind all of this.

Tim Shaw

*Photo credit, Pelham Books Ltd, ‘Karate-Do’, Tatsuo Suzuki 1967.

A Few Notes on Nagashizuki.

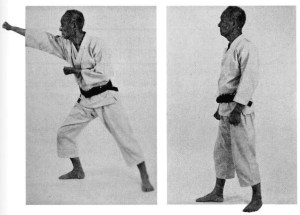

Otsuka Sensei performing Tobikomizuki.

Without a doubt nagashizuki is a hallmark technique of Wado karate; it is also one of the most difficult to teach.

In other styles of karate I have only ever seen techniques that hint at an application that could loosely fall into the area of nagashizuki, with a very rudimentary nod towards something that could be categorised as Taisabaki, but at risk of contradiction nagashizuki in karate is pretty much unique to Wado.

But there is so much to say about nagashizuki as it features in the Wado curriculum as it helps to define what we do.

If you were to explain nagashizuki to another martial artist who has no knowledge of Wado, you could describe it as being very much characteristic of Wado as a style; a technique pared to the bone, without any frills or extra movements. Done properly it is like being on the knife-edge, it is brinksmanship taken to the extreme. I have heard a much used phrase that to my mind gives a picture of the character of nagashizuki, as follows:

‘If he cuts my cloth I cut his skin. If he cuts my skin I cut his bone’.*

Here is a technique that flirts with danger and requires a single-minded, razor sharp commitment, with serious consequences at stake.

Technically, there are so many things that can go wrong with this technique at so many levels. In an active scenario you have to have supreme courage to plunge directly into the line of fire, the timing is devastating if you get it right. Many years ago it was my go-to technique when fighting people outside of Wado, particularly those who took an aggressive line of attack hoping to drive forward and keep you in defensive mode. But I also found out that this technique had added extras, which you must be aware of if you use it in fighting; one of which is the devastating effect of the strike angle.

On two occasions I can think of, to my shame, I knocked opponents unconscious with nagashizuki. When delivered at jodan level the strike comes in from low down, almost underneath the opponent and its angle is such that it will connect with the underneath and side of the jaw. As I found out, it doesn’t need much force to deliver a shockwave to the brain, and, if the opponent is storming in, they supply a significant amount of the impact themselves – they run onto it.

This last point about forward momentum and clashing forces illustrates one of the oddities of the way the energy is delivered through the arm. A standing punch generally has to have some form of preparatory action (chambering), depending where it is coming from; nagashizuki when taught in kihon is deliberately delivered from a ‘natural’ position, and as such the arms should just lift as directly and naturally as possible into the fulling extended punch – my favoured teaching phrase for that is, ‘like raising your arm to put on a light switch’, that’s it. The arm itself acts as a conduit for a relay of connected energy generators that channel through the skeletal and muscular system into and beyond the point of delivery.

This is where further things can go wrong; the energy can be hijacked by an over-emphasis on the arm muscles or the ‘Intent’ to punch. Don’t get me wrong, ‘Intent’ can be a good thing, but when it dominates your technique to such a degree that it becomes a hindrance this can cause all kinds of problems.

The building blocks to nagashizuki could be said to begin with junzuki, then on to junzuki-no-tsukomi and then to tobikomizuki and finally to nagashizuki. Lessons learned properly at each of those stages gives you all the information you need, but it is important to go back to those earlier lessons as well. Junzuki-no-tsukomi for its structure is the template for your nagashizuki, but not just for its static position, but how it is delivered through motion; it is an amplified version of things you learned in junzuki – it is junzuki with the volume turned up.

Nagashizuki is a good technique to pressure-test; from a straight punch (at any level) to a maegeri, even to a descending bokken; this is very useful because it emphasises the slipping/yielding side of the technique; a very determined extension of one half of the body is augmented by a very sharpened retraction of the other half, the movements feed off each other, but essentially they are One. In fact everything is One, in that wonderful Wado way. And here is the conundrum that we all have to face when doing Wado technique; you always have a huge agenda of items that make up one single technique BUT…. They all have to be done AS ONE.

Good luck

Tim Shaw

*I am reminded of a line from the 1987 movie ‘The Untouchables’, where the Sean Connery character says, “If he sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue”.

Principles.

In another posting I mentioned the importance in Wado karate of focussing on Principles. Here I am going to present another angle to maybe supply a slightly different perspective.

Principles are not techniques; they are the essence that underpins the techniques. These work like sets of universal rules that are found within the Ryu. Don’t get me wrong these are not simple; they work at different levels and in different spheres. An example would be how these Principles relate to movement. There is a hallmark way of Wado movement; something that should be instilled into all levels of practice, from Kihon and beyond. If in a Wado training environment technique is prioritised at the expense of Principles of movement then students are learning their stuff back to front. The technique will only deliver at a superficial level; the backbone of the technique is missing.

This is where I think that learning a huge catalogue of techniques in itself is of limited application, and particularly mixing and matching techniques from other systems; it may work but only to a certain level. To me personally this approach lacks ambition and has a limited shelf life.

The underpinning Principles are not modern inventions, they originate way back in in early days of Japanese Budo and were forged in a very Darwinian way. These were created and adapted at the point of a sword by men who witnessed violence and blood; these things were deadly serious, no delusion, no fantasy, instead sharp reality. Those days are gone but the Principles stretch forward into the future, but they are vulnerable and the threads can easily be broken, we ignore them at our peril. It sounds dramatic, but in a way we are the custodians of a very fragile legacy.

If we look at the life of the first Grandmaster of Wado Ryu, Ohtsuka Hironori, it could be said that he had one foot in the past and one foot in the future. There is a connection between him and the men of the sword who experienced the smell of blood, particularly his great-uncle Ebashi Chojiro who we are lead to believe experienced the reality of warfare probably in the Boshin Senso (but that needs to be confirmed by someone more knowledgeable than me.). Traditional martial arts supply a direct line into the past and their values come from concepts that underpin Japanese Budo of which Wado is part.

Principle is the key that unlocks multiple opportunities and techniques. This works surprisingly well. The human psycho-physical capability is amazingly sophisticated. I have often come across students asking about the problem of learning techniques on both sides. My reply is that personally I have had no trouble switching from one side to the other. I remember hearing about sleight of hand magicians who have to learn a piece of complex manipulation with one hand and spend hours and hours of laboriously practice (and failure) to master the trick. But if the one-handed trick was to be switched to the other hand then the learning time was dramatically decreased. This is an aspect of body memory and it is not to be underestimated, it is complex, multi-faceted and amazingly fast when compared to a more calculated thought-based approach.

Tim Shaw