Historical

Is Wado really a style of Karate?

I am publishing this post on here as an example of the more focussed articles I have lined up for the Substack project. My postings on Substack will eventually be on two levels; free content that comes out every week and content that can be accessed by a small paid monthly subscription, believe me, it will be worth it. If you haven’t already, sign up free for the project at, https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

Btw. If you are signed up and on Gmail, be wary that it has a habit of dropping Substack posts into the ‘Promotions’ folder.

On with the theme.

Everything has to fit into some kind of category; labels must be attached and pigeonholes have to be filled – otherwise how do we know what we are describing. It is a quick way to make sense of things, particularly if we want to communicate to other people what we are talking about.

The quick shorthand operates largely because we are in a hurry – someone asks, “What do you do with your evenings?”, answer, “I go to my karate class”. The conversation could end at that point, or the questioner might ask for more information, out of politeness or maybe they are genuinely interested. And that is your opportunity to volunteer more detail.

Do we want Wado to be called ‘karate’?

But we Wado people are likely to be entirely happy to allow what we do to be identified as ‘karate’. But, is Wado Ryu/Kai etc really karate? Maybe it is something else which has not been truly pinned down, like a newly discovered genus; a wild critter that is neither ‘dog’ nor ‘cat’, a kind of Tasmanian Tiger, but still kicking around, possibly even thriving? [1]

It is entirely possible that Wado sails under a flag of convenience? I have cousins who hold both US and UK citizenship and I can’t help noticing that when they are in the UK they fly the US flag and when in the USA they fly the British flag when it suits them (really noticeable when the accents change). With Wado it very much the same; being identified as ‘karate’ has opened many doors for them, but what about its other possible identifying qualities, what are the competing factions?

Let me try and lay out the case… with some provisos, I am not Japanese and I run the risk of looking at this from a very western viewpoint, so everything here is conjecture and opinion.

Let me start with the easy one:

Wado as Japanese Budo.

This is where we apply the national pride and cultural credentials to Wado. It has such deep roots that to explain it would be like trying to untangle spaghetti. This is the bigger ‘identity’ issue. ‘But Wado was only recognised as an entity in 1938’! – I hear you say. Maybe, but, as we will see, the complexity of the history of Japan’s own indigenous martial systems is not to be taken lightly, particularly as it applies to Wado.

Personally, I quite like the ‘Wado is a distinct form of very Japanese Budo’ angle; it ties it neatly to the unquestioning high cultural and moral characteristics of anything that falls into the category ‘Budo’. But, as we know ‘Budo’ is a broad grouping and can be annoyingly difficult to pin down, especially when it uses high-minded and sometimes vague terms in which to describe itself.

But the subtext here should not be skipped over too quickly – ‘distinctly Japanese’, we are now talking about Budo as a kind of cultural artefact, one that has to be wrapped in the flag. But ‘distinct from’ what?

Historically, indigenous Japanese arts have had their heyday, and since Japan took to embracing all things western, these ‘arts’ slipped in the category of anachronisms; they were considered out of step with the direction Japan saw itself going in. For industrial Japan there was no going back, and, it has to be said, the Japanese performed economic and technical miracles; certainly, pre WW2, where things then went more than a little sideways.

Then came a time when these ancient arts needed to either be rescued from decline or completely resurrected, and, in the marketplace for oriental martial arts they had to stand up for themselves and proclaim who they were. This ‘claiming of the national identity’ came a lot earlier than most people think; it could be said that ‘karate’ was the first skirmish in a culture war that was yet to happen.

To keep this brief; Karate was from Okinawa, with very strong cultural ties to China, one of the earlier incarnations of the characters used to write ‘karate’ was actually ‘Chinese Hand’, so effectively this was an imported system and, considering the rocky historical relationship between China and Japan (which was to get a whole lot worse before it got better), this was not a welcome import in conservative eyes. (This all happened around 1922 and, if you’d asked someone in a Tokyo street prior to that date about ‘karate’, they’d say they’d never heard of it, it only existed in the Okinawan islands [2])

‘Karate’ had to have an image make-over to make it palatable. Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado, was a key mover in this area. He (and others) helped to make the necessary adjustments and secure karate in Japan as something the establishment would welcome.

Otsuka Hironori Sensei managed to eventually unshackle himself from the Okinawan karate system that he had previously been so eager to embrace (whether by accident, fortune or design is open to speculation) and from that base and his martial cultural roots in Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, he was able to craft something new, something distinctive, and was entirely happy to describe it as ‘Japanese Budo’ (while still holding on to the ‘karate’ moniker).

Ducks and Zebras.

‘If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck and looks like a duck…it’s a duck’. Take a quick look at the qualities that the casual observer would see in Wado karate, a kind of comparative checklist; what is it you find in most styles of karate?

- An emphasis on punching, kicking and striking; which lends itself well to a sport format.

- A training regime which includes solo kata, which all follow a similar external structure and hold on to original names which define their Okinawan origins.

- A training uniform that would not be out of place in any karate Dojo in any style in the world.

Bear with me on this one; the saying, ‘When you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras’. This is told to trainee doctors, reminding them to think when diagnosing, of the most common, hence the most obvious answer. But I recently heard a doctor explaining how this idea was of limited use and how she had once misdiagnosed a patient suffering from a rare condition. Is Wado perhaps the zebra?

Take another look at the above checklist; all but the second point can be explained away; firstly, striking and kicking are not unique to karate. Secondly, it was Otsuka who was one of the main movers in pushing towards a sport format [3]. And thirdly; the uniform (Keikogi) was just a convenient design development that happened over decades, which was inevitable really.

Point 2 has been chewed over a lot by karate people, both Wado and non-Wado, but I will offer my view in a nutshell. Otsuka saw something in the karate kata that he could use. What he wanted was a framework, no need to reinvent the wheel. What was really clever was that he transposed his own ideas on top of that framework, which, interestingly, was hugely at odds with how the other karate schools/styles used it.

Wado as Jujutsu.

Why would that even be considered?

Evidence?

The second grandmaster of Wado Ryu Otsuka Hironori II at some point decided to re-register the name of his school with the authorities (probably the Dai Nippon Butokukai) and call it ‘Wado Ryu Jujutsu Kempo’. So ‘karate’ was dropped completely and ‘Jujutsu’ was added. I am not going to second guess or explain the reason for this, I am not Japanese and I am not versed in the Japanese martial arts political world, but I will speculatively introduce a few thoughts from a very western perspective (always dangerous).

Firstly, apply a similar checklist to the one above, but for Jujutsu, and, from a casual lazy western perspective, nothing stacks up.

The first grandmaster and creator did indeed add a catalogue of standard Judo/Jujutsu techniques to the original list he had to present to the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938, but these were largely dropped (the exceptions being the Idori and the Tanto Dori). But, my observations tell me that it would be a mistake to assume that this is all there is to traditional Japanese Jujutsu, the complexity goes much further than Jujutsu tricks [4].

What about the word ‘Kempo’ (or ‘Kenpo’). Actually, this has a long history in Japanese martial arts.

The term Jujutsu did not really exist as a distinct entity in Japan until the early 17th century, before that a whole bunch of other terms were used; kumiuchi, yawara, taijutsu, kogusoku and kempo. ‘Kempo’ is just the Japanese version of the Chinese Chuan Fa, or ‘Fist Way’. This does not mean that Kempo is from Chinese boxing, that is a rabbit hole not worth going down. There is however a strong link with the striking aspect of Old School Japanese martial traditions, often associated with Atemi Waza, the art of attacking anatomical weak points with both hand and foot. There is a suggestion that Otsuka Sensei was really skilled at this prior to his first exposure to Okinawan karate and that his first Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu teacher, Nakayama Tatsusaburo was somewhat of on an expert in this field.

A conversation with someone closer to the source also suggested that the word ‘Kempo’ had been around earlier in the history of the formulation of the distinct identity of Wado, but I have been unable to verify this with documented evidence.

All of this tips the scales in favour of the inclusion of the word ‘Kempo’, but, this is just my opinion, there has to be more to it than that, there always is.

One more piece of evidence to muddy the water.

When master Otsuka had to register his school with the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938 he officially recognised one Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki the semi-mythical founder of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu as the founder of Wado Ryu, rather than himself. This might not be as unusual or controversial as it sounds. Firstly, there is the Okinawan/Japanese problem, so this is a smart political way of painting Wado in the right colour to be accepted in the highly conservative establishment of the Butokukai. But, Otsuka Sensei himself explained this point; saying that, because the actual ‘founder’ of karate was unknown, his best option was to name Akiyama. [5] The suggestion being, I suppose, that the Yoshin Ryu (SYR) component of Otsuka’s new synthesis was significant enough to make this entirely permissible.

There is also an historical precedent, well in theory anyway, this is to do with one of the early branches of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, not so very far removed from Otsuka Sensei’s root art of Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu.

In the 1700’s one Oi Senbei Hirotomi seems to have picked up the reins of what was established as ‘Aikiyama Yoshin Ryu’; a theory goes that in his efforts to claim a direct lineage for his curriculum he also used the Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki name in a more blatant way than just applying it to the signboard of his school, he used his name as official founder. This may have been to deflect attention away from any thoughts that his own teachings were a blend of other influences by actually saying that Akiyama was the real founder of the Ryu not Oi Senbei! Was this done out of modesty or deception? Was it even true? Who knows. It is one those mysteries that will never be answered.

Ellis Amdur puts other theories forward, suggesting that by placing a semi-mythical person as figurehead you create space to allow your new development/style/school to stand on its own feet and to become established without the glare of unnecessary criticism or accusations of immodesty. Is this perhaps in part, what Otsuka Sensei was doing. [6]

In conclusion, just what is Wado? New species, sub species, synthesis or something that defies categorisation? And, the final question; does it even matter?

Tim Shaw

[1] Tasmanian Tiger (extinct 1936), it looks like a skinny wolf, but it has stripes down its back like a tiger; in fact it was a kind of carnivorous marsupial.

[2] If you said ‘Kempo’ you might get a glimmer of recognition.

[3] Wado wants to play in the ‘sport/competition’ sandpit? Call it ‘karate’ and the door opens, it’s all very clever politically.

[4] At the time many of the listed techniques were common knowledge, even to schoolchildren, but that doesn’t make them any less difficult.

[5] Source; ‘Karate Wadoryu – from Japan to the West’ Ben Pollock 2020. An excellent resource. Who in turn drew his reference from, ‘Karate-Do Volume 1’ Hironori Otsuka 1970.

[6] Source ‘Old School’ Ellis Amdur and further commentary from Mr Amdur at https://kogenbudo.org/how-many-generations-does-it-take-to-create-a-ryuha/

Books for martial artists. Part 2. East meets West, and West meets itself.

In this second part I want to dip a toe into the way ideas originating in the far eastern martial arts migrated to the west and then morphed into something else.

Also, whether the current brands of ‘self-help’ publications may or may not have something to offer us as martial artists.

Sun Tzu – The Art of War.

If anything can be clearly categorised as being a ‘martial arts’ book it has to be Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Said to have been written around 500 BCE, this short text contains a wealth of martial knowledge and strategy. [1] The beauty of the book is that it is broad in its application and scope, yet detailed enough to pick out examples for reflection; and it plays with the conceit of being applicable to individual combat and battles involving large numbers.

People in the west have been aware of this book for as long as there has been an interest in orientalism, and inevitably it has been appropriated by the business world. So many spin-offs telling us how Sun Tzu’s book can be applied to the cut and thrust of the high-powered boardroom -everyone is looking for an edge. Titles appeared like, ‘Art of War for Executives’, ‘Sun Tzu – Strategies for Marketing’, etc, etc.

Musashi Miyamoto – ‘The Book of Five Rings’.

Musashi’s terse book on strategy and fighting suffered a similar fate to Sun Tzu. I have mixed feelings about the Book of Five Rings. At least one Japanese Sensei I have spoken to has been puzzled about Musashi’s status, as in, ‘why this guy?’, ‘Why does this dubious character deserve so much attention, when there are so many more elevated examples… Katsu Kaishu was an amazing model, yet nobody talks about him?’.

I have seen ‘the entrepreneurs guide to the Book of Five Rings’ and others have tried to piggyback on this book of ‘wisdom’.

Musashi was a product of his age, and in terms of Darwinian principles, managed to stay alive through sheer cunning and an unorthodox approach (though, what was orthodoxy in that age is very fluid. 16th century Japan was like the wild west). Again, you have to understand the context.

A quick note on the ‘Warrior’ mentality.

Excuse me for my cynicism here but nothing grinds my gears like the overuse and appropriation of the word ‘warrior’.

As a ‘meme’ on the Internet all these ‘warrior quotes’ are guaranteed to cause me to gnash my teeth in anger and frustration.

Musashi ‘quotes’ abound (which end up as not ‘quotes’ at all, just some made up cobblers nicked from another source). [2]

Just what do people mean when they refer to ‘Warriors’ anyway? Are we talking about the modern context; the professional soldier? If so, the gulf between that model and the model presented by someone like Homer when he introduced us to Achilles and Hector, or, in Japan the stories told about Tsukahara Bokuden (1489 – 1571) [3] is just too huge a gulf to be bridged; different worlds, different mentality, different technology. Unfortunately, the romantic appeal of BEING a ‘warrior’ attracts precisely the same people who lack all the idealised and fictional attributes of so-called warriordom, a domain for fantasists and keyboard heroes. Sad, but true.

To return to books.

‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’

I know that I have mentioned in a blog post previously about Inazo Nitobe’s ‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’ book. Essentially it is a confection running an agenda, in that Nitobe wanted to build a cultural bridge between Japan and the west with a distinctly Christian bias (he was a Quaker). He created an overblown link between the romanticised ideal of medieval chivalry and an equally fictionalised picture of the ‘code of the Samurai’; as such, in a nutshell, ‘Bushido’ was a modern invention. I’m sorry, but somebody had to say it.

‘Zen in the Art of Archery’.

Although this book has been influential for some time it also suffers criticism not dissimilar to Nitobe’s book. Eugen Herrigel, wrote the book after his experiences with a Japanese Kyudo (archery) teacher, Awa Kenzo. Herrigel was teaching philosophy in Japan between 1924 to 1929, the book was published in Germany in 1948. My view is that Herrigel’s achievement in writing this very short book was that he introduced the element of spirituality linked to Japanese martial training to western thinking. Although I feel a need to offer a disclaimer here… Herrigel has taken some flak (posthumously, he died in 1955); intellectual big guns like Arthur Koestler and Gershom Scholem pointed out that in the book Herrigel was spouting ideas that came from his connections with the Nazi party.

Yamada Shoji in his book ‘Shots in the Dark’ suggests that Herrigel had got it all wrong and that the ‘Zen’ element was embroidered into the story. Yamada also tells us that conversations Herrigel had with Awa Sensei were either misunderstood or simply didn’t happen.

The title alone spawned homages to Herrigel’s book – ‘Zen and the Art of Motocycle Maintenance’ comes to mind. Also, in a previous post I mentioned ‘The Inner Game of Tennis’ by Gallwey; it was Herrigel’s book that inspired Gallwey’s thinking; so, let’s not give Eugen Herrigel too hard a time.

Western books that may be relevant.

Rick Fields books are quite interesting, one in particular. Don’t be mislead by the title (based on what I’ve said above) but ‘The Code of the Warrior – in History, Myth and Everyday Life’ is a really engaging read. Fields gives us a potted history of the urge to take up arms, from the prehistoric times through to Native American culture and even a chapter on ‘The Warrior and the Businessperson’, looking at Japanese business methods and their link to samurai mentality.

Rick Fields other books have a more spiritual dimension and tend to look dated and New Age in their outlook, (written in the 1980’s); ‘Chop Wood, Carry Water’ has a clearly Buddhist vibe with a touch of the ‘Iron John’ about it. [4]

Self Help books.

Although not specific to martial arts training the so-called ‘Self Help’ book explosion may have some useful cross-overs. I had previously written a book review for ‘The Power of Chowa – Finding Your Balance using the Japanese Wisdom of Chowa’ by Akemi Tanaka. There are other books encouraging us to lead better lives that have a base in Japanese thinking, but Tanaka’s book has a clear objective of helping people to restore a meaningful balance in their lives.

I know other martial artists I have spoken to have found certain authors useful in contributing to the spiritual side of their martial arts experience. To mention a few:

- Stephen Covey, author of ‘Seven Habits of Highly Effective People’. I haven’t read it but I did read his book, ‘Principle Centred Leadership’. My takeaway from that was how much Covey was borrowing from other sources – some stand-out examples seem to come from Taoism; but useful nevertheless.

- A raspberry from me for Richard Bandler, I am suspicious of anything from him and his followers; he is one of the originators of Neuro-linguistic programming (NLP). It is, essentially pseudoscience and latest neurological research suggests that Bandler is barking up the wrong tree.

- Following a Zenic direction, Eckhart Tolle’s descriptions of the benefits of ‘living in the Now’ are worth taking a look at (though avoid the audiobook version of ‘The Power of Now’, unless you suffer from insomnia; his voice is one continuous flat drone).

- Followers of this blog will perhaps have realised that I have a lot of time for Jordan B. Peterson; however, only three books have been published [5], but the online lectures are solid gold. Peterson has some interesting thoughts on serious martial artists, who he talks about in his references to the Jungian concept of the Shadow.

The Dark Arts.

This post would not be complete without mentioning what I have called ‘the Dark Arts’. These are almost exclusively western in origin. I am not really sure where I stand on the efficacy or even the morality of these publications, but here is a list:

- ‘The Prince’, Niccolo Machiavelli 1532. The vulpine nature of Machiavelli just oozes off every page. He was a master of deception and treachery, a minor diplomat in the Florentine Republic. ‘The Prince’ is a masterwork for anyone who wants to succeed at any cost. But you might want to wash your hands afterwards.

- ‘The Art of Worldly Wisdom’ Baltasar Gracian 1647. Similar in nature to ‘The Prince’. Gracian was a Spanish Jesuit priest. Winston Churchill was said to be inspired by this book. It is dedicated to the arts of ingratiation, deception and the cunning climb to power. Just as apt today as it was then.

- Contemporary writer Robert Greene is perhaps the inheritor of Machiavelli and Gracian; in fact, he borrows heavily and unashamedly from these sources. He initially shot to fame with his 1998 book ‘The 48 Laws of Power’. The titles of his books always suggest to me as a mandate for roguery and look to all intent and purposes like a villain’s charter, as an example; ‘The Art of Seduction’ 2001 and ‘The Laws of Human Nature’ 2018. This put me off, that, and a conversation with my barber who seemed to enjoy the salacious nature of Greene’s ‘words of wisdom’. But I listened to Greene interviewed on a podcast and my view changed. Having now read ‘The 48 Laws of Power’ I realised that Greene wrote this almost from a victim’s perspective and I saw in it mistakes I had made in my past and have since bitterly regretted. A useful and humbling experience. There is more humanity in this book than I initially assumed – but also a good measure of naked ambition and dirty dealings, if you like that sort of thing.

Clearly this is not a comprehensive list of everything out there, just things I wanted to share. I think there are many martial arts people who want to look beyond the physicality of their discipline and have an urge to find a wider meaning to their efforts – which is entirely in line with the broader scope of Budo, as envisioned by Japanese masters like Otsuka Hironori, Kano Jigoro and Ueshiba Morihei.

Follow your curiosity and enjoy your reading.

Tim Shaw

[1] The Penguin ‘Great Ideas’ edition is a mere 100 pages in length, with each page consisting of very short stanzas – a very simple read.

[2] The only time I felt inclined to use a ‘warrior based’ quote was a very apt one that I quite liked, “The nation that will insist on drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking done by cowards”. Thucydides.

[3] Bruce Lee’s ‘Fighting without fighting’ scene in ‘Enter the Dragon’ was stolen straight from stories about Tsukahara Bokuden.

[4] ‘Iron John – A Book About Men’ by Robert Bly. The author attempted to rescue the soul of masculinity, this was intended as an antidote to the excesses of feminism (well this was 1990!) but it was ridiculed and derided in all quarters as it became associated with all the ‘sweat lodge’, ‘male bonding’ razzamatazz, that might have been quite benign, although misguided, but quickly turned into something darker.

[5]. Jordan B. Peterson books; ‘Maps and Meaning’ (a demanding read), ‘Twelve Rules for Life’, (much easier to read and really relevant) and the latest book, ‘Beyond Order’, also good.

Image: ‘St Jerome in his study’ by Albrecht Dürer 1514. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Books for martial artists. Part 1. Lost in translation.

A two-part martial arts journey into where ‘extra reading’ can take you.

It’s only natural for us to want to boost our martial arts learning by reading around the subject, or tracking down published material that in some way gives us hints as to how to focus and direct our lives in a manner worthy of the Budo ideal.

In a previous blog post (‘Why are there so few books on Wado karate?’) I was puzzling over the fact that there are very few written sources specifically dedicated to Wado. But what about the general reader who might want to dig into history, culture or how things operate in other systems?

Publications originating in the far east.

Like everyone else, I have found myself drawn towards written material from Japan or China, with a particular fascination with the really early stuff. But of course, I have had to make do with English translations.

However, experience has taught me to be wary of these translations, as so much can be lost or completely twisted out of shape.

Here are the main problems:

- Bad translations either written with the translator’s bias, a political agenda, the translator’s preconceived ideas, the translator looking at the text through modern lenses, the translator being a non-martial artist, thus not understanding specialised language, etc.

- Misunderstandings; e.g. kanji or old style Chinese characters being badly copied [1], or so outdated as to be almost unintelligible without HIGHLY specialised knowledge.

- Things taken out of context, e.g. their historical context, or cultural context.

- Deliberate obfuscation – text written in a way that only the initiated can understand them.

Of all of the above I think it is the ‘taken out of context’ that is the biggest error. The further back in history you go the more you encounter cultural and historical contexts that are so alien they are almost undecipherable. As a comparison, think how difficult some phrases from Shakespeare are to understand. [2]

Pictures speak louder than words.

You might imagine that pictorial references, even in antiquated texts have more to offer than translations? But that also can be hugely problematic.

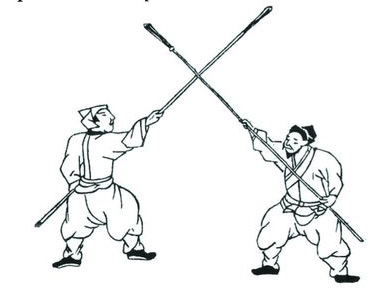

Here are two early martial arts examples that come to mind:

The Heiho Okugisho.

The earliest origin of parts of this martial arts book might go back as far as 1546, but really, who knows? Studies on this suggest it’s a chop-together of mostly Chinese sources that found their way to Japan and became really popular among martial arts enthusiasts in the Edo Period. It included, descriptions and drawings of techniques of spear and halberd, as well as empty-handed techniques and was eagerly devoured by aficionados and dilettantes alike and, according to one commentator, was passed around like porn mags or chicken soup recipes, with a hopeful belief that it was the real McCoy. But even with its enticing line drawings of men in antiquated Chinese dress, just about everything in it is bogus. Not to put too fine a point on it, it’s like a modern-day Photoshop fake. And still people studied it trying to tease out the ‘secrets’ hidden within and looking for the missing link of a Chinese connection to Japanese martial arts. [3]

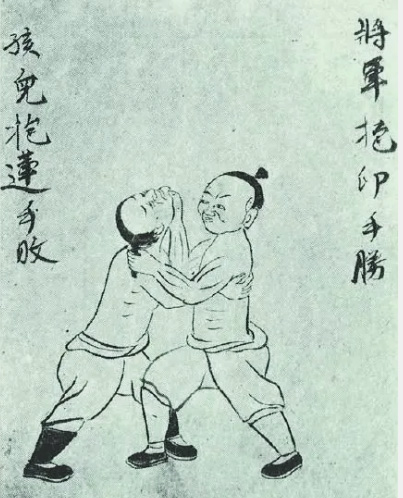

The ‘Bible of Karate – the Bubishi’.

This particular publication has a strikingly similar backstory to the Heiho Okugisho. The structure follows a comparable pattern and with the same maddening obscurities. Here is a book that was ‘kept hidden’ until around 1934 when parts of it were published in Japan. It emerged from Okinawa and so people inevitably connected it to Okinawan karate. It’s a book comprised of Chinese self-defence moves (line drawings and brief descriptions), various sections connected to herbalism and a questionable set of visual diagrams relating to ‘vital point’ striking. Much of it is written in flowery ancient Chinese characters that only the initiated have a hope of understanding.

When it was released as an English translation in 1995, I was eager to get my hands on it. Yes, it was intriguing and I studied it closely, trying to extract some kind of meaning from it. The drawings I could relate to, but any techniques I could find in them were quite basic; but really, what did I expect to find in line drawings with no meaningful accompanying text? Essentially, as a ‘how to do it manual’ it was (for me at least) a failure.

Over the last twenty-seven years more critical and well-informed eyes have examined the Bubishi and in some areas it is just not stacking up. Take for example its claim that it related to White Crane Chinese Gung Fu, and thus suggesting a clear link with Okinawan karate to a Chinese root. Apparently, according to experts in the field, White Crane has so much more to it than that, AND the ‘vital point’ diagrams look more and more like pure fantasy. [4] [5]

Here’s another one; not a book but a document:

“Itosu said…” well, did he really? And if so, what did he actually mean?

Some karate enthusiasts have eagerly brought their gaze towards an obscure, very short letter written by Okinawan karate master Itosu Anko (1832 – 1915) [6]. The letter was written to an Okinawan school board in 1902 and its intention was to explain in ten bullet points the virtues of karate training in the education system and a few basic guidelines as to how to approach training – to keep you on the right track. The letter has value by virtue of the fact it survived. In Okinawa so little was written and most of what was ended up in ashes as in 1945 the American forces had to pretty much raze large sections of the Okinawan islands to root out the resistant forces. But, as a cultural artefact Itosu’s letter is a hell of a rarity and really that is where its value comes from.

Some enthusiasts have rightly acknowledged the translation issue but have found themselves chasing after the wrong rabbit and have suggested that it is better to have a non-martial artist, non-specialist do the translation. Actually, it is that very problem that ruined Otsuka Sensei’s book for western audiences, because the English translation done by a non-martial art specialist misses out the nuances and implications of Otsuka Sensei’s carefully chosen characters.

With Itosu’s letter it is incredibly difficult to tease out anything beyond platitudes and generalisations, it’s not ‘The Da Vinci Code’ or the ‘Mayan Prophesies’, it’s a letter with a clearly defined audience in mind (the school board) and it pretty much does the job. For some people it has become a kind of manifesto, but if that is the case it is thin gruel. Yes, it is interesting, particularly as a snapshot in time and place, we can learn a lot from it as a cultural icon and there is much to gain from this window into a world long gone.

There are too many books and publications to go into in this post but I would like to put in some recommendations that particularly chimed with me and that I am prone to go back to time and time again.

- ‘The Unfettered Mind’ Takuan Soho. I have always loved this book, written some time in the 1630’s by monk/scholar Takuan Soho as a series of essays directed as guidance to the famous Yagyu clan of swords masters, teachers to the Shogun. The suggestion has always been that it was a Zen text but contemporary expert William Bodiford puts a good case that it is really a Neo-Confucian work (to me it fits far better than the contemplative approach of the Zen school of thinking).

- ‘The Tengu-Geijutsu-ron’ of Chozan Shissai (translation by Reinhard Kammer, published as ‘Zen and Confucius in the Art of Swordsmanship’). Written around 1728. Shissai expresses his ideas in a novel format and has harsh words for the swordsmen of his generation. The philosophical content and mindset come to life once you realise what he means by ‘Heart’, ‘Mind’ and ‘Life Force’ as it relates to Japanese martial culture. But there are some clever models and ideas scattered throughout the text.

- ‘The Sword and the Mind’ ‘Heiho Kaden Sho’, translation by Hiroaki Sato. The core essays date from the mid 1600’s and comprise practical guidance by the above mentioned Yagyu family. A great history section, but there is considerable content on the Mind and strategic outlook for the professional swordsman.

It won’t have escaped your attention that the above examples are all from swordsmanship, but it is my feeling that Japanese Budo/Bujutsu is well represented through the refinement of the art of the sword; particularly as it relates to the high level of psychospiritual culture that developed over many centuries and probably reached its zenith in the 17th century. The relevance of this is still present in our approach to training in modern martial arts, particularly Wado; weapon or no weapon, we carry a technical legacy that should still be with us, and we should always be trying to identify and reach towards those rarefied goals.

Conclusion.

Ultimately, reading any reliable material in and around your pet subject has to be a good thing. Understanding context, in particular, is crucial to getting under the skin and really understanding what you are doing. Many systems have depth and history and have gone through refinement and transformative processes to get where they are today. Generally speaking, reading is one of the most sure-fire ways of journeying into the cultural lineage of your system.

My view is that reading gives you glimpses of a mindset that is so very different from our own, whether it is the Itosu Letter or master Otsuka’s terse poetic axioms [7] it is clear that the time, the place and the culture inevitably wired-in ways of thinking and looking at the world that have entirely different priorities to the ones we have today. Yes, there are universal principles like justice and a desire for peace, but the societies were structured on pre-industrial almost feudal models (or were in the process of struggling to break free of those models) so it would be a mistake to simply project our views on to their writings.

In part two I intend to take a brief look at more modern examples (that may or may not be written with martial artists in mind) and look at how the west chooses to utilise eastern examples.

Tim Shaw

[1] Early text were hand copied, often generation after generation, remember, printing presses only worked well with European alphabets. Errors occurred, and then were magnified (Chinese Whispers).

[2] I have a particular fascination with the I-Ching, (said to be over 5000 years old). On my bookshelves I have five versions which I tend to compare against each other, the differences are quite startling.

[3] Reference; Ellis Amdur, ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’.

[4] See, https://whitecranegongfu.wordpress.com/2014/12/02/the-bubishi-myth/

[5] Consider the story of how Doshin So the founder of Shorinji Kempo was inspired to create his system after observing a mural painted on the wall of the Shaolin Temple, when he visited in the 1920’s and 30’s, showing Chinese and Indian monks training together. Although Shorinji Kempo history states that it was actually the spirit of training together that inspired Doshin So, not necessarily the technique. But it goes to show how pictorial imagery can inspire ideas.

[6] Itosu Anko is a very important figure in the more recent story of Okinawan karate and features at the point just before karate jumped from the islands to mainland Japan in the form of Itosu’s student Funakoshi Gichin, who was incidentally the first karate teacher of Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado Ryu. So, in some ways Itosu can be seen as the ‘grandfather’ of the Okinawan karate element contained within Wado.

[7] Master Otsuka composed short poems to express his ideas of how martial arts should function in the world. An example, “On the martial path simple brutality is not a consideration, seek rather an intense pursuit of the way that describes peace”. Source, article by Dave Lowry, ‘A Ryu by any other name’. Black Belt magazine, May 1986.

Bubishi Image credit: ‘Sepai no Kenkyu’ Mabuni Kenwa.

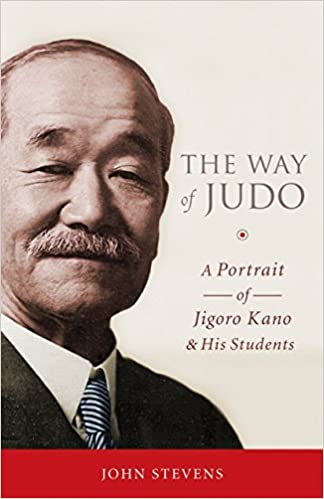

Book Review – ‘The Way of Judo, a Portrait of Jigoro Kano and his Students’ John Stevens.

A biography of the founder of Judo and what his life tells us about Japanese martial arts and modernisation.

You might ask what a book about the originator of Japanese Judo is doing appearing on a blog about Wado karate? To explain this, I don’t think it’s too bold a statement to say that Kano Jigoro was instrumental in creating the martial arts eco-culture that the founder of Wado Ryu, Otsuka Hironori, was brought up in. Kano was a moderniser and an iconoclast and so was Otsuka, although Kano was senior to Otsuka by nearly thirty years. Otsuka may have known of Kano but I doubt there was any close connection (Kano died in 1938, the same year that Otsuka founded Wado Ryu as a separate entity – Otsuka lived on until 1982). I will put forward a few observations and speculations about master Otsuka later.

The book itself.

There were so many things about John Stevens biography of Kano that surprised me. I already knew that he was the early model for Japanese modernisation and instrumental in the survival of the cultural legacy of the Old School Japanese Jujutsu, albeit packaged into a new form (how successful he was is too big a subject to go into here), but there was so much more to the man.

Here are some intriguing facts about Kano (to me anyway):

- Kano came from the higher tiers of society, so, financially and socially he already had a leg-up the ladder. Otsuka and his good friend Konishi (1) also came from more than secure backgrounds. These advantages allowed scope for freedom and exploration, as much as Japanese society allowed at the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century. Add to that a fanatical desire to dig really deeply in their chosen field and something truly special emerges with all three men.

- Kano was a traditionalist in martial arts (jujutsu) terms, but also a moderniser who was able to get a significant number of the old school hardened jujutsu masters on-board to synthesise their teachings into modern judo… how was he able to do that?

- Kano suffered considerable set-backs as he struggled to formulate, promote and develop Kodokan Judo, however, his tenacity seemed almost super-human. Clearly the man had charisma and amazing persuasive powers, and, in the early days, led from the front – he could walk the walk!

- Amazingly, he looked towards western culture to find models that would work for the Japanese people. He admired the philosophical ideas behind western physical education but hated the modern concept of ‘sport’, which to him trivialised and subverted the purer objectives of the physical culture of the martial arts (ironic when you think of his legacy today). Interestingly, it was open contests that boosted the status of Kodokan judo in the early days (2). A real shock to me was that although Kano was actively involved in the Olympic movement (particularly the failed bid for the 1940 Olympic games in Tokyo) he was actually reluctant to suggest that judo should be included, for fear that the appetite for medals and glory would be the opposite of how he saw the reality of judo.

- Stevens says that in technical judo Kano was not a fan of groundwork, but understood it as a necessity if he was to make his point. For Kano it was 70% stand-up and 30% groundwork, Stevens quotes a saying, “To learn throwing techniques well, it takes three years; to learn effective groundwork, it takes three months”. (Stevens does not give the origin of the quote).

- It seems clear that even within his own lifetime Kano’s judo was being subverted into something he was desperate to avoid. Everything that he frowned upon in modern sporting culture was acting as a magnet to the coaches and youngsters they taught. Kano was clear in his mind what the model for judo should be and he explained it in language of high ideals, but perhaps these ideals were too abstract and contradicted where the world was actually going? Kano was swimming against the tide.

- In his working life Kano was a model professional educator. His whole career was in education, he genuinely cared about people. As a scholar and a life-long learner he was a wonderful example of an insatiable and a genuine polymath. E.g. it is known that he wrote all his early training notes in English to keep them secret from his fellow trainees. What also surprised me was that Kano is considered the father of music education in Japanese schools, being instrumental in making music compulsory for all middle and high school students.

- He was without a doubt a rebellious figure, in that he kicked back against Japanese conservative views on education and he resisted the militarisation and appropriation of Japanese martial arts to fuel war and expansionism. This would have surely ruffled a few feathers at the time. Some of his political contemporaries were actually assassinated for holding opinions similar to his.

- His successes came at a price, in that he acted as a lodestone for various martial arts crazies, obsessives and prodigies (positive and negative). Too many to choose from, but to name two; Saigo Shiro and Mifune Kyuzo (3).

- Kano died at the age of 77 on board ship on his way back to Japan. It’s just my opinion but I suspect he was just burnt out.

Otsuka Hironori and Judo.

I think it is important to explain that the terms ‘Jujutsu’ and ‘Judo’ were loose descriptions that had been interchangeable for a long time, even before Kano’s ‘ownership’ of the term as a handle for Kodokan Judo.

Regarding Otsuka Sensei; even before he reached his teens Kano’s Kodokan was becoming a major force in Tokyo and beyond, how could he fail to be influenced by it?

In 1906 Kano had opened a huge 207 mat Dojo and the standard Judo Keikogi (uniform) had been established by this time. Coincidentally, one of the earliest pictures of Otskuka Ko (as he was then named) is of him in a group photo of ‘Judo’ students at middle school wearing this new keokogi, this was 1909 and he was in his late teens. While at school he was heavily involved in judo as it was evolving and working its way into the education system. He is also in the school records of 1909 as taking part in the school’s winter training and earmarked as one of the most promising judo students. (Apparently had some particularly strong throwing techniques).

In 1908 the government decreed that all middle school students should be doing either judo or kendo. We know from Otsuka family anecdotes that Otsuka Ko’s mother discouraged her son from kendo, and he had some background training from his mother’s uncle in old school jujutsu and on top of that Otsuka was to come under the influence and tutelage of Nakayama Tatsusaburo, the middle school’s hired coach, who clearly taught him judo and opened the door to him learning Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu which is largely recognised as being one of the base-arts of Wado Ryu.

In his book, ‘Karate Wadoryu – from Japan to the West’ Ben Pollock mentions that “There is the possibility Otsuka was practicing judo at the Kodokan at some point in the period prior to him starting his study of karate-jutsu”. Clearly this possibility is not beyond the bounds of credibility, it is known that Otsuka was well connected with some of the leading lights of the Kodokan, including Mifune.

Is there any surprise that Otsuka’s concocted curriculum he submitted to the Butokukai in 1939 to register the name and the style ‘Wado Ryu’ was padded out with techniques from the established judo canon? Look at it from this angle; a huge percentage of those who went through the Japanese middle school would have a pretty good idea of what those throws were, they weren’t unique to Wado, they were common techniques. In the same way if you asked an English schoolboy the basic mechanics of manoeuvres in football, he’d be able to tell you; it is part of the system and the way physical education is taught. This is not to take anything away from Otsuka, as it is known that his grappling skill was at a very high level.

But what intrigues me the most was not the technical base of the influence of judo and Kano on Wado, but the philosophical and organisational approach Otsuka later took. Did Kano’s example act as a beacon of influence for Otsuka?

Japan was breaking the traditionalist mould and Kano’s example may have showed Otsuka that this can be done, and that the climate was right.

As an example; Kano is said to have originated the basic idea of the belt system (although the many coloured belts is rumoured to have originated as a later development in Europe). The way we work today, our hierarchies, ladders of promotion, syllabus developments all relate to how things are done in the education system – some people say it is more closely related to military systems, but that argument becomes very ‘chicken and egg’. Remember, Kano was the educationalist with a vision for the whole of Japan and the wider world (hence his involvement with the Olympic movement and the ideas of Baron de Coubertin).

Wado, like other systems rejected the long-established certification system of the Koryu (Old School) Japanese martial arts and adopted another, modernised, system; Kyu/Dan ranking. It was workable, particularly as Dojo branches then became sub-branches, then regional branches, followed by national branches etc. At some stage, somebody must have thought this was the way to go. It has a certain convenience to it. Committees sprang up like mushrooms and seniors became ‘officials’ and then, I suppose ‘suits’ (4). The move towards factoryfication became inevitable, and in many of the larger Wado organisations continues today.

Personally, I don’t look at the Kano story as just something that belonged in its historical time, there are lessons and parallels to be drawn that are just as relevant today. John Stevens did an amazing job with the book and tried to strip away any hint of propaganda and in doing so presented Kano as a formidable figure, but with human flaws. It would be a huge loss for the example set by Kano to be buried in the history books.

Tim Shaw

1 Konishi Yasuhiro, 1893 – 1983 founder of Shindo Jinen Ryu karate, an early pioneer along with Otsuka. As with Otsuka Konishi started out as a traditional jujutsu practitioner, they had a lot in common.

2 The ‘contests were billed as ‘exchanges of techniques’ or ‘exhibition bouts’ and unashamedly pitched school against school; the aim was for Kodokan judo to come out on top, and many times they did. ‘Exchange’ training also happened in the early days of Wado, as Suzuki Tatsuo recounts in his autobiography. So, this was definitely part of the culture.

3. Saigo Shiro 1866 – 1922, was a prodigy of Kano’s judo and elevated the status of the art in early contests, but he was hot-headed and his bad behaviour forced Kano to expel him from the Kodokan.

Mifune Kyuzo 1883 – 1965, another prodigious talent, sometimes referred to as ‘the god of judo’ Mifune was only 5 foot 2 inches and weighed only 100 lb but he was unstoppable and took over the Kodokan after Kano’s death.

4. A phrase that came to suggest; those who no longer actively trained but their authority came from association with Otsuka Sensei way back when.

Cover photo source Amazon Link.

Martial Artists Past and Present.

What did the martial artists of the past have that we don’t have today?

I don’t think it is possible to give definitive answers to this question, but it’s worth asking the question anyway.

There are many amazing and literally unbelievable stories about martial arts masters from the past, and some of them not so very far distant from the current age. For example; is it true or even possible for Ueshiba Morihei founder of Aikido to willingly stand in front of a military firing squad at a distance of about seventy-five feet and, at the moment they pulled the trigger, some were swept off their feet and Ueshiba ended up miraculously standing behind them! And just to prove a point, he did it twice! Shioda Gozo, Aikido Sensei says he witnessed this. [1].

Some of the tales from the more distant history are just as amazing.

Even if we take these stories with an enormous pinch of salt, stripping away the propaganda and the myth building, surely, there’s no smoke without fire? Two percent of that kind of ability would be more than enough. They must have had something?

It has to be said that the background to these kinds of stories is presented to us in a landscape that is so very remote from our own.

I suppose a key question is; is it possible for someone in the modern age, living a 21st century lifestyle to achieve anything like the semi-miraculous skills of the likes of Ueshiba Morihei in Japan, or Yang Luchan (patriarch the Yang school of Tai Chi) in China. Logically, if such skills exist, it may well be possible to attain such abilities in the current age, but it is weighed down with an almost unsurmountable number of negatives.

Allow me to present a speculative list of advantages these historical superheroes may have had in their favour, and then run a few comparisons.

But there are some significant challenges; beginning with the task of imagining yourself in the cultural landscape of the far east maybe a hundred years ago or even further back. This is a tough call for Westerners, as we have to peel away our own cultural understandings and inhabit the mindset of people half a world away, existing on cultural accretions that sit upon thousands of years of history, but please bear with me.

First of all, I want to present you with a puzzle that would be a useful starting place:

The possibility of rapid development.

If we take Japanese Old School (Koryu) Budo as an example, and we understand that there existed a well-established stratum of advancement; traditionally acknowledged by the presentation of sequence of certificates and eventually ending with a certification scroll that acknowledged ‘Full Transmission’, i.e. mastery of the system. That in itself could be considered a grand statement with a massive responsibility sitting on the shoulders of the recipient, the expectations are enormous, surely?

But, researchers reveal that these scrolls of ‘full transmission’ were sometimes offered to individuals with only a couple of decades of practice! I refer anyone who doubts this to Ellis Amdur’s book ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’. You have to ask yourself, how is that even possible?

In the recent ‘Shu Ha Ri’ lectures (mentioned in my blog post ‘Budo and Morality’) old time Aikidoka George Ledyard, when talking about the abilities of modern Aikido people (comparable to Ueshiba) poured cold water on an argument often brought forward in Aikido circles that if you train long enough, eventually you will ‘get it’ (something I have also heard said in Wado). In the interview Ledyard clearly called bullshit on that argument; to paraphrase; he said that they’ve had Aikido in the USA for over fifty years and still nobody can do ‘it’! I am going to be careful here as to what constitutes ‘it’. I’m not talking about fireballs of Chi emanating from fingertips; just effortless mastery and control is enough.

So, what is so very different? Let me put a few conjectural musings before you, in no particular order.

Proliferation.

In Japan in the 19th and early 20th century a huge number of mostly young men studied some form of martial art (it became part of the school system). These arts had evolved into a commodity with a price. Previously the martial arts were the domain of the warrior class, now, because of the abolition of this same class, out of work warriors found a niche living teaching anyone who would pay. (A good example of this is found in the detailed ledgers of lessons taught and fees charged by Ueshiba’s Daito Ryu teacher Takeda Sokaku.)

There was an awful lot of it about.

As a snapshot of the time; in his key formative years (pre Wado) the founder of Wado Ryu Karate-Do, Otsuka Sensei is said to have extensively sampled the huge proliferation of Dojo within a small area of Tokyo.

I think it is fair to assume that within this system there must have been a highly competitive filtration mechanism at work and it must have been very rough and tumble. To illustrate this point you have to wonder why it was that Otsuka Sensei would consider making a living out of treating predominantly martial arts related injuries? (At one point, Otsuka believed that this was an area worthy of supplying him with an income, but his teaching successes ultimately changed his trajectory).

Sanctioned Practice.

While it is apparent that the weapon training aspect of traditional Japanese martial arts struggled to survive (Naginata as an art was kept alive by the skin of its teeth mainly through the stubbornness of a few single-minded female protagonists) the empty-handed specialisms were adopted and subsumed by the powerhouse of the developing culture of what was to become Kodokan Judo. Judo, of course had a USP of being a ‘safe’ competitive format (see my blogpost on ‘Sanitisation’) and a builder of character, very much in line with progressive ideas developing within Japan at that time.

Even before that happened martial arts were considered part of the culture, and the Japanese have always been big on their culture, with a high regard for the arts and crafts and a special place for the artisans, and, it could be argued that the martial arts teachers were ‘artisans’. It may not be what an aspiring Japanese mother of the early Meiji Era might want for her son, but it still had the potential to provide respect and some form of status.

Lifestyle.

Looking at ancestors, either ours in the west or the equivalent in the far east, and, taking into account their social constraints, aspirations, outlook, mobility and world view, their bandwidth was pretty limited, compared to ours.

Theoretically our particular ‘bandwidth’ is huge, or at least it should be. For us, it’s not just the Internet, it’s education and all manner of loftier aspirations (being told what we should aspire towards) all supported by modern mechanisms, the structural framework of the society we live in and how we are kept secure by infrastructures that protect us from harm and ensure we are healthy.

Well, that’s how it’s supposed to work, but very recently things have become, to say the least, ‘challenging’, which in a way has highlighted some of the flaws in our current system.

Research has shown that this arguably ‘widened’ bandwidth is causing an actual shortening of our attention span, resulting in us leaping from one stimulus to another; one item of clickbait, and yet more irresistible reaffirmations on social media to boost our feeling of worth. Critics say this is actually dumbing us down and even restricting our brain power [2].

In the modern age the pressures of work leave less time to pursue other activities. In terms of martial art training in the west, anyone who trains twice a week is doing well and has probably established a good balance. Three times a week and people may say you are hardcore, any more than that and you’d probably be classed as an obsessive.

But this is so incredibly lightweight compared to someone like Shotokan Sensei Kanzawa Hirokazu who’s university training included multiple training sessions in one day! Or the Uchi-Deshi; the live-in students of Ueshiba Morihei, who not only had their daily training but were sometimes woken up in the middle of the night to be tossed around the Dojo by Ueshiba Sensei.

In historical Japan discipline and dedication were parts of the fabric of society, as were the virtues of hard graft and perfection of character through whatever it was you chose to dedicate your time, or even your life to.

Physicality.

The physicality of the early martial arts protagonists came out of a different lifestyle; even more so in rural areas, they were said to have ‘farmer’s bodies’. Ueshiba was a big believer in the physical benefits of tough labouring on the land and used it as personal training. There was definitely a culture of physical conditioning in the Edo period martial artists, photographs of Judo’s Mifune Sensei as a young man show a very impressive sculptured physique. Otsuka Sensei was said to have been keen on strengthening his grip, though his attitude to knuckle conditioning was somewhat ambiguous.

And then there is the issue of diet… A traditional old style Japanese diet has got so much going for it. It doesn’t mean that they were living in a health food utopia; for example; because of certain farming practices involving the use of human waste, internal parasites were surprisingly common. However, even with that, compared to our heavy use of sugars, processed foods and dairy products, they were by and large pretty healthy.

Longevity.

This has been a particular interest of mine. To take as an example; if you look at the lifespans of senior practitioners of the arts that use as a USP their health promoting benefits, e. g. Tai Chi with associated Chi Gung, it’s not particularly impressive. I have tried to dig into this but the statistics are a nightmare, particularly when it comes to average lifespans, mainly because of a lack of reliable information and infant mortality stats messing up the metrics.

But examined broadly, it doesn’t look great. Even with extreme outliers like the miraculous Li Ching Yuen. He was a Chinese herbalist and martial artist who it is claimed was born in 1677 and only died in 1933, making him 256 years old! Look into the supposed facts around his life and it begins to appear slightly suspicious.

On more than one occasion I have heard Japanese Wado teachers mention that practices found in other named karate systems are guaranteed to shorten your life, and a cursory look at the available evidence from those systems seem to support that idea, but even that doesn’t really tell you the full story. It has been said that some Japanese Sensei who come to the west seem to suffer from the negative effects of the western diet. Similar things are actually happening inside Japan; with the import of western food trends causing medical conditions to develop that used to be rare in Japan. Obviously, something that needs more research.

The lottery that is longevity can be skewed in your favour, if you lead a lifestyle devoid of extremes, striving for moderation in all things, then you have a better chance at living to a great age, but that of course is in competition with your genetic inheritance. Aforementioned Kanazawa Hirokazu pushed his body incredibly hard as a young man, potentially inflicting much early cellular damage to his system, yet still lived to be 88 years old. Mind you, Kanazawa adapted his training later in life to be kinder to his body, and he took up Tai Chi. But maybe his whole family line were predisposed to good health and longevity?

Speculative conclusion.

There is no definitive conclusion, only speculation.

Try as I might, I struggled to find any statistics that indicated martial arts participation in the UK, never mind about world-wide. Besides, what does that even mean? What even counts as a ‘martial art’? It would be really interesting to compare it to martial arts participation in Japan in the opening years of the 20th century.

I think it’s a fair guess to assume that the preponderance of martial arts in Japan in those early days would ensure some kind of higher waterline than in the modern world (well, at least I hope so). If we take the seemingly fast-track roadway to ‘complete mastery’ in 19th and early 20th century Japan as a truism, then that surely supports the argument – they weren’t giving Menkyo Kaiden (full transmission) away with Cornflake box tops and there had to be something going on! [3]

It’s true that they didn’t have the level of information at their fingertips in those days that we do today – but surely, it’s not the information, it’s what you do with it that counts.

In the modern era we are becoming further and further detached from the generation of masters who could actually ‘do it’, and if there are people out there who are on that level then they are side-lined by popularism. I cite as a possible example, Kuroda Tetsuzan (‘Who?’ I hear you say. It is ironic that his sparse, minimalistic Wikipedia entry speaks volumes, without saying very much at all.)

I suppose it all boils down to; who in the modern age is prepared to go beyond the mere hobbyist level and dedicate time and effort into an in-depth study of the martial art, supported of course by a Sensei who really does know their stuff?

Tim Shaw

[1] ‘Invincible Warrior’ John Stevens 1997 Shambhala Publications, pages 61 to 62. Other sources (Shioda’s biography) tell the story in more detail and mention that the marksmen were armed with pistols. At a guess, this incident was pre-war, possibly in the 1930’s. Shioda inevitably questioned Ueshiba, asking him how he did it? Ueshiba’s answer was as mysterious as the acts themselves, but he seemed to suggest that he was able to slow time down. Both times, one man was swept off his feet; the first time it was the man who Ueshiba said had initiated the first shot; the second time it was the officer who gave the command.

[2] Numerous modern commentators have railed against the ‘dumbing down’ that is happening. Google, John Taylor Gatto or Andrew Keen, but there are many other examples that perhaps don’t contain political bias.

[3] I am aware that there is a political dimension to the Menkyo Kaiden, certainly as it appears in the contemporary scene, which to me makes perfect sense.

Image: Author’s own collection.

Budo and Morality.

Morality in Japanese Budo tends to be plagued with confusion and contradictions; not least of which is the concept of a warrior art used to promote peace. I am fairly sure that in this blogpost I am not going to be able untangle the knots; but perhaps I can add some new perspectives on this tricky issue.

I have to admit to wanting to write something on this theme for a long time but I have always swerved away from it; probably for the very same reason that many others seem to have avoided it.

I think that the main reason that people tend to duck discussing morality and Budo is the very same reason that people don’t feel comfortable discussing morality, full stop. Nobody is happy climbing on to anything that looks like a moral pedestal and have the spotlight shine upon them and risk looking like a hypocrite.

With me it is exactly the same, in that I don’t feel qualified or worthy enough to occupy that particular pulpit.

Introducing the subject of morality is a bit like the taboo around discussing politics and religion over the dinner table; two subjects guaranteed to spoil a good evening.

In the martial arts, I cannot think of any of the Sensei I have trained under who have been inclined to, or felt comfortable, climbing on to the moral soapbox. For the same reasons listed above.

Armenian mystic George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff (1866 – 1949) once said, “If you want to lose your Faith, make friends with a priest”. For me, that sums it up nicely.

However, I do believe that it is possible to tiptoe through that particular minefield and remain objective about morality in Budo.

In part, the reason for me writing this now is after recently viewing a series of on-line discussions with eminent Western traditional martial artists and, although their main theme was ‘Shu Ha Ri’, they often strayed into the thorny area of morality within Budo and the development of ‘moral character’. If you have six hours spare you can follow the link below.

It is said that in traditional Japanese Budo the Morality rules are literally woven into the fabric. I use as an example the traditional divided skirt, the Hakama. This garment has seven pleats, with each one said to represent the ’Virtues’ sought within Budo, these are the guiding moral principles. Some people say there are seven, others say five, but for convenience I will stick with the seven model. These seven are:

- Yuki – Courage.

- Jin – Humanity.

- Gi – Justice or Righteousness.

- Rei – Etiquette or Courtesy.

- Makoto – Sincerity or Honesty.

- Chugi – Loyalty.

- Meiyo – Honour.

These are described as ‘Virtues’ rather than as components of a moral code. The word Virtue is a better fit because in the west the concept of being moral tends to lead you in a slightly different direction than the Japanese model. Being ‘moral’ in the West has too much baggage, a hint of the fluffy bunny feeling about it. Either that or it is associated with po-faced condemnatory Victorianism.

Rather, the suggestion here is a person of ‘Virtue’ or with ‘Virtues’, or, alternatively, ‘Qualities’, but these must be positive qualities.

But there are a number of things within the traditional list of Budo virtues that don’t translate well. There are two main reasons for this.

Firstly, because the translations, like the Kanji, are multifaceted and have to fit into a Japanese cultural and linguistic framework.

Secondly; these martial arts virtues are the product of an Edo Period mindset, or even further back. Clearly the social structures and the mental landscapes of warriors in that particular place and at that particular time are far removed from the way we live today.

Even the translation of what would seem a fairly self-explanatory concept offers up some questions.

I will address one example, not directly mentioned in the above list, but certainly connected to it. (and this is a person reflection):

From my experience, nobody under fifty years of age ever seems to use the word ‘honour’ anymore, let alone adhere deliberately to the concept. ‘honour’ only sees the light of day in the most negative of circumstances, as an example, the concept of ‘honour killings’, how did that happen?

In much the same way as, in today’s social interactions, no man is ever referred to as being a ‘gentleman’. Similarly, across the genders. I cite as an example this observation: For many years I worked as a teacher in a Catholic girls school, and it always amused me when I saw young girls being chided by female teachers for ‘un-ladylike behaviour’, what does that even mean today? I suppose you could talk about the same behaviour as being ‘undignified’, but even that word has worn a little thin these days. (I refer you to the justifications given by St. Miley of Cyrus for the contentious ‘Wrecking Ball’ video, of which I have only heard about, of course.)

I am old enough to remember when two ‘gentlemen’ shook hands over a deal it was this symbolic act and their ‘honour’ that sealed it. It all seems to have disappeared from the world of commerce and is only seen on the sports field.

Another example from the modern lexicon is the word ‘respect’, which seems to have been warped and weaponised and is permissible to function as a one-way street. This is particularly noticeable in urban slang.

But to return to the above listed Japanese Virtues.

‘Jin’ as ‘Humanity, also has a very nuanced meaning in Japan.

Yes, it does refer to the ideals of a care and consideration of other humans beyond yourself, but also ‘Jin’ is a model of humanity perfected; we all aspire to be ‘Jin’, or at least we should be. From my observation the Japanese concept of humanity is similar to Nietzsche’s model in ‘Thus Spake Zarathustra’; of Man suspended on a tightrope caught between his animalistic nature and his God-like Divine potential. ‘Jin’ is that Divine Potential realised. It is Man perfectly positioned in the universe as the sole conduit between Heaven (the universe) and Earth. It is the triad of ‘Ten, Chi, Jin’.

For convenience sake, Morals, Virtues and Values can all be tied together into one bundle.

Regarding Values; there has been a relatively recent push towards looking for values shared across cultures; values for the whole of humanity. As we work towards an idealised global community this was considered a goal worth striving for. But it’s not as easy as it looks.

The dominance of Judeo-Christian culture and ideals over the last 1000 years has pretty much set the standards for what we understand as moral behaviour (and values) and has achieved a world-wide monopoly on what is acceptable and desirable. But we have to remember that Judeo-Christian culture is the new boy on the block.

Other cultures had been hammering out their moral codes for thousands of years before Judeo-Christian models appeared on the scene, and it is quite often at variance to what we would now deem acceptable. As an example; activities condoned in ancient Greece and Rome would cause shrieks of horror in modern Western society.

Further east, Chinese culture was blossoming when we in Europe were hitting each other over the head with sticks. Chuang Tzu in 200 BCE was wrestling with advanced philosophical problems of human consciousness (See, ‘The Butterfly Dream’) and the Han Chinese at the same period had advanced tax systems, hydraulics and machines with belt drives; while at the same time in Britain we were embroiled in Iron Age tribal brutality and cattle stealing, and then along came Christianity and everything was alright! (Sarcasm alert).

Morality still has an important role to play in contemporary martial arts, even though the world has moved on and the fabric of society has changed and continues to do so at a terrifying rate. The nature of martial arts study in the modern age inevitably involves people and wherever human interaction occurs we are better working towards common goals for the improvement of society. We are living examples of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts.

How about a campaign to restore the word ‘Honour’ and claim back the word ‘Respect’?

Respect to you all.

Tim Shaw

Featured image: Author’s own collection.

Smoke and Mirrors.

It is said that magic ceases to be magic once it is explained; although the late fantasy author Terry Pratchett contradicted this with, “It doesn’t stop being magic just because you know how it works.” I think I know what he means.

At an objective and scientific level this is the difference between the ‘natural’ and the ‘supernatural’.

Martial art skills often appear to be supernatural, where the masters are in possession of abilities that seem to be out of reach for the average person in the street; this is part of the mystique, a million fantasies have been built on this idea.

However, there are times when refined and developed technique seems to confound the mind and contradict the physical world, whether it’s Bruce Lee’s one-inch punch or Aikido’s ‘unbendable arm’ (See my previous blog post ‘On Things ‘Chi’ and ‘Ki’’).

Without allowing myself to be diverted, there has been some quiet rumblings about the more subtle aspects of Wado technique and, for the cognoscenti, a suggestion perhaps that there is more going on under the hood than the recent Gendai Budo incarnations seem to imply. And, as such, I want to shine a light into an obscure oddity that may have a peripheral connection to aspects of Wado technique (as I understand them), via a tortuous route – please bear with me.

I have been sitting on this for quite some time and thought I would share it with you*. It may be nothing, it may be something. It may even be an excellent illustration of the human capacity for boundless curiosity, and what can come out of it. You can make your own mind up.

Lulu Hurst was to all intents and purposes, outwardly an unremarkable young woman, born in Polk County, Georgia USA in 1869, daughter of a Baptist preacher, but overnight, as a teenager, she became a high earning freakish phenomenon who confounded the paying public with her jaw-dropping feats.

Dubbed ‘The Georgia Wonder’ she performed impossible acts of human strength. When asked where her skills came from the slightly built Lulu said they came as a result of her being caught in an electric storm, she was a supernatural human miracle. Even the great Harry Houdini was initially puzzled as to where this phenomenal strength came from.

Lulu was able to take the weight and strength of a number of men, often through a chair or a staff, and with only a light touch displace the resisting men. She was often completely immovable, no matter how much pressure was applied. When I first heard this story it started ring bells with me; where had I come across similar phenomena?

And then I recalled stories, anecdotes of comparable abilities being demonstrated by the founder of Aikido Ueshiba Morihei. He would hold out a Jo and ask his students to try and move it – sounds easy, but try as they might they couldn’t shift it. No explanations were given, or if they were, they were shrouded in mystical obfuscation.

Over time more of these unexplainable phenomena appeared on my radar – even with the possibility of conscious or unconscious compliance it seemed that there was something there.

But Lulu retired after only two years; she’d made her money and at the tender age of sixteen she ran off and married her manager.

Years later Lulu admitted what she had really been up to; which in my mind was no less of a wonder, but certainly there was no magical ‘electrical storm’, something much more ‘grounded’ was at work.

She finally confessed it all in her autobiography. It wasn’t the product of some great revelation; she just came across it by accident.

Her first realisation was when she held a billiard cue horizontally in front of her at chest height and invited someone to push with all their might, to try and knock her over; they couldn’t! She developed it to such a degree that a whole bunch of hefty guys could push on it and STILL couldn’t dislodge her! Then she really got into showmanship, and performed the same trick standing on one leg!

From this beginning she developed a whole array of ‘tests of strength’. What is surprising though is that initially even she didn’t know how it was done.

She was smart enough to deny the supernatural and set about studying what was really going on. The level to which she was puzzled by her own ability is illustrated by the fact that her manager/husband had asked her repeatedly to teach him how to do it, but she couldn’t, because she didn’t know herself.

Finally, she did figure it out, through studying mechanics and physics. To keep it really simple the first trick, with the billiard cue, came out of her ability to read and direct the energy of the resistance and send it into… nothing, the men were not engaging with her at all.

Houdini spotted it, but it took him a while. As the master of illusion and physical manipulation himself, it was only a matter of time.

She became more adept at these forms of manipulation, and added all of this to her act.

Does this make Lulu Hurst any less remarkable? No, not in the least.

You can read her autobiography for yourself, but be warned, it’s a slog of a read, couched in the flowery language of the time. It is called, predictably and unimaginatively; ‘Lulu Hurst (The Georgia Wonder) Writes Her Autobiography’ 1897.

To reiterate; human curiosity and the ability to explore and expand beyond the realms of what is normally accepted really does know no bounds.

Tim Shaw

*The first time I ran this idea by anyone was in communication with a now disgraced famous UK karate historian back in the 1990’s. He seemed to think I was on to something.

Photo credits:

Illustration of Lulu Hurst chair act, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 26th, 1884. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/file/11051

Black and white photographs of Lulu Hurst: credit, ‘Lulu Hurst (The Georgia Wonder) Writes Her Autobiography’ 1897. Free of restrictions on copyright.

A different take on Martial Arts Media and History.

Random reading during lock-down lead me back to a theme that had interested me for some time. In the past I had picked up a number of books on the history of the martial arts in the west. (I will give a list at the end of this post if anyone is interested).

What always intrigued me was the ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions. I was particularly interested in the civilian arts, how they were developed, how they were taught and how they were commodified.

This is a complex story but I will give a couple of examples that surprised me, and sometimes amused me.

I learned that historically the English did what the English are always prone to doing, i.e. despising the foreigners and always holding themselves up as the best. If you are interested read up on George Silver, whose book ‘Paradoxes of Defence’ written in 1599 took a swipe at the cowardly foreigners use of the rapier to stab with the pointy end instead of the slashing action of the ‘noble’ English backsword. The Italians and the French bore the brunt of Silver’s ire and he aggressively sought to make his point stick – literally. He had a hatred for immigrant Italian fencing masters, particularly Rocco Bonetti and Vincentio Saviolo. He challenged Saviolo to a duel, but Saviolo failed to turn up, which caused George Silver to crow about his superiority to anyone who would listen.

Fast forward nearly 200 years and the fencing master is still in demand. There was a market for slick Italian and French ‘masters’. Many of them taught horsemanship and, surprisingly, dancing (thus proving an observation I made in an earlier blogpost; ‘a man who can’t dance has got no business fighting’). The demand did not come from the hoi polloi, the proles – no, it came from the aristocrats, and for good practical reasoning.