principles

Books for martial artists. Part 2. East meets West, and West meets itself.

In this second part I want to dip a toe into the way ideas originating in the far eastern martial arts migrated to the west and then morphed into something else.

Also, whether the current brands of ‘self-help’ publications may or may not have something to offer us as martial artists.

Sun Tzu – The Art of War.

If anything can be clearly categorised as being a ‘martial arts’ book it has to be Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Said to have been written around 500 BCE, this short text contains a wealth of martial knowledge and strategy. [1] The beauty of the book is that it is broad in its application and scope, yet detailed enough to pick out examples for reflection; and it plays with the conceit of being applicable to individual combat and battles involving large numbers.

People in the west have been aware of this book for as long as there has been an interest in orientalism, and inevitably it has been appropriated by the business world. So many spin-offs telling us how Sun Tzu’s book can be applied to the cut and thrust of the high-powered boardroom -everyone is looking for an edge. Titles appeared like, ‘Art of War for Executives’, ‘Sun Tzu – Strategies for Marketing’, etc, etc.

Musashi Miyamoto – ‘The Book of Five Rings’.

Musashi’s terse book on strategy and fighting suffered a similar fate to Sun Tzu. I have mixed feelings about the Book of Five Rings. At least one Japanese Sensei I have spoken to has been puzzled about Musashi’s status, as in, ‘why this guy?’, ‘Why does this dubious character deserve so much attention, when there are so many more elevated examples… Katsu Kaishu was an amazing model, yet nobody talks about him?’.

I have seen ‘the entrepreneurs guide to the Book of Five Rings’ and others have tried to piggyback on this book of ‘wisdom’.

Musashi was a product of his age, and in terms of Darwinian principles, managed to stay alive through sheer cunning and an unorthodox approach (though, what was orthodoxy in that age is very fluid. 16th century Japan was like the wild west). Again, you have to understand the context.

A quick note on the ‘Warrior’ mentality.

Excuse me for my cynicism here but nothing grinds my gears like the overuse and appropriation of the word ‘warrior’.

As a ‘meme’ on the Internet all these ‘warrior quotes’ are guaranteed to cause me to gnash my teeth in anger and frustration.

Musashi ‘quotes’ abound (which end up as not ‘quotes’ at all, just some made up cobblers nicked from another source). [2]

Just what do people mean when they refer to ‘Warriors’ anyway? Are we talking about the modern context; the professional soldier? If so, the gulf between that model and the model presented by someone like Homer when he introduced us to Achilles and Hector, or, in Japan the stories told about Tsukahara Bokuden (1489 – 1571) [3] is just too huge a gulf to be bridged; different worlds, different mentality, different technology. Unfortunately, the romantic appeal of BEING a ‘warrior’ attracts precisely the same people who lack all the idealised and fictional attributes of so-called warriordom, a domain for fantasists and keyboard heroes. Sad, but true.

To return to books.

‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’

I know that I have mentioned in a blog post previously about Inazo Nitobe’s ‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’ book. Essentially it is a confection running an agenda, in that Nitobe wanted to build a cultural bridge between Japan and the west with a distinctly Christian bias (he was a Quaker). He created an overblown link between the romanticised ideal of medieval chivalry and an equally fictionalised picture of the ‘code of the Samurai’; as such, in a nutshell, ‘Bushido’ was a modern invention. I’m sorry, but somebody had to say it.

‘Zen in the Art of Archery’.

Although this book has been influential for some time it also suffers criticism not dissimilar to Nitobe’s book. Eugen Herrigel, wrote the book after his experiences with a Japanese Kyudo (archery) teacher, Awa Kenzo. Herrigel was teaching philosophy in Japan between 1924 to 1929, the book was published in Germany in 1948. My view is that Herrigel’s achievement in writing this very short book was that he introduced the element of spirituality linked to Japanese martial training to western thinking. Although I feel a need to offer a disclaimer here… Herrigel has taken some flak (posthumously, he died in 1955); intellectual big guns like Arthur Koestler and Gershom Scholem pointed out that in the book Herrigel was spouting ideas that came from his connections with the Nazi party.

Yamada Shoji in his book ‘Shots in the Dark’ suggests that Herrigel had got it all wrong and that the ‘Zen’ element was embroidered into the story. Yamada also tells us that conversations Herrigel had with Awa Sensei were either misunderstood or simply didn’t happen.

The title alone spawned homages to Herrigel’s book – ‘Zen and the Art of Motocycle Maintenance’ comes to mind. Also, in a previous post I mentioned ‘The Inner Game of Tennis’ by Gallwey; it was Herrigel’s book that inspired Gallwey’s thinking; so, let’s not give Eugen Herrigel too hard a time.

Western books that may be relevant.

Rick Fields books are quite interesting, one in particular. Don’t be mislead by the title (based on what I’ve said above) but ‘The Code of the Warrior – in History, Myth and Everyday Life’ is a really engaging read. Fields gives us a potted history of the urge to take up arms, from the prehistoric times through to Native American culture and even a chapter on ‘The Warrior and the Businessperson’, looking at Japanese business methods and their link to samurai mentality.

Rick Fields other books have a more spiritual dimension and tend to look dated and New Age in their outlook, (written in the 1980’s); ‘Chop Wood, Carry Water’ has a clearly Buddhist vibe with a touch of the ‘Iron John’ about it. [4]

Self Help books.

Although not specific to martial arts training the so-called ‘Self Help’ book explosion may have some useful cross-overs. I had previously written a book review for ‘The Power of Chowa – Finding Your Balance using the Japanese Wisdom of Chowa’ by Akemi Tanaka. There are other books encouraging us to lead better lives that have a base in Japanese thinking, but Tanaka’s book has a clear objective of helping people to restore a meaningful balance in their lives.

I know other martial artists I have spoken to have found certain authors useful in contributing to the spiritual side of their martial arts experience. To mention a few:

- Stephen Covey, author of ‘Seven Habits of Highly Effective People’. I haven’t read it but I did read his book, ‘Principle Centred Leadership’. My takeaway from that was how much Covey was borrowing from other sources – some stand-out examples seem to come from Taoism; but useful nevertheless.

- A raspberry from me for Richard Bandler, I am suspicious of anything from him and his followers; he is one of the originators of Neuro-linguistic programming (NLP). It is, essentially pseudoscience and latest neurological research suggests that Bandler is barking up the wrong tree.

- Following a Zenic direction, Eckhart Tolle’s descriptions of the benefits of ‘living in the Now’ are worth taking a look at (though avoid the audiobook version of ‘The Power of Now’, unless you suffer from insomnia; his voice is one continuous flat drone).

- Followers of this blog will perhaps have realised that I have a lot of time for Jordan B. Peterson; however, only three books have been published [5], but the online lectures are solid gold. Peterson has some interesting thoughts on serious martial artists, who he talks about in his references to the Jungian concept of the Shadow.

The Dark Arts.

This post would not be complete without mentioning what I have called ‘the Dark Arts’. These are almost exclusively western in origin. I am not really sure where I stand on the efficacy or even the morality of these publications, but here is a list:

- ‘The Prince’, Niccolo Machiavelli 1532. The vulpine nature of Machiavelli just oozes off every page. He was a master of deception and treachery, a minor diplomat in the Florentine Republic. ‘The Prince’ is a masterwork for anyone who wants to succeed at any cost. But you might want to wash your hands afterwards.

- ‘The Art of Worldly Wisdom’ Baltasar Gracian 1647. Similar in nature to ‘The Prince’. Gracian was a Spanish Jesuit priest. Winston Churchill was said to be inspired by this book. It is dedicated to the arts of ingratiation, deception and the cunning climb to power. Just as apt today as it was then.

- Contemporary writer Robert Greene is perhaps the inheritor of Machiavelli and Gracian; in fact, he borrows heavily and unashamedly from these sources. He initially shot to fame with his 1998 book ‘The 48 Laws of Power’. The titles of his books always suggest to me as a mandate for roguery and look to all intent and purposes like a villain’s charter, as an example; ‘The Art of Seduction’ 2001 and ‘The Laws of Human Nature’ 2018. This put me off, that, and a conversation with my barber who seemed to enjoy the salacious nature of Greene’s ‘words of wisdom’. But I listened to Greene interviewed on a podcast and my view changed. Having now read ‘The 48 Laws of Power’ I realised that Greene wrote this almost from a victim’s perspective and I saw in it mistakes I had made in my past and have since bitterly regretted. A useful and humbling experience. There is more humanity in this book than I initially assumed – but also a good measure of naked ambition and dirty dealings, if you like that sort of thing.

Clearly this is not a comprehensive list of everything out there, just things I wanted to share. I think there are many martial arts people who want to look beyond the physicality of their discipline and have an urge to find a wider meaning to their efforts – which is entirely in line with the broader scope of Budo, as envisioned by Japanese masters like Otsuka Hironori, Kano Jigoro and Ueshiba Morihei.

Follow your curiosity and enjoy your reading.

Tim Shaw

[1] The Penguin ‘Great Ideas’ edition is a mere 100 pages in length, with each page consisting of very short stanzas – a very simple read.

[2] The only time I felt inclined to use a ‘warrior based’ quote was a very apt one that I quite liked, “The nation that will insist on drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking done by cowards”. Thucydides.

[3] Bruce Lee’s ‘Fighting without fighting’ scene in ‘Enter the Dragon’ was stolen straight from stories about Tsukahara Bokuden.

[4] ‘Iron John – A Book About Men’ by Robert Bly. The author attempted to rescue the soul of masculinity, this was intended as an antidote to the excesses of feminism (well this was 1990!) but it was ridiculed and derided in all quarters as it became associated with all the ‘sweat lodge’, ‘male bonding’ razzamatazz, that might have been quite benign, although misguided, but quickly turned into something darker.

[5]. Jordan B. Peterson books; ‘Maps and Meaning’ (a demanding read), ‘Twelve Rules for Life’, (much easier to read and really relevant) and the latest book, ‘Beyond Order’, also good.

Image: ‘St Jerome in his study’ by Albrecht Dürer 1514. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

How detailed is your Wado map?

How confident are you about what you know of your system, the discipline you have chosen to study? Are you comfortable with the information you currently have to hand? Do you think you understand the roadmap of that developing knowledge, and is its trajectory obvious and predictable?

Okay, so, I accept that any Wado practitioner reading this might well be at very different points in their journey; some may be just beginning their study, others might be senior practitioners with many years behind them, but the ideas I am going to put forward I am fairly sure would benefit all – or at least stop and make you think. That’s the plan anyway.

Maps.

I am going to start with the broader idea, something I heard a little while ago. There is a theory that we all keep a complete map of the world within our own heads – a personal hardwired version like Google Satellite, Street View and Maps. When I first heard this, I was sceptical.

While I am fully aware that the human brain is perhaps the most complex thing on the planet but really this seemed a bit too far-fetched. But, it is true. That mess of grey matter that sits between our ears that has no awareness of itself outside of its own input devices – our senses, can really do all that, and more!

This amazing mapping, navigation device does not just include places, it also acts as our own personal encyclopaedia, with just about everything there is to be referenced. I use the word ‘referenced’ in a very deliberate way because the reality is that ‘references’ are about all we get.

To explain; while we have this map/encyclopaedia in our head most of this information is patchy and, in many cases, extremely low-resolution. The truth is, we have low-resolution representations of the majority of things we think we know.

Examples:

- Ask yourself about a random country in the world; say, Vietnam? Can you point to it on a map? Probably, but what else can your personalised encyclopaedia tell you? History, culture, language, currency? Unless you know the country very well through direct experience your knowledge will be sketchy, very low-resolution.

- Another couple of words; ‘Steam Train’. To communicate your understanding of this mode of transport, you might draw me a picture of a steam train, complete with funnel and wheels and a cab, all very ‘Thomas the Tank Engine’ – but unless you are an insanely enthusiastic trainspotter with qualifications in engineering and skills in mechanical draughtsmanship, I am not going to be convinced that you really understand a steam train, it will be extremely low-resolution.

Okay, so there are things we might be VERY knowledgeable about (or THINK we are), but the reality of our ‘wired-in’ intelligence and retrieval system (brain) is that it is in a state of constant update, or at least it should be. The truth is that (hopefully) more depth of information is being added and redundant (false) files are being deleted or replaced and new entries or categories are being added.

In some areas, people actually choose not to update their maps and files, this is often found when people become entrenched in areas like politics. Clearly, individuals can be so profoundly tribal in their political beliefs that even in the face of irrefutable evidence they will argue that black is white. But that’s their problem.

How about Wado (or any martial arts system)?

All of the above can be applied to our understanding of Wado karate.

I think it’s a case of being totally honest with yourself; particularly those who have been on this pathway a long time. Come on, do you really believe the same things that you did twenty years ago? How have your files been updated?

An example:

I came to the conclusion a long time back that just about everyone I knew in the martial arts continued their training for completely different reasons than those they started with. It might have been that they initially wanted to build confidence; they were fearful about their ability to protect themselves; but then, over time, their maps changed, their references became more sophisticated, more nuanced and they found something new, something of substance. I can’t get into describing what that is in this post, I don’t have the space; (in some ways I explored this idea in my blog post ‘Martial Arts training and the value of finding your Tribe.’).

Your Wado map.

For every student of Wado karate your initial ‘map’ is usually found in the pages of your syllabus book. This map expands as you move through the grades. Although, I must say, the reality is, it’s not an easily accessible map because it is mostly written in a different language.

But it would be naïve to assume that when we have completed the book we have mastered the system, it doesn’t work like that. The syllabus is a very low-resolution representation of the system; really, it’s a loose framework designed for convenience. In addition, ‘knowing’ the book, with its Kihon, Kata and Kumite doesn’t guarantee you can actually do it; and doing it doesn’t mean you can apply it. Imagine a musician who can read sheet music but can’t play an instrument, or who can play the music accurately but cannot improvise!

The downside of the syllabus book.

In Wado I don’t think reliance on the syllabus book is particularly helpful; it’s a pretty poor map. For me it’s too linear. For systems other than Wado it might easily describe the structure in a straightforward and accurate way, but within Wado karate it only takes you so far in understanding the true nature of this very unique Japanese Budo system. In fact, I would go so far as to say that if the book is the only model/access route, it will ultimately lead you down a dead end. [1]

A different map.

In some of my more recent teaching seminars I have presented a completely different map; a pictorial diagram that I think enables Wado students to navigate a more useful and meaningful way of understanding Wado – but a blog post like this is not the place to share this idea; besides, it is still a work in progress, as it should be. [2]

Expanding the map or increasing the resolution?

I think it is too easy to misread what I mean by developing or expanding the map. I don’t think that the Wado map should be seen as a kind of growing, territorial colonialisation, similar to a video game like ‘The Settlers’ or ‘Minecraft’ where from a tiny localised centre you keep occupying new territory and building new structures; that would be like adding extra pages on the end of the syllabus book.

To give a concrete example: Otsuka Sensei was quite content with the idea of nine core solo kata, anything beyond the apex kata of Chinto was classified as ‘extra’. [3]

Paired kata are perhaps another story. If you take them on face value, they are legion! But to focus on their bewildering number is perhaps missing the point.

I speculate that with the paired kata there is a hidden map lurking beneath the seemingly complicated map which features, for example; the ten Kihon Gumite, the thirty-six Kumite Gata, twenty-four Ura no Kumite and all the rest. The clue is when you acknowledge the reality that none of these paired kata contradict the core principles, and it is these core principles that are the real map, the one skulking underneath, and, in content, the ‘Principle Map’ is not such a huge numerical challenge.

The most valuable approach is not necessarily to expand the territory, but to increase the resolution. The territory might well push beyond its boundaries but only in a natural, unforced way, an organic by-product of more defined and focussed examination. The real payback is in the more granular exploration of areas you already think you know.

‘Low-resolution’ has its uses.

Low-resolution thinking is natural to us, it’s the very basic of what we needed to survive and has been with us for tens of thousands of years. But what might have been paramount for hunter-gatherers has now slipped down our list of priorities – I mean who needs to clutter up their thinking about what they might have had for breakfast when they are being chased by a sabre-tooth cat? A boost of adrenalin and the most basic info about an escape route should be enough!

What does ‘increasing the resolution’ mean for your Wado?

Let me start with what it does NOT mean:

- It does not mean knowing more and more about less and less.

- It does not mean you become a slave to detail, which, if taken to its extreme can result in you looking like an obsessive dilettante, all ‘head knowledge’ and no practical/physical skills. [4]

- It does not limit your thinking by allowing you to assume you have it all pinned down. Actually, the reverse should happen; your mind continues to expand.

What it DOES mean is:

- The more granular your understanding the more you appreciate the relationships between the various parts of your Wado map, the underpinning logic.

- This increased resolution enhances your creativity.

- If approached with humility, you begin to realise how little you know, or how things you thought you knew might have been wrong.

How to adopt a ‘granular’ approach to something you thought you knew.

As an example; never, never, never underestimate or dismiss Kihon, I say that because if you take something like the action of Junzuki, this single technique taught at the beginning of your training reveals so much more depth. Why do you think that no matter how many years you have been training you never leave Junzuki behind, you never transcend it? It’s always a work in progress.

But I guess you expected me to say that.

Another example: Take something like the role of ‘Uke’ in paired kata… it took me far too long to realise that Uke is not a mere stooge for the person performing the prescribed technique. Uke has more say in the conversational process and this ‘conversation’ continues all the way to the end of the kata.

The double-edged sword.

I left this part till the end, but it is incredibly important. Essentially, having knowledge in your head is no good on its own. For it to be given any form of concrete real-world potency, the other form of ‘knowledge’ must accompany it; that is the absorption of the technique into your body, to borrow someone else’s rather excellent description; it must be so deeply engrained that it stains your very bones!

Tim Shaw

[1] Yes, we have a syllabus book in Shikukai, and yes it has its uses as an outline, a catalogue of techniques and requirements for grading, but that’s it.

[2] I have been toying with the idea of sharing this type of material through a subscription service like Substack, but I haven’t made my mind up yet.

[3] Notice how the kata Suparinpei dropped off Otsuka Sensei’s map very early on. Also consider Otsuka’s early development of Wado and look at the list of techniques produced for the official registration in the 1930’s; it’s a kind of map, but what was its objective? Who was the map really for?

[4] ‘Dilettante’, I like this much underused word. Definition; ‘A dilettante was a mere lover of art as opposed to one who did it professionally.’

Photo credit: The Settlers screen image courtesy of: https://www.sockscap64.com/games/game/the-settlers-2/

Technical notes from the March 2022 Holland Course.

The notes are mostly intended for the students who attended the three-day weekend course but I will present them in a way that others may benefit. I will also steer clear of overly-complicated Japanese concepts that may take a whole blog post to themselves.

Underpinning Themes.

Some of the warm-up exercises were designed to encourage the students to actually map the lines of movement and tension throughout their body, this was done in a static (but dynamic) way, but also tracking these tensions and connections within movement, looking for an orchestrated and efficient whole-body movement.

I also wanted to encourage an attitude of ‘why are we doing this?’ to specific aspects of our training. This is something that Sugasawa Sensei has often spoken about, although Sensei has always stressed that an intellectual understanding alone is not enough; these things must be explored through training and sweat.

How to develop an integrated dynamic to your technique.

This was addressed initially through examining the non-blocking, non-punching hand, what I sometimes tongue in cheek call the ‘non-operative side’. Of course the pulling/retracting hand is not really exclusively about the movement of the hand/arm, it is actually working as a result of what is happening deep within your own body, it is an extended reflection of the orchestrated work of the pelvis, the spine and the deeper abdominal muscles, this combination of factors energises the limbs and the energy that originates in those areas ripples and spirals outwards to create what appears as effortless energy all firing off with the right timing – well, that’s the objective anyway.

Some movements are designed to challenge your relationship with your centre.

This was where we focussed on Pinan Sandan, which seems to pack so much in. Of course, it exists in all movement, Otsuka Sensei’s intentions for Junzuki and Gyakuzuki no Tsukomi are yet another more extreme example. As in Pinan Sandan, you can be extended and stretched to such a degree that you have to acknowledge how close you may be to losing your centre and easily destabilised.

A technical challenge!

How many different ways in Wado movement are we demanding of the various sections of our body to either move in contradictory directions, or to lock-up one section while allowing free movement in another? A clue…It’s all over the place.

Destabilising your opponent.

In this one I asked that we really try to think three-dimensionally (if not four-dimensionally, if we include a ‘time’ factor). We want to destabilise our opponent in ever more sophisticated ways – one-dimension is not enough for a finely-honed instrument such as Wado. We can tip, tilt, crush, nudge, we can even use gravity (amplified through our own body movement), we can also take energy from the floor; all of these are part of our toolkit (on the Saturday we did this through what can usefully be described as a ‘shunt’ into our partner’s weak line).

What do our ‘wider’ stances give us?

Side-facing cat stance is the widest stretched stance you will ever be asked to make (a major demand on the flexibility of the pelvis) with Shikodachi as a slightly lesser challenge, but why? What does it give us? Of course, with all of these things there are a number of actual ‘benefits’ but our focus was on the dynamics of opening the hips out to the maximum. Not in a static way; but instead as an empowered dynamic, the body operating like a spring whose tensions wind and unwind supported by the energisation of the entire body. It’s easy to see and feel when it’s not working as it should, but you just have to put the work in.

Of course, over the weekend we strayed into many other areas, but I wanted these to be our take-aways.

Tim Shaw

Martial Arts, fast burn or slow burn? – A theory.

This is something I have been thinking over for some considerable time. I believe that almost all martial arts training systems exist on a spectrum from ‘fast burn’ to ‘slow burn’.

Bear in mind that when boiled down to their absolute basic reasons for existence, all martial arts are about solving the same problem – protection/reaction against human physical aggression.

Fast Burn.

At its extreme end on the spectrum ‘fast burn’ comes out of the need for rapid effectiveness over a very short period of training time.

A good example might be the unarmed combat training at a military academy [1].

There are many advantages to the ‘fast burn’ approach. A slimmed down curriculum gives a more condensed focus on a few key techniques.

As an example of this; I once read an account of a Japanese Wado teacher who had been brought into a wartime military academy to teach karate to elite troops. Very early on he realised that it was impossible to train the troops like he’d been trained and was used to teaching, mainly because he had so little time with them before they were deployed to the battlefield or be dropped behind enemy lines. So, he trimmed his teaching down to just a handful of techniques and worked them really hard to become exceptionally good at those few things that may help them to survive a hand-to-hand encounter.

Another positive aspect of ‘fast burn’ relates to an individual’s physical peak. If you accept the idea that human physicality, (athleticism) in its rawest form rises steadily towards an apex, and then, just as steadily starts to decline, then, if the ‘fast burn’ training curriculum meshes with that rise and enhances the potential of the trainee, that has to be a good thing.

In ‘fast burn’ training, specialism can become a strength. This specialist skill-set might be in a particular zone, like ground fighting and grappling, or systems that specialise in kicking skills.

The down side.

However, over-specialisation can severely limit your ability to get yourself out of a tight spot, particularly where you have to be flexible in your options. Add to that the possibility that displaying your specialism may also reveal your weaknesses to a canny opponent.

It has to be said that a limited number of techniques whose training objectives are just based upon ‘harder’, ‘faster’, ‘stronger’ may suffer from the boredom factor, but, by definition, as ‘fast burn’ systems they may well top-out before boredom kicks in and just quit training altogether. They may well be the physical example of what the motor industry would call ‘built-in obsolescence’. [2]

Not that a martial art should be judged by its level of variety.

As a footnote; it is a known fact that in some traditional Japanese Budo systems students were charged by the number of techniques presented to them, so it was in the master’s interest to pile on a growing catalogue of techniques. I am not saying this was standard practice, but it certainly existed.

Slow Burn.

Turning my attention now to ‘slow burn’.

By definition ‘slow burn’ martial arts systems develop their efficiency over a very long time, or perhaps time as a measure is misleading? Maybe it would be better to describe the work needed to become a master of a ‘slow burn’ system as prolonged and arduous, perhaps beyond the bounds of most individuals.

For me ‘slow burn’ is defined by its complexity and sophistication and is associated with systems that have demanding levels of study, probably involving insane amounts of gruelling and boring repetitions that would test the ability (or willingness) of the average person to endure.

The positive side.

The up-side of this methodology is difficult to map as so few individuals ever get to the level of mastery and all we are left with are martial arts myths, but it would be foolish to dismiss it on these grounds alone. Most myths contain a kernel of truth and if a fraction of the myths told can be effectively proved or verified then really, there is no smoke without fire.

Looked at through the lens of modern sporting achievement, I think we can all appreciate that with the very best elite sportspeople uncanny abilities can be observed, and we know that despite the fact that many of them are blessed with unique genetic and physical disposition, an insane amount of work goes on to achieve these lofty heights (I am thinking of examples in tennis or golf, but really it applies to any top-level human endeavour – think of musicians!).

‘Slow burn’ martial arts systems may not comply with modern sports science used by elite athletes, but they were getting results any way, probably from a form of proto-sports science developed through generations of trial and error.

The ‘slow burn’ systems seem to be characterised by a reprogramming of the body in ways that require great subtlety, so subtle in fact that the practitioner struggles to comprehend the working of it even within their own bodies; it works by revelation and is holistic in nature. Mind and cognition are major components. The determination and grit that fuel the ‘fast burn’ systems are not enough to make ‘slow burn’ work, something more is needed; a reframing and reconfiguring of what we think we are doing.

Weaknesses.

The weaknesses of the ‘slow burn’ systems are pretty obvious.

Who has the time or patience to involve themselves in this level of prolonged study? It certainly doesn’t easily mesh with the demands of modern living; an awful lot of sacrifices would need to be made. It is no exaggeration to say that you would have to live your life as a kind of martial arts monk, casting aside comforts and ambitions outside of martial arts training. I often wonder how it was achieved in the historical past; I guess that beyond just living and surviving they had less distractions on their time than we do now. [3].

We know something of these systems because we can observe how, over time, the surviving examples had a tendency to morph into something altogether different; often taking on a new and reformed purpose, which of course improved their survival rate.

The examples I am thinking of have reinvented themselves as either health preserving exercise or semi-spiritual arbiters of love peace and harmony; all positive objectives in themselves and certainly not something we need less of in these current times.

I am going to duck that particular argument; it is not a rabbit hole I am keen to go down in this current discussion.

‘Slow burn’ dances with the devil when it too eagerly embraces its own mythologies; but in the absence of people who can really ‘do it’ what else have they got left? What always intrigues me is that the luminaries of the current crop of ‘slow burn’ masters are so reluctant to have their skills empirically tested. [4]

It is tempting, but it would be wrong to play these two extremes of the spectrum off against each other; I have deliberately focussed on the polar opposites, but it’s not ‘one or the other’, there are martial arts systems that are scattered along the continuum between these two extremes, and then there are others that have become lost in the weeds and suffer from a kind of identity crisis; aspiring to ‘slow burn’ mythologies while employing solely ‘fast burn’ methodologies. Can a man truly serve two masters? Or is the wisest thing to do to step back and ask some really searching questions? What is this really all about?

And Wado?

And, as this is a Wado blog, where does Wado fit in all this? I’m not so sure that the image of the line or spectrum between the two polar opposite helps us. I suppose it comes down to the vision and understanding of those who teach it – certainly there is a salutary warning illustrated by the weaknesses of both ‘Fast and Slow burn’.

Perhaps the ‘Fast Burn Slow Burn’ theory can be looked at through another lens, particularly as it relates to Wado?

For example, there is the Omote/Ura viewpoint.

To explain:

In some older forms of Japanese Budo/Bujutsu you have the ‘Omote’ aspect – ‘Omote’ suggests ‘exterior’, think of it like your shopfront. But there is also an ‘Ura’ dimension, an insider knowledge, the reverse of the shopfront, more like, ‘under the counter’, ‘what’s kept in the back room’, not for the eyes of the hoi polloi. The Ura is the refined aspect of the system.

I have heard this spoken about by certain Japanese Wado Sensei, and I have seen specific aspects of what are referred to as ‘Ura waza’, but these seem to range from the more simple hidden implications of techniques, to the seemingly rarefied, esoteric dimension; fogged by oblique references and maddening vagaries, to me they seem like pebbles dropped in a pond, hints rather than concrete actualities.

This of course begs the question; what is the real story of the current iterations of Wado as we know it? I will leave that for you to make your mind up about.

Maybe Wado is about layers?

Problems.

If we return to the original statement, “…all martial arts are about solving the same problem – protection/reaction against human physical aggression”. Ideally the success of the system should be judged by that particular measure, but clearly there is a problem with this, in that empirical data is virtually impossible to find. So how do most people create their own way of judging what is successful and efficient and what isn’t? All we are left with is opinion, which tends to be qualitative rather than quantitative. [5].

Outliers.

Let me throw this one in and risk sabotaging my own theory.

To further complicate things; a good friend of mine is a practitioner of a form of traditional Japanese Budo that that arguably and unashamedly has only one single technique in its syllabus! Yes, only one! My friend is now over 70 years old and has been practising his particular art for most of his adult life. I doubt that for one minute he would consider what he does as ‘fast burn’. I will leave you to work out what his system is, but it is no minor activity, (it is reputed to have over 500,000 practitioners worldwide!)

Tim Shaw

[1] I recently read a comment from an ex-military person who said that relying on unarmed combat in a military situation was ‘an indication that you’d f***ed up’. He said that military personnel relied on their weaponry, if you lost that you were extremely compromised. Also, he added that military personnel worked as a unit and that it is unlikely that a solo unarmed combat scenario would happen. Of course, we know that there are outliers and odd exceptions, but, as a rule… well, it’s not my opinion, it’s his.

After seeing the recent demonstration by North Korean ‘special forces’ in front of their ‘glorious leader’, basically the usual rubbish that you see from the ‘Essential Fakir Handbook’, you have to wonder who these people are kidding? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pv3L2knNodU

It’s just an opinion; not necessarily my opinion; other opinions are available.

[2] ‘Built-in Obsolescence’ Collins Dictionary definition = “the policy of deliberately limiting the life of a product in order to encourage the purchaser to replace it”.

[3] The sons and inheritors of the Tai Chi tradition of Yang Lu-ch’an (1799 – 1872) initially struggled to live up to their father’s punishing and prolonged training regime; Yang Pan-hou (1837 – 1892) tried to run away from home and his brother Yang Chien-hou (1839 – 1917) attempted suicide!

‘Tai-chi Touchstones – Yang Family Secret Transmissions’ Wile D. 1983.

[4] There was a ‘Fight Science’ documentary a few years back which looked at the claims of ‘slow burn’ martial systems and it didn’t come out well. The ‘master’ of the system was actually in very weak physical shape (largely due to smoking) although he had some well-organised physical moves and coordinated his operating system well. The truth was, he was a not the best of advocates, and for it to be truly scientific it needed many more contributors.

[5] I have another blog post planned on this theme. I fear it might ruffle a few feathers though.

The Ten Ox Herding Pictures.

If you have an interest in Zen and the martial arts, you may or may not have come across the allegory of ‘The Ten Ox Herding Pictures’.

I have been meaning to post on this subject for a while now, and although I am not really a committed Zen Buddhist adherent by any significant measure, I have an outsider’s interest.

Before I get into it in any detail, let me say that I don’t see this allegory as uniquely ‘Zen’, I think it has a wider application, particularly for anyone exploring the conundrum of self-realisation and self-actualisation.

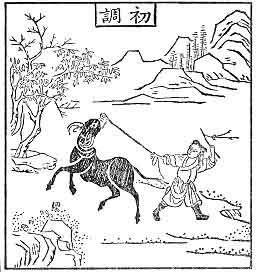

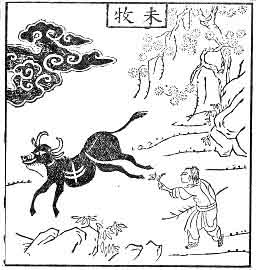

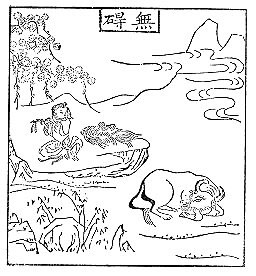

The ten images tell a story of a boy, the ox-herd, and his search for the missing ox and is a metaphor of the search for the true self (the original self); in Buddhist terms, the search for Awakening and the True Reality. The Ox-herd is the smaller self, the ego, who gradually realises that the reality is actually not far away and ultimately contained within him.

History.

Although these images developed a considerable following inside Japan, they are definitely Chinese in origin (as is Zen Buddhism actually). The earliest record of this sequence of images as a metaphor date back to the 11th or 12th century in China. There are usually accompanied by poems, but I would argue that you really don’t need them. At a visual level, you fill in the blanks with your imagination – no need for words – so very ‘Zen’.

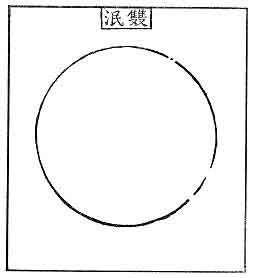

The key differences between the various versions are usually found in the last three pictures. Some versions are content to just complete the series with a blank circle, (which particularly resonates with me), but, arguably, others have a deeper story to tell, making the final picture one of a Buddha or Boddhisatva in the ‘market place’, as if to say, ‘once enlightenment is complete, return to the world, to the busiest place and just ‘be’, amongst the people’. I like that – nobody disappears up into a mountain cave; that is not the place for the sage or the enlightened one. This is a philosophy that is nearer to the Neo-Confucianists, who I believe, have a closer resonance with the martial arts that we know. [1]

A description.

A boy is out in the countryside clearly looking for something. He is sometimes shown holding a kind of tether in his fist. (The wildness of the landscape increases as the narrative develops, as if to underline the difficulty of the quest).

At first he sees the ‘traces’ of the ox (which is sometimes referred to as a bull). Whether this is tracks, or even other things bulls and oxen tend to leave behind, is not really clear.

He catches a glimpse of the untamed ox. This wild spirit shows him a ‘Way’, it’s a hint, but it gives him direction and purpose. This is the beginning of ‘Do’ or ‘Tao’.

The boy pursues the ox, taking to his task with great determination. He finally connects with the animal and manages to attach the tether to it. The hard work begins. It’s a battle between the raw energy of the ox and the willpower and determination of the boy.

The boy is unaware that he is wrestling with his own true nature and trying to bridge the gulf between his uncultured petty ego and the untainted purity of his elemental self. The Buddhists enjoy the use of metaphor to describe this pure self; they are particularly fond of the image of a lotus flower that rises in its purity from the mud of the pond, perfect and unfouled. This is the true self that resides in all of us that remains pure and clean however much with sully it our own self-inflicted contaminants; which, with discipline, can shine forth again.

This is the discipline of the Dojo and the trials of the martial way; whether you want to describe it as a form of self-transformation (internal alchemy), or the ‘forging’ process of Tanren, it is a deep emersion in the greater process of training.

The disciplining of the ox in the various versions usually seems to take a couple of pictures, as if to accentuate the battles that occur between the boy and the ox. Gradually the creature succumbs to harness and becomes placid and resigned to the process. (In some versions the ox starts out pure black in colour and by degrees changes to white).

Eventually the boy and the ox establish a harmonious union. The boy is shown riding sedately on the ox’s back, playing his flute, without a care or worry in the world. This is sometimes referred to as ‘coming home’.

In the next pictures the boy and the ox are unconcerned about each other’s presence, there is no battle any more, there is no division; they exist in the same space because there is nothing to separate them; they are one and the same; this is a state of total harmony.

The next image is often described as ‘all forgotten’. The transition is virtually complete; nothing matters. The boys is there, the ox is there, but it is as if nothing is of consequence to either of them; it is just ‘being’.

The final images plunge deeply into the unknown and the esoteric, I don’t pretend to understand them, this is ‘returning to the origin’, whether you want to call this ‘the Great Tao’ or the ‘Universal Divine’ is up to you.

As an aside; many years ago, in my college education, myself and my fellow students were introduced to a retired educationalist, I wish I could remember his name. He was a very strange individual, very calm and patient, he spoke to us as if we were his children, but not in a condescending way. Here was a man who had lived a very full life (I think he’d been in the military during WW2). He encouraged us to ask searching questions, far beyond the limited educational brief. As the discussion opened out we found ourselves questioning the meaning of existence. He talked about ‘answers’ and I asked him, ‘what happens after you find all of the ‘answers?’ He paused slightly and then said, ‘You just… disappear’.

I remember, he smiled and just left that hanging in the air. If I am reading his reply correctly, this was the final message of the ox herding pictures. Here was the blank circle, or the empty landscape.

Leonard Cohen.

This set of pictures had a further reach than most of us realised.

I don’t know how many people are aware of this but singer songwriter Leonard Cohen had a soft spot for the ox herding narrative. I think it is common knowledge that Cohen plunged deeply into the Zen lifestyle, secluding himself in monastic Zen disciplines, indulging in harsh regimes of Zazen (seated meditation).

Some of his most thoughtful and erudite poetry and lyric writing came out of that experience. What ever you think of his vocal style and singing ability there is no getting away from the fact that Cohen was a talent that maybe even eclipsed Dylan. But people seemed not to have noticed a track called ‘The Ballad of the Absent Mare’ which featured on his 1979 album, ‘Recent Songs’.

Canadian singer songwriter Jennifer Warnes recounts how Cohen came over to her house after a meditational retreat, she said, “Leonard had found some old pictures somewhere, they were called ‘The Ten Bulls’, old Japanese woodcuts symbolizing the stages of a monk’s life on the road to enlightenment. These carvings pictured a boy and a bull, the boy losing the bull, the bull hiding, the boy realizing that the bull was nearby all along. There is a struggle, and finally the boy rides the bull into his little village. ‘I thought this would make a great cowboy song,’ he joked.” [2]

Here is a sample of Cohen’s ‘cowboy song’, obviously replace ‘mare’ with ‘ox’ and it’s the same tale:

“Say a prayer for the cowboy, his mare’s run away

And he’ll walk ’til he finds her, his darling, his stray

But the river’s in flood and the roads are awash

And the bridges break up in the panic of loss

And there’s nothing to follow, there’s nowhere to go

She’s gone like the summer, gone like the snow

And the crickets are breaking his heart with their song

As the day caves in and the night is all wrong

Did he dream, was it she who went galloping past?

And bent down the fern, broke open the grass

And printed the mud with the iron and the gold

That he nailed to her feet when he was the lord

And although she goes grazing a minute away

He tracks her all night, he tracks her all day

Oh, blind to her presence, except to compare

His injury here with her punishment there…”

Conclusion.

For this story/allegory to have been around for such a long time says something about its cultural power and its spiritual value. If you take any of the great or iconic stories that have stayed with humanity all the way from antiquity to the present day, their survival is an indication of what they have to teach us, as well as their resonance with the human condition; from the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ (2100 BCE) to ‘Moby Dick’, they present models and narratives that touch and inspire us.

The ox herd pictures could be seen as a compressed version of what Joseph Campbell refers to as the ‘Hero’s journey’ [3], but Campbell’s journey has 17 stages rather than 10. Campbell’s idea is so deeply engrained into western culture that we take it for granted; examples are: Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, ‘Star Wars’, ‘The Matrix’ and even ‘Harry Potter’.

The ox herd pictures are more overtly spiritual, but given their transcendent narrative there is much there to tie in to the martial artist’s personal odyssey, after all, martial arts also aspire to a transcendence, a development of character, a personal alchemy. Let us not pretend that our martial arts journey is devoid of spirituality; by that I don’t mean the ‘Spirituality’ that is allied to organised religion; but instead, the more secular brand, associated with pondering things that are outside and beyond yourself and your whole purpose of being alive and conscious and the meaning of your existence. Buddhism sought to address these puzzles without the need to resort to Gods or supernatural deities (although certain forms of Buddhism never quite shook off the shackles of shamanism, adding things that were never part of the original message).

Of course, martial arts people tend to be very pragmatic and deep meditation on spiritual matters are not to everyone’s taste. My thinking is that while I have no desire to become a Zen Buddhist there is something to gain from exploring the wider cultural context.

But that’s my view – to you, it might just be a load of old Bull.

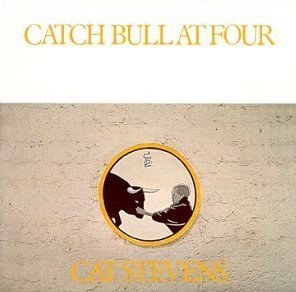

For those of you have an inclination towards trivia; Cat Stevens’ 1972 studio album ‘Catch Bull at Four’ is an obvious reference, which may well have flown right over the head of the average pop music fan of the 1970’s. The album cover makes it very clear.

Tim Shaw

[1] Through personal research and correspondence with experts in the field, I have come to the opinion that works related to the Japanese martial arts that have been pegged as coming from the Zen tradition are actually Neo-Confucian in origin, e.g. Takuan Soho ‘The Unfettered Mind’.

[2] Source: https://www.songfacts.com/facts/leonard-cohen/ballad-of-the-absent-mare

[3] See Joseph Campbell’s ‘Hero with a Thousand Faces’. 1949.

If you are interested in the crossovers between far eastern traditions and philosophy and western psychology, I found that this book has some interesting sections relating to the Ox Herding Pictures; ‘Buddhism and Jungian Psychology’, J. Marvin Spiegelman and Mokusen Miyuki, 1994.

Other references and links:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Bulls

For an excellent description of the series follow this link: https://jessicadavidson.co.uk/2015/10/02/zen-ox-herding-pictures-introduction/

For the full lyrics by Leonard Cohen’s ‘The Ballad of the Absent Mare’ follow this link: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/leonardcohen/balladoftheabsentmare.html

The image featured for ‘Catch Bull at Four’ is sourced from Wikipedia with the appropriate copyright stipulations cited here: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/3/3d/Catch_Bull_at_Four.jpg

Ox herding pictures courtesy of: https://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/mzb/oxherd.htm

Of Students and Teachers.

Luohan, courtesy of V&A.

There has been a lot of discussion about what makes a good teacher or a good Sensei; and people have found value in preparing and training the new generation of teachers/Sensei; and rightly so.

But I have a feeling that maybe we need to also look at it the other way round and perhaps teach people to be good students?

We typically think of our students as the raw material; the clay from which we mold and create; the blank slate to be written upon. Oh, we nod politely towards the idea that not all students come to us as equals; but then proceed to blithely continue on as if the opposite were true.

Can we teach people to be good students?

Well maybe…

But first we have to think that this cuts both ways. For are we not also students? Or at least we should be. We as teachers should lead by example as ‘life long learners’. As a teacher, never underestimate the student’s ability to put you under the microscope and observe how you learn and take on new material. So, while I pursue my theme, I have to cast a glance over my own shoulder.

At this point I feel I have to mention my own (additional) credentials in the area of teaching and learning, having recently retired after thirty-six years of teaching in UK secondary schools. Some of that experience boils down to very simple principles; key among these is that you are engaged with an unwritten two-way contract, or at least that’s the way it should work; the teacher gives and the student gratefully receives, in an active way (students also teach you!). Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work that way because one side of this contract sometimes welches on the deal; either actively or passively. The contract states that from the teacher’s perspective you are not doing your job if the student who walks into the room at the beginning of a lesson is the same person who walks out at the end. Something positive should have happened that results in the student growing – admittedly it might be small; it might be cumulative, but it is still growth.

Of course, this is very simplistic and there are many other factors involved. As in the Dojo, the environment has to be right to build an atmosphere conducive to development, with a positive encouragement of challenge and change; but not in a coddling bubble-wrapped way. I am reminded of commentator and thinker Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s idea of ‘Antifragile’, put briefly the concept that systems, businesses (and people) should aim towards increasing their capability to thrive by embracing stressors such as, mistakes, faults, attacks, destabilisers, noise, disruptions etc. in an active way. The antithesis of this is ‘resilience’. Resilience will protect you to some degree but it is not enough, it’s just a shell, potentially brittle, that given enough time and pressure is eventually breached.

Here is my personal take on what I think are the prerequisites of a good student:

- Empty your cup.

- Pay attention – martial artist Ellis Amdur says that progression in the martial arts is easy, all you have to do is listen. I am reminded of that very human inclination when involved in discussion; sometimes what we do when listening to someone is to fixate on one thing they have said, work out our own counter-argument in our heads while failing to listen to the rest of what they have to say. I have seen this with students in seminars, where the student asks the Sensei a question that they already know the answer to. At one level they are just looking to have their ideas endorsed, at another level they want everyone to see how clever they are – not the right place to ask a question from.

- Linked to the above; Open-mindedness. Nothing is off the table, but everything in its right place and in the right proportion.

- Understand that knowledge is a process that is ongoing; the sum of what you know is infinitely outweighed by the sum of what you don’t know. There is no end point to this.

- Self-discovery is more valuable to you than having something laid out on a plate for you. The things you achieve through your own sweat, pain and frustration you will hold as your dearest discoveries. I have seen times where a really, really valuable piece of information has been given to student and because it came so easily they dismissed it as a trifle.

- Leave your baggage behind. You may have had a lousy day at work, a fight with your partner, your kids have been ‘challenging’, but, check all of that at the door, you are bigger than the burdens you have to carry. Acknowledge that they are there but put everything in its right place. Personally, I found that troubles shrink after two hours of escape in the Dojo; distance gives you perspective.

- Avoid second-thinking the process; or, transposing your underdeveloped thinking on top of something that already exists. A blank slate is always easier to work with. I once spoke with a university Law professor who said he personally preferred the undergraduates to enter his course without having done A Level Law, he preferred the ‘blank slate’.

- Avoid making excuses in challenging situations. Nothing damages the soul more profoundly than realising that in fooling others you are often lying to yourself; it’s a stain that is really difficult to wash off. If you fail, fail heroically; fail while trying to give it your very, very best. That style of ‘failure’ has more currency than actually succeeding; not just from the perspective of others, but also from your own perspective.

- Put the time in! The magic does not only happen when Sensei is in the room. Get disciplined, get driven. Movement guru Ido Portal probably takes it to the furthest extreme by saying, ‘Upgrade your passion into an obsession’, that’s probably a bit heavy for some people, because obsessive individuals tend to be overly self-absorbed, and as such cut other people out of their lives. Whatever passion/obsession you have it is far richer when you bring other people along with you. Other people add fuel to your fire, and the other way round.

The list could go on, because teaching and learning are complex matters, much bigger than I could ever write down here. And besides… what do I know?

Tim Shaw

Can a martial art ever be taught as an algorithm?

Currently algorithms tend to be the fall-guys for all that is wrong in the world. People always leap towards the worst possible examples, like; would you every want a computer algorithm deciding who gets medical intervention, or is refused based on a calculated outcome? To some people algorithms ARE Skynet!

But, taken in the broadest definition we use some form of algorithm in many areas of life. In a nutshell it is ‘A’ leads to ‘B’, ‘B’ leads to ‘C’ or options branching off from any of the stages and it is really useful.

I ask this question in the context of martial arts because I have noticed a growth in algorithmic-style explanations of how some martial art systems work.

I can see the appeal of algorithms; they are accessible, predictable, understandable and communicable, all excellent things for a martial arts system to aspire to – the only weakness I see in terms of martial arts is that it’s really hard to make them measurable; but that’s for another discussion.

Building an algorithmic martial arts system is what you would do if you only had a very short period of time to prepare someone. A simplified system, stripped down, discarding all the inessentials (now where have we heard that before?). Four or five techniques repeated over and over until they are excellent would do the job. There are a number of obvious downsides to this; one being that its marketability is undermined by the boredom factor and the irony is that the ‘stripped down’ system has to build in greater complexity to make it interesting (more funky takedowns, armbars, gooseneck wrist locks etc.), and it turns into the one thing it was trying hard not to be.

In a way this follows on from a previous blogpost I had written; ‘Is your martial art complicated or complex?’

There are alternative approaches, but it depends on what your aspirations are – in fact it depends on a whole raft of things, including, how much time do you have available to invest in this? Where do your priorities lie in terms of what you want out of your martial art training? What system suits you both physically and mentally? (No, they are not all the same).

Something that is close to an algorithmic approach might be akin to taking a course in CPR or First Aid. In that instance you might be motivated by the worry of how you might be able to cope if you were unfortunate to arrive on the scene of an accident; would you be able to do the right thing? Lives might be at risk.

But let’s say you really wanted to dig deeper into this area, really wanted to become actively and positively involved in the saving of lives and human physical welfare. Surely then, if you had the opportunity and the inclination to do so you would study medicine? To do so would be to plunge deeply into what lies beneath the skin; even to looking at what operates at cellular level, with all the hours of dedication and years’ work that this involves. And for that to happen (as with all complexities) you have to go backwards before you go forwards, you have to turn over everything you thought you knew. In reality, this is a description of martial arts as a ‘Way’, a non-algorithmic ‘complex’ system; this is Budo.

Why would you want to put yourself through the long painful slog of a Budo system, one that is so arduous that you feel you are moving backwards instead of forwards, one where you are actually significantly weaker, structurally confused, coordinationally muddled and intellectually perplexed; in other words, not all that dissimilar to a first year medical student. Why would you do it?

To be clear; martial arts and everything associated with it is a physical conundrum that is engaged in by humans, not robots; fighting is not mechanistic, it is organic, it is a ‘complex system’. It is like swimming in the ocean, it’s not a two metre paddling pool.

A question that is often asked; just how do you engage with martial arts as a complexity; how does it actually work? I will have to be honest here; to answer that question I feel I really don’t have the qualifications, but I might offer some pointers. There are definitely guiding concepts that act like a map to keep you on the right road. But make no bones about it; knowing the concepts only in your head is about as useful as land swimming; this has to be done by the body and in as live a situation as is possible, while still remaining within civilised constraints of course.

To explain further:

The ‘complex’ martial art system differs from the algorithmic approach the same way that the chess computer AlphaZero was from its nearest rival Stockfish 8. For Stockfish all possible chess combinations were programmed in manually, while AlphaZero only learned the rules of chess (it took a mere 4 hours), AlphaZero then played itself through a phenomenal number of games to build up its stock of possibilities. It subsequently played a challenge match against Stockfish 8 and in a 100 games it never lost a single one. AI people say this is how human intelligence works. I would argue that this is how the ‘complex’ martial artist works. In algorithmic martial arts it’s pretty clear that you have to slip between modes, a bit like changing gear, but with a ‘complex’ Budo martial arts you are always in gear, because it’s built around a fundamental integral core of Principles, this is the nucleus of what you do, everything spirals out from that point; anything else is just nuts and bolts; even the funky takedowns, the armbars and the gooseneck locks.

The bad news is that you don’t read this stuff in a book, you don’t see it on YouTube and, unless you’ve got the eyes to REALLY see what’s going on, you certainly won’t find it in a one-off seminar.

Tim Shaw

Postscript: As an afterthought, Budo, like Medicine is not solely about the visceral stuff, both disciplines are underpinned by ethical, philosophical and moral considerations (in medicine it is reflected in the Hippocratic Oath).

The two wheels of a cart.

I had heard a while ago that theory and practice in martial arts were like the two wheels of a cart. One without the other just has you turning around in circles.

It is a convenient metaphor which is designed to make you think about the importance of balance and the integration of mind and body. On one hand, too much theory and it all becomes cerebral, and, on the other hand practice without any theoretical back-up has no depth and would fall apart under pressure.

But here’s another take on it, from the world of Yoga.

Supposing the ratio of theory to practice is not 50/50, and it should be more like 1% theory and 99% practice?

So, for some of the yoga people it’s is very nearly all about doing and not spending so much time thinking about it. I sympathise with this idea, but I feel uneasy about the shrinking of the importance of theory and understanding about what you are doing.

I am sure that I have mentioned in a previous blog post about how the separation of Mind and Body tends to be a very western thing. In eastern thinking the body has an intelligence of its own, over-intellectualisation can be a kind of illness. How many times have we been told, “You’re overthinking it, just do it”? Or, “Don’t think, feel”.

Maybe this points to another way of looking at the diagram above…

Perhaps it’s more like this?

I.e. a huge slice of theory, study, reflection, meditation, intellectual exploration and discussion (still making up only 1%), and an insane amount of physical practice to make up the other 99% to top it off!

Just a thought.

Tim Shaw

Know the depths of your own ignorance.

In Ushiro Kenji’s book, ‘Karate and Ki – The Origin of Ki – The Depth of Thought’, he mentions that when your sensei asks you if you understand, you should always be wary of answering it with an emphatic “Yes”. A better answer may be, “Yes, but only to my current level of understanding”. How can you really state that you are fully in the picture of what your Sensei is trying to communicate? It all becomes relative to your current point of development, and (if we are being realistic) we are all existing on a continuum of expanding knowledge – or we should be.

This is nothing new. Socrates (469 – 399 BCE) had worked it out (and was despised by some of his contemporaries for this). Here is a quote from the Encyclopaedia of Philosophy [online], “[The] awareness of one’s own absence of knowledge is what is known as Socratic ignorance, … Socratic ignorance is sometimes called simple ignorance, to be distinguished from the double ignorance of the citizens with whom Socrates spoke. Simple ignorance is being aware of one’s own ignorance, whereas double ignorance is not being aware of one’s ignorance while thinking that one knows.”

In my last job I spent many years advising teenagers about to depart for university, and one thing I used to say to them was that one of the worst insults that could ever be thrown at them was for someone to describe them as ‘ignorant’; I also included shallow as well, but ignorance was the most heinous of crimes.

An obvious part of this is to be aware of the lenses you are looking through (check out, ‘observer bias’ and the closely related ‘cognitive dissonance’). Martial artists seem particularly prone to this. We see this when someone has a pet theory, or a favourite concept and feels a need to carve it in stone. Once it’s gone that far down the line there’s really no going back, and even in the light of new evidence which contradicts or turns over the pet theory they are stuck with it and it can become a millstone around their neck.

The error is in not acknowledging your own ignorance; feeling you should set yourself up as the authority in all things.

We are not very good at understanding the limits of our own knowledge. We make an assumption that in all areas of life we are existing on the cutting edge of what is possible – that may be true but we still encounter stuff that is either imperfect, or goes wrong, or breaks down; be that in systems, societies or technology. Deep down we know there is the possibility of improvement and advancement, but that’s always for tomorrow.

Take medical science as an example. Someone recently said to me that there’s never been a better time to be ill. Now, I take issue with that in more than one way; the obvious one being that really there is no ‘better’ time to be ill at all! Another point is that this comment was probably the same one used by an 18th century surgeon when he was just about to saw someone’s leg off without anaesthetic.

I suppose it is the arrogance within humanity that arrives at these rather bizarre conclusions. Perhaps in a way it is a kind of comfort blanket; maybe we are hiding from a much more sobering reality? Sometime in the future will some social historians be looking back at us and marvelling at how primitive and naïve we were? Or perhaps this is already happening within our own lifetime? Maybe my generation has been the first to witness such a dramatic rate of change and advancement. It’s a fact; compared to previous centuries the rate of change has speeded up phenomenally. One factor alone sums it up nicely – the Internet. I think we can talk confidently about ‘Pre-Internet’ and ‘Post-Internet’.

However, human skill development at a physical level does not increase at the same high speed that technological development can. Athletes can still shave a hundredth of a second off a 100 metre sprint, but it can take years to achieve this comparatively tiny gain. In fact any significant human skill still takes hours of dedicated practice to achieve. A 21st century aspiring pianist still has to put the same amount of hours in that an 18th century one did. Of course we are smarter about how we organise the learning process, this is sometimes supported by technology but the body still has to do the work. Our attitude towards human physical achievement and ambition has changed over the last 100 years. Take the example of Roger Bannister’s breaking of the 4 minute mile; critics at the time claimed that Bannister had cheated because he trained for the event! Their attitude of course was that Bannister should have done it based upon his own innate undeveloped physical attributes; his God given talent.

The acknowledgment of ignorance is inevitably a positive thing; it’s the acceptance that there is a whole big world out there, a boundless uncharted territory which is loaded with amazing possibilities.

Tim Shaw

Craft and Craftsmanship.

It goes without saying Martial Arts can easily be categorised as a human skill (a Craft). It’s a trained activity directed at solving specific problems. Problem solving can be achieved to different levels depending on the competence of the person addressing the problem. It could even be argued that problem solving is binary – either you solve the problem or you don’t. But problem solving is not necessarily an ‘end-stop’ activity, there’s more to this than meets the eye.

Following this ideas that martial arts art are crafts, I would like to explore this further to see if anything can be gained by shifting our perspective and pushing the boundaries and looking at what a ‘craft’ actually is.

Sociologist Richard Sennett has a specific interest in Craft and Craftsmanship. For him ‘Craft’ is just doing the job, probably the same as everyone else, just to get it out of the way; a basic necessity. But ‘Craftsmanship’ is the task done in an expert, masterly fashion (Like the famous story of the master butcher in The Chuang Tzu). But the craftsman’s response to the problems/challenges he faces is not just a mechanical one; it changes according to the situation, and, whether it is master butcher, musician, painter or martial artist, the challenge is fluid, and as such adjustments are made on the spot and new ways of doing the same thing evolve. The craftsman doesn’t ‘master’ his art, because his mastery is ever-moving….or it should be. The skills of the master craftsman becomes a linear on-going project, not an end-stop.

Sennett says that craftsmanship at a basic level involves identifying a problem, then solving that problem; but that it shouldn’t end there. The solving of an individual problem often leads on to new problems that the craftsman may not have known existed prior to engaging with that particular individual problem. A combination of his intellect, his curiosity and his evolving level of mastery leads him towards tackling that next unforeseen problem and the process goes on.

In his research Sennett interviewed ex-Microsoft engineers who lamented the closed system of Microsoft, but lauded the open creative possibilities of Linux – for him this was an example of craftsmanship in progress. I am reminded of the comparison between the old style chess programs and the latest AlphaZero chess program. With the old style programs the moves had to be inputted by human hand; with AlphaZero the only input was the rules of the game; the computer then was free to play millions of games against itself to work out an amazing number of possibilities that just multiplied and multiplied.

It is not a huge leap to apply this way of thinking to Wado. Utilising the skills we develop in a free-flowing scenario engages with many problem solving opportunities that unfold in rapid succession. If we do it well it is all over very quickly, or, if we are working against a very skilled opponent the engagements may be more complicated, for example using an interplay of creating or seizing initiatives (‘Sen’). But to do this your toolkit (your core principles) must have a solid grounding otherwise you might have the ideas in your head but not necessarily the trained physicality to carry them out, and certainly not in the split second often needed.

If we really want to develop our craftsmanship we have to look for the opportunities that are created beyond the basic level of simple problem solving, but without losing the immediacy and economy that underpins Wado. I know that sounds like a contradiction but it is possible to be complex in your simplicity; it’s just a matter of perspective.

Tim Shaw

Flow

My intentions are to present a book review and at the same time expand it to look at the potential implications for martial artists of this very interesting theme.

For anyone who has not discovered the ideas of psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi get hold of his book. ‘Flow – The Psychology of Happiness’.

This came to me from a very roundabout route. Initially I was curious about Mushin no Waza, (technique of no-mind), a concept many Japanese martial artists are familiar with; but further research lead me on to ‘Flow States’. Musicians might describe this as working ‘in the groove’, or ‘being in the pocket’, psychologist Abraham Maslow called it ‘Peak Experience’, being so fully immersed in what you do, in a state of energised focus almost a reverie. It’s all over the place with sporting activities. Csikszentmihalyi describes it as an ‘optimum experience’.

I should say at this point that it’s nothing mystical or magical, although some would like to describe it as such. As with magic – magic ceases to become magic once it’s explained. I know that once the illusionist’s sleight of hand technique is revealed we all feel a little disappointed and the magical bubble has burst, but if explanation leads to greater understanding it’s a loss worth taking. So it is with Csikszentmihalyi’s book; he unpacks the idea and neatly describes the quality of flow experiences as well explaining the cultural and psychological benefits.

In a nutshell, flow states happen when:

Whatever activity you are engaging in creates a state of total immersion that you almost lose yourself within the activity.

The identifying qualities include:

- Total focus (excluding all external thoughts and distractions).

- The sense of ‘self’ disappears but returns renewed and invigorated once the activity has concluded.

- Time has altered, or becomes irrelevant.

- The activities must have clear goals.

- A sense of control.

- Some immediate feedback.

- Not be too easy, and certainly must not be too hard and entirely out of reach.

Now, I challenge you to look at the above criteria and ask yourself how these line up with what we do in the Dojo. I would bet that some of your most valuable training moments chime with the concepts of the flow state – you have been there. Many of us struggle to rationalise it or find the vocabulary to explain it, but we know that afterwards we have grown.

This ‘growth’ is vital for our development as martial artists and human beings. This is what they mean when they describe martial arts as a spiritual activity; but ‘spiritual’ devoid of religious baggage, but ironically in traditional martial arts there is generally a ritualistic element that sets the scene and promotes the mind-set necessary to enable these flow state opportunities; so I wouldn’t be too quick to dismiss this side of what we do.

Csikszentmihalyi says that flow experiences promote further flow experiences; i.e. once you have had a taste of it you yearn for more, not in a selfish or indulgent way but instead part of you recognises a pathway to human growth and ‘becoming’. We become richer as these unthought-of experiences evolve; we become more complex as human beings.

What is really interesting is that flow states are not judged upon their end results; for example the mountaineer may be motivated by the challenge of reaching the top of the rock face but it is the act of climbing that creates the opportunity and pleasure and puts him in the state of flow and rewards him with the optimal experience that enables him to grow as a human being. So, not all of these experiences are going to be devoid of risk, or even pain and hardship, they may well be part of the package.

Another aspect is that in the middle of these flow experiences there is no space for errant thoughts, if you are doing it right you will have no psychic energy left over to allow your mind to wander. In high level karate competition the competitor who is ‘in the zone’ has no care about what the audience or anyone else might think about his performance or ability; even the referee becomes a distant voice, he is thoroughly engaged in a very fluid scenario.

How many times have you been in the Dojo and found that there is no space in your head for worries about, work, home, money, relationships. You could tell yourself that this ‘pastime’ just gives you an opportunity to run away and bury your head in the sand, but maybe it’s more a case of creating distance to allow fresh perspective.

If Otsuka Sensei saw Budo as a truly global thing, as a vehicle for peace and harmony, then consider this quote from author and philosopher Howard Thurman, and apply it to the idea of Flow;

“Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

Tim Shaw

Sanitisation.

Early 20c Japanese Jujutsu.

I recently watched a YouTube video which was focussed upon the sanitisation of old style Jujutsu techniques that were cleaned up to make them safe for competitive Judo. Throws and techniques which were originally designed to break limbs and annihilate the attacker in dramatic and brutal ways were changed to enable freeform Judo randori where protagonists could bounce back and keep the flow going.

This inspired me to review techniques in Wado, some of which I believe went through a similar process.