Philosophy

The Ten Ox Herding Pictures.

If you have an interest in Zen and the martial arts, you may or may not have come across the allegory of ‘The Ten Ox Herding Pictures’.

I have been meaning to post on this subject for a while now, and although I am not really a committed Zen Buddhist adherent by any significant measure, I have an outsider’s interest.

Before I get into it in any detail, let me say that I don’t see this allegory as uniquely ‘Zen’, I think it has a wider application, particularly for anyone exploring the conundrum of self-realisation and self-actualisation.

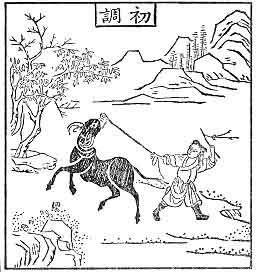

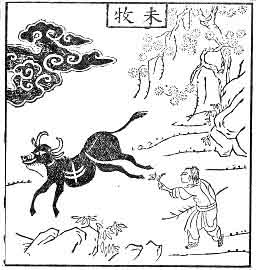

The ten images tell a story of a boy, the ox-herd, and his search for the missing ox and is a metaphor of the search for the true self (the original self); in Buddhist terms, the search for Awakening and the True Reality. The Ox-herd is the smaller self, the ego, who gradually realises that the reality is actually not far away and ultimately contained within him.

History.

Although these images developed a considerable following inside Japan, they are definitely Chinese in origin (as is Zen Buddhism actually). The earliest record of this sequence of images as a metaphor date back to the 11th or 12th century in China. There are usually accompanied by poems, but I would argue that you really don’t need them. At a visual level, you fill in the blanks with your imagination – no need for words – so very ‘Zen’.

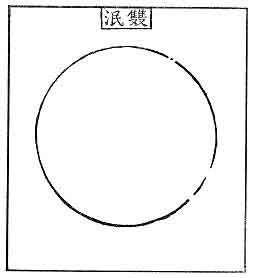

The key differences between the various versions are usually found in the last three pictures. Some versions are content to just complete the series with a blank circle, (which particularly resonates with me), but, arguably, others have a deeper story to tell, making the final picture one of a Buddha or Boddhisatva in the ‘market place’, as if to say, ‘once enlightenment is complete, return to the world, to the busiest place and just ‘be’, amongst the people’. I like that – nobody disappears up into a mountain cave; that is not the place for the sage or the enlightened one. This is a philosophy that is nearer to the Neo-Confucianists, who I believe, have a closer resonance with the martial arts that we know. [1]

A description.

A boy is out in the countryside clearly looking for something. He is sometimes shown holding a kind of tether in his fist. (The wildness of the landscape increases as the narrative develops, as if to underline the difficulty of the quest).

At first he sees the ‘traces’ of the ox (which is sometimes referred to as a bull). Whether this is tracks, or even other things bulls and oxen tend to leave behind, is not really clear.

He catches a glimpse of the untamed ox. This wild spirit shows him a ‘Way’, it’s a hint, but it gives him direction and purpose. This is the beginning of ‘Do’ or ‘Tao’.

The boy pursues the ox, taking to his task with great determination. He finally connects with the animal and manages to attach the tether to it. The hard work begins. It’s a battle between the raw energy of the ox and the willpower and determination of the boy.

The boy is unaware that he is wrestling with his own true nature and trying to bridge the gulf between his uncultured petty ego and the untainted purity of his elemental self. The Buddhists enjoy the use of metaphor to describe this pure self; they are particularly fond of the image of a lotus flower that rises in its purity from the mud of the pond, perfect and unfouled. This is the true self that resides in all of us that remains pure and clean however much with sully it our own self-inflicted contaminants; which, with discipline, can shine forth again.

This is the discipline of the Dojo and the trials of the martial way; whether you want to describe it as a form of self-transformation (internal alchemy), or the ‘forging’ process of Tanren, it is a deep emersion in the greater process of training.

The disciplining of the ox in the various versions usually seems to take a couple of pictures, as if to accentuate the battles that occur between the boy and the ox. Gradually the creature succumbs to harness and becomes placid and resigned to the process. (In some versions the ox starts out pure black in colour and by degrees changes to white).

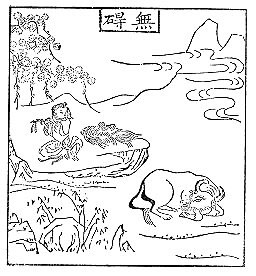

Eventually the boy and the ox establish a harmonious union. The boy is shown riding sedately on the ox’s back, playing his flute, without a care or worry in the world. This is sometimes referred to as ‘coming home’.

In the next pictures the boy and the ox are unconcerned about each other’s presence, there is no battle any more, there is no division; they exist in the same space because there is nothing to separate them; they are one and the same; this is a state of total harmony.

The next image is often described as ‘all forgotten’. The transition is virtually complete; nothing matters. The boys is there, the ox is there, but it is as if nothing is of consequence to either of them; it is just ‘being’.

The final images plunge deeply into the unknown and the esoteric, I don’t pretend to understand them, this is ‘returning to the origin’, whether you want to call this ‘the Great Tao’ or the ‘Universal Divine’ is up to you.

As an aside; many years ago, in my college education, myself and my fellow students were introduced to a retired educationalist, I wish I could remember his name. He was a very strange individual, very calm and patient, he spoke to us as if we were his children, but not in a condescending way. Here was a man who had lived a very full life (I think he’d been in the military during WW2). He encouraged us to ask searching questions, far beyond the limited educational brief. As the discussion opened out we found ourselves questioning the meaning of existence. He talked about ‘answers’ and I asked him, ‘what happens after you find all of the ‘answers?’ He paused slightly and then said, ‘You just… disappear’.

I remember, he smiled and just left that hanging in the air. If I am reading his reply correctly, this was the final message of the ox herding pictures. Here was the blank circle, or the empty landscape.

Leonard Cohen.

This set of pictures had a further reach than most of us realised.

I don’t know how many people are aware of this but singer songwriter Leonard Cohen had a soft spot for the ox herding narrative. I think it is common knowledge that Cohen plunged deeply into the Zen lifestyle, secluding himself in monastic Zen disciplines, indulging in harsh regimes of Zazen (seated meditation).

Some of his most thoughtful and erudite poetry and lyric writing came out of that experience. What ever you think of his vocal style and singing ability there is no getting away from the fact that Cohen was a talent that maybe even eclipsed Dylan. But people seemed not to have noticed a track called ‘The Ballad of the Absent Mare’ which featured on his 1979 album, ‘Recent Songs’.

Canadian singer songwriter Jennifer Warnes recounts how Cohen came over to her house after a meditational retreat, she said, “Leonard had found some old pictures somewhere, they were called ‘The Ten Bulls’, old Japanese woodcuts symbolizing the stages of a monk’s life on the road to enlightenment. These carvings pictured a boy and a bull, the boy losing the bull, the bull hiding, the boy realizing that the bull was nearby all along. There is a struggle, and finally the boy rides the bull into his little village. ‘I thought this would make a great cowboy song,’ he joked.” [2]

Here is a sample of Cohen’s ‘cowboy song’, obviously replace ‘mare’ with ‘ox’ and it’s the same tale:

“Say a prayer for the cowboy, his mare’s run away

And he’ll walk ’til he finds her, his darling, his stray

But the river’s in flood and the roads are awash

And the bridges break up in the panic of loss

And there’s nothing to follow, there’s nowhere to go

She’s gone like the summer, gone like the snow

And the crickets are breaking his heart with their song

As the day caves in and the night is all wrong

Did he dream, was it she who went galloping past?

And bent down the fern, broke open the grass

And printed the mud with the iron and the gold

That he nailed to her feet when he was the lord

And although she goes grazing a minute away

He tracks her all night, he tracks her all day

Oh, blind to her presence, except to compare

His injury here with her punishment there…”

Conclusion.

For this story/allegory to have been around for such a long time says something about its cultural power and its spiritual value. If you take any of the great or iconic stories that have stayed with humanity all the way from antiquity to the present day, their survival is an indication of what they have to teach us, as well as their resonance with the human condition; from the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ (2100 BCE) to ‘Moby Dick’, they present models and narratives that touch and inspire us.

The ox herd pictures could be seen as a compressed version of what Joseph Campbell refers to as the ‘Hero’s journey’ [3], but Campbell’s journey has 17 stages rather than 10. Campbell’s idea is so deeply engrained into western culture that we take it for granted; examples are: Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, ‘Star Wars’, ‘The Matrix’ and even ‘Harry Potter’.

The ox herd pictures are more overtly spiritual, but given their transcendent narrative there is much there to tie in to the martial artist’s personal odyssey, after all, martial arts also aspire to a transcendence, a development of character, a personal alchemy. Let us not pretend that our martial arts journey is devoid of spirituality; by that I don’t mean the ‘Spirituality’ that is allied to organised religion; but instead, the more secular brand, associated with pondering things that are outside and beyond yourself and your whole purpose of being alive and conscious and the meaning of your existence. Buddhism sought to address these puzzles without the need to resort to Gods or supernatural deities (although certain forms of Buddhism never quite shook off the shackles of shamanism, adding things that were never part of the original message).

Of course, martial arts people tend to be very pragmatic and deep meditation on spiritual matters are not to everyone’s taste. My thinking is that while I have no desire to become a Zen Buddhist there is something to gain from exploring the wider cultural context.

But that’s my view – to you, it might just be a load of old Bull.

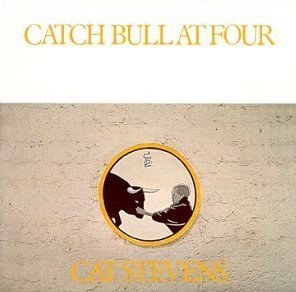

For those of you have an inclination towards trivia; Cat Stevens’ 1972 studio album ‘Catch Bull at Four’ is an obvious reference, which may well have flown right over the head of the average pop music fan of the 1970’s. The album cover makes it very clear.

Tim Shaw

[1] Through personal research and correspondence with experts in the field, I have come to the opinion that works related to the Japanese martial arts that have been pegged as coming from the Zen tradition are actually Neo-Confucian in origin, e.g. Takuan Soho ‘The Unfettered Mind’.

[2] Source: https://www.songfacts.com/facts/leonard-cohen/ballad-of-the-absent-mare

[3] See Joseph Campbell’s ‘Hero with a Thousand Faces’. 1949.

If you are interested in the crossovers between far eastern traditions and philosophy and western psychology, I found that this book has some interesting sections relating to the Ox Herding Pictures; ‘Buddhism and Jungian Psychology’, J. Marvin Spiegelman and Mokusen Miyuki, 1994.

Other references and links:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Bulls

For an excellent description of the series follow this link: https://jessicadavidson.co.uk/2015/10/02/zen-ox-herding-pictures-introduction/

For the full lyrics by Leonard Cohen’s ‘The Ballad of the Absent Mare’ follow this link: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/leonardcohen/balladoftheabsentmare.html

The image featured for ‘Catch Bull at Four’ is sourced from Wikipedia with the appropriate copyright stipulations cited here: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/3/3d/Catch_Bull_at_Four.jpg

Ox herding pictures courtesy of: https://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/mzb/oxherd.htm

Book Review – ‘The Power of Chōwa’.

‘Finding Your Balance Using the Japanese Wisdom of Chōwa’ by Akemi Tanaka.

調和

‘Chōwa’ when broken into its two parts means, ‘Cho’ ‘searching for’ or ‘working at’, establishing ‘Wa’ Harmony (Yes the very same ‘Wa’ 和 as in Wado Ryu!)

Although this book only takes a gentle nod in the direction of Japanese martial arts it is nonetheless a fascinating study and guide for anyone wanting to gain an insight into Japanese culture and society; as well as gaining an understanding of how the all-encompassing Japanese concept of ‘Wa’ operates within Japanese society.

The book is multi-layered; yes it gives a wonderfully unique perspective that crosses between eastern and western cultures but it also delivers incredibly practical and usable advice for modern living.

Akemi Tanaka casts an objective but critical eye on her native Japanese culture; unafraid to outline where she believes that Japanese culture has been somewhat adrift. She includes issues such as feminism and aspects of personal relationships, love, romance and family dynamics. She runs useful comparisons between the western approach and the eastern approach that were particularly enlightening and she includes fascinating Japanese concepts; some of which we encounter within our studies of Japanese Budo.

Her suggestions for focus and tips for modern living were a real breath of fresh air. There are ‘Chōwa lessons’ and suggestions about how to uncomplicate and unclutter your life. For anyone running a hectic household and balancing family life there are some real practical gems.

Akemi Tanaka is open and frank about her personal life and the difficulties she experienced trying to carve her own way in the world. The book crackles with her personal energy and drive; her battles to establish herself and her triumphs through her charity work. She adeptly balances the concept of ‘the self’ and ‘society’, encouraging individuality and creativity.

For me the book unravelled some of the complications I had often puzzled about when dealing with all things Japanese. I had always admired the very practical way that Japanese people dealt with the social conundrum of close living, particularly household living. The book outlined how carefully crafted social conventions acted to oil the wheels of people accustomed to living cheek by jowl. But this is also living Artfully, not just ‘existing’, which is a whole exercise in enrichment and personal fulfilment while still being inside of society and contributing fully.

At the end of the book there is a feeling that author has shared with you something truly personal.

For my mind the book was too short; but then isn’t that always the case with a really good read?

Tim Shaw

The two wheels of a cart.

I had heard a while ago that theory and practice in martial arts were like the two wheels of a cart. One without the other just has you turning around in circles.

It is a convenient metaphor which is designed to make you think about the importance of balance and the integration of mind and body. On one hand, too much theory and it all becomes cerebral, and, on the other hand practice without any theoretical back-up has no depth and would fall apart under pressure.

But here’s another take on it, from the world of Yoga.

Supposing the ratio of theory to practice is not 50/50, and it should be more like 1% theory and 99% practice?

So, for some of the yoga people it’s is very nearly all about doing and not spending so much time thinking about it. I sympathise with this idea, but I feel uneasy about the shrinking of the importance of theory and understanding about what you are doing.

I am sure that I have mentioned in a previous blog post about how the separation of Mind and Body tends to be a very western thing. In eastern thinking the body has an intelligence of its own, over-intellectualisation can be a kind of illness. How many times have we been told, “You’re overthinking it, just do it”? Or, “Don’t think, feel”.

Maybe this points to another way of looking at the diagram above…

Perhaps it’s more like this?

I.e. a huge slice of theory, study, reflection, meditation, intellectual exploration and discussion (still making up only 1%), and an insane amount of physical practice to make up the other 99% to top it off!

Just a thought.

Tim Shaw

Flow

My intentions are to present a book review and at the same time expand it to look at the potential implications for martial artists of this very interesting theme.

For anyone who has not discovered the ideas of psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi get hold of his book. ‘Flow – The Psychology of Happiness’.

This came to me from a very roundabout route. Initially I was curious about Mushin no Waza, (technique of no-mind), a concept many Japanese martial artists are familiar with; but further research lead me on to ‘Flow States’. Musicians might describe this as working ‘in the groove’, or ‘being in the pocket’, psychologist Abraham Maslow called it ‘Peak Experience’, being so fully immersed in what you do, in a state of energised focus almost a reverie. It’s all over the place with sporting activities. Csikszentmihalyi describes it as an ‘optimum experience’.

I should say at this point that it’s nothing mystical or magical, although some would like to describe it as such. As with magic – magic ceases to become magic once it’s explained. I know that once the illusionist’s sleight of hand technique is revealed we all feel a little disappointed and the magical bubble has burst, but if explanation leads to greater understanding it’s a loss worth taking. So it is with Csikszentmihalyi’s book; he unpacks the idea and neatly describes the quality of flow experiences as well explaining the cultural and psychological benefits.

In a nutshell, flow states happen when:

Whatever activity you are engaging in creates a state of total immersion that you almost lose yourself within the activity.

The identifying qualities include:

- Total focus (excluding all external thoughts and distractions).

- The sense of ‘self’ disappears but returns renewed and invigorated once the activity has concluded.

- Time has altered, or becomes irrelevant.

- The activities must have clear goals.

- A sense of control.

- Some immediate feedback.

- Not be too easy, and certainly must not be too hard and entirely out of reach.

Now, I challenge you to look at the above criteria and ask yourself how these line up with what we do in the Dojo. I would bet that some of your most valuable training moments chime with the concepts of the flow state – you have been there. Many of us struggle to rationalise it or find the vocabulary to explain it, but we know that afterwards we have grown.

This ‘growth’ is vital for our development as martial artists and human beings. This is what they mean when they describe martial arts as a spiritual activity; but ‘spiritual’ devoid of religious baggage, but ironically in traditional martial arts there is generally a ritualistic element that sets the scene and promotes the mind-set necessary to enable these flow state opportunities; so I wouldn’t be too quick to dismiss this side of what we do.

Csikszentmihalyi says that flow experiences promote further flow experiences; i.e. once you have had a taste of it you yearn for more, not in a selfish or indulgent way but instead part of you recognises a pathway to human growth and ‘becoming’. We become richer as these unthought-of experiences evolve; we become more complex as human beings.

What is really interesting is that flow states are not judged upon their end results; for example the mountaineer may be motivated by the challenge of reaching the top of the rock face but it is the act of climbing that creates the opportunity and pleasure and puts him in the state of flow and rewards him with the optimal experience that enables him to grow as a human being. So, not all of these experiences are going to be devoid of risk, or even pain and hardship, they may well be part of the package.

Another aspect is that in the middle of these flow experiences there is no space for errant thoughts, if you are doing it right you will have no psychic energy left over to allow your mind to wander. In high level karate competition the competitor who is ‘in the zone’ has no care about what the audience or anyone else might think about his performance or ability; even the referee becomes a distant voice, he is thoroughly engaged in a very fluid scenario.

How many times have you been in the Dojo and found that there is no space in your head for worries about, work, home, money, relationships. You could tell yourself that this ‘pastime’ just gives you an opportunity to run away and bury your head in the sand, but maybe it’s more a case of creating distance to allow fresh perspective.

If Otsuka Sensei saw Budo as a truly global thing, as a vehicle for peace and harmony, then consider this quote from author and philosopher Howard Thurman, and apply it to the idea of Flow;

“Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

Tim Shaw

The Monkey Trap.

This one has been around for a long time, but it’s a very useful model and can be used in many ways.

The Monkey Trap is supposed to be a real thing, a real trap used by primitive tribes to outsmart monkeys. Traditionally the trap features a narrow necked jar which is either tethered to the ground or weighted down. Scattered around the jar are treats the monkey would like but there are more inside. The monkey reaches inside the jar, closes its fist around one of the treats and, with a closed fist it cannot extract its hand past the neck. The monkey is stuck, because of its unwillingness to relinquish its grip on the treat – its own stubbornness, greed and narrow thinking trap it in position. The story was used by Tolstoy in ‘War and Peace’ to describe the French’s unwillingness to discard their loot on the retreat from Moscow. Robert M. Pirsig made use of the same story in ‘Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance’. There’s even an episode of the Simpsons where Homer thinks he can reach inside a vending machine to steal a can of drink, the fire brigade have to free him but a fireman points out to him that all he had to do was let go of the can and his hand would slide out.

Therapists are attracted to this neat little story; it’s a literal example of the pitfalls of not ‘letting go’.

I can think of a number of ways it relates to training. In a way it’s another example of the necessity of ‘emptying your cup’, but, to me, it’s a much more interesting model.

I can see it relating to the problem solving involved in fighting, about the unwillingness to depart from set formulas to solve the problems your opponent is presenting you with. I also see a warning to those of us who have many years behind us in training. I know it’s easy for senior instructors to rest on their laurels and start to believe their own propaganda and particularly to trade upon their association with the stars in the Wado firmament (the ones still with us and the ones departed) but this can have a detrimental effect. In these cases it is possible to get stuck with your hand inside the jar, by being unwilling to let go of perceived status attached to such associations. It’s a matter of judging what’s important to you. By hanging on to such shiny baubles as a form of comfort you miss the opportunity to engage with the wider world and in particular to follow the path of development that got you to where you are in the first place. A monkey stuck in a jar, or a case of wilful arrested development? You decide.

Tim Shaw

Hierarchies.

This is not about politics (though it may start out like that).

It used to be said that if a man is not a Socialist when he is seventeen then he has no heart, if he is still a Socialist when he is fifty he has no head. This does not mean that you are supposed to swerve from left to right as you mature, personally I don’t subscribe to the tribalism of ‘left’ and ‘right’ anymore, they are both two cheeks of the same backside.

Socialists abhor hierarchies, while at the same time feeling it is necessary to utilise them (contradiction?).

Humans by their very nature have a desire to set up hierarchies, even where they do not exist.

Imagine a man who could balance ping pong balls on his nose; would he be content to be the only person who could do that? I doubt it; instead he would present it as a challenge to other jugglers and balancers, who would, inevitably, be able to repeat the trick thus rendering his ‘achievement’ as mediocre. So he then manages to balance two balls on his nose, one on top of the other; seemingly impossible and sets himself up as King of the Ping Pong Ball Balancers! A hierarchy is created – out of nothing. I suppose a good question would be; would ping pong ball balancing put food on the table? There lies another discussion.

In all hierarchies there are winners and losers and people in between and there is supposed to be mobility; not like the old feudal pyramid, more like a ladder.

The people on top give you something to aspire to – unless you are hopelessly stuck on the bottom and then you either resign yourself to failure and give up, or you become a festering ball of resentment, which is not healthy.

These people on the very top are there for a reason. To briefly examine that, it might be worth making a quick reference to French and Raven’s six bases of power. This was formulated in 1959 by social psychologists John French and Bertram Raven.

- Base 1. Legitimate power (or inherited power) – the person in charge has the right to be there.

- Base 2. Reward – You are rewarded by letting that person assume the position.

- Base 3. Expert – That person is the most skilled, so they should be on top.

- Base 4. Referent – the person is seen as the most appealing option because of their worthiness.

- Base 5. Coercive – The fear of punishment keeps this person on top.

- Base 6. Informational – (added later and very apt to today) The person on top controls the information that people need to get stuff done.

Every boss I have ever met considers that ‘Base 3’ is why they are there, with a liberal dose of ‘Base 4’ of course.

Everything you have ever done and gained a feeling of positive achievement from existed within a hierarchy, and that of course includes martial arts training. If the hierarchy is working well you have confidence in the system because opportunities arise from engaging in it, you reap the rewards of your own efforts.

Ambitious people tend to form their own hierarchies and strive to become king of their own tiny little hill, and we see that in the martial arts all the time – everyone wants to King of the Ping Pong Ball Balancers.

Tim Shaw

Going to the extreme.

Sigmund Freud, Carl Gustav Jung & Ueshiba Morihei.

Recently I have been reading a biography of Swiss Psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung and something just jumped off the page at me.

Jung suffered a prolonged mental breakdown between the years 1913 to 1918, but what happened to him during those years did not drag him down into an irrecoverable pit of despair and degeneration (as had happened with Nietzsche), he instead used his own condition to explore the workings of his mind, and in the process of doing so discovered significant and profound insight that he then wanted to share with the world, an unfolding of the mind. To me this sounded familiar.

In 1925 an energetic and obsessed Japanese martial artist called Ueshiba Morihei also underwent a significant change. In his culture it was described as an enlightenment; an extreme physical and psychological episode, during which certain ‘realities’ were revealed to him, motivating him to disseminate the message to all Mankind – the message was Aikido.

Henri Ellenberger wrote about such episodes in his 1970 book, ‘The Discovery of the Unconscious’, he described them as, ‘Creative illnesses’. Interestingly Sigmund Freud (Jung’s mentor) also underwent a similar breakdown and revelation. Amazingly, all three of these men experienced these episodes at the same time in their lives, between the ages of 38 and 43. To me this all adds up.

There is a common process here; all of these individuals had gone for a total emersion into their chosen disciplines; they had all stretched the boundaries further than anyone had ever gone before. In Japan this kind of process usually involved a retreat into the isolated wilds, which included meditation (introspection) and physical hardships.

If you look for it this pattern is all over the place; it’s a human phenomenon, part of what Jung was to call the ‘collective unconscious’.

Iconic American musicians of the early 20th century retreated to the ‘Woodshed’; Robert Johnson had his enlightenment at the crossroads at midnight when he ‘sold his soul to the Devil’.

The ultimate model of near breakdown and Enlightenment is the Buddha, but there have been many other figures from different traditions. I’m not so sure it all ended up in the right area, after all we only hear of the successes, never the failures. Or we hear of historical examples who have been adopted as successes, but whose lives, when looked at through modern lenses, may well tell another story – I am thinking of St Teresa of Avila as one prime example; I wonder what a Jungian or Freudian psychoanalyst would have made of her?

Tim Shaw

Order and Chaos – Why it Matters for Martial Artists.

I have recently been reading Jordan B. Peterson’s ’12 Rules for Life’ and I have watched a few of his lectures online. Peterson is a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Toronto and has some quite interesting things to say. His views on Order and Chaos chimed with something that had been going through my head for a long time.

Way back when I was a university student I attended a lecture on ‘Apollo and Dionysus’ that got me thinking. As you may know Dionysus (Bacchus) was the god of wine, darkness and of wild hedonism and chaos, a real fun guy. While Apollo was the god of reason, order, light, a total bore; the ‘Captain America’ of superhero gods. The logic of this was creating models of duality; virtually the same as the Taoist Yin and Yang, which is a simple circular motif of two halves, one black, one white separated by a curving line.

For the purpose of explanation ‘Order’ and ‘Chaos’ are the most useful terms.

The realm of Order is everything we know; where rules are followed, structures are in place, it is comfort and to some degree also complacency (but more of that later). Whereas Chaos is unpredictability, it is the gaps between the laws that protect us; it is what happens when things break down, small scale and large scale, ultimately expressing complete anarchy.

I witnessed a minor version of chaos recently on a Tube train in London late at night. The majority of the passengers were abiding in the world of order, following social protocols, but a small noisy part of drunken people came into the carriage, not following the rules; nothing significant happened but to me they were like illogical, fuzzy minor condensed version of chaos, anything could have happened, the potential was there, just by the presence of chaos.

Peterson says that it is healthy to not just acknowledge chaos but also to engage with it. The complacency that comes with order ultimately would just result in you staying in your room. Progress comes from stepping out into the world and moving away from your comfort zone and putting yourself in more unpredictable positions (chaos).

Look at what we do in martial arts training.

In a very simplistic way we discipline ourselves through the most orderly, regimented environments imaginable, we convince ourselves we are training for chaos, and, in a way we are, but not necessarily in the way we think. Violence is an extreme embodiment of chaos and should not be taken lightly, but it is a complex issue full of wild variables. Just think of one of the worst scenarios; multiple attackers, unfamiliar environment, motivations unclear, limited light, all parties befuddled or fuelled by alcohol – it’s a mess. But this is an extreme.

Let’s go back into the Dojo; here are some examples of engaging with chaos that lead you towards more positive outcomes.

It starts out very simply, where you pressure-test your training in more manageable ways.

In a formal setting there is scope for tiptoeing into the chaos zone; e.g. if you work kihon gumite but the Torime doesn’t know what the second attack is; you could gamble, but it’s better to see if you can resolve the problem through your conditioned training.

Every time you take part in sparring; there are rules but essentially you are engaging with controlled chaos.

In my Dojo we have been working for a long time now on devising new ways of pressure-testing our reactions to attacks, creating opportunities to really work our conditioned responses, one method we use is called Ohyo Henka Dousa, a method of continual engagement with an attacker’s intent.

To go back to the Yin Yang symbol, Peterson says that the curving line between the two areas is a line that we should tiptoe along, occasionally deliberately allowing our foot to stray into the zone of chaos and very much acknowledging that it is part of our lives – something that can be used for good.

Tim Shaw

Feedback (part 2).

What information is your body giving you? Are you truly your own best critic?

When we are desperately trying to improve our technique we tend to rely on instruction and then practice augmented by helpful feedback, usually from our Sensei.

But perhaps there are other ways to gain even better quality feedback and perhaps ‘feedback’ is not as simple as it first appears.

If we were to just look at it from the area of kata performance; if you are fortunate enough to have mirrors in your training space (as we do at Shikukai Chelmsford) then reviewing your technique in a mirror can be really helpful. But there are some down sides. One is that I am certain when we use the mirror we do a lot of self-editing, we choose to see what we want to see; viewpoint angle etc.

The other down-side is that we externalise the kata, instead of internalising it. When referring to a mirror we are projecting ourselves and observing the projection; this creates a tiny but significant reality gap. It is possible that in reviewing the information we get from the mirror we get useful information about our external form (our ability to make shapes, or our speed – or lack of speed.) but we lose sight of our internal connections, such as our lines of tension, connectivity and relays. We shift our focus away from the inner feel of what we are doing at the expense of a particular kind of visual aesthetic.

You can test this for yourself: take a small section of a kata, perform the section once normally (observe yourself in a mirror if you like) then do the same section with your eyes closed. If you are in tune with your body you will find the difference quite shocking.

Another product of this ‘externalising’ in kata worth examining is how easy it is to rely on visual external cues to keep you on track throughout the performance; usually this is about orientation. I will give an example from Pinan Nidan: if I tell myself that near the beginning of the kata is a run of three Jodan Nagashi Uke and near the end a similar run of three techniques but this time Junzuki AND that on the first run of three I am always going towards the Kamidana, but on the second run of three I will be heading in the direction of the Dojo door, I come to rely almost entirely on these landmarks for orientation, thus I have gone too deeply into externalising my kata; it happens in a landscape instead of in my body. Where this can seriously mess you up is if you have to perform in a high pressure environment (e.g. contest, grading or demonstration) your familiar ‘landscape’ that you relied heavily upon has disappeared, only to be replaced by a very different, often much harsher landscape, one frequently inhabited by a much more critical audience. A partial antidote to this is to always try and face different directions in your home Dojo; but really this is just a sticking plaster.

Another quirky odd anomaly I have discovered when working in a Dojo with mirrors is that during sparring I sometimes find myself using the mirror to gain an almost split-screen stereoscopic view of what my opponent is up to, tiny visual clues coming from a different viewpoint, but it’s dangerous splitting your attention like that and on more than one occasion I have been caught out, so much so that I now try and stay with my back to the mirror when fighting.

Another visual feedback method is video. This can be helpful in kata and individual kihon. In kihon try filming two students side by side to compare their technical differences or similarities. If you have the set-up you could film techniques from above (flaws in Nagashizuki show up particularly well).

There are some subtle and profound issues surrounding this idea of ‘internalising’ ‘externalising’, some of it to do with the origin of movement and the direction (and state) of the mind, but short blog posts like this are perhaps not the place for exploring these issues – the real place for exploring them is in your body.

Tim Shaw

Book Review: ‘The Path’ Professor Michael Puett & Christine Gross-Loh.

Not a book about martial arts at all, but one that relates to the martial arts.

Professor Michael Puett is a Harvard professor who lectures on oriental philosophy. His classes are oversubscribed and often host around 700 students (how is that even possible?). The popularity of the lectures comes out of the promise that these lectures will change your life!

Puett repackages the teachings of Confucius, Mencius and Lao Tzu, etc. for a modern age and presents the ideas of these ancient Chinese teachers in a transformative way. The book contains material from the lectures compressed into themes and chapters making it all very accessible.

Confucians and Neo-Confucians have always had bad press because they have been blamed for Chinese rigid class and social structures, reinforcing gender discrimination and even promoting insular selfishness within the society. This is all a bit lazy for me. The rigidity of the last years of the old Chinese national structure, pre-Mao, was epitomised by the Civil Service exams in which the applicants were expected to memorise huge amounts of the ‘Classics’ to demonstrate their worthiness. Although this served the Chinese well in the earlier centuries the decaying husk it turned in to just proves how things go when they develop into ‘institutions’ and lose their meaning becoming fossilised relics of what may have originally been fresh intelligent philosophies on how to live the good life.

This re-packaging of ancient Chinese philosophies gives a refreshing perspective on ideas that are woven into most oriental martial arts and we can easily discover these ideas within Japanese Budo. Have you ever wondered about how ritual is used within Japanese martial traditions? Puett’s unpicking of the importance of ritual in Confucius’s ideas is a revitalising breath of fresh air that blows away the fustiness of institutionalised ‘rites’.

Mencius (372 BCE – 289 BCE) comes across as the voice of reason and has always been a particular touchstone of mine. His views on humanity, development, growth and spiritual cultivation all fit in neatly with the ideals of the man of Budo.

Puett challenges us to think differently, he questions some of our very basic assertions and asks us to re-frame our references; this was refreshing and made me think that perhaps some of my own assumptions need a more rigorous grilling.

The section on Chi is a real myth buster.

His explanation of spontaneity and how it can reach a high level only after prolonged prior training follows the exact model that most martial artists adhere to.

It is a very thought-provoking read and deliberately breaks free from entrenched ideas about how with think the world should work. Definitely worth more than one read-through.

Tim Shaw