Technical

Humbled Daily.

Before I launch into this latest blog theme, just a quick word about a new development.

I wanted to extend this writing project into something bigger and so have set up on Substack, a subscription service which is really taking off. I will write a following blog post to outline my plans, but basically it is already up and running. Please support this new project. It can be found at: https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

On with the theme…

In a recent interview with movement guru Ido Portal he mentioned that grapplers and wrestlers get humbled daily, and it was a healthy thing. They roll on the mat with people of different abilities and frequently experience the challenges that such opportunities present. Often, they fail in their intentions; frequently someone else’s intentions win over theirs and they experience failure. In fact, an intense session may well involve a rolling series of mini-victories and mini-defeats. These are all valuable growth experiences. [1]

Portal says that this seldom happens in traditional martial arts, and he’s right. While not being entirely absent, it certainly doesn’t happen to that intensity.

In traditional martial arts very often the training scenario is so tightly directed that there is little space for this type of training; or, in some cases ‘loss’ is too high a price to pay that it is actually demonised, or only seen for its negative attributes.

What are the real obstacles for us as traditional martial artists to engage in parallel ‘humbling’ interchanges? Here is a list of the potential problems:

- Attitude, this might be related to ego, rank, status etc. I find it ironic that ‘humility’ in Budo is seen as a positive attribute, yet the aforementioned attitude problems are allowed space in the Dojo.

- Avoidance. We know the phrase ‘risk averse’, if you don’t willingly embrace challenge it’s going to be very difficult to improve. [2]

- The constrictions of the training format. We know that our training in traditional martial arts is limited by having to fit so much into a limited time; our priority has to be the syllabus as this is the framework upon which everything depends. How to overcome these limitations often falls on the creativity of the Sensei. Some are good at this, others not so.

- The absence of ‘Play’. Often derided, but, if we think about it, some of our most powerful learning experiences have come to us through play – we only have to think of the physical challenges of our childhood.

And what about competition and sport?

The demonisation of ‘loss’ is perhaps amplified when martial arts become sports. Although, today there is a trend where everybody has to be a winner, it’s an illogical formula. I will counter this with the pro-hierarchy viewpoint. If there is no ladder-like hierarchy to climb then there is no value system. When everything becomes the same worth there’s nothing to aspire to, no striving, no reaching, the whole enterprise becomes meaningless.

In a karate competition the winner’s position becomes of value because of everyone who pitched in and competed on that day. The winner should feel genuine gratitude towards all of those who competed against him or her, it was their efforts that elevated the champion to that top position. And, although all of those people don’t get the trophy or the accolades, they gain so much in the experience of just competing. This is the true ‘everybody is a winner’ approach.

In a healthy Dojo environment instructors are beholden to devise ever more creative ways of training to allow students to experience lots of free-flowing exchanges, where mistakes are seen as learning experiences. A while back, I shamelessly stole a phrase from an ex-training buddy who was from another system. He called this stuff ‘flight time’, as in, how trainee pilots clock up their hours of developing experience. If you get the balance right nothing is wasted in well designed ‘flight time’ in the Dojo. Over the last ten years or so I have been working on different methods of creating condensed ‘flight time’ experiences. When it’s going well there are continually unfolding successes and failures, and the best part of it is that during training everybody gets it wrong sometimes and therefore has to learn to savour the taste of Humble Pie.

Bon Appetit.

Tim Shaw

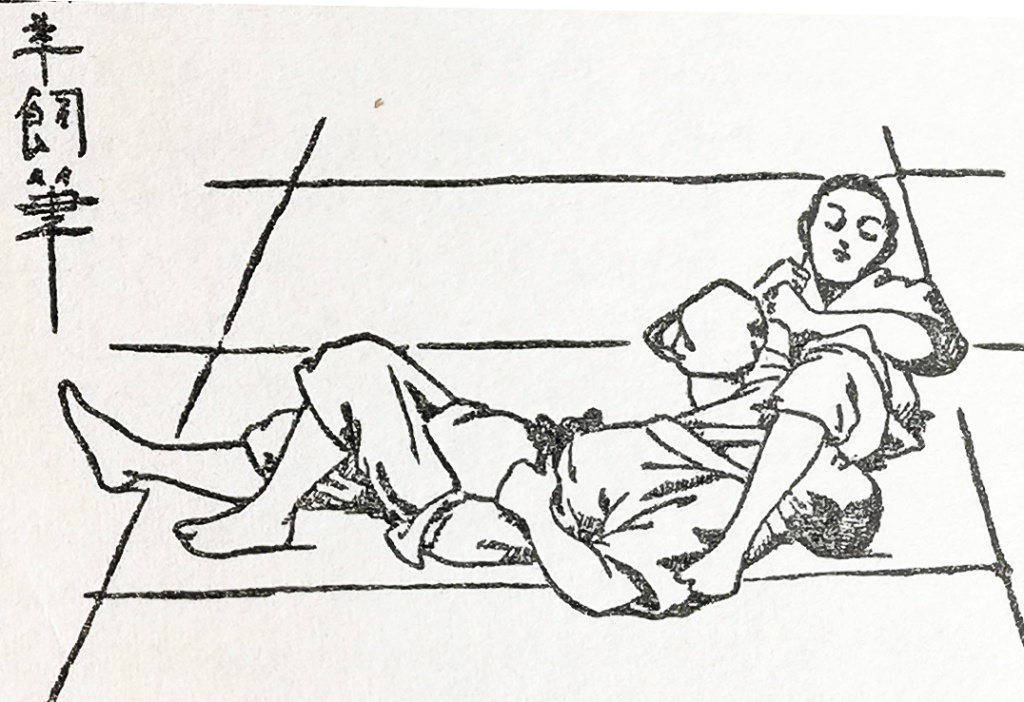

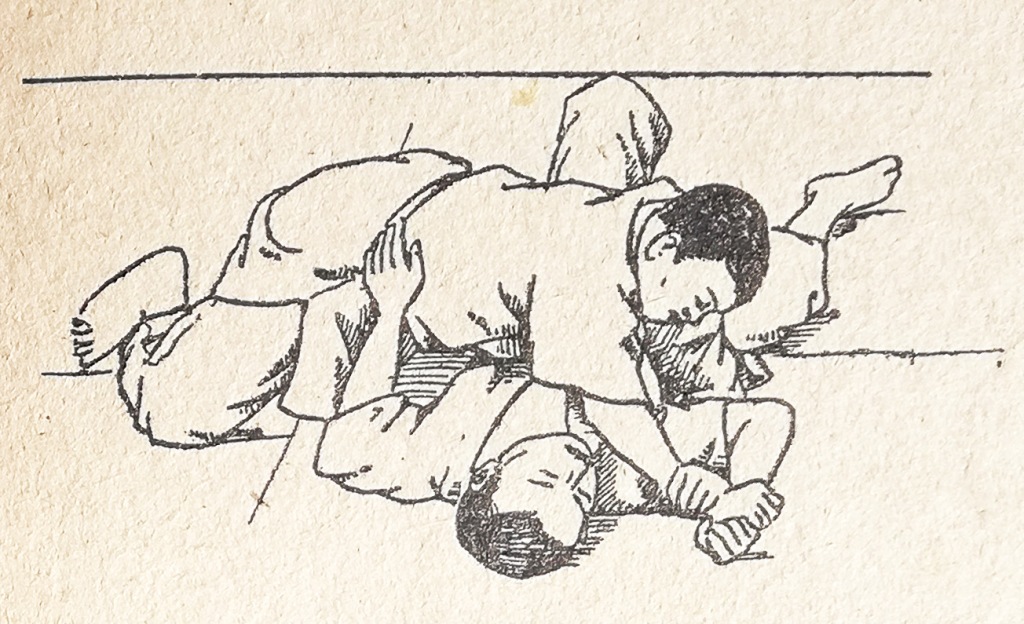

[1] I have heard similar things from the early days of Kodokan Judo, hours and hours of rolling and scrambling with opponent after opponent.

[2] ‘Invest in loss’ is a phrase often heard among Tai Chi people. It describes the lessons learned from failure. The late Reg Kear told a story about his experiences with the first grandmaster of Wado Ryu, who said something similar to, ‘when thrown to the floor, pick up change’ and then, with a smile, mimed biting into a coin.

Featured images from ‘The Manual of Judo’, E. J. Harrison 1952.

Technical notes from the March 2022 Holland Course.

The notes are mostly intended for the students who attended the three-day weekend course but I will present them in a way that others may benefit. I will also steer clear of overly-complicated Japanese concepts that may take a whole blog post to themselves.

Underpinning Themes.

Some of the warm-up exercises were designed to encourage the students to actually map the lines of movement and tension throughout their body, this was done in a static (but dynamic) way, but also tracking these tensions and connections within movement, looking for an orchestrated and efficient whole-body movement.

I also wanted to encourage an attitude of ‘why are we doing this?’ to specific aspects of our training. This is something that Sugasawa Sensei has often spoken about, although Sensei has always stressed that an intellectual understanding alone is not enough; these things must be explored through training and sweat.

How to develop an integrated dynamic to your technique.

This was addressed initially through examining the non-blocking, non-punching hand, what I sometimes tongue in cheek call the ‘non-operative side’. Of course the pulling/retracting hand is not really exclusively about the movement of the hand/arm, it is actually working as a result of what is happening deep within your own body, it is an extended reflection of the orchestrated work of the pelvis, the spine and the deeper abdominal muscles, this combination of factors energises the limbs and the energy that originates in those areas ripples and spirals outwards to create what appears as effortless energy all firing off with the right timing – well, that’s the objective anyway.

Some movements are designed to challenge your relationship with your centre.

This was where we focussed on Pinan Sandan, which seems to pack so much in. Of course, it exists in all movement, Otsuka Sensei’s intentions for Junzuki and Gyakuzuki no Tsukomi are yet another more extreme example. As in Pinan Sandan, you can be extended and stretched to such a degree that you have to acknowledge how close you may be to losing your centre and easily destabilised.

A technical challenge!

How many different ways in Wado movement are we demanding of the various sections of our body to either move in contradictory directions, or to lock-up one section while allowing free movement in another? A clue…It’s all over the place.

Destabilising your opponent.

In this one I asked that we really try to think three-dimensionally (if not four-dimensionally, if we include a ‘time’ factor). We want to destabilise our opponent in ever more sophisticated ways – one-dimension is not enough for a finely-honed instrument such as Wado. We can tip, tilt, crush, nudge, we can even use gravity (amplified through our own body movement), we can also take energy from the floor; all of these are part of our toolkit (on the Saturday we did this through what can usefully be described as a ‘shunt’ into our partner’s weak line).

What do our ‘wider’ stances give us?

Side-facing cat stance is the widest stretched stance you will ever be asked to make (a major demand on the flexibility of the pelvis) with Shikodachi as a slightly lesser challenge, but why? What does it give us? Of course, with all of these things there are a number of actual ‘benefits’ but our focus was on the dynamics of opening the hips out to the maximum. Not in a static way; but instead as an empowered dynamic, the body operating like a spring whose tensions wind and unwind supported by the energisation of the entire body. It’s easy to see and feel when it’s not working as it should, but you just have to put the work in.

Of course, over the weekend we strayed into many other areas, but I wanted these to be our take-aways.

Tim Shaw

You’d better hope you never have to use it – Part 2.

“Smash the elbow”, “tear the throat out”, “snap the arm like a twig”, “gouge the eyes with your thumbs”. I have heard these things said by martial artists during classes. But I find myself asking, how do you know? and have you ever done that? Have you ever used your thumbs to gouge out somebody’s eyeballs? And on top of that, how do you know you won’t freeze like a rabbit in the headlights? Or, how do you know if you have enough resilience (or lived experience) to be able to suffer a terrible beating before you get a chance to put in that one decisive game-changing shot?

Empirical evidence versus anecdotes.

Effectiveness, can you prove it? Can it be quantified in a scientific way? Is the data available?

Every martial artist probably has a dozen stories as to why their martial arts method is effective as a fighting system and none of these incidents ever happen inside the Dojo – how could they, it’s supposed to be a safe training environment?

I have my own ‘go-to’ anecdotes, but equally I have another set of anecdotes where martial arts practitioners have come unstuck – but nobody talks about those, least of all the people who it has happened to (understandably). [1].

Anecdotes may be fun to recount but all they do is muddy the water, they are too random to qualify as evidence. And, if you look at some of these stories in the cold light of day you often have to wonder about (a) their veracity, (b) which way the odds were stacked, (c) whether elements of luck or chance were involved; but one thing is clear, they cannot really be used as definitive proof that your system works, after all, the system is the system and You are not the system.

The anecdotes may suggest that in certain circumstances your chances of coming out on top in a violent attack might be slightly higher – but they could also suggest that you might come out worse (probably because of over-confidence, or an unrealistic evaluation of your own ability).

The problem with fantasy.

Now compare that to movie fantasies of physical confrontations. I cite two examples that come to mind.

The first being Tom Cruise as Jack Reacher, where Reacher takes a bunch of guys on after they offer him out from a bar ( link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hu1MtT_S3bc

The thing is, deep down, we all want it to be like that.

And then Robert Downey Jnr as Sherlock Holmes in a bare knuckles contest (link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-z5139CW1I

This last one is about as extreme an example as is needed to make my point that fantasy is fantasy. (To paraphrase Mike Tyson, ‘Everybody has a plan until they get a punch in the mouth’.)

The Sherlock Holmes example is akin to treating violence like a chess game – if I plan and think several moves ahead then my plan will bring about the downfall of my opponent…. wrong. When it gets to the ‘trading punches’ stage you have already entered the world of chaos, thus ramping up the unpredictability exponentially.

It is potentially fatal to confuse Complex with Complicated [2] and the zone of chaos is indeed Complex. This is why those who are supremely skilful at navigating the Complex world have to do it without thought, artifice or calculation, they are like expert nautical mariners in a tossing sea, who work on instinct, they have an overarching understanding of Principle, their skills are not a bunch of cobbled together tricks that they have memorised hoping for that moment to happen.

I know that there are critics of the Principle angle in martial arts (particularly Wado), usually they fail to understand it and ask, what is this ‘Principle’ thing anyway? I am tempted to reply with something like the Louis Armstrong quote about the definition of jazz, “Man, if you have to ask what jazz is – you’ll never know”. (See my blog post on ‘Fast Burn, Slow Burn Martial Arts’ for a clue as to how it works). These same people remind me of the ‘Fox with no tail’ a moral story from Aesop].

When people talk about ‘functionality’, ‘functional combative skills’, this has to be about effectiveness, surely? But You can’t talk about that without some form of measure, if there is no measure then it’s all opinion and as such, we can take it or leave it. The person who makes the statement can only hope that we trust their opinion as an ‘expert’, but again, an expert based on what experience; their ability (as proven) to ‘snap someone’s arm like a twig, or gouge their eyes out’? I realise that there are people out in the martial arts world whose whole authority rests on this issue and it’s not my place to call them out, particularly as I also have no experience of ‘snapping arms’ to support any claims I make, but just apply a little logic to it.

Of course, I reckon that if I take my opponent’s elbow over my shoulder and exert a forceful two-handed yank downwards I might be able to ‘snap his elbow like a twig’, but I doubt he’s going to let that happen without a hell of a struggle (unless I am Sherlock Holmes of course). Meanwhile, he has barrelled into me, knocked me on my back and is sat on my chest raining punches into my face, and then his mates join in to kick me in the head for good measure – elementary my dear Watson.

Looking for evidence in history.

I feel I have to address this one. Anyone who looks for evidence in history is on to a sticky wicket. History is notoriously unreliable. We know this because current historical revisionist methods are revealing that many things we thought were true may not be so. For example; everyone knows that it is the victors who write the history.

If we take our history inside Japan and Okinawa and we listen to serious, open-minded researchers, we find that some of the things we took for granted may well not be true.

To give a few examples:

- Zen Buddhism does not have the monopoly in Japanese martial arts, certainly karate is not ‘Moving Zen’.

- The 19th century Samurai were not the apex of Japanese martial valour and skill. Set that two or three hundred years earlier and you might be about right.

- Okinawan martial arts were not the result of a suppression imposed by Japanese Samurai; it was not that simple. Okinawan people were generally peaceful and society was well-structured, it certainly was not the Dodge City that some people like to suggest, it seems that the martial arts of Okinawa reflected this, an extreme martial arts crucible it certainly wasn’t, certainly if you compare it with what was happening in Japan between 1467 and 1615. I don’t point that out to discredit the Okinawan systems, it’s just an observation and there were exceptions, e.g. Motobu Choki, who certainly had his ‘Dodge City’ moments.

As time moves forward all we are left with is the mythologies, hardly something to judge the functional abilities of teachers who are long dead, so all we have available is guesswork, assumptions and opinions; not really scientific or objective. So, anyone who wants to hang their ideas on that particular hook would be wise to keep an open mind.

How would martial arts work in a defence situation? A proposition.

To answer this, I would speculate that there are several high-level outcomes that are possible, and none of them look anything like either the movie fantasy image, or the types of techniques that are, ‘a bunch of cobbled together tricks that have been memorised hoping for that moment to happen’ [3].

- The highest level has to be that nothing happens, because nothing needs to happen. The world calms down and order rules the day; chaos is banished.

- The next highest level is probably where the aggressor just seems to fall down on his own. Here are my two nearest assumptions on this (one anecdotal and the other historical – but after all, I have to pluck my examples from somewhere). The first is a story about Otsuka Sensei dealing with a man who tried to mug him for his wallet in a train station. Otsuka just dealt with the guy in the blink of an eye and when asked what he did, he replied, “I don’t know”. The other is the historical encounter between Kito-Ryu Jujutsu master Kato Ukei and a Sumo wrestler who twice decided to test the master’s Kato’s ability with surprise attacks, and both times seemed to just stumble and hit the dirt [4].

- Anything below those two levels would probably involve one single clean technique, nothing prolonged, maybe appearing as nothing more than a muscle spasm, nothing ‘John Wick’, certainly nothing spectacular – job done.

- Then you might plunge down the evolutionary scale and have two guys smashing each other in the face to see who gives up first.

Conclusions:

The original objectives of these two blog posts were to challenge the assumptions we seem have made about the nature of self-defence (in its broadest interpretation) and to put forward some different angles, explode a few myths and to present the idea that all that glitters is not gold.

I don’t have the answers, but then it seems, neither does anyone else. But we shouldn’t just throw our hands up in the air. Keep on with the focus on defending ourselves and refining our technique and by all means teach self-defence as a supporting disciple or on dedicated courses, it is a brilliant way for martial arts instructors to engage with the community in a positive and confidence building way; however, keep it realistic and not just fearful.

For those who claim that their approach has more ‘functionality’ I would humbly suggest that that you might want to look towards the key questions; objectively, how can you prove that? Maybe what you are asking for is a leap of faith? My view is that the data is not there and that it is just lazy logic. [5]

There are people who want to claim their authority from the ‘short game’, while I would suggest that there is another game in town; the ‘long game’. Targets really need to be aspirational and ambitious, not ducking towards the lowest common denominator, i.e. the ‘fear factor’ of the anxious urbanite. Your authority is not derived from your ability to ring the metropolitan angst bell; or to yank the chain of the frustrated metrosexual male who feels he is cut adrift and fretful about his role in contemporary society and lost in a maelstrom of surging confusion.

The bottom line is; get real and dare to think differently.

As a last word, these posts are not meant to be definitive, or to cover all aspects of self-protection. I could have included comments about how the law views self-defence, or how much mental attitude is a part of self-defence, or adrenalin, fight and flight etc, without even mentioning the number of young men in the UK who die through stab injuries. But maybe another day.

Tim Shaw

[1] One event happened fairly recently where I had bumped into a martial artist from another system, an acquaintance, in a nightclub. He’d had a drink or two and proceeded to bend my ear about how ‘the trouble with most martial artists is they have never been in a real fight, never trained for it, etc.’ And, as if the God of Irony was looking down upon him; within seconds of him waving me goodbye, he crossed paths with the wrong person and ended up as a victim, laid out and bleeding. I guess he didn’t get the chance to ‘snap the arm like a twig’.

Be careful what you wish for.

[2] See my blog post on Systems. https://wadoryu.org.uk/2020/01/29/is-your-martial-art-complicated-or-complex/

[3] These methods often assume that the opponent is going to present themselves like a bag of sand and allow you to engage in an ever-complex string of funky locks, take-downs, arm-bars etc. etc. Sherlock Holmes would definitely approve.

[4] Source: ‘Famous Budoka of Japan: Mujushin Kenjutsu and Kito-ryu’. Kono, Yoshinori, Aikido Journal 111 (1997). According to Ellis Amdur in his book ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’ this is pure Principle and Movement in practice (my paraphrase).

[5] Similar to the way people talk out about ‘life after death’, i.e. how do you know? Conveniently, nobody has ever come back to tell us. Ergo; you never have to validate your claims.

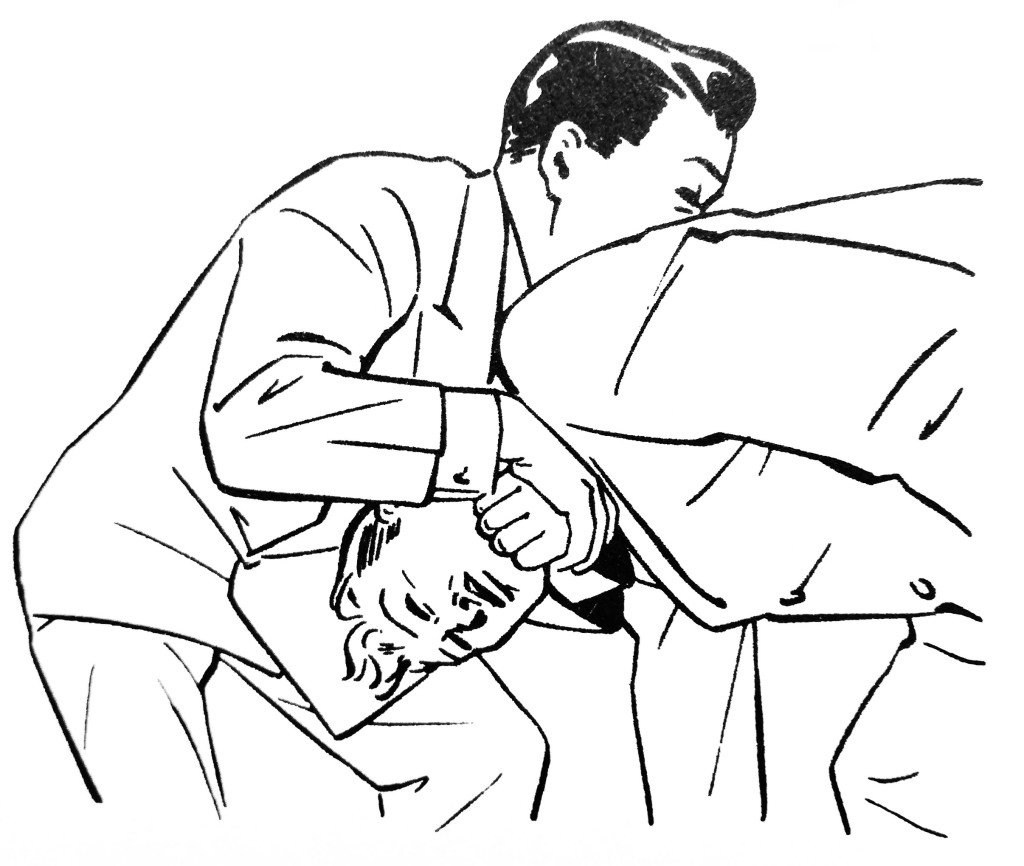

Image credit: Kiyose Nakae ‘Jiu Jitsu Complete’ 1958.

Martial Arts, fast burn or slow burn? – A theory.

This is something I have been thinking over for some considerable time. I believe that almost all martial arts training systems exist on a spectrum from ‘fast burn’ to ‘slow burn’.

Bear in mind that when boiled down to their absolute basic reasons for existence, all martial arts are about solving the same problem – protection/reaction against human physical aggression.

Fast Burn.

At its extreme end on the spectrum ‘fast burn’ comes out of the need for rapid effectiveness over a very short period of training time.

A good example might be the unarmed combat training at a military academy [1].

There are many advantages to the ‘fast burn’ approach. A slimmed down curriculum gives a more condensed focus on a few key techniques.

As an example of this; I once read an account of a Japanese Wado teacher who had been brought into a wartime military academy to teach karate to elite troops. Very early on he realised that it was impossible to train the troops like he’d been trained and was used to teaching, mainly because he had so little time with them before they were deployed to the battlefield or be dropped behind enemy lines. So, he trimmed his teaching down to just a handful of techniques and worked them really hard to become exceptionally good at those few things that may help them to survive a hand-to-hand encounter.

Another positive aspect of ‘fast burn’ relates to an individual’s physical peak. If you accept the idea that human physicality, (athleticism) in its rawest form rises steadily towards an apex, and then, just as steadily starts to decline, then, if the ‘fast burn’ training curriculum meshes with that rise and enhances the potential of the trainee, that has to be a good thing.

In ‘fast burn’ training, specialism can become a strength. This specialist skill-set might be in a particular zone, like ground fighting and grappling, or systems that specialise in kicking skills.

The down side.

However, over-specialisation can severely limit your ability to get yourself out of a tight spot, particularly where you have to be flexible in your options. Add to that the possibility that displaying your specialism may also reveal your weaknesses to a canny opponent.

It has to be said that a limited number of techniques whose training objectives are just based upon ‘harder’, ‘faster’, ‘stronger’ may suffer from the boredom factor, but, by definition, as ‘fast burn’ systems they may well top-out before boredom kicks in and just quit training altogether. They may well be the physical example of what the motor industry would call ‘built-in obsolescence’. [2]

Not that a martial art should be judged by its level of variety.

As a footnote; it is a known fact that in some traditional Japanese Budo systems students were charged by the number of techniques presented to them, so it was in the master’s interest to pile on a growing catalogue of techniques. I am not saying this was standard practice, but it certainly existed.

Slow Burn.

Turning my attention now to ‘slow burn’.

By definition ‘slow burn’ martial arts systems develop their efficiency over a very long time, or perhaps time as a measure is misleading? Maybe it would be better to describe the work needed to become a master of a ‘slow burn’ system as prolonged and arduous, perhaps beyond the bounds of most individuals.

For me ‘slow burn’ is defined by its complexity and sophistication and is associated with systems that have demanding levels of study, probably involving insane amounts of gruelling and boring repetitions that would test the ability (or willingness) of the average person to endure.

The positive side.

The up-side of this methodology is difficult to map as so few individuals ever get to the level of mastery and all we are left with are martial arts myths, but it would be foolish to dismiss it on these grounds alone. Most myths contain a kernel of truth and if a fraction of the myths told can be effectively proved or verified then really, there is no smoke without fire.

Looked at through the lens of modern sporting achievement, I think we can all appreciate that with the very best elite sportspeople uncanny abilities can be observed, and we know that despite the fact that many of them are blessed with unique genetic and physical disposition, an insane amount of work goes on to achieve these lofty heights (I am thinking of examples in tennis or golf, but really it applies to any top-level human endeavour – think of musicians!).

‘Slow burn’ martial arts systems may not comply with modern sports science used by elite athletes, but they were getting results any way, probably from a form of proto-sports science developed through generations of trial and error.

The ‘slow burn’ systems seem to be characterised by a reprogramming of the body in ways that require great subtlety, so subtle in fact that the practitioner struggles to comprehend the working of it even within their own bodies; it works by revelation and is holistic in nature. Mind and cognition are major components. The determination and grit that fuel the ‘fast burn’ systems are not enough to make ‘slow burn’ work, something more is needed; a reframing and reconfiguring of what we think we are doing.

Weaknesses.

The weaknesses of the ‘slow burn’ systems are pretty obvious.

Who has the time or patience to involve themselves in this level of prolonged study? It certainly doesn’t easily mesh with the demands of modern living; an awful lot of sacrifices would need to be made. It is no exaggeration to say that you would have to live your life as a kind of martial arts monk, casting aside comforts and ambitions outside of martial arts training. I often wonder how it was achieved in the historical past; I guess that beyond just living and surviving they had less distractions on their time than we do now. [3].

We know something of these systems because we can observe how, over time, the surviving examples had a tendency to morph into something altogether different; often taking on a new and reformed purpose, which of course improved their survival rate.

The examples I am thinking of have reinvented themselves as either health preserving exercise or semi-spiritual arbiters of love peace and harmony; all positive objectives in themselves and certainly not something we need less of in these current times.

I am going to duck that particular argument; it is not a rabbit hole I am keen to go down in this current discussion.

‘Slow burn’ dances with the devil when it too eagerly embraces its own mythologies; but in the absence of people who can really ‘do it’ what else have they got left? What always intrigues me is that the luminaries of the current crop of ‘slow burn’ masters are so reluctant to have their skills empirically tested. [4]

It is tempting, but it would be wrong to play these two extremes of the spectrum off against each other; I have deliberately focussed on the polar opposites, but it’s not ‘one or the other’, there are martial arts systems that are scattered along the continuum between these two extremes, and then there are others that have become lost in the weeds and suffer from a kind of identity crisis; aspiring to ‘slow burn’ mythologies while employing solely ‘fast burn’ methodologies. Can a man truly serve two masters? Or is the wisest thing to do to step back and ask some really searching questions? What is this really all about?

And Wado?

And, as this is a Wado blog, where does Wado fit in all this? I’m not so sure that the image of the line or spectrum between the two polar opposite helps us. I suppose it comes down to the vision and understanding of those who teach it – certainly there is a salutary warning illustrated by the weaknesses of both ‘Fast and Slow burn’.

Perhaps the ‘Fast Burn Slow Burn’ theory can be looked at through another lens, particularly as it relates to Wado?

For example, there is the Omote/Ura viewpoint.

To explain:

In some older forms of Japanese Budo/Bujutsu you have the ‘Omote’ aspect – ‘Omote’ suggests ‘exterior’, think of it like your shopfront. But there is also an ‘Ura’ dimension, an insider knowledge, the reverse of the shopfront, more like, ‘under the counter’, ‘what’s kept in the back room’, not for the eyes of the hoi polloi. The Ura is the refined aspect of the system.

I have heard this spoken about by certain Japanese Wado Sensei, and I have seen specific aspects of what are referred to as ‘Ura waza’, but these seem to range from the more simple hidden implications of techniques, to the seemingly rarefied, esoteric dimension; fogged by oblique references and maddening vagaries, to me they seem like pebbles dropped in a pond, hints rather than concrete actualities.

This of course begs the question; what is the real story of the current iterations of Wado as we know it? I will leave that for you to make your mind up about.

Maybe Wado is about layers?

Problems.

If we return to the original statement, “…all martial arts are about solving the same problem – protection/reaction against human physical aggression”. Ideally the success of the system should be judged by that particular measure, but clearly there is a problem with this, in that empirical data is virtually impossible to find. So how do most people create their own way of judging what is successful and efficient and what isn’t? All we are left with is opinion, which tends to be qualitative rather than quantitative. [5].

Outliers.

Let me throw this one in and risk sabotaging my own theory.

To further complicate things; a good friend of mine is a practitioner of a form of traditional Japanese Budo that that arguably and unashamedly has only one single technique in its syllabus! Yes, only one! My friend is now over 70 years old and has been practising his particular art for most of his adult life. I doubt that for one minute he would consider what he does as ‘fast burn’. I will leave you to work out what his system is, but it is no minor activity, (it is reputed to have over 500,000 practitioners worldwide!)

Tim Shaw

[1] I recently read a comment from an ex-military person who said that relying on unarmed combat in a military situation was ‘an indication that you’d f***ed up’. He said that military personnel relied on their weaponry, if you lost that you were extremely compromised. Also, he added that military personnel worked as a unit and that it is unlikely that a solo unarmed combat scenario would happen. Of course, we know that there are outliers and odd exceptions, but, as a rule… well, it’s not my opinion, it’s his.

After seeing the recent demonstration by North Korean ‘special forces’ in front of their ‘glorious leader’, basically the usual rubbish that you see from the ‘Essential Fakir Handbook’, you have to wonder who these people are kidding? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pv3L2knNodU

It’s just an opinion; not necessarily my opinion; other opinions are available.

[2] ‘Built-in Obsolescence’ Collins Dictionary definition = “the policy of deliberately limiting the life of a product in order to encourage the purchaser to replace it”.

[3] The sons and inheritors of the Tai Chi tradition of Yang Lu-ch’an (1799 – 1872) initially struggled to live up to their father’s punishing and prolonged training regime; Yang Pan-hou (1837 – 1892) tried to run away from home and his brother Yang Chien-hou (1839 – 1917) attempted suicide!

‘Tai-chi Touchstones – Yang Family Secret Transmissions’ Wile D. 1983.

[4] There was a ‘Fight Science’ documentary a few years back which looked at the claims of ‘slow burn’ martial systems and it didn’t come out well. The ‘master’ of the system was actually in very weak physical shape (largely due to smoking) although he had some well-organised physical moves and coordinated his operating system well. The truth was, he was a not the best of advocates, and for it to be truly scientific it needed many more contributors.

[5] I have another blog post planned on this theme. I fear it might ruffle a few feathers though.

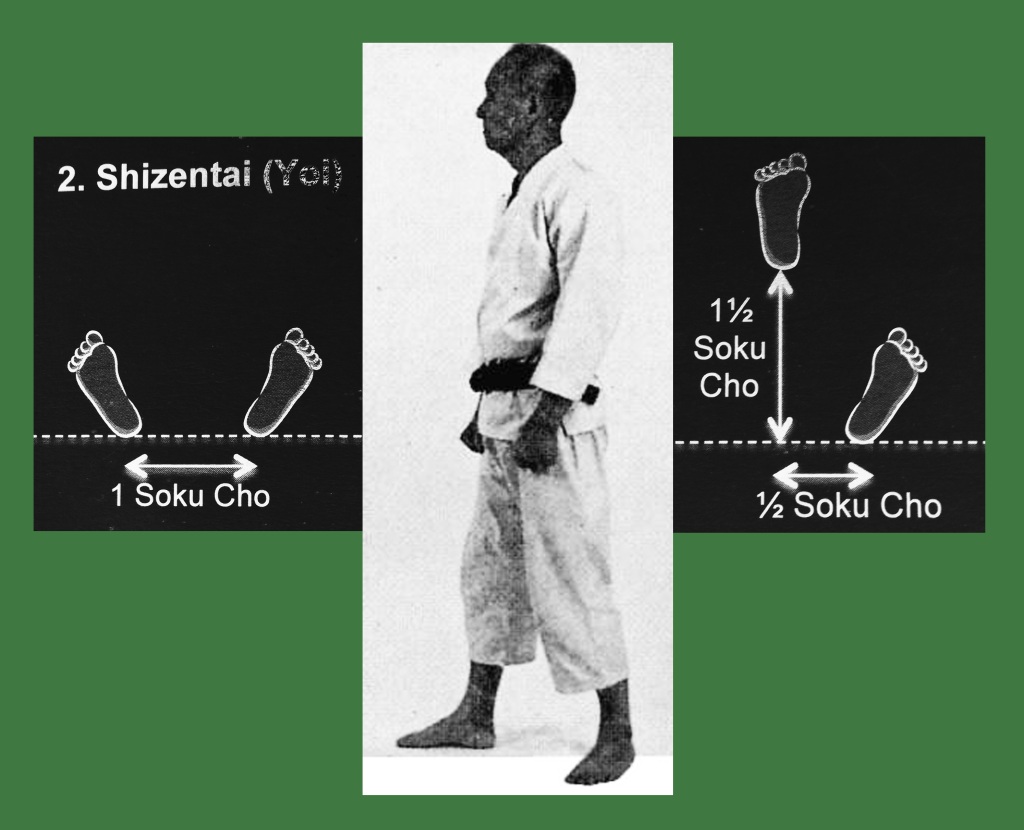

Shizentai.

Look through most Wado syllabus books and a few text books and you are bound to see a list of stances used in Wado karate; usually with a helpful diagram showing the foot positions.

One of the most basic positions is Shizentai; a seemingly benign ‘ready’ position with the feet apart and hands hanging naturally, but in fists. It is referred to as ‘natural stance’, mostly out of convenience; but as most of us are aware, the ‘tai’ part, usually indicated ‘body’, so ‘natural body’ would be a more accurate fit. [1].

In this particular post I want to explore Shizentai beyond the idea of it being a mere foot position, or something that signifies ‘ready’ (‘yoi’). There are more dimensions to this than meets the eye.

Let me split this into two factors:

- Firstly, the very practical, physical/martial manifestation and operational aspects.

- Secondly, the philosophical dimension. Shizentai as an aspiration, or a state of Mind.

Practicalities.

The physical manifestation of Shizentai as a stance, posture or attitude seems to suggest a kind of neutrality; this is misleading, because neutrality implies inertia, or being fixed in a kind of no-man’s land. The posture may seem to indicate that the person is switched off, or, at worst, an embodiment of indecisiveness.

No, instead, I would suggest that this ‘neutrality’ is the void out of which all possibilities spring. It is the conduit for all potential action.

Isn’t it interesting that in Wado any obvious tensing to set up Shizentai/Yoi is frowned upon; whereas other styles seem to insist upon a form of clenching and deliberate and very visual energising, particularly of the arms? As Wado observers, if we ever see that happening our inevitable knee-jerk is to say, ‘this is not Wado’, or at least that is my instinct, others may disagree.

Similarly, in the Wado Shizentai; the face gives nothing away, the breathing is calm and natural, nothing is forced.

In addition, I would say that in striking a pose, an attitude, a posture, you are transmitting information to your opponent. But there is a flip-side to this – the attitude or posture you take can also deny the opponent valuable information. You can unsettle your opponent and mentally destabilise him (kuzushi at the mental level, before any physical contact has happened). [2]

Shizentai as a Natural State – the philosophical dimension.

I mentioned above that Shizentai, the natural body goes beyond the corporeal and becomes a high-level aspiration; something we practice and aim to achieve, even though our accumulated habits are always there to trip us up.

In the West we seem to be very hung up on the duality of Mind and Body; but Japanese thinking is much more flexible and often sees the Mind/Body as a single entity, which helps to support the idea that Shizentai is a full-on holistic state, not something segmented and shoved into categories for convenience.

This helps us to understand Shizentai as a ‘Natural State’ rather than just a ‘Natural Body(stance)’.

But what is this naturalness that we should be reaching for?

Sometimes, to pin a term down, it is useful to examine what it is not, what its opposite is. The opposite of this natural state at a human level is something that is ‘artificial’, ‘forced’, ‘affected’, or ‘disingenuous’. To be in a pure Natural State means to be true to your nature; this doesn’t mean just ‘being you’, because, in some ways we are made up of all our accumulated experiences and the consequences of our past actions, both good and bad. Instead, this is another aspect of self-perfection, a stripping away of the unnecessary add-ons and returning to your true, original nature; the type of aspiration that would chime with the objectives of the Taoists, Buddhists and Neo-Confucians.

Although at this point and to give a balanced picture I think it only fair to say that Natural Action also includes the option for inaction. Sometimes the most appropriate and natural thing is to do nothing. [3]

Naturalness as it appears in other systems.

In the early days of the formation of Judo the Japanese pioneers were really keen to hold on to their philosophical principles, which clearly originated in their antecedent systems, the Koryu. Shizentai was a key part of their practical and ethical base. [4] In Judo, at a practical level, Shizentai was the axial position from which all postures, opportunities and techniques emanated. Naturalness was a prerequisite of a kind of formless flow, a poetic and pure spontaneity that was essential for Judo at its highest level.

Within Wado?

When gathering my thought for this post I was reminded of the words of a particular Japanese Wado Sensei. It must have been about 1977 when he told us that at a grading or competition he could tell the quality and skill level of the student by the way they walked on to the performance area, before they even made a move. Now, I don’t think he was talking about the exaggerated formalised striding out you see with modern kata competitors, which again, is the complete opposite of ‘natural’ and is obviously something borrowed from gymnastics. I think what he was referring to was the micro-clues that are the product of a natural and unforced confidence and composure. For him the student’s ability just shone through, even before a punch was thrown or an active stance was taken.

This had me reflecting on the performances of the first and second grandmasters of Wado, particularly in paired kata. On film, what is noticeable is their apparent casualness when facing an opponent. Although both were filmed in their senior years, they each displayed a natural and calm composure with no need for drama. This is particularly noticeable in Tanto Dori (knife defence), where, by necessity, and, as if to emphasise the point, the hands are dropped, which for me belies the very essence of Shizentai. There is no need to turn the volume up to eleven, no stamping of the feet or huffing and puffing; certainly, it is not a crowd pleaser… it just is, as it is.

As a final thought, I would say to those who think that Shizentai has no guard. At the highest level, there is no guard, because everything is ‘guard’.

Tim Shaw

[1] The stance is sometimes called, ‘hachijidachi’, or ‘figure eight stance’, because the shape of the feet position suggests the Japanese character for the number eight, 八.

[2] Japanese swordsmanship has this woven into the practice. At its simplest form the posture can set up a kill zone, which may of may not entice the opponent into it – the problem is his, if he is forced to engage. Or even the posture can hide vital pieces of information, like the length or nature of the weapon he is about to face, making it incredibly difficult to take the correct distance; which may have potentially fatal consequences.

[3] The Chinese philosopher Mencius (372 BCE – 289 BCE) told this story, “Among the people of the state of Song there was one who, concerned lest his grain not grow, pulled on it. Wearily, he returned home, and said to his family, ‘Today I am worn out. I helped the grain to grow.’ His son rushed out and looked at it. The grain was withered”. In the farmer’s enthusiasm to enhance the growth of his crops he went beyond the bounds of Nature. Clearly his best course of action was to do nothing.

[4] See the writings of Koizumi Gunji, particularly, ‘My study of Judo: The principles and the technical fundamentals’ (1960).

The Martial Body.

Physical culture and martial arts have always been inseparable. Your physical properties/qualities have to aspire towards being the nearest match to the tasks you are expected to perform.

For me this throws up several questions:

So, how does that come about?

Are those physical properties a product of the training itself?

Am I perhaps talking about utilitarian strength versus strength for strength’s sake?

How strong do you have to be?

How is ‘strength’ defined within the traditional martial disciplines (is ‘strength’ even the right word, or the right measure)?

I am not going to get into the discussion about the merits of supplementary strength training; instead, I want to explore the subject through a very specific example.

Kuroda Tetsuzan Sensei.

In past posts I have made reference to Kuroda Tetsuzan Sensei, a modern day Japanese martial arts master, very much of the old school. Kuroda has an impeccable reputation amongst martial arts specialist who ‘know’. His ability is astounding.

He is the inheritor of the Shinbukan system which contains five disciplines within its broader curriculum; including the sword and its own Jujutsu system.

Kuroda has been a touchstone for me; the YouTube snippets have me totally spellbound; I have watched them so many times. Published interviews contain amazing insight and his ideas chime very closely to things I have heard in well-informed Wado circles.

This post is inspired by an extensive interview Kuroda Sensei gave in 2010 (published by Leo Tamaki ) and, to develop my theme I will make specific references to points made within the interview.

What really interested me was Kuroda Sensei’s back-story; the environment he was raised in as it related to the martial arts. Starting at the family home. In the interview Kuroda suggests that it was virtually impossible for him to avoid the all-pervading atmosphere of traditional Budo; it was as natural and essential to him as oxygen; in his domestic setting the noises of training were as much a part of his environment as birdsong.

In the interview Leo Tamaki does an excellent job of trying to pin Kuroda down to specifics about the physical side of the training, (I almost get the impression that Tamaki had tried to second guess the answers and that maybe Kuroda’s replies took him by surprise).

Kuroda’s father, grandfather and great uncle were brought up as martial artists of the old school, and, at the family home where they trained, there was only a thin partition between the living area and the small Dojo. In the interview, Kuroda Sensei made a reference to the physical qualities of these men:

“When we look at my grandfather’s body, or his brother’s we are impressed. But it is a body they have developed and acquired by training days and nights since their youngest age, using the principle of not using strength.

They did not develop it by lifting rocks, climbing mountains or carrying branches. (Laughs) It is by relentlessly practising without strength that they developed such thick arms. And this is a truly remarkable work.

Developing such a body without using strength requires unbelievable amount of training. It’s generally something developed only by intensive practice started very early in life. Being born in a martial arts masters’ house, they practised all day while students came and went. At the time, after a day of training without using strength it occurred that my grandfather could not hold his chopsticks any more and needed someone to wrap his fingers around.”

My view is that technique over strength develops its own brand of strength, a purely utilitarian strength. Picture a 19th century blacksmith who earns his daily bread by heating and hammering metal all day, and has done so since he was a boy big enough to hold a hammer, the body fashions itself throughout the craftsman’s lifetime, no artifice, no vanity. I once saw a photograph of a generation of blacksmiths, father, son and grandson, standing proudly outside of the forge, meaty forearms folded across their broad cheats, proud of their labours with probably no concern about their bodies; these were certainly not the same as the contemporary tattooed, preening metrosexuals to be found propping up the bar in your local bistro. This was functional muscle.

With Kuroda’s antecedents it wasn’t the ‘hours’ spent in the Dojo, it was the ‘years’ of day to day training that made the difference.

But it is Kuroda’s description of relaxed strength, a nuanced strength that transforms the body almost by stealth, that caught my attention. He describes his grandfather’s handling of the sword as being ‘light’, but he also tells tales of his grandfather’s ability in cutting, even with a blunt sword!

The interviewer further pursues his theme of practicing with strength, asking, “Can or should beginners then practise with strength and power?”

The answer is:

“In absolute terms, it is not really a problem that they practise like this. But by doing so, it is very difficult to evolve and progress to another practice. In an era where we have less and less time, and where we can only allocate a few hours per week or month, it is impossible to enter another dimension of practice by training like that.

This is why I teach the superior principles to my students, from the beginning. I also require them to absolutely practise without using strength. If we use strength, we are directly in a very limited work. By receiving these teachings from the beginning, it is normal to put them straight into application”.

Effectively he is trying to square the circle of people not having the time to train as people did in the old days but still needing to reach to the higher levels of attainment. The ‘strength’ issue just side-tracks the development. His attitude seems to be to introduce people to the importance of the core principles first, because at least then they can start to work it out with some element of time on their side.

He’s not against strength as such, I just think he’s very careful in his definitions, particularly about the application of strength.

Again, for me this rings bells. Thinking about my own early experiences of Wado, I am fairly sure the cart was placed before the horse, and then subsequently I had to spend an awful lot of time and effort deprogramming myself and learn to appreciate the importance of ‘principle’. To paraphrase a friend of mine, ‘We learned our karate back to front; we learned to punch and kick first and then we learned to use our body; it should have been the other way round!’ [1].

Newcomers to martial arts training, particularly men, have an image in their heads (and in their bodies) of what ‘strength’ looks and feels like. As an instructor, I have to try to unravel this fallacy, and even though they understand it in their heads it is stubbornly hard-wired into their bodies. With time and patience, it can be undone, but it takes a lot of dogged determination on the part of the instructor and the student to do it. Interestingly women do not seem so encumbered by this type of baggage; for me, this makes women easier to teach and gives them greater potential to fast-track their development.

I am certain that there is much more mileage in this area, but I think that Kuroda Sensei’s insights give us a glimpse into the past and the mindset of the Japanese martial artists of the old school.

Tim Shaw

Image of Kuroda Sensei, courtesy of; http://budoinjapantest.blogspot.com/2013/11/kuroda-tetsuzan.html

[1] He won’t mind me mentioning him, but credit for this comment goes to the irrepressible Mark Gallagher. Once met, never forgotten.

Wado on Film (Anything on film!) – Part 1.

On the surface it would appear that we are blessed to have so much film of the founder of Wado Ryu available to us. It is lucky that Otsuka Hironori was not camera shy and showed enough foresight to actually have himself recorded with the intention of securing the legacy of his techniques and ideas for future generations. I have heard that there is even more unseen material that has been archived away, held secure by his inheritors.

Although it is interesting that there seem to be zero examples of film of Otsuka Sensei as a younger man; while there are photographs a plenty. (Otsuka Sensei was born in 1892 and only passed away in 1982).

He appeared to hit his filmic stride in his mid-seventies. Although a while back, a tiny snippet of footage of the younger Otsuka did appear as almost an afterthought on a JKA Shotokan film. It was a bare couple of seconds, it certainly looked like him – he was demonstrating at some huge martial arts event in Japan; the year is uncertain, but I am guessing some time in the 1950’s. In this film there was an agility and celerity to his movements which is not so evident in his later years. [1]

Historically, it does seem odd that there is so little film available from those years of such a celebrated martial artist.

Ueshiba Morihei, the founder of Aikido has a film legacy that goes back to a significant and detailed movie shot in 1935 at the behest of the Asahi News company. Ueshiba was then a powerful 51-year-old, springing around like a human dynamo, it’s worth watching. [LINK]

On first viewing that particular film it left me scratching my head; initial examination told me that the techniques looked so fake. But the more I watched, there were individual moments where some strange things seemed to happen (at one point his Uke is propelled backwards like an electric shock had gone through him). At times Uke seems to attempt to second-guess him and finds himself spiralling almost out of control. Really interesting.

But for Wado, is this even important? Why does it matter? Afterall, Wado Ryu had already been launched across the world, much of which happened during Otsuka Sensei’s lifetime. Also, the first and second generation instructors were doing the best of a difficult job to channel Otsuka Sensei’s ideas.

So, what can we gain from watching flickering images of master Otsuka showing us the formalised kata or kihon? What value does it have?

I saw Otsuka Sensei in person in 1975. I watched in awe his demonstration on the floor of the National Sports Centre, Crystal Palace in London. I was only seventeen years old. I remember thinking at the time, ‘here is something very special going on in front of my eyes – I know that – but I can’t put my finger on exactly what it is’.

At that age and the particular stage of my development, I had very little to bring to the experience. I lacked the tools. Possibly the only advantage I had at that time was I was carrying no baggage, no preconceptions; maybe that is why the memory has stayed so clear in my mind [2].

Interestingly, Aikido founder master Ueshiba’s own students, in later interviews lamented that they wished they’d paid more attention to exactly what he was doing when he was demonstrating in front of them; even when he laid hands upon them, they still struggled to get it.

Can we ever hope to bridge the gap?

I think it is useful to acknowledge the problem. The reality is that we are THERE but NOT THERE; we are SEEING but not SEEING. I believe that we often lack the refined tools to understand what is really going on and what is really useful to us as developing martial artists. It comes down in part to that old ‘subjectivity’ versus ‘objectivity’ problem; can we ever be truly objective?

But it is the evanescence of the experience; it flickers and then it is gone and all we are left with is a vain attempt to grasp vapour. But isn’t that the essence of everything we do as martial artists?

To explain:

Two forms of artefact.

I read recently that in Japanese cultural circles they acknowledge that there are two forms of artefact; ones with permanence, solidity and material substance, and ones with no material substance, but both of equal value.

The first would include paintings, prints, ceramics and the creations of the iconic swordsmiths. For example, you can actually touch, hold, weigh, admire a 200 year old Mino ware ceramic bowl, or a blade made by Masamune in the early 14th century – if you are lucky enough. These are real objects made to last and to be a reflection of the artist’s search for perfection; they live on beyond the lifetime of their creator.

But the second, only loosely qualifies as an artefact as it has no material substance, or if it does it has a substance that is fleeting. This is part of the Japanese ‘Way of Art’ Geido.

There are many examples of this but the best ones are probably the Tea Ceremony (Sado) and Japanese Flower Arranging (Kado). Even the art of Japanese traditional theatre which is so culturally iconic actually leaves no lasting material artefact.

In the Tea Ceremony the art is in the process and the experience. Beloved of its practitioners is the phrase, ‘Ichi go, Ichi e’ which means ‘[this] one time, one place’.

The martial arts also leave no material permanence behind. Their longevity and survival are based upon their continued tradition (this is the meaning of ‘Ryu’ as a ‘stream’ or ‘tradition’, it seems to work better than ‘school’). The tradition manifests itself through the practitioners and their level of mastery; this is why transmission is so important. But a word of caution; the best traditions survive not in a state of atrophy, but as an evolving improving entity. It is all so very Darwinian. Species that fail to adapt to a changing environment and just keep chugging on and doing what they always do soon become extinct species.

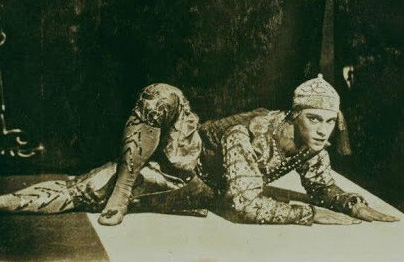

Film (Nijinky, a case history).

Vaslav Nijinsky (1890 – 1950) was the greatest male ballet dancer of the 20th century. He was probably at his majestic peak around about 1912 as part of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. To his contemporaries Nijinsky was a God; he could do things other male dancers could only dream of; he danced on pointe and his leaps almost seemed to defy gravity. As this quote from the time tells us:

“An electric shock passed through the entire audience. Intoxicated, entranced, gasping for breath, we followed this superhuman being… the power, the featherweight lightness, the steel-like strength, the suppleness of his movements…”.

But, there was never any film made of this amazing dancer, so, all we have left are these words. Even though, at the time, movie-making was on the rise (D. W. Griffith was knocking out multiple movies in the USA in 1912 and earlier). At the time the dance establishment distrusted the new medium of moving pictures, they feared that it trivialised their art and turned it into a mere novelty; which clearly proved to be incredibly short-sighted.

If Nijinsky, arch-performer, had anything to teach the world of dance it is lost to us. Incidentally it is said that Nijinsky destroyed his mind through the discipline of his body. He ended his days in and out of asylums and mental hospitals.

We will never know how good Nijinsky was in comparison to modern dancers, or if it was all a big fuss about nothing. But then again, the very same could be said about any famous performer, sportsperson or martial artist born before the invention of moving pictures.

Other forms of recollections or records that act as witnesses.

A writer or composer leaves behind another form of record. For composers before the first sound recordings in 1860 it was in the form of published written music or score. We would assume that this would be enough to contain the genius of past musicians?

But maybe not.

Starting right at the very apex of musical genius, what about Mozart?

Well, maybe those written symphonies, operas etc. were not a faithful reflection of the great man? Certainly, there is some dispute about this. There has been a suggestion that rather like the plays of Shakespeare, all we have left are stage directions, (with Shakespeare the actors slotted in whatever words they thought were appropriate!).

We judge Mozart not only by todays orchestral/musical performances, but also by his completed score on the page, and some may see these pages as a distillation of Mozart’s genius; but perhaps Mozart’s real genius was expressed through something we would never see written down, thus, today, never performed? This was his ability to improvise and elaborate around a stripped-back musical framework. It is reported that he was able to weave his magic spontaneously. As an example, Mozart was known to only write the violin parts for a new premier performance, allowing the piano parts, which he was to play, to come straight out of his head. We have no idea how he did it, or what it might have sounded like.

More on this developing theme in the second part. What point is there to all this chasing of shadows? Are we kidding ourselves? Can we be truly objective to what we are seeing?

Part 2 coming shortly.

Tim Shaw

[1] If anyone is able to track down this piece of film, I would be grateful if they would let me know the URL. It seems to have disappeared from YouTube, or my search skills are not what they used to be.

[2] This was the same year as the IRA bomb scare, as well as Otsuka Sensei getting the back of his hand cut by his attacker’s sword.

Image of Nijinsky (detail). Nijinsky in ‘Les Orientales’ 1911. Image credit: https://www.russianartandculture.com/god-only-knows-tate-modern/

Smoke and Mirrors.

It is said that magic ceases to be magic once it is explained; although the late fantasy author Terry Pratchett contradicted this with, “It doesn’t stop being magic just because you know how it works.” I think I know what he means.

At an objective and scientific level this is the difference between the ‘natural’ and the ‘supernatural’.

Martial art skills often appear to be supernatural, where the masters are in possession of abilities that seem to be out of reach for the average person in the street; this is part of the mystique, a million fantasies have been built on this idea.

However, there are times when refined and developed technique seems to confound the mind and contradict the physical world, whether it’s Bruce Lee’s one-inch punch or Aikido’s ‘unbendable arm’ (See my previous blog post ‘On Things ‘Chi’ and ‘Ki’’).

Without allowing myself to be diverted, there has been some quiet rumblings about the more subtle aspects of Wado technique and, for the cognoscenti, a suggestion perhaps that there is more going on under the hood than the recent Gendai Budo incarnations seem to imply. And, as such, I want to shine a light into an obscure oddity that may have a peripheral connection to aspects of Wado technique (as I understand them), via a tortuous route – please bear with me.

I have been sitting on this for quite some time and thought I would share it with you*. It may be nothing, it may be something. It may even be an excellent illustration of the human capacity for boundless curiosity, and what can come out of it. You can make your own mind up.

Lulu Hurst was to all intents and purposes, outwardly an unremarkable young woman, born in Polk County, Georgia USA in 1869, daughter of a Baptist preacher, but overnight, as a teenager, she became a high earning freakish phenomenon who confounded the paying public with her jaw-dropping feats.

Dubbed ‘The Georgia Wonder’ she performed impossible acts of human strength. When asked where her skills came from the slightly built Lulu said they came as a result of her being caught in an electric storm, she was a supernatural human miracle. Even the great Harry Houdini was initially puzzled as to where this phenomenal strength came from.

Lulu was able to take the weight and strength of a number of men, often through a chair or a staff, and with only a light touch displace the resisting men. She was often completely immovable, no matter how much pressure was applied. When I first heard this story it started ring bells with me; where had I come across similar phenomena?

And then I recalled stories, anecdotes of comparable abilities being demonstrated by the founder of Aikido Ueshiba Morihei. He would hold out a Jo and ask his students to try and move it – sounds easy, but try as they might they couldn’t shift it. No explanations were given, or if they were, they were shrouded in mystical obfuscation.

Over time more of these unexplainable phenomena appeared on my radar – even with the possibility of conscious or unconscious compliance it seemed that there was something there.

But Lulu retired after only two years; she’d made her money and at the tender age of sixteen she ran off and married her manager.

Years later Lulu admitted what she had really been up to; which in my mind was no less of a wonder, but certainly there was no magical ‘electrical storm’, something much more ‘grounded’ was at work.

She finally confessed it all in her autobiography. It wasn’t the product of some great revelation; she just came across it by accident.

Her first realisation was when she held a billiard cue horizontally in front of her at chest height and invited someone to push with all their might, to try and knock her over; they couldn’t! She developed it to such a degree that a whole bunch of hefty guys could push on it and STILL couldn’t dislodge her! Then she really got into showmanship, and performed the same trick standing on one leg!

From this beginning she developed a whole array of ‘tests of strength’. What is surprising though is that initially even she didn’t know how it was done.

She was smart enough to deny the supernatural and set about studying what was really going on. The level to which she was puzzled by her own ability is illustrated by the fact that her manager/husband had asked her repeatedly to teach him how to do it, but she couldn’t, because she didn’t know herself.

Finally, she did figure it out, through studying mechanics and physics. To keep it really simple the first trick, with the billiard cue, came out of her ability to read and direct the energy of the resistance and send it into… nothing, the men were not engaging with her at all.

Houdini spotted it, but it took him a while. As the master of illusion and physical manipulation himself, it was only a matter of time.

She became more adept at these forms of manipulation, and added all of this to her act.

Does this make Lulu Hurst any less remarkable? No, not in the least.

You can read her autobiography for yourself, but be warned, it’s a slog of a read, couched in the flowery language of the time. It is called, predictably and unimaginatively; ‘Lulu Hurst (The Georgia Wonder) Writes Her Autobiography’ 1897.

To reiterate; human curiosity and the ability to explore and expand beyond the realms of what is normally accepted really does know no bounds.

Tim Shaw

*The first time I ran this idea by anyone was in communication with a now disgraced famous UK karate historian back in the 1990’s. He seemed to think I was on to something.

Photo credits:

Illustration of Lulu Hurst chair act, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 26th, 1884. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/file/11051

Black and white photographs of Lulu Hurst: credit, ‘Lulu Hurst (The Georgia Wonder) Writes Her Autobiography’ 1897. Free of restrictions on copyright.

“Why does every lesson feel like ‘day one’?”

Reflections on how karate students sometimes struggle to grasp the idea that they are progressing and improving.

When you are sat on an aeroplane; comfy and strapped into your seat; alongside lots of other people who are also passively settled in their own seats; have you ever thought about the wonderful contradiction you are experiencing? There you all are, row upon row of people, not going anywhere. But just glance at the flight progress animation in the little screen in front of you (long haul of course) and think of the vastness of the planet and the distance your plane has travelled in the last hour and then tell yourself you are not going anywhere. Of course, it’s all so ridiculous and obvious and easily dismissible.

I know everything is relative; as Heraclitus said, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man”. So why do karate students sometimes get the feeling that every lesson is like day one? Why is it so difficult sometimes to observe your own progress?

Of course, it is entirely possible that no progress has been made; what is it they say, “If you always do what you always do, you’ll always get what you always get”. But, as a quote, it’s a bit of a blunt instrument. It might just be that progress is so slow that it is barely perceptible, like the hands of a clock.

There was a Dojo I used to visit quite regularly in the early 1990’s which had the same membership for many years; but when opportunities came to advance came along, be it through gradings or something else, the students shrank away. Yet week after week they came back and did the same session. Oh, they would work hard and they loved what they were doing but they just stayed the same, they never improved. Whether they thought that the penny would eventually drop, or that maybe they learned by osmosis, or whether they were just keeping fit, I never knew, they just never improved.

But then there is the other type of Dojo; which also has regular membership and attendance, coming back week after week. But, maybe, lurking at the back of their minds could be some personal doubt, “Why does it feel like I am not improving? Come to think of it, why does it feel like nobody in the Dojo is improving?” Maybe they fail to see what is right under their noses. Like the passengers in the plane, they are all there together, all on the same ride, shoulder to shoulder and all moving forward as one; all developing on their journey almost in step, in unison.

But for them, the clues are there to be found. A visitor comes to the Dojo, someone who was there a year earlier and says, “I saw these same people here a year ago – wow, haven’t they improved!”

These same students find that on bigger courses they measure up well against people of the same grade, and, as such feel pride swell in their chests. They put themselves in for grading examinations and they pass! They enter competitions and they do well!

But sometimes they still doubt themselves. In the competition, they could say to themselves, “Maybe I was just lucky that day”. In the grading, “I feel that I didn’t deserve that pass, why did they let me have it? I wasn’t even on top form”, but nobody is ever on ‘top form’! Competition wins are rarely ‘life defining’ and, as for gradings, they are just endorsements and markers along the way, neither of these are ends in themselves. If your sole objective is the next belt, or winning ‘that’ competition I would seriously question why you are even doing martial arts?

Sometimes karateka slip into the trap of Imposter Syndrome, (Definition: “a psychological pattern in which an individual doubts their skills, talents or accomplishments and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud”.”) I wrote about this in my previous blogpost about the ‘Dunning Kruger Effect’. A crucial element of this is that sometimes the karateka doesn’t feel like she is progressing because she is no longer in the company of inept amateurs. She is in the world of people just like her, well-practiced and skilful, and also, if she is lucky, in the company of those who are better than her, which acts as an incentive and a draw to push her to excel. Experiences and environments like that keep her constantly on her toes; this is the zone of growth.

It’s all a matter of perspective.

Happy travels.

Tim Shaw

Can a martial art ever be taught as an algorithm?

Currently algorithms tend to be the fall-guys for all that is wrong in the world. People always leap towards the worst possible examples, like; would you every want a computer algorithm deciding who gets medical intervention, or is refused based on a calculated outcome? To some people algorithms ARE Skynet!

But, taken in the broadest definition we use some form of algorithm in many areas of life. In a nutshell it is ‘A’ leads to ‘B’, ‘B’ leads to ‘C’ or options branching off from any of the stages and it is really useful.

I ask this question in the context of martial arts because I have noticed a growth in algorithmic-style explanations of how some martial art systems work.

I can see the appeal of algorithms; they are accessible, predictable, understandable and communicable, all excellent things for a martial arts system to aspire to – the only weakness I see in terms of martial arts is that it’s really hard to make them measurable; but that’s for another discussion.

Building an algorithmic martial arts system is what you would do if you only had a very short period of time to prepare someone. A simplified system, stripped down, discarding all the inessentials (now where have we heard that before?). Four or five techniques repeated over and over until they are excellent would do the job. There are a number of obvious downsides to this; one being that its marketability is undermined by the boredom factor and the irony is that the ‘stripped down’ system has to build in greater complexity to make it interesting (more funky takedowns, armbars, gooseneck wrist locks etc.), and it turns into the one thing it was trying hard not to be.

In a way this follows on from a previous blogpost I had written; ‘Is your martial art complicated or complex?’

There are alternative approaches, but it depends on what your aspirations are – in fact it depends on a whole raft of things, including, how much time do you have available to invest in this? Where do your priorities lie in terms of what you want out of your martial art training? What system suits you both physically and mentally? (No, they are not all the same).

Something that is close to an algorithmic approach might be akin to taking a course in CPR or First Aid. In that instance you might be motivated by the worry of how you might be able to cope if you were unfortunate to arrive on the scene of an accident; would you be able to do the right thing? Lives might be at risk.

But let’s say you really wanted to dig deeper into this area, really wanted to become actively and positively involved in the saving of lives and human physical welfare. Surely then, if you had the opportunity and the inclination to do so you would study medicine? To do so would be to plunge deeply into what lies beneath the skin; even to looking at what operates at cellular level, with all the hours of dedication and years’ work that this involves. And for that to happen (as with all complexities) you have to go backwards before you go forwards, you have to turn over everything you thought you knew. In reality, this is a description of martial arts as a ‘Way’, a non-algorithmic ‘complex’ system; this is Budo.

Why would you want to put yourself through the long painful slog of a Budo system, one that is so arduous that you feel you are moving backwards instead of forwards, one where you are actually significantly weaker, structurally confused, coordinationally muddled and intellectually perplexed; in other words, not all that dissimilar to a first year medical student. Why would you do it?

To be clear; martial arts and everything associated with it is a physical conundrum that is engaged in by humans, not robots; fighting is not mechanistic, it is organic, it is a ‘complex system’. It is like swimming in the ocean, it’s not a two metre paddling pool.

A question that is often asked; just how do you engage with martial arts as a complexity; how does it actually work? I will have to be honest here; to answer that question I feel I really don’t have the qualifications, but I might offer some pointers. There are definitely guiding concepts that act like a map to keep you on the right road. But make no bones about it; knowing the concepts only in your head is about as useful as land swimming; this has to be done by the body and in as live a situation as is possible, while still remaining within civilised constraints of course.

To explain further:

The ‘complex’ martial art system differs from the algorithmic approach the same way that the chess computer AlphaZero was from its nearest rival Stockfish 8. For Stockfish all possible chess combinations were programmed in manually, while AlphaZero only learned the rules of chess (it took a mere 4 hours), AlphaZero then played itself through a phenomenal number of games to build up its stock of possibilities. It subsequently played a challenge match against Stockfish 8 and in a 100 games it never lost a single one. AI people say this is how human intelligence works. I would argue that this is how the ‘complex’ martial artist works. In algorithmic martial arts it’s pretty clear that you have to slip between modes, a bit like changing gear, but with a ‘complex’ Budo martial arts you are always in gear, because it’s built around a fundamental integral core of Principles, this is the nucleus of what you do, everything spirals out from that point; anything else is just nuts and bolts; even the funky takedowns, the armbars and the gooseneck locks.

The bad news is that you don’t read this stuff in a book, you don’t see it on YouTube and, unless you’ve got the eyes to REALLY see what’s going on, you certainly won’t find it in a one-off seminar.

Tim Shaw

Postscript: As an afterthought, Budo, like Medicine is not solely about the visceral stuff, both disciplines are underpinned by ethical, philosophical and moral considerations (in medicine it is reflected in the Hippocratic Oath).

Use it or lose it – Part 2.

After writing the initial ‘Use it or Lose it’ blogpost and listening to feedback, I realised there was more scope for exploration.

Right at the start I must say that I don’t hold myself up as an expert in this field, and I only have the layman’s understanding of the science behind the subject; so, as is often the case, all we are left with is opinion.

I will start by stating the very obvious; but it is useful to have these things nailed down to establish some kind of context, or framework.

It is clear that all living organisms have a limited shelf-life, and within that allotted time (which is in no way guaranteed) there is likely to be a physical peak which we as humans (hopefully) climb towards, this is sometimes referred to as our ‘prime’, and then we have to resign ourselves towards a steady slide into decline. It’s sad, but it has to be said.

What has always been of interest to me is how we manage this particular ‘allotted time’, specifically relating to our physicality. Do we stumble into an uncertain future and hope that our bodies follow some kind of unwritten innate game plan? Or should we perhaps be more proactive and realistic about how we want to develop and mature?

As I mentioned in the first blogpost, we are designed for movement; we are very good at it, well at least we start out being very good at it. Eventually, throughout our early development we emerge at the top of a very steep learning curve. Young children learn about movement through an amazing capacity to bounce back from failure and pure trial and error, while still remaining emotionally resilient they cope with adversity amazingly well, full of optimism and a ‘can-do’ attitude. If you think about it, it’s truly inspirational.

We all did it; we rode on the crest of a wave… and then the wave dropped flat and we descended into habitual modes of movement; for example; it’s much cooler to walk instead of run; take the lift rather than the stairs – there’s too much effort required to do otherwise, it’s a much smarter way of operating; or so we tell ourselves.

What happens to our youthful selves?

While still in the flush of youth we are corralled into institutionalised physical activity in schools, with one-size-fits-all P.E. lessons. For some people it worked; for the majority the wind was taken out of their sails and they had to navigate rules and regulations, militarised team structures, pecking orders, triumphs for a minority and potential humiliation for everyone else, and then, to add to the misery, a sizable majority found their ship colliding with the rocky coastline of puberty and body awareness of the most negative kind (particularly, though not exclusively, girls). The P.E. teachers I have met are always well-intentioned and very good at defending their corner of the curriculum; with talk of ‘team work’ and ‘life’s competitive realities’, they believe they supply a partial antidote to the snowflake generation. More progressive P.E. educationalists have tried to rethink what is essentially a 19th century mind-set but it’s like swimming against the tide.

But what happened to ‘play’? It always intrigued me how, in school gymnasiums and on sports fields the word ‘play’ (as in its most refined form) became redundant or even sneered at; unless, of course, it was used as a command.

Playfulness, the most valuable thing in children’s early development (of both mind and body) has been left behind. To ‘play’ is to explore. In its purest form it exists unashamedly in only a few disciplines.

Without apology or pretensions, musicians ‘play’, and when they get together they are inclined to indulge in ‘free play’, they might call it ‘jamming’ or free improvisation, a common thing with most musicians, particularly in jazz, but it’s still ‘play’ in the original meaning of the word. What is interesting about these musicians is that their freedom to play tends to come after a period of intense discipline, a prolonged apprenticeship. In the visual arts Picasso is supposed to have said something to the effect that you need to learn the rules well before you are allowed to break them. This does not mean it is the only path to the top of the mountain; some of the greatest musicians or visual artists achieved amazing expressive work without formal training, intuitively through play, unconstrained by boundaries.