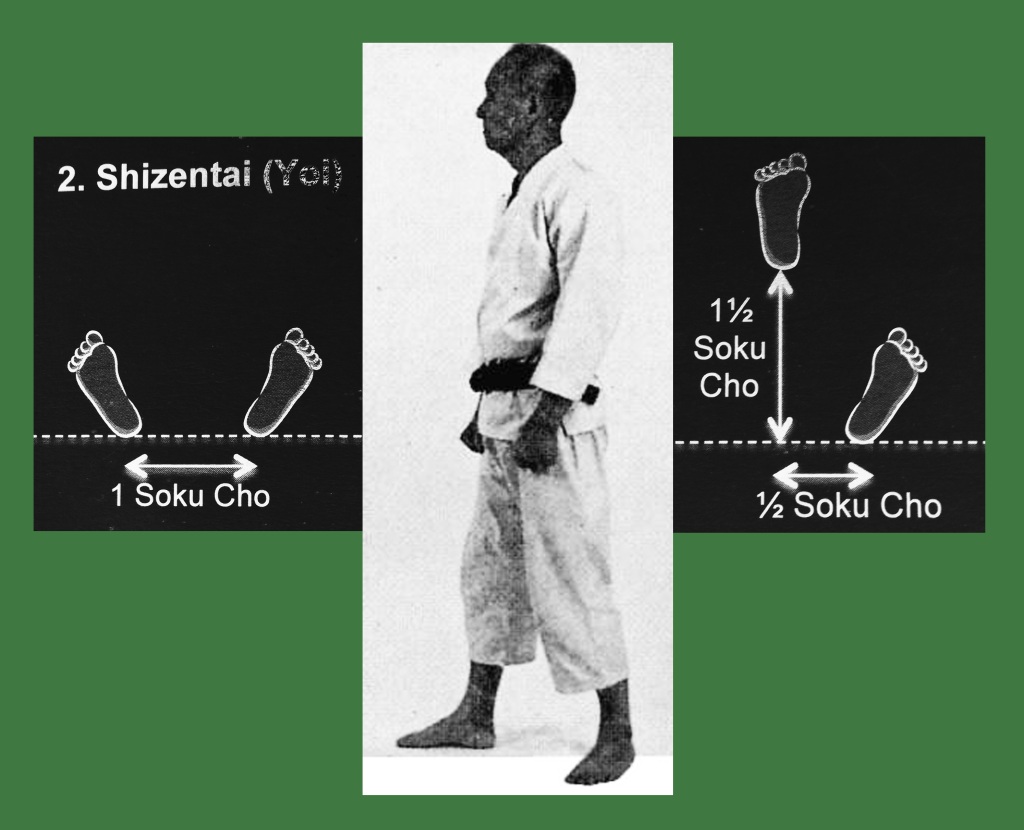

Shizentai.

Look through most Wado syllabus books and a few text books and you are bound to see a list of stances used in Wado karate; usually with a helpful diagram showing the foot positions.

One of the most basic positions is Shizentai; a seemingly benign ‘ready’ position with the feet apart and hands hanging naturally, but in fists. It is referred to as ‘natural stance’, mostly out of convenience; but as most of us are aware, the ‘tai’ part, usually indicated ‘body’, so ‘natural body’ would be a more accurate fit. [1].

In this particular post I want to explore Shizentai beyond the idea of it being a mere foot position, or something that signifies ‘ready’ (‘yoi’). There are more dimensions to this than meets the eye.

Let me split this into two factors:

- Firstly, the very practical, physical/martial manifestation and operational aspects.

- Secondly, the philosophical dimension. Shizentai as an aspiration, or a state of Mind.

Practicalities.

The physical manifestation of Shizentai as a stance, posture or attitude seems to suggest a kind of neutrality; this is misleading, because neutrality implies inertia, or being fixed in a kind of no-man’s land. The posture may seem to indicate that the person is switched off, or, at worst, an embodiment of indecisiveness.

No, instead, I would suggest that this ‘neutrality’ is the void out of which all possibilities spring. It is the conduit for all potential action.

Isn’t it interesting that in Wado any obvious tensing to set up Shizentai/Yoi is frowned upon; whereas other styles seem to insist upon a form of clenching and deliberate and very visual energising, particularly of the arms? As Wado observers, if we ever see that happening our inevitable knee-jerk is to say, ‘this is not Wado’, or at least that is my instinct, others may disagree.

Similarly, in the Wado Shizentai; the face gives nothing away, the breathing is calm and natural, nothing is forced.

In addition, I would say that in striking a pose, an attitude, a posture, you are transmitting information to your opponent. But there is a flip-side to this – the attitude or posture you take can also deny the opponent valuable information. You can unsettle your opponent and mentally destabilise him (kuzushi at the mental level, before any physical contact has happened). [2]

Shizentai as a Natural State – the philosophical dimension.

I mentioned above that Shizentai, the natural body goes beyond the corporeal and becomes a high-level aspiration; something we practice and aim to achieve, even though our accumulated habits are always there to trip us up.

In the West we seem to be very hung up on the duality of Mind and Body; but Japanese thinking is much more flexible and often sees the Mind/Body as a single entity, which helps to support the idea that Shizentai is a full-on holistic state, not something segmented and shoved into categories for convenience.

This helps us to understand Shizentai as a ‘Natural State’ rather than just a ‘Natural Body(stance)’.

But what is this naturalness that we should be reaching for?

Sometimes, to pin a term down, it is useful to examine what it is not, what its opposite is. The opposite of this natural state at a human level is something that is ‘artificial’, ‘forced’, ‘affected’, or ‘disingenuous’. To be in a pure Natural State means to be true to your nature; this doesn’t mean just ‘being you’, because, in some ways we are made up of all our accumulated experiences and the consequences of our past actions, both good and bad. Instead, this is another aspect of self-perfection, a stripping away of the unnecessary add-ons and returning to your true, original nature; the type of aspiration that would chime with the objectives of the Taoists, Buddhists and Neo-Confucians.

Although at this point and to give a balanced picture I think it only fair to say that Natural Action also includes the option for inaction. Sometimes the most appropriate and natural thing is to do nothing. [3]

Naturalness as it appears in other systems.

In the early days of the formation of Judo the Japanese pioneers were really keen to hold on to their philosophical principles, which clearly originated in their antecedent systems, the Koryu. Shizentai was a key part of their practical and ethical base. [4] In Judo, at a practical level, Shizentai was the axial position from which all postures, opportunities and techniques emanated. Naturalness was a prerequisite of a kind of formless flow, a poetic and pure spontaneity that was essential for Judo at its highest level.

Within Wado?

When gathering my thought for this post I was reminded of the words of a particular Japanese Wado Sensei. It must have been about 1977 when he told us that at a grading or competition he could tell the quality and skill level of the student by the way they walked on to the performance area, before they even made a move. Now, I don’t think he was talking about the exaggerated formalised striding out you see with modern kata competitors, which again, is the complete opposite of ‘natural’ and is obviously something borrowed from gymnastics. I think what he was referring to was the micro-clues that are the product of a natural and unforced confidence and composure. For him the student’s ability just shone through, even before a punch was thrown or an active stance was taken.

This had me reflecting on the performances of the first and second grandmasters of Wado, particularly in paired kata. On film, what is noticeable is their apparent casualness when facing an opponent. Although both were filmed in their senior years, they each displayed a natural and calm composure with no need for drama. This is particularly noticeable in Tanto Dori (knife defence), where, by necessity, and, as if to emphasise the point, the hands are dropped, which for me belies the very essence of Shizentai. There is no need to turn the volume up to eleven, no stamping of the feet or huffing and puffing; certainly, it is not a crowd pleaser… it just is, as it is.

As a final thought, I would say to those who think that Shizentai has no guard. At the highest level, there is no guard, because everything is ‘guard’.

Tim Shaw

[1] The stance is sometimes called, ‘hachijidachi’, or ‘figure eight stance’, because the shape of the feet position suggests the Japanese character for the number eight, 八.

[2] Japanese swordsmanship has this woven into the practice. At its simplest form the posture can set up a kill zone, which may of may not entice the opponent into it – the problem is his, if he is forced to engage. Or even the posture can hide vital pieces of information, like the length or nature of the weapon he is about to face, making it incredibly difficult to take the correct distance; which may have potentially fatal consequences.

[3] The Chinese philosopher Mencius (372 BCE – 289 BCE) told this story, “Among the people of the state of Song there was one who, concerned lest his grain not grow, pulled on it. Wearily, he returned home, and said to his family, ‘Today I am worn out. I helped the grain to grow.’ His son rushed out and looked at it. The grain was withered”. In the farmer’s enthusiasm to enhance the growth of his crops he went beyond the bounds of Nature. Clearly his best course of action was to do nothing.

[4] See the writings of Koizumi Gunji, particularly, ‘My study of Judo: The principles and the technical fundamentals’ (1960).