martialarts

Is Wado really a style of Karate?

I am publishing this post on here as an example of the more focussed articles I have lined up for the Substack project. My postings on Substack will eventually be on two levels; free content that comes out every week and content that can be accessed by a small paid monthly subscription, believe me, it will be worth it. If you haven’t already, sign up free for the project at, https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

Btw. If you are signed up and on Gmail, be wary that it has a habit of dropping Substack posts into the ‘Promotions’ folder.

On with the theme.

Everything has to fit into some kind of category; labels must be attached and pigeonholes have to be filled – otherwise how do we know what we are describing. It is a quick way to make sense of things, particularly if we want to communicate to other people what we are talking about.

The quick shorthand operates largely because we are in a hurry – someone asks, “What do you do with your evenings?”, answer, “I go to my karate class”. The conversation could end at that point, or the questioner might ask for more information, out of politeness or maybe they are genuinely interested. And that is your opportunity to volunteer more detail.

Do we want Wado to be called ‘karate’?

But we Wado people are likely to be entirely happy to allow what we do to be identified as ‘karate’. But, is Wado Ryu/Kai etc really karate? Maybe it is something else which has not been truly pinned down, like a newly discovered genus; a wild critter that is neither ‘dog’ nor ‘cat’, a kind of Tasmanian Tiger, but still kicking around, possibly even thriving? [1]

It is entirely possible that Wado sails under a flag of convenience? I have cousins who hold both US and UK citizenship and I can’t help noticing that when they are in the UK they fly the US flag and when in the USA they fly the British flag when it suits them (really noticeable when the accents change). With Wado it very much the same; being identified as ‘karate’ has opened many doors for them, but what about its other possible identifying qualities, what are the competing factions?

Let me try and lay out the case… with some provisos, I am not Japanese and I run the risk of looking at this from a very western viewpoint, so everything here is conjecture and opinion.

Let me start with the easy one:

Wado as Japanese Budo.

This is where we apply the national pride and cultural credentials to Wado. It has such deep roots that to explain it would be like trying to untangle spaghetti. This is the bigger ‘identity’ issue. ‘But Wado was only recognised as an entity in 1938’! – I hear you say. Maybe, but, as we will see, the complexity of the history of Japan’s own indigenous martial systems is not to be taken lightly, particularly as it applies to Wado.

Personally, I quite like the ‘Wado is a distinct form of very Japanese Budo’ angle; it ties it neatly to the unquestioning high cultural and moral characteristics of anything that falls into the category ‘Budo’. But, as we know ‘Budo’ is a broad grouping and can be annoyingly difficult to pin down, especially when it uses high-minded and sometimes vague terms in which to describe itself.

But the subtext here should not be skipped over too quickly – ‘distinctly Japanese’, we are now talking about Budo as a kind of cultural artefact, one that has to be wrapped in the flag. But ‘distinct from’ what?

Historically, indigenous Japanese arts have had their heyday, and since Japan took to embracing all things western, these ‘arts’ slipped in the category of anachronisms; they were considered out of step with the direction Japan saw itself going in. For industrial Japan there was no going back, and, it has to be said, the Japanese performed economic and technical miracles; certainly, pre WW2, where things then went more than a little sideways.

Then came a time when these ancient arts needed to either be rescued from decline or completely resurrected, and, in the marketplace for oriental martial arts they had to stand up for themselves and proclaim who they were. This ‘claiming of the national identity’ came a lot earlier than most people think; it could be said that ‘karate’ was the first skirmish in a culture war that was yet to happen.

To keep this brief; Karate was from Okinawa, with very strong cultural ties to China, one of the earlier incarnations of the characters used to write ‘karate’ was actually ‘Chinese Hand’, so effectively this was an imported system and, considering the rocky historical relationship between China and Japan (which was to get a whole lot worse before it got better), this was not a welcome import in conservative eyes. (This all happened around 1922 and, if you’d asked someone in a Tokyo street prior to that date about ‘karate’, they’d say they’d never heard of it, it only existed in the Okinawan islands [2])

‘Karate’ had to have an image make-over to make it palatable. Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado, was a key mover in this area. He (and others) helped to make the necessary adjustments and secure karate in Japan as something the establishment would welcome.

Otsuka Hironori Sensei managed to eventually unshackle himself from the Okinawan karate system that he had previously been so eager to embrace (whether by accident, fortune or design is open to speculation) and from that base and his martial cultural roots in Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, he was able to craft something new, something distinctive, and was entirely happy to describe it as ‘Japanese Budo’ (while still holding on to the ‘karate’ moniker).

Ducks and Zebras.

‘If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck and looks like a duck…it’s a duck’. Take a quick look at the qualities that the casual observer would see in Wado karate, a kind of comparative checklist; what is it you find in most styles of karate?

- An emphasis on punching, kicking and striking; which lends itself well to a sport format.

- A training regime which includes solo kata, which all follow a similar external structure and hold on to original names which define their Okinawan origins.

- A training uniform that would not be out of place in any karate Dojo in any style in the world.

Bear with me on this one; the saying, ‘When you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras’. This is told to trainee doctors, reminding them to think when diagnosing, of the most common, hence the most obvious answer. But I recently heard a doctor explaining how this idea was of limited use and how she had once misdiagnosed a patient suffering from a rare condition. Is Wado perhaps the zebra?

Take another look at the above checklist; all but the second point can be explained away; firstly, striking and kicking are not unique to karate. Secondly, it was Otsuka who was one of the main movers in pushing towards a sport format [3]. And thirdly; the uniform (Keikogi) was just a convenient design development that happened over decades, which was inevitable really.

Point 2 has been chewed over a lot by karate people, both Wado and non-Wado, but I will offer my view in a nutshell. Otsuka saw something in the karate kata that he could use. What he wanted was a framework, no need to reinvent the wheel. What was really clever was that he transposed his own ideas on top of that framework, which, interestingly, was hugely at odds with how the other karate schools/styles used it.

Wado as Jujutsu.

Why would that even be considered?

Evidence?

The second grandmaster of Wado Ryu Otsuka Hironori II at some point decided to re-register the name of his school with the authorities (probably the Dai Nippon Butokukai) and call it ‘Wado Ryu Jujutsu Kempo’. So ‘karate’ was dropped completely and ‘Jujutsu’ was added. I am not going to second guess or explain the reason for this, I am not Japanese and I am not versed in the Japanese martial arts political world, but I will speculatively introduce a few thoughts from a very western perspective (always dangerous).

Firstly, apply a similar checklist to the one above, but for Jujutsu, and, from a casual lazy western perspective, nothing stacks up.

The first grandmaster and creator did indeed add a catalogue of standard Judo/Jujutsu techniques to the original list he had to present to the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938, but these were largely dropped (the exceptions being the Idori and the Tanto Dori). But, my observations tell me that it would be a mistake to assume that this is all there is to traditional Japanese Jujutsu, the complexity goes much further than Jujutsu tricks [4].

What about the word ‘Kempo’ (or ‘Kenpo’). Actually, this has a long history in Japanese martial arts.

The term Jujutsu did not really exist as a distinct entity in Japan until the early 17th century, before that a whole bunch of other terms were used; kumiuchi, yawara, taijutsu, kogusoku and kempo. ‘Kempo’ is just the Japanese version of the Chinese Chuan Fa, or ‘Fist Way’. This does not mean that Kempo is from Chinese boxing, that is a rabbit hole not worth going down. There is however a strong link with the striking aspect of Old School Japanese martial traditions, often associated with Atemi Waza, the art of attacking anatomical weak points with both hand and foot. There is a suggestion that Otsuka Sensei was really skilled at this prior to his first exposure to Okinawan karate and that his first Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu teacher, Nakayama Tatsusaburo was somewhat of on an expert in this field.

A conversation with someone closer to the source also suggested that the word ‘Kempo’ had been around earlier in the history of the formulation of the distinct identity of Wado, but I have been unable to verify this with documented evidence.

All of this tips the scales in favour of the inclusion of the word ‘Kempo’, but, this is just my opinion, there has to be more to it than that, there always is.

One more piece of evidence to muddy the water.

When master Otsuka had to register his school with the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938 he officially recognised one Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki the semi-mythical founder of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu as the founder of Wado Ryu, rather than himself. This might not be as unusual or controversial as it sounds. Firstly, there is the Okinawan/Japanese problem, so this is a smart political way of painting Wado in the right colour to be accepted in the highly conservative establishment of the Butokukai. But, Otsuka Sensei himself explained this point; saying that, because the actual ‘founder’ of karate was unknown, his best option was to name Akiyama. [5] The suggestion being, I suppose, that the Yoshin Ryu (SYR) component of Otsuka’s new synthesis was significant enough to make this entirely permissible.

There is also an historical precedent, well in theory anyway, this is to do with one of the early branches of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, not so very far removed from Otsuka Sensei’s root art of Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu.

In the 1700’s one Oi Senbei Hirotomi seems to have picked up the reins of what was established as ‘Aikiyama Yoshin Ryu’; a theory goes that in his efforts to claim a direct lineage for his curriculum he also used the Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki name in a more blatant way than just applying it to the signboard of his school, he used his name as official founder. This may have been to deflect attention away from any thoughts that his own teachings were a blend of other influences by actually saying that Akiyama was the real founder of the Ryu not Oi Senbei! Was this done out of modesty or deception? Was it even true? Who knows. It is one those mysteries that will never be answered.

Ellis Amdur puts other theories forward, suggesting that by placing a semi-mythical person as figurehead you create space to allow your new development/style/school to stand on its own feet and to become established without the glare of unnecessary criticism or accusations of immodesty. Is this perhaps in part, what Otsuka Sensei was doing. [6]

In conclusion, just what is Wado? New species, sub species, synthesis or something that defies categorisation? And, the final question; does it even matter?

Tim Shaw

[1] Tasmanian Tiger (extinct 1936), it looks like a skinny wolf, but it has stripes down its back like a tiger; in fact it was a kind of carnivorous marsupial.

[2] If you said ‘Kempo’ you might get a glimmer of recognition.

[3] Wado wants to play in the ‘sport/competition’ sandpit? Call it ‘karate’ and the door opens, it’s all very clever politically.

[4] At the time many of the listed techniques were common knowledge, even to schoolchildren, but that doesn’t make them any less difficult.

[5] Source; ‘Karate Wadoryu – from Japan to the West’ Ben Pollock 2020. An excellent resource. Who in turn drew his reference from, ‘Karate-Do Volume 1’ Hironori Otsuka 1970.

[6] Source ‘Old School’ Ellis Amdur and further commentary from Mr Amdur at https://kogenbudo.org/how-many-generations-does-it-take-to-create-a-ryuha/

Books for martial artists. Part 1. Lost in translation.

A two-part martial arts journey into where ‘extra reading’ can take you.

It’s only natural for us to want to boost our martial arts learning by reading around the subject, or tracking down published material that in some way gives us hints as to how to focus and direct our lives in a manner worthy of the Budo ideal.

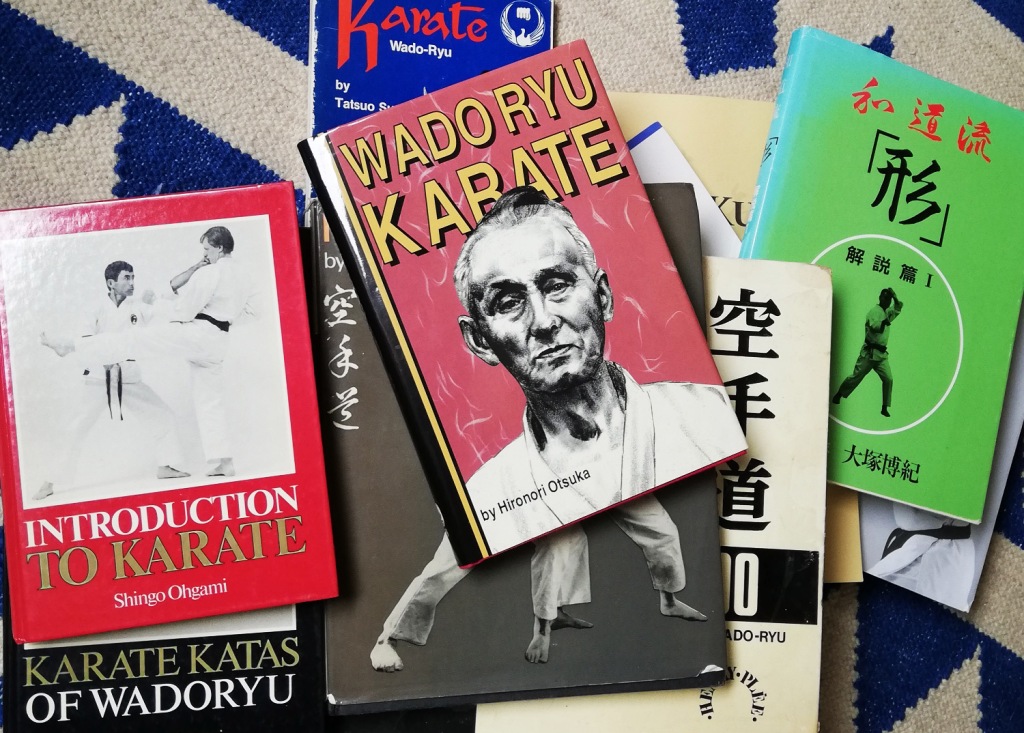

In a previous blog post (‘Why are there so few books on Wado karate?’) I was puzzling over the fact that there are very few written sources specifically dedicated to Wado. But what about the general reader who might want to dig into history, culture or how things operate in other systems?

Publications originating in the far east.

Like everyone else, I have found myself drawn towards written material from Japan or China, with a particular fascination with the really early stuff. But of course, I have had to make do with English translations.

However, experience has taught me to be wary of these translations, as so much can be lost or completely twisted out of shape.

Here are the main problems:

- Bad translations either written with the translator’s bias, a political agenda, the translator’s preconceived ideas, the translator looking at the text through modern lenses, the translator being a non-martial artist, thus not understanding specialised language, etc.

- Misunderstandings; e.g. kanji or old style Chinese characters being badly copied [1], or so outdated as to be almost unintelligible without HIGHLY specialised knowledge.

- Things taken out of context, e.g. their historical context, or cultural context.

- Deliberate obfuscation – text written in a way that only the initiated can understand them.

Of all of the above I think it is the ‘taken out of context’ that is the biggest error. The further back in history you go the more you encounter cultural and historical contexts that are so alien they are almost undecipherable. As a comparison, think how difficult some phrases from Shakespeare are to understand. [2]

Pictures speak louder than words.

You might imagine that pictorial references, even in antiquated texts have more to offer than translations? But that also can be hugely problematic.

Here are two early martial arts examples that come to mind:

The Heiho Okugisho.

The earliest origin of parts of this martial arts book might go back as far as 1546, but really, who knows? Studies on this suggest it’s a chop-together of mostly Chinese sources that found their way to Japan and became really popular among martial arts enthusiasts in the Edo Period. It included, descriptions and drawings of techniques of spear and halberd, as well as empty-handed techniques and was eagerly devoured by aficionados and dilettantes alike and, according to one commentator, was passed around like porn mags or chicken soup recipes, with a hopeful belief that it was the real McCoy. But even with its enticing line drawings of men in antiquated Chinese dress, just about everything in it is bogus. Not to put too fine a point on it, it’s like a modern-day Photoshop fake. And still people studied it trying to tease out the ‘secrets’ hidden within and looking for the missing link of a Chinese connection to Japanese martial arts. [3]

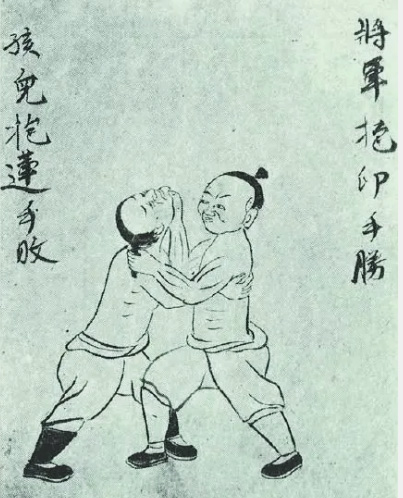

The ‘Bible of Karate – the Bubishi’.

This particular publication has a strikingly similar backstory to the Heiho Okugisho. The structure follows a comparable pattern and with the same maddening obscurities. Here is a book that was ‘kept hidden’ until around 1934 when parts of it were published in Japan. It emerged from Okinawa and so people inevitably connected it to Okinawan karate. It’s a book comprised of Chinese self-defence moves (line drawings and brief descriptions), various sections connected to herbalism and a questionable set of visual diagrams relating to ‘vital point’ striking. Much of it is written in flowery ancient Chinese characters that only the initiated have a hope of understanding.

When it was released as an English translation in 1995, I was eager to get my hands on it. Yes, it was intriguing and I studied it closely, trying to extract some kind of meaning from it. The drawings I could relate to, but any techniques I could find in them were quite basic; but really, what did I expect to find in line drawings with no meaningful accompanying text? Essentially, as a ‘how to do it manual’ it was (for me at least) a failure.

Over the last twenty-seven years more critical and well-informed eyes have examined the Bubishi and in some areas it is just not stacking up. Take for example its claim that it related to White Crane Chinese Gung Fu, and thus suggesting a clear link with Okinawan karate to a Chinese root. Apparently, according to experts in the field, White Crane has so much more to it than that, AND the ‘vital point’ diagrams look more and more like pure fantasy. [4] [5]

Here’s another one; not a book but a document:

“Itosu said…” well, did he really? And if so, what did he actually mean?

Some karate enthusiasts have eagerly brought their gaze towards an obscure, very short letter written by Okinawan karate master Itosu Anko (1832 – 1915) [6]. The letter was written to an Okinawan school board in 1902 and its intention was to explain in ten bullet points the virtues of karate training in the education system and a few basic guidelines as to how to approach training – to keep you on the right track. The letter has value by virtue of the fact it survived. In Okinawa so little was written and most of what was ended up in ashes as in 1945 the American forces had to pretty much raze large sections of the Okinawan islands to root out the resistant forces. But, as a cultural artefact Itosu’s letter is a hell of a rarity and really that is where its value comes from.

Some enthusiasts have rightly acknowledged the translation issue but have found themselves chasing after the wrong rabbit and have suggested that it is better to have a non-martial artist, non-specialist do the translation. Actually, it is that very problem that ruined Otsuka Sensei’s book for western audiences, because the English translation done by a non-martial art specialist misses out the nuances and implications of Otsuka Sensei’s carefully chosen characters.

With Itosu’s letter it is incredibly difficult to tease out anything beyond platitudes and generalisations, it’s not ‘The Da Vinci Code’ or the ‘Mayan Prophesies’, it’s a letter with a clearly defined audience in mind (the school board) and it pretty much does the job. For some people it has become a kind of manifesto, but if that is the case it is thin gruel. Yes, it is interesting, particularly as a snapshot in time and place, we can learn a lot from it as a cultural icon and there is much to gain from this window into a world long gone.

There are too many books and publications to go into in this post but I would like to put in some recommendations that particularly chimed with me and that I am prone to go back to time and time again.

- ‘The Unfettered Mind’ Takuan Soho. I have always loved this book, written some time in the 1630’s by monk/scholar Takuan Soho as a series of essays directed as guidance to the famous Yagyu clan of swords masters, teachers to the Shogun. The suggestion has always been that it was a Zen text but contemporary expert William Bodiford puts a good case that it is really a Neo-Confucian work (to me it fits far better than the contemplative approach of the Zen school of thinking).

- ‘The Tengu-Geijutsu-ron’ of Chozan Shissai (translation by Reinhard Kammer, published as ‘Zen and Confucius in the Art of Swordsmanship’). Written around 1728. Shissai expresses his ideas in a novel format and has harsh words for the swordsmen of his generation. The philosophical content and mindset come to life once you realise what he means by ‘Heart’, ‘Mind’ and ‘Life Force’ as it relates to Japanese martial culture. But there are some clever models and ideas scattered throughout the text.

- ‘The Sword and the Mind’ ‘Heiho Kaden Sho’, translation by Hiroaki Sato. The core essays date from the mid 1600’s and comprise practical guidance by the above mentioned Yagyu family. A great history section, but there is considerable content on the Mind and strategic outlook for the professional swordsman.

It won’t have escaped your attention that the above examples are all from swordsmanship, but it is my feeling that Japanese Budo/Bujutsu is well represented through the refinement of the art of the sword; particularly as it relates to the high level of psychospiritual culture that developed over many centuries and probably reached its zenith in the 17th century. The relevance of this is still present in our approach to training in modern martial arts, particularly Wado; weapon or no weapon, we carry a technical legacy that should still be with us, and we should always be trying to identify and reach towards those rarefied goals.

Conclusion.

Ultimately, reading any reliable material in and around your pet subject has to be a good thing. Understanding context, in particular, is crucial to getting under the skin and really understanding what you are doing. Many systems have depth and history and have gone through refinement and transformative processes to get where they are today. Generally speaking, reading is one of the most sure-fire ways of journeying into the cultural lineage of your system.

My view is that reading gives you glimpses of a mindset that is so very different from our own, whether it is the Itosu Letter or master Otsuka’s terse poetic axioms [7] it is clear that the time, the place and the culture inevitably wired-in ways of thinking and looking at the world that have entirely different priorities to the ones we have today. Yes, there are universal principles like justice and a desire for peace, but the societies were structured on pre-industrial almost feudal models (or were in the process of struggling to break free of those models) so it would be a mistake to simply project our views on to their writings.

In part two I intend to take a brief look at more modern examples (that may or may not be written with martial artists in mind) and look at how the west chooses to utilise eastern examples.

Tim Shaw

[1] Early text were hand copied, often generation after generation, remember, printing presses only worked well with European alphabets. Errors occurred, and then were magnified (Chinese Whispers).

[2] I have a particular fascination with the I-Ching, (said to be over 5000 years old). On my bookshelves I have five versions which I tend to compare against each other, the differences are quite startling.

[3] Reference; Ellis Amdur, ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’.

[4] See, https://whitecranegongfu.wordpress.com/2014/12/02/the-bubishi-myth/

[5] Consider the story of how Doshin So the founder of Shorinji Kempo was inspired to create his system after observing a mural painted on the wall of the Shaolin Temple, when he visited in the 1920’s and 30’s, showing Chinese and Indian monks training together. Although Shorinji Kempo history states that it was actually the spirit of training together that inspired Doshin So, not necessarily the technique. But it goes to show how pictorial imagery can inspire ideas.

[6] Itosu Anko is a very important figure in the more recent story of Okinawan karate and features at the point just before karate jumped from the islands to mainland Japan in the form of Itosu’s student Funakoshi Gichin, who was incidentally the first karate teacher of Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado Ryu. So, in some ways Itosu can be seen as the ‘grandfather’ of the Okinawan karate element contained within Wado.

[7] Master Otsuka composed short poems to express his ideas of how martial arts should function in the world. An example, “On the martial path simple brutality is not a consideration, seek rather an intense pursuit of the way that describes peace”. Source, article by Dave Lowry, ‘A Ryu by any other name’. Black Belt magazine, May 1986.

Bubishi Image credit: ‘Sepai no Kenkyu’ Mabuni Kenwa.

How detailed is your Wado map?

How confident are you about what you know of your system, the discipline you have chosen to study? Are you comfortable with the information you currently have to hand? Do you think you understand the roadmap of that developing knowledge, and is its trajectory obvious and predictable?

Okay, so, I accept that any Wado practitioner reading this might well be at very different points in their journey; some may be just beginning their study, others might be senior practitioners with many years behind them, but the ideas I am going to put forward I am fairly sure would benefit all – or at least stop and make you think. That’s the plan anyway.

Maps.

I am going to start with the broader idea, something I heard a little while ago. There is a theory that we all keep a complete map of the world within our own heads – a personal hardwired version like Google Satellite, Street View and Maps. When I first heard this, I was sceptical.

While I am fully aware that the human brain is perhaps the most complex thing on the planet but really this seemed a bit too far-fetched. But, it is true. That mess of grey matter that sits between our ears that has no awareness of itself outside of its own input devices – our senses, can really do all that, and more!

This amazing mapping, navigation device does not just include places, it also acts as our own personal encyclopaedia, with just about everything there is to be referenced. I use the word ‘referenced’ in a very deliberate way because the reality is that ‘references’ are about all we get.

To explain; while we have this map/encyclopaedia in our head most of this information is patchy and, in many cases, extremely low-resolution. The truth is, we have low-resolution representations of the majority of things we think we know.

Examples:

- Ask yourself about a random country in the world; say, Vietnam? Can you point to it on a map? Probably, but what else can your personalised encyclopaedia tell you? History, culture, language, currency? Unless you know the country very well through direct experience your knowledge will be sketchy, very low-resolution.

- Another couple of words; ‘Steam Train’. To communicate your understanding of this mode of transport, you might draw me a picture of a steam train, complete with funnel and wheels and a cab, all very ‘Thomas the Tank Engine’ – but unless you are an insanely enthusiastic trainspotter with qualifications in engineering and skills in mechanical draughtsmanship, I am not going to be convinced that you really understand a steam train, it will be extremely low-resolution.

Okay, so there are things we might be VERY knowledgeable about (or THINK we are), but the reality of our ‘wired-in’ intelligence and retrieval system (brain) is that it is in a state of constant update, or at least it should be. The truth is that (hopefully) more depth of information is being added and redundant (false) files are being deleted or replaced and new entries or categories are being added.

In some areas, people actually choose not to update their maps and files, this is often found when people become entrenched in areas like politics. Clearly, individuals can be so profoundly tribal in their political beliefs that even in the face of irrefutable evidence they will argue that black is white. But that’s their problem.

How about Wado (or any martial arts system)?

All of the above can be applied to our understanding of Wado karate.

I think it’s a case of being totally honest with yourself; particularly those who have been on this pathway a long time. Come on, do you really believe the same things that you did twenty years ago? How have your files been updated?

An example:

I came to the conclusion a long time back that just about everyone I knew in the martial arts continued their training for completely different reasons than those they started with. It might have been that they initially wanted to build confidence; they were fearful about their ability to protect themselves; but then, over time, their maps changed, their references became more sophisticated, more nuanced and they found something new, something of substance. I can’t get into describing what that is in this post, I don’t have the space; (in some ways I explored this idea in my blog post ‘Martial Arts training and the value of finding your Tribe.’).

Your Wado map.

For every student of Wado karate your initial ‘map’ is usually found in the pages of your syllabus book. This map expands as you move through the grades. Although, I must say, the reality is, it’s not an easily accessible map because it is mostly written in a different language.

But it would be naïve to assume that when we have completed the book we have mastered the system, it doesn’t work like that. The syllabus is a very low-resolution representation of the system; really, it’s a loose framework designed for convenience. In addition, ‘knowing’ the book, with its Kihon, Kata and Kumite doesn’t guarantee you can actually do it; and doing it doesn’t mean you can apply it. Imagine a musician who can read sheet music but can’t play an instrument, or who can play the music accurately but cannot improvise!

The downside of the syllabus book.

In Wado I don’t think reliance on the syllabus book is particularly helpful; it’s a pretty poor map. For me it’s too linear. For systems other than Wado it might easily describe the structure in a straightforward and accurate way, but within Wado karate it only takes you so far in understanding the true nature of this very unique Japanese Budo system. In fact, I would go so far as to say that if the book is the only model/access route, it will ultimately lead you down a dead end. [1]

A different map.

In some of my more recent teaching seminars I have presented a completely different map; a pictorial diagram that I think enables Wado students to navigate a more useful and meaningful way of understanding Wado – but a blog post like this is not the place to share this idea; besides, it is still a work in progress, as it should be. [2]

Expanding the map or increasing the resolution?

I think it is too easy to misread what I mean by developing or expanding the map. I don’t think that the Wado map should be seen as a kind of growing, territorial colonialisation, similar to a video game like ‘The Settlers’ or ‘Minecraft’ where from a tiny localised centre you keep occupying new territory and building new structures; that would be like adding extra pages on the end of the syllabus book.

To give a concrete example: Otsuka Sensei was quite content with the idea of nine core solo kata, anything beyond the apex kata of Chinto was classified as ‘extra’. [3]

Paired kata are perhaps another story. If you take them on face value, they are legion! But to focus on their bewildering number is perhaps missing the point.

I speculate that with the paired kata there is a hidden map lurking beneath the seemingly complicated map which features, for example; the ten Kihon Gumite, the thirty-six Kumite Gata, twenty-four Ura no Kumite and all the rest. The clue is when you acknowledge the reality that none of these paired kata contradict the core principles, and it is these core principles that are the real map, the one skulking underneath, and, in content, the ‘Principle Map’ is not such a huge numerical challenge.

The most valuable approach is not necessarily to expand the territory, but to increase the resolution. The territory might well push beyond its boundaries but only in a natural, unforced way, an organic by-product of more defined and focussed examination. The real payback is in the more granular exploration of areas you already think you know.

‘Low-resolution’ has its uses.

Low-resolution thinking is natural to us, it’s the very basic of what we needed to survive and has been with us for tens of thousands of years. But what might have been paramount for hunter-gatherers has now slipped down our list of priorities – I mean who needs to clutter up their thinking about what they might have had for breakfast when they are being chased by a sabre-tooth cat? A boost of adrenalin and the most basic info about an escape route should be enough!

What does ‘increasing the resolution’ mean for your Wado?

Let me start with what it does NOT mean:

- It does not mean knowing more and more about less and less.

- It does not mean you become a slave to detail, which, if taken to its extreme can result in you looking like an obsessive dilettante, all ‘head knowledge’ and no practical/physical skills. [4]

- It does not limit your thinking by allowing you to assume you have it all pinned down. Actually, the reverse should happen; your mind continues to expand.

What it DOES mean is:

- The more granular your understanding the more you appreciate the relationships between the various parts of your Wado map, the underpinning logic.

- This increased resolution enhances your creativity.

- If approached with humility, you begin to realise how little you know, or how things you thought you knew might have been wrong.

How to adopt a ‘granular’ approach to something you thought you knew.

As an example; never, never, never underestimate or dismiss Kihon, I say that because if you take something like the action of Junzuki, this single technique taught at the beginning of your training reveals so much more depth. Why do you think that no matter how many years you have been training you never leave Junzuki behind, you never transcend it? It’s always a work in progress.

But I guess you expected me to say that.

Another example: Take something like the role of ‘Uke’ in paired kata… it took me far too long to realise that Uke is not a mere stooge for the person performing the prescribed technique. Uke has more say in the conversational process and this ‘conversation’ continues all the way to the end of the kata.

The double-edged sword.

I left this part till the end, but it is incredibly important. Essentially, having knowledge in your head is no good on its own. For it to be given any form of concrete real-world potency, the other form of ‘knowledge’ must accompany it; that is the absorption of the technique into your body, to borrow someone else’s rather excellent description; it must be so deeply engrained that it stains your very bones!

Tim Shaw

[1] Yes, we have a syllabus book in Shikukai, and yes it has its uses as an outline, a catalogue of techniques and requirements for grading, but that’s it.

[2] I have been toying with the idea of sharing this type of material through a subscription service like Substack, but I haven’t made my mind up yet.

[3] Notice how the kata Suparinpei dropped off Otsuka Sensei’s map very early on. Also consider Otsuka’s early development of Wado and look at the list of techniques produced for the official registration in the 1930’s; it’s a kind of map, but what was its objective? Who was the map really for?

[4] ‘Dilettante’, I like this much underused word. Definition; ‘A dilettante was a mere lover of art as opposed to one who did it professionally.’

Photo credit: The Settlers screen image courtesy of: https://www.sockscap64.com/games/game/the-settlers-2/

Book Review – ‘The Way of Judo, a Portrait of Jigoro Kano and his Students’ John Stevens.

A biography of the founder of Judo and what his life tells us about Japanese martial arts and modernisation.

You might ask what a book about the originator of Japanese Judo is doing appearing on a blog about Wado karate? To explain this, I don’t think it’s too bold a statement to say that Kano Jigoro was instrumental in creating the martial arts eco-culture that the founder of Wado Ryu, Otsuka Hironori, was brought up in. Kano was a moderniser and an iconoclast and so was Otsuka, although Kano was senior to Otsuka by nearly thirty years. Otsuka may have known of Kano but I doubt there was any close connection (Kano died in 1938, the same year that Otsuka founded Wado Ryu as a separate entity – Otsuka lived on until 1982). I will put forward a few observations and speculations about master Otsuka later.

The book itself.

There were so many things about John Stevens biography of Kano that surprised me. I already knew that he was the early model for Japanese modernisation and instrumental in the survival of the cultural legacy of the Old School Japanese Jujutsu, albeit packaged into a new form (how successful he was is too big a subject to go into here), but there was so much more to the man.

Here are some intriguing facts about Kano (to me anyway):

- Kano came from the higher tiers of society, so, financially and socially he already had a leg-up the ladder. Otsuka and his good friend Konishi (1) also came from more than secure backgrounds. These advantages allowed scope for freedom and exploration, as much as Japanese society allowed at the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century. Add to that a fanatical desire to dig really deeply in their chosen field and something truly special emerges with all three men.

- Kano was a traditionalist in martial arts (jujutsu) terms, but also a moderniser who was able to get a significant number of the old school hardened jujutsu masters on-board to synthesise their teachings into modern judo… how was he able to do that?

- Kano suffered considerable set-backs as he struggled to formulate, promote and develop Kodokan Judo, however, his tenacity seemed almost super-human. Clearly the man had charisma and amazing persuasive powers, and, in the early days, led from the front – he could walk the walk!

- Amazingly, he looked towards western culture to find models that would work for the Japanese people. He admired the philosophical ideas behind western physical education but hated the modern concept of ‘sport’, which to him trivialised and subverted the purer objectives of the physical culture of the martial arts (ironic when you think of his legacy today). Interestingly, it was open contests that boosted the status of Kodokan judo in the early days (2). A real shock to me was that although Kano was actively involved in the Olympic movement (particularly the failed bid for the 1940 Olympic games in Tokyo) he was actually reluctant to suggest that judo should be included, for fear that the appetite for medals and glory would be the opposite of how he saw the reality of judo.

- Stevens says that in technical judo Kano was not a fan of groundwork, but understood it as a necessity if he was to make his point. For Kano it was 70% stand-up and 30% groundwork, Stevens quotes a saying, “To learn throwing techniques well, it takes three years; to learn effective groundwork, it takes three months”. (Stevens does not give the origin of the quote).

- It seems clear that even within his own lifetime Kano’s judo was being subverted into something he was desperate to avoid. Everything that he frowned upon in modern sporting culture was acting as a magnet to the coaches and youngsters they taught. Kano was clear in his mind what the model for judo should be and he explained it in language of high ideals, but perhaps these ideals were too abstract and contradicted where the world was actually going? Kano was swimming against the tide.

- In his working life Kano was a model professional educator. His whole career was in education, he genuinely cared about people. As a scholar and a life-long learner he was a wonderful example of an insatiable and a genuine polymath. E.g. it is known that he wrote all his early training notes in English to keep them secret from his fellow trainees. What also surprised me was that Kano is considered the father of music education in Japanese schools, being instrumental in making music compulsory for all middle and high school students.

- He was without a doubt a rebellious figure, in that he kicked back against Japanese conservative views on education and he resisted the militarisation and appropriation of Japanese martial arts to fuel war and expansionism. This would have surely ruffled a few feathers at the time. Some of his political contemporaries were actually assassinated for holding opinions similar to his.

- His successes came at a price, in that he acted as a lodestone for various martial arts crazies, obsessives and prodigies (positive and negative). Too many to choose from, but to name two; Saigo Shiro and Mifune Kyuzo (3).

- Kano died at the age of 77 on board ship on his way back to Japan. It’s just my opinion but I suspect he was just burnt out.

Otsuka Hironori and Judo.

I think it is important to explain that the terms ‘Jujutsu’ and ‘Judo’ were loose descriptions that had been interchangeable for a long time, even before Kano’s ‘ownership’ of the term as a handle for Kodokan Judo.

Regarding Otsuka Sensei; even before he reached his teens Kano’s Kodokan was becoming a major force in Tokyo and beyond, how could he fail to be influenced by it?

In 1906 Kano had opened a huge 207 mat Dojo and the standard Judo Keikogi (uniform) had been established by this time. Coincidentally, one of the earliest pictures of Otskuka Ko (as he was then named) is of him in a group photo of ‘Judo’ students at middle school wearing this new keokogi, this was 1909 and he was in his late teens. While at school he was heavily involved in judo as it was evolving and working its way into the education system. He is also in the school records of 1909 as taking part in the school’s winter training and earmarked as one of the most promising judo students. (Apparently had some particularly strong throwing techniques).

In 1908 the government decreed that all middle school students should be doing either judo or kendo. We know from Otsuka family anecdotes that Otsuka Ko’s mother discouraged her son from kendo, and he had some background training from his mother’s uncle in old school jujutsu and on top of that Otsuka was to come under the influence and tutelage of Nakayama Tatsusaburo, the middle school’s hired coach, who clearly taught him judo and opened the door to him learning Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu which is largely recognised as being one of the base-arts of Wado Ryu.

In his book, ‘Karate Wadoryu – from Japan to the West’ Ben Pollock mentions that “There is the possibility Otsuka was practicing judo at the Kodokan at some point in the period prior to him starting his study of karate-jutsu”. Clearly this possibility is not beyond the bounds of credibility, it is known that Otsuka was well connected with some of the leading lights of the Kodokan, including Mifune.

Is there any surprise that Otsuka’s concocted curriculum he submitted to the Butokukai in 1939 to register the name and the style ‘Wado Ryu’ was padded out with techniques from the established judo canon? Look at it from this angle; a huge percentage of those who went through the Japanese middle school would have a pretty good idea of what those throws were, they weren’t unique to Wado, they were common techniques. In the same way if you asked an English schoolboy the basic mechanics of manoeuvres in football, he’d be able to tell you; it is part of the system and the way physical education is taught. This is not to take anything away from Otsuka, as it is known that his grappling skill was at a very high level.

But what intrigues me the most was not the technical base of the influence of judo and Kano on Wado, but the philosophical and organisational approach Otsuka later took. Did Kano’s example act as a beacon of influence for Otsuka?

Japan was breaking the traditionalist mould and Kano’s example may have showed Otsuka that this can be done, and that the climate was right.

As an example; Kano is said to have originated the basic idea of the belt system (although the many coloured belts is rumoured to have originated as a later development in Europe). The way we work today, our hierarchies, ladders of promotion, syllabus developments all relate to how things are done in the education system – some people say it is more closely related to military systems, but that argument becomes very ‘chicken and egg’. Remember, Kano was the educationalist with a vision for the whole of Japan and the wider world (hence his involvement with the Olympic movement and the ideas of Baron de Coubertin).

Wado, like other systems rejected the long-established certification system of the Koryu (Old School) Japanese martial arts and adopted another, modernised, system; Kyu/Dan ranking. It was workable, particularly as Dojo branches then became sub-branches, then regional branches, followed by national branches etc. At some stage, somebody must have thought this was the way to go. It has a certain convenience to it. Committees sprang up like mushrooms and seniors became ‘officials’ and then, I suppose ‘suits’ (4). The move towards factoryfication became inevitable, and in many of the larger Wado organisations continues today.

Personally, I don’t look at the Kano story as just something that belonged in its historical time, there are lessons and parallels to be drawn that are just as relevant today. John Stevens did an amazing job with the book and tried to strip away any hint of propaganda and in doing so presented Kano as a formidable figure, but with human flaws. It would be a huge loss for the example set by Kano to be buried in the history books.

Tim Shaw

1 Konishi Yasuhiro, 1893 – 1983 founder of Shindo Jinen Ryu karate, an early pioneer along with Otsuka. As with Otsuka Konishi started out as a traditional jujutsu practitioner, they had a lot in common.

2 The ‘contests were billed as ‘exchanges of techniques’ or ‘exhibition bouts’ and unashamedly pitched school against school; the aim was for Kodokan judo to come out on top, and many times they did. ‘Exchange’ training also happened in the early days of Wado, as Suzuki Tatsuo recounts in his autobiography. So, this was definitely part of the culture.

3. Saigo Shiro 1866 – 1922, was a prodigy of Kano’s judo and elevated the status of the art in early contests, but he was hot-headed and his bad behaviour forced Kano to expel him from the Kodokan.

Mifune Kyuzo 1883 – 1965, another prodigious talent, sometimes referred to as ‘the god of judo’ Mifune was only 5 foot 2 inches and weighed only 100 lb but he was unstoppable and took over the Kodokan after Kano’s death.

4. A phrase that came to suggest; those who no longer actively trained but their authority came from association with Otsuka Sensei way back when.

Cover photo source Amazon Link.

Martial Arts training and the value of finding your Tribe.

I think everybody has heard the saying, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts” [1] attributed to Aristotle. It is a useful phrase when applied to the accumulated value we get from our martial arts training, and particularly when we look at the way our various organisations endeavour to support us in our ambitions and travels along the Martial Way.

I want to look at this contribution from the individual martial artist’s memberships and loyalties to their organisations, as well as to the allegiances and bonds they feel towards their fellow trainees who accompany them on their journey – this I will call the ‘Tribe’.

Your Tribe (sources and references).

It is not an original idea, it’s certainly not my idea. For this I am indebted to the book, ‘The Element – How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything’ by the late Sir Ken Robinson (with Lou Aronica) [2].

There are so many interesting and inspirational parts to this book, but I will just focus on just this one, as I feel it is maybe something we should make a conscious effort to appreciate and understand, and, if you are in the upper hierarchy of your martial arts organisation, it is worth taking this seriously, as it applies not just to you, but also to every one of your students no matter what their age or level.

In this book Ken Robinson makes a huge thing about the importance of ‘Tribes’ for enabling human growth through finding what he calls ‘your Element’, as in, ‘being in your Element’ and finding the true passion in your life. This could be through anything; through sports, through the arts or the sciences, but, although it is possible, you might struggle to thrive and develop in total isolation, the energy you get from being part of a Tribe of people all working towards the same thing is truly empowering.

Here are some of a huge list of benefits.

You could start with what it means to share your passions and connect with others; the common ground and the bonding has a power all of its own.

Antagonists – the grit in the oyster.

Within the Tribe you meet people who see the world as you do, they don’t have to totally agree with you, but you are in the same zone. In fact, disagreeing with you can create a useful friction and even challenge your established views, which in itself promotes growth.

Collaborators and Competitors.

Robinson says that in the Tribe you are liable to meet collaborators and competitors; a competitor isn’t an enemy, it is someone you are vying with to race towards the same goal, and as such that type of tension can energise you, and the heat of battle (competition) inspires further growth, it’s a win-win.

Also, if your competitor has a different vision, this vision can help to validate your personal goals and either justify or revise your overall views.

Inspirational models.

Tribe members can act as motivators, their acts and sacrifices can inspire you, and remember, the positive relationships don’t have to be vertical, as in looking up to your seniors; but also horizontal, seeking inspiration from your peers. Of course, it is entirely possible that your tribal inspirational models might include people who are no longer around, I include past martial arts masters and not necessarily the ones you have been lucky enough to meet.

Speaking the same language.

Being in the same tribe means that you have to engage in a common vocabulary, but you also have to develop that language to explore ideas.

Your tribe members may perhaps force you to extend your vocabulary, to deal with more complex or nuanced aspects of what you are doing – very obvious in the martial arts, as some of these concepts might be outside of your own cultural models. I can think of many times when talking with fellow martial artists that my descriptions seem to fail me, and then someone will come up with a metaphor I’d never thought of, an inspired comparison or natty aphorism which just sums it up so neatly, and, of course, I will shamelessly steal it. You couldn’t do that on your own, you have to have the sounding boards, the heated debates, or even the physical examples (because, not everything happens at the verbal level, in fact we thrive on the physicality of what we do!).

Validation.

This is something that the martial arts have the potential to do particularly well. I say ‘potential to’ because it seems to almost be taken for granted. I believe that the frameworks used, particularly in karate organisations, are a good example of how to support, validate and acknowledge the individual student’s dedication to their training.

Done properly, this happens in two ways; the first being the official recognition of achievement, an example might be, gradings, which act as a rubber stamp and are generally accepted across the wider martial arts community. In individual or group achievements we are respectful and genuine in applauding our fellow students, which adds real value and meaning to all the blood, sweat and tears and makes it all feel worthwhile.

The second way is more subtle though not lesser in value, and that is related to the softer skills, the buzz of being shoulder to shoulder, the unspoken nod from your instructor or your fellow trainees, the respectful bow, all of these send signals that validate and add value to your membership of the Tribe.

Being in the right Tribe.

Of course, it is entirely possible that you might find you are in the wrong Tribe. There might be something about it that is just doesn’t work for you. If that’s the case then a great deal of soul-searching may have to take place. I suspect that in the past this same ‘soul-searching’ for some people can take far too long; as the saying goes, ‘What a tragedy it is that you’ve spent so long getting to the top of your ladder only to find that it’s propped against the wrong wall’.

You will know that you are in the right Tribe when it ticks all the boxes; not just the above points, but also you will notice that your creativity is boosted, your life feels energised and given meaning.

The Tribe is the fertile soil of personal growth. Robinson says that “Finding your Tribe can have transformative effects on your sense of identity and purpose. This is because of three powerful tribal dynamics:

- Validation.

- Inspiration.

- ‘The alchemy of synergy’.”

I write this at a time when tribes are just beginning to re-emerge after the pandemic. There has never been a more apposite time to appreciate the value of your tribe – just look for the smiles the first time the whole tribe truly gets together.

Tim Shaw

[1] For anyone interested, it is a key aspect of those who support the Gestalt theory in psychology and the concept of ‘Synergy’ (definition: ‘the interaction or cooperation of two or more organizations, substances, or other agents to produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate effects’. Oxford Languages definition).

[2] ‘The Element – How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything’ by the late Sir Ken Robinson (with Lou Aronica) https://www.amazon.co.uk/Element-Finding-Passion-Changes-Everything-ebook/dp/B002XHNMVM

You’d better hope you never have to use it – Part 2.

“Smash the elbow”, “tear the throat out”, “snap the arm like a twig”, “gouge the eyes with your thumbs”. I have heard these things said by martial artists during classes. But I find myself asking, how do you know? and have you ever done that? Have you ever used your thumbs to gouge out somebody’s eyeballs? And on top of that, how do you know you won’t freeze like a rabbit in the headlights? Or, how do you know if you have enough resilience (or lived experience) to be able to suffer a terrible beating before you get a chance to put in that one decisive game-changing shot?

Empirical evidence versus anecdotes.

Effectiveness, can you prove it? Can it be quantified in a scientific way? Is the data available?

Every martial artist probably has a dozen stories as to why their martial arts method is effective as a fighting system and none of these incidents ever happen inside the Dojo – how could they, it’s supposed to be a safe training environment?

I have my own ‘go-to’ anecdotes, but equally I have another set of anecdotes where martial arts practitioners have come unstuck – but nobody talks about those, least of all the people who it has happened to (understandably). [1].

Anecdotes may be fun to recount but all they do is muddy the water, they are too random to qualify as evidence. And, if you look at some of these stories in the cold light of day you often have to wonder about (a) their veracity, (b) which way the odds were stacked, (c) whether elements of luck or chance were involved; but one thing is clear, they cannot really be used as definitive proof that your system works, after all, the system is the system and You are not the system.

The anecdotes may suggest that in certain circumstances your chances of coming out on top in a violent attack might be slightly higher – but they could also suggest that you might come out worse (probably because of over-confidence, or an unrealistic evaluation of your own ability).

The problem with fantasy.

Now compare that to movie fantasies of physical confrontations. I cite two examples that come to mind.

The first being Tom Cruise as Jack Reacher, where Reacher takes a bunch of guys on after they offer him out from a bar ( link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hu1MtT_S3bc

The thing is, deep down, we all want it to be like that.

And then Robert Downey Jnr as Sherlock Holmes in a bare knuckles contest (link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-z5139CW1I

This last one is about as extreme an example as is needed to make my point that fantasy is fantasy. (To paraphrase Mike Tyson, ‘Everybody has a plan until they get a punch in the mouth’.)

The Sherlock Holmes example is akin to treating violence like a chess game – if I plan and think several moves ahead then my plan will bring about the downfall of my opponent…. wrong. When it gets to the ‘trading punches’ stage you have already entered the world of chaos, thus ramping up the unpredictability exponentially.

It is potentially fatal to confuse Complex with Complicated [2] and the zone of chaos is indeed Complex. This is why those who are supremely skilful at navigating the Complex world have to do it without thought, artifice or calculation, they are like expert nautical mariners in a tossing sea, who work on instinct, they have an overarching understanding of Principle, their skills are not a bunch of cobbled together tricks that they have memorised hoping for that moment to happen.

I know that there are critics of the Principle angle in martial arts (particularly Wado), usually they fail to understand it and ask, what is this ‘Principle’ thing anyway? I am tempted to reply with something like the Louis Armstrong quote about the definition of jazz, “Man, if you have to ask what jazz is – you’ll never know”. (See my blog post on ‘Fast Burn, Slow Burn Martial Arts’ for a clue as to how it works). These same people remind me of the ‘Fox with no tail’ a moral story from Aesop].

When people talk about ‘functionality’, ‘functional combative skills’, this has to be about effectiveness, surely? But You can’t talk about that without some form of measure, if there is no measure then it’s all opinion and as such, we can take it or leave it. The person who makes the statement can only hope that we trust their opinion as an ‘expert’, but again, an expert based on what experience; their ability (as proven) to ‘snap someone’s arm like a twig, or gouge their eyes out’? I realise that there are people out in the martial arts world whose whole authority rests on this issue and it’s not my place to call them out, particularly as I also have no experience of ‘snapping arms’ to support any claims I make, but just apply a little logic to it.

Of course, I reckon that if I take my opponent’s elbow over my shoulder and exert a forceful two-handed yank downwards I might be able to ‘snap his elbow like a twig’, but I doubt he’s going to let that happen without a hell of a struggle (unless I am Sherlock Holmes of course). Meanwhile, he has barrelled into me, knocked me on my back and is sat on my chest raining punches into my face, and then his mates join in to kick me in the head for good measure – elementary my dear Watson.

Looking for evidence in history.

I feel I have to address this one. Anyone who looks for evidence in history is on to a sticky wicket. History is notoriously unreliable. We know this because current historical revisionist methods are revealing that many things we thought were true may not be so. For example; everyone knows that it is the victors who write the history.

If we take our history inside Japan and Okinawa and we listen to serious, open-minded researchers, we find that some of the things we took for granted may well not be true.

To give a few examples:

- Zen Buddhism does not have the monopoly in Japanese martial arts, certainly karate is not ‘Moving Zen’.

- The 19th century Samurai were not the apex of Japanese martial valour and skill. Set that two or three hundred years earlier and you might be about right.

- Okinawan martial arts were not the result of a suppression imposed by Japanese Samurai; it was not that simple. Okinawan people were generally peaceful and society was well-structured, it certainly was not the Dodge City that some people like to suggest, it seems that the martial arts of Okinawa reflected this, an extreme martial arts crucible it certainly wasn’t, certainly if you compare it with what was happening in Japan between 1467 and 1615. I don’t point that out to discredit the Okinawan systems, it’s just an observation and there were exceptions, e.g. Motobu Choki, who certainly had his ‘Dodge City’ moments.

As time moves forward all we are left with is the mythologies, hardly something to judge the functional abilities of teachers who are long dead, so all we have available is guesswork, assumptions and opinions; not really scientific or objective. So, anyone who wants to hang their ideas on that particular hook would be wise to keep an open mind.

How would martial arts work in a defence situation? A proposition.

To answer this, I would speculate that there are several high-level outcomes that are possible, and none of them look anything like either the movie fantasy image, or the types of techniques that are, ‘a bunch of cobbled together tricks that have been memorised hoping for that moment to happen’ [3].

- The highest level has to be that nothing happens, because nothing needs to happen. The world calms down and order rules the day; chaos is banished.

- The next highest level is probably where the aggressor just seems to fall down on his own. Here are my two nearest assumptions on this (one anecdotal and the other historical – but after all, I have to pluck my examples from somewhere). The first is a story about Otsuka Sensei dealing with a man who tried to mug him for his wallet in a train station. Otsuka just dealt with the guy in the blink of an eye and when asked what he did, he replied, “I don’t know”. The other is the historical encounter between Kito-Ryu Jujutsu master Kato Ukei and a Sumo wrestler who twice decided to test the master’s Kato’s ability with surprise attacks, and both times seemed to just stumble and hit the dirt [4].

- Anything below those two levels would probably involve one single clean technique, nothing prolonged, maybe appearing as nothing more than a muscle spasm, nothing ‘John Wick’, certainly nothing spectacular – job done.

- Then you might plunge down the evolutionary scale and have two guys smashing each other in the face to see who gives up first.

Conclusions:

The original objectives of these two blog posts were to challenge the assumptions we seem have made about the nature of self-defence (in its broadest interpretation) and to put forward some different angles, explode a few myths and to present the idea that all that glitters is not gold.

I don’t have the answers, but then it seems, neither does anyone else. But we shouldn’t just throw our hands up in the air. Keep on with the focus on defending ourselves and refining our technique and by all means teach self-defence as a supporting disciple or on dedicated courses, it is a brilliant way for martial arts instructors to engage with the community in a positive and confidence building way; however, keep it realistic and not just fearful.

For those who claim that their approach has more ‘functionality’ I would humbly suggest that that you might want to look towards the key questions; objectively, how can you prove that? Maybe what you are asking for is a leap of faith? My view is that the data is not there and that it is just lazy logic. [5]

There are people who want to claim their authority from the ‘short game’, while I would suggest that there is another game in town; the ‘long game’. Targets really need to be aspirational and ambitious, not ducking towards the lowest common denominator, i.e. the ‘fear factor’ of the anxious urbanite. Your authority is not derived from your ability to ring the metropolitan angst bell; or to yank the chain of the frustrated metrosexual male who feels he is cut adrift and fretful about his role in contemporary society and lost in a maelstrom of surging confusion.

The bottom line is; get real and dare to think differently.

As a last word, these posts are not meant to be definitive, or to cover all aspects of self-protection. I could have included comments about how the law views self-defence, or how much mental attitude is a part of self-defence, or adrenalin, fight and flight etc, without even mentioning the number of young men in the UK who die through stab injuries. But maybe another day.

Tim Shaw

[1] One event happened fairly recently where I had bumped into a martial artist from another system, an acquaintance, in a nightclub. He’d had a drink or two and proceeded to bend my ear about how ‘the trouble with most martial artists is they have never been in a real fight, never trained for it, etc.’ And, as if the God of Irony was looking down upon him; within seconds of him waving me goodbye, he crossed paths with the wrong person and ended up as a victim, laid out and bleeding. I guess he didn’t get the chance to ‘snap the arm like a twig’.

Be careful what you wish for.

[2] See my blog post on Systems. https://wadoryu.org.uk/2020/01/29/is-your-martial-art-complicated-or-complex/

[3] These methods often assume that the opponent is going to present themselves like a bag of sand and allow you to engage in an ever-complex string of funky locks, take-downs, arm-bars etc. etc. Sherlock Holmes would definitely approve.

[4] Source: ‘Famous Budoka of Japan: Mujushin Kenjutsu and Kito-ryu’. Kono, Yoshinori, Aikido Journal 111 (1997). According to Ellis Amdur in his book ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’ this is pure Principle and Movement in practice (my paraphrase).

[5] Similar to the way people talk out about ‘life after death’, i.e. how do you know? Conveniently, nobody has ever come back to tell us. Ergo; you never have to validate your claims.

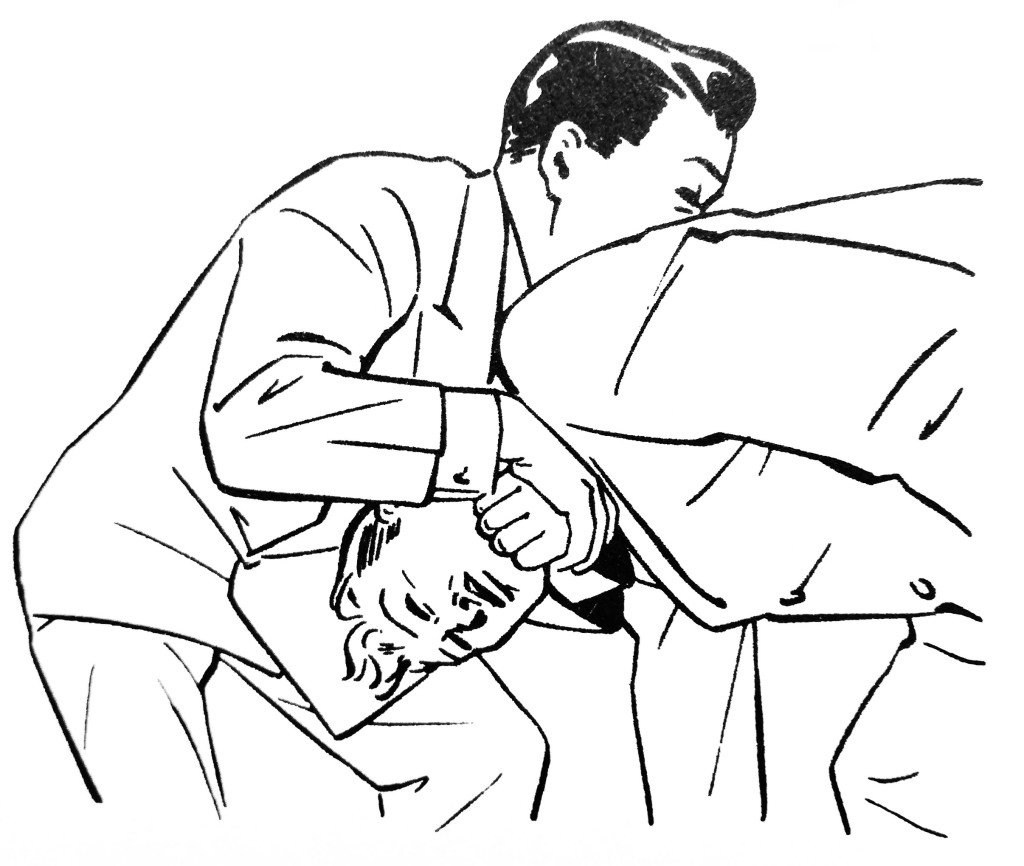

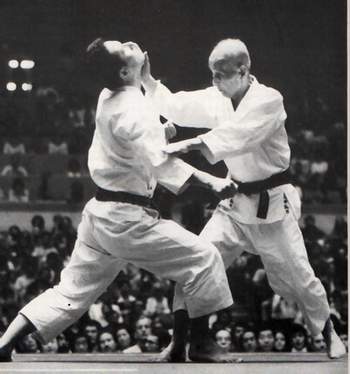

Image credit: Kiyose Nakae ‘Jiu Jitsu Complete’ 1958.

Martial Arts, fast burn or slow burn? – A theory.

This is something I have been thinking over for some considerable time. I believe that almost all martial arts training systems exist on a spectrum from ‘fast burn’ to ‘slow burn’.

Bear in mind that when boiled down to their absolute basic reasons for existence, all martial arts are about solving the same problem – protection/reaction against human physical aggression.

Fast Burn.

At its extreme end on the spectrum ‘fast burn’ comes out of the need for rapid effectiveness over a very short period of training time.

A good example might be the unarmed combat training at a military academy [1].

There are many advantages to the ‘fast burn’ approach. A slimmed down curriculum gives a more condensed focus on a few key techniques.

As an example of this; I once read an account of a Japanese Wado teacher who had been brought into a wartime military academy to teach karate to elite troops. Very early on he realised that it was impossible to train the troops like he’d been trained and was used to teaching, mainly because he had so little time with them before they were deployed to the battlefield or be dropped behind enemy lines. So, he trimmed his teaching down to just a handful of techniques and worked them really hard to become exceptionally good at those few things that may help them to survive a hand-to-hand encounter.

Another positive aspect of ‘fast burn’ relates to an individual’s physical peak. If you accept the idea that human physicality, (athleticism) in its rawest form rises steadily towards an apex, and then, just as steadily starts to decline, then, if the ‘fast burn’ training curriculum meshes with that rise and enhances the potential of the trainee, that has to be a good thing.

In ‘fast burn’ training, specialism can become a strength. This specialist skill-set might be in a particular zone, like ground fighting and grappling, or systems that specialise in kicking skills.

The down side.

However, over-specialisation can severely limit your ability to get yourself out of a tight spot, particularly where you have to be flexible in your options. Add to that the possibility that displaying your specialism may also reveal your weaknesses to a canny opponent.

It has to be said that a limited number of techniques whose training objectives are just based upon ‘harder’, ‘faster’, ‘stronger’ may suffer from the boredom factor, but, by definition, as ‘fast burn’ systems they may well top-out before boredom kicks in and just quit training altogether. They may well be the physical example of what the motor industry would call ‘built-in obsolescence’. [2]

Not that a martial art should be judged by its level of variety.

As a footnote; it is a known fact that in some traditional Japanese Budo systems students were charged by the number of techniques presented to them, so it was in the master’s interest to pile on a growing catalogue of techniques. I am not saying this was standard practice, but it certainly existed.

Slow Burn.

Turning my attention now to ‘slow burn’.

By definition ‘slow burn’ martial arts systems develop their efficiency over a very long time, or perhaps time as a measure is misleading? Maybe it would be better to describe the work needed to become a master of a ‘slow burn’ system as prolonged and arduous, perhaps beyond the bounds of most individuals.

For me ‘slow burn’ is defined by its complexity and sophistication and is associated with systems that have demanding levels of study, probably involving insane amounts of gruelling and boring repetitions that would test the ability (or willingness) of the average person to endure.

The positive side.

The up-side of this methodology is difficult to map as so few individuals ever get to the level of mastery and all we are left with are martial arts myths, but it would be foolish to dismiss it on these grounds alone. Most myths contain a kernel of truth and if a fraction of the myths told can be effectively proved or verified then really, there is no smoke without fire.

Looked at through the lens of modern sporting achievement, I think we can all appreciate that with the very best elite sportspeople uncanny abilities can be observed, and we know that despite the fact that many of them are blessed with unique genetic and physical disposition, an insane amount of work goes on to achieve these lofty heights (I am thinking of examples in tennis or golf, but really it applies to any top-level human endeavour – think of musicians!).

‘Slow burn’ martial arts systems may not comply with modern sports science used by elite athletes, but they were getting results any way, probably from a form of proto-sports science developed through generations of trial and error.

The ‘slow burn’ systems seem to be characterised by a reprogramming of the body in ways that require great subtlety, so subtle in fact that the practitioner struggles to comprehend the working of it even within their own bodies; it works by revelation and is holistic in nature. Mind and cognition are major components. The determination and grit that fuel the ‘fast burn’ systems are not enough to make ‘slow burn’ work, something more is needed; a reframing and reconfiguring of what we think we are doing.

Weaknesses.

The weaknesses of the ‘slow burn’ systems are pretty obvious.

Who has the time or patience to involve themselves in this level of prolonged study? It certainly doesn’t easily mesh with the demands of modern living; an awful lot of sacrifices would need to be made. It is no exaggeration to say that you would have to live your life as a kind of martial arts monk, casting aside comforts and ambitions outside of martial arts training. I often wonder how it was achieved in the historical past; I guess that beyond just living and surviving they had less distractions on their time than we do now. [3].

We know something of these systems because we can observe how, over time, the surviving examples had a tendency to morph into something altogether different; often taking on a new and reformed purpose, which of course improved their survival rate.

The examples I am thinking of have reinvented themselves as either health preserving exercise or semi-spiritual arbiters of love peace and harmony; all positive objectives in themselves and certainly not something we need less of in these current times.

I am going to duck that particular argument; it is not a rabbit hole I am keen to go down in this current discussion.

‘Slow burn’ dances with the devil when it too eagerly embraces its own mythologies; but in the absence of people who can really ‘do it’ what else have they got left? What always intrigues me is that the luminaries of the current crop of ‘slow burn’ masters are so reluctant to have their skills empirically tested. [4]

It is tempting, but it would be wrong to play these two extremes of the spectrum off against each other; I have deliberately focussed on the polar opposites, but it’s not ‘one or the other’, there are martial arts systems that are scattered along the continuum between these two extremes, and then there are others that have become lost in the weeds and suffer from a kind of identity crisis; aspiring to ‘slow burn’ mythologies while employing solely ‘fast burn’ methodologies. Can a man truly serve two masters? Or is the wisest thing to do to step back and ask some really searching questions? What is this really all about?

And Wado?

And, as this is a Wado blog, where does Wado fit in all this? I’m not so sure that the image of the line or spectrum between the two polar opposite helps us. I suppose it comes down to the vision and understanding of those who teach it – certainly there is a salutary warning illustrated by the weaknesses of both ‘Fast and Slow burn’.

Perhaps the ‘Fast Burn Slow Burn’ theory can be looked at through another lens, particularly as it relates to Wado?

For example, there is the Omote/Ura viewpoint.

To explain:

In some older forms of Japanese Budo/Bujutsu you have the ‘Omote’ aspect – ‘Omote’ suggests ‘exterior’, think of it like your shopfront. But there is also an ‘Ura’ dimension, an insider knowledge, the reverse of the shopfront, more like, ‘under the counter’, ‘what’s kept in the back room’, not for the eyes of the hoi polloi. The Ura is the refined aspect of the system.

I have heard this spoken about by certain Japanese Wado Sensei, and I have seen specific aspects of what are referred to as ‘Ura waza’, but these seem to range from the more simple hidden implications of techniques, to the seemingly rarefied, esoteric dimension; fogged by oblique references and maddening vagaries, to me they seem like pebbles dropped in a pond, hints rather than concrete actualities.

This of course begs the question; what is the real story of the current iterations of Wado as we know it? I will leave that for you to make your mind up about.

Maybe Wado is about layers?

Problems.

If we return to the original statement, “…all martial arts are about solving the same problem – protection/reaction against human physical aggression”. Ideally the success of the system should be judged by that particular measure, but clearly there is a problem with this, in that empirical data is virtually impossible to find. So how do most people create their own way of judging what is successful and efficient and what isn’t? All we are left with is opinion, which tends to be qualitative rather than quantitative. [5].

Outliers.

Let me throw this one in and risk sabotaging my own theory.

To further complicate things; a good friend of mine is a practitioner of a form of traditional Japanese Budo that that arguably and unashamedly has only one single technique in its syllabus! Yes, only one! My friend is now over 70 years old and has been practising his particular art for most of his adult life. I doubt that for one minute he would consider what he does as ‘fast burn’. I will leave you to work out what his system is, but it is no minor activity, (it is reputed to have over 500,000 practitioners worldwide!)

Tim Shaw

[1] I recently read a comment from an ex-military person who said that relying on unarmed combat in a military situation was ‘an indication that you’d f***ed up’. He said that military personnel relied on their weaponry, if you lost that you were extremely compromised. Also, he added that military personnel worked as a unit and that it is unlikely that a solo unarmed combat scenario would happen. Of course, we know that there are outliers and odd exceptions, but, as a rule… well, it’s not my opinion, it’s his.

After seeing the recent demonstration by North Korean ‘special forces’ in front of their ‘glorious leader’, basically the usual rubbish that you see from the ‘Essential Fakir Handbook’, you have to wonder who these people are kidding? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pv3L2knNodU

It’s just an opinion; not necessarily my opinion; other opinions are available.

[2] ‘Built-in Obsolescence’ Collins Dictionary definition = “the policy of deliberately limiting the life of a product in order to encourage the purchaser to replace it”.

[3] The sons and inheritors of the Tai Chi tradition of Yang Lu-ch’an (1799 – 1872) initially struggled to live up to their father’s punishing and prolonged training regime; Yang Pan-hou (1837 – 1892) tried to run away from home and his brother Yang Chien-hou (1839 – 1917) attempted suicide!

‘Tai-chi Touchstones – Yang Family Secret Transmissions’ Wile D. 1983.