Hironori Ohtsuka

Is Wado really a style of Karate?

I am publishing this post on here as an example of the more focussed articles I have lined up for the Substack project. My postings on Substack will eventually be on two levels; free content that comes out every week and content that can be accessed by a small paid monthly subscription, believe me, it will be worth it. If you haven’t already, sign up free for the project at, https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

Btw. If you are signed up and on Gmail, be wary that it has a habit of dropping Substack posts into the ‘Promotions’ folder.

On with the theme.

Everything has to fit into some kind of category; labels must be attached and pigeonholes have to be filled – otherwise how do we know what we are describing. It is a quick way to make sense of things, particularly if we want to communicate to other people what we are talking about.

The quick shorthand operates largely because we are in a hurry – someone asks, “What do you do with your evenings?”, answer, “I go to my karate class”. The conversation could end at that point, or the questioner might ask for more information, out of politeness or maybe they are genuinely interested. And that is your opportunity to volunteer more detail.

Do we want Wado to be called ‘karate’?

But we Wado people are likely to be entirely happy to allow what we do to be identified as ‘karate’. But, is Wado Ryu/Kai etc really karate? Maybe it is something else which has not been truly pinned down, like a newly discovered genus; a wild critter that is neither ‘dog’ nor ‘cat’, a kind of Tasmanian Tiger, but still kicking around, possibly even thriving? [1]

It is entirely possible that Wado sails under a flag of convenience? I have cousins who hold both US and UK citizenship and I can’t help noticing that when they are in the UK they fly the US flag and when in the USA they fly the British flag when it suits them (really noticeable when the accents change). With Wado it very much the same; being identified as ‘karate’ has opened many doors for them, but what about its other possible identifying qualities, what are the competing factions?

Let me try and lay out the case… with some provisos, I am not Japanese and I run the risk of looking at this from a very western viewpoint, so everything here is conjecture and opinion.

Let me start with the easy one:

Wado as Japanese Budo.

This is where we apply the national pride and cultural credentials to Wado. It has such deep roots that to explain it would be like trying to untangle spaghetti. This is the bigger ‘identity’ issue. ‘But Wado was only recognised as an entity in 1938’! – I hear you say. Maybe, but, as we will see, the complexity of the history of Japan’s own indigenous martial systems is not to be taken lightly, particularly as it applies to Wado.

Personally, I quite like the ‘Wado is a distinct form of very Japanese Budo’ angle; it ties it neatly to the unquestioning high cultural and moral characteristics of anything that falls into the category ‘Budo’. But, as we know ‘Budo’ is a broad grouping and can be annoyingly difficult to pin down, especially when it uses high-minded and sometimes vague terms in which to describe itself.

But the subtext here should not be skipped over too quickly – ‘distinctly Japanese’, we are now talking about Budo as a kind of cultural artefact, one that has to be wrapped in the flag. But ‘distinct from’ what?

Historically, indigenous Japanese arts have had their heyday, and since Japan took to embracing all things western, these ‘arts’ slipped in the category of anachronisms; they were considered out of step with the direction Japan saw itself going in. For industrial Japan there was no going back, and, it has to be said, the Japanese performed economic and technical miracles; certainly, pre WW2, where things then went more than a little sideways.

Then came a time when these ancient arts needed to either be rescued from decline or completely resurrected, and, in the marketplace for oriental martial arts they had to stand up for themselves and proclaim who they were. This ‘claiming of the national identity’ came a lot earlier than most people think; it could be said that ‘karate’ was the first skirmish in a culture war that was yet to happen.

To keep this brief; Karate was from Okinawa, with very strong cultural ties to China, one of the earlier incarnations of the characters used to write ‘karate’ was actually ‘Chinese Hand’, so effectively this was an imported system and, considering the rocky historical relationship between China and Japan (which was to get a whole lot worse before it got better), this was not a welcome import in conservative eyes. (This all happened around 1922 and, if you’d asked someone in a Tokyo street prior to that date about ‘karate’, they’d say they’d never heard of it, it only existed in the Okinawan islands [2])

‘Karate’ had to have an image make-over to make it palatable. Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado, was a key mover in this area. He (and others) helped to make the necessary adjustments and secure karate in Japan as something the establishment would welcome.

Otsuka Hironori Sensei managed to eventually unshackle himself from the Okinawan karate system that he had previously been so eager to embrace (whether by accident, fortune or design is open to speculation) and from that base and his martial cultural roots in Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, he was able to craft something new, something distinctive, and was entirely happy to describe it as ‘Japanese Budo’ (while still holding on to the ‘karate’ moniker).

Ducks and Zebras.

‘If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck and looks like a duck…it’s a duck’. Take a quick look at the qualities that the casual observer would see in Wado karate, a kind of comparative checklist; what is it you find in most styles of karate?

- An emphasis on punching, kicking and striking; which lends itself well to a sport format.

- A training regime which includes solo kata, which all follow a similar external structure and hold on to original names which define their Okinawan origins.

- A training uniform that would not be out of place in any karate Dojo in any style in the world.

Bear with me on this one; the saying, ‘When you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras’. This is told to trainee doctors, reminding them to think when diagnosing, of the most common, hence the most obvious answer. But I recently heard a doctor explaining how this idea was of limited use and how she had once misdiagnosed a patient suffering from a rare condition. Is Wado perhaps the zebra?

Take another look at the above checklist; all but the second point can be explained away; firstly, striking and kicking are not unique to karate. Secondly, it was Otsuka who was one of the main movers in pushing towards a sport format [3]. And thirdly; the uniform (Keikogi) was just a convenient design development that happened over decades, which was inevitable really.

Point 2 has been chewed over a lot by karate people, both Wado and non-Wado, but I will offer my view in a nutshell. Otsuka saw something in the karate kata that he could use. What he wanted was a framework, no need to reinvent the wheel. What was really clever was that he transposed his own ideas on top of that framework, which, interestingly, was hugely at odds with how the other karate schools/styles used it.

Wado as Jujutsu.

Why would that even be considered?

Evidence?

The second grandmaster of Wado Ryu Otsuka Hironori II at some point decided to re-register the name of his school with the authorities (probably the Dai Nippon Butokukai) and call it ‘Wado Ryu Jujutsu Kempo’. So ‘karate’ was dropped completely and ‘Jujutsu’ was added. I am not going to second guess or explain the reason for this, I am not Japanese and I am not versed in the Japanese martial arts political world, but I will speculatively introduce a few thoughts from a very western perspective (always dangerous).

Firstly, apply a similar checklist to the one above, but for Jujutsu, and, from a casual lazy western perspective, nothing stacks up.

The first grandmaster and creator did indeed add a catalogue of standard Judo/Jujutsu techniques to the original list he had to present to the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938, but these were largely dropped (the exceptions being the Idori and the Tanto Dori). But, my observations tell me that it would be a mistake to assume that this is all there is to traditional Japanese Jujutsu, the complexity goes much further than Jujutsu tricks [4].

What about the word ‘Kempo’ (or ‘Kenpo’). Actually, this has a long history in Japanese martial arts.

The term Jujutsu did not really exist as a distinct entity in Japan until the early 17th century, before that a whole bunch of other terms were used; kumiuchi, yawara, taijutsu, kogusoku and kempo. ‘Kempo’ is just the Japanese version of the Chinese Chuan Fa, or ‘Fist Way’. This does not mean that Kempo is from Chinese boxing, that is a rabbit hole not worth going down. There is however a strong link with the striking aspect of Old School Japanese martial traditions, often associated with Atemi Waza, the art of attacking anatomical weak points with both hand and foot. There is a suggestion that Otsuka Sensei was really skilled at this prior to his first exposure to Okinawan karate and that his first Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu teacher, Nakayama Tatsusaburo was somewhat of on an expert in this field.

A conversation with someone closer to the source also suggested that the word ‘Kempo’ had been around earlier in the history of the formulation of the distinct identity of Wado, but I have been unable to verify this with documented evidence.

All of this tips the scales in favour of the inclusion of the word ‘Kempo’, but, this is just my opinion, there has to be more to it than that, there always is.

One more piece of evidence to muddy the water.

When master Otsuka had to register his school with the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938 he officially recognised one Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki the semi-mythical founder of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu as the founder of Wado Ryu, rather than himself. This might not be as unusual or controversial as it sounds. Firstly, there is the Okinawan/Japanese problem, so this is a smart political way of painting Wado in the right colour to be accepted in the highly conservative establishment of the Butokukai. But, Otsuka Sensei himself explained this point; saying that, because the actual ‘founder’ of karate was unknown, his best option was to name Akiyama. [5] The suggestion being, I suppose, that the Yoshin Ryu (SYR) component of Otsuka’s new synthesis was significant enough to make this entirely permissible.

There is also an historical precedent, well in theory anyway, this is to do with one of the early branches of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, not so very far removed from Otsuka Sensei’s root art of Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu.

In the 1700’s one Oi Senbei Hirotomi seems to have picked up the reins of what was established as ‘Aikiyama Yoshin Ryu’; a theory goes that in his efforts to claim a direct lineage for his curriculum he also used the Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki name in a more blatant way than just applying it to the signboard of his school, he used his name as official founder. This may have been to deflect attention away from any thoughts that his own teachings were a blend of other influences by actually saying that Akiyama was the real founder of the Ryu not Oi Senbei! Was this done out of modesty or deception? Was it even true? Who knows. It is one those mysteries that will never be answered.

Ellis Amdur puts other theories forward, suggesting that by placing a semi-mythical person as figurehead you create space to allow your new development/style/school to stand on its own feet and to become established without the glare of unnecessary criticism or accusations of immodesty. Is this perhaps in part, what Otsuka Sensei was doing. [6]

In conclusion, just what is Wado? New species, sub species, synthesis or something that defies categorisation? And, the final question; does it even matter?

Tim Shaw

[1] Tasmanian Tiger (extinct 1936), it looks like a skinny wolf, but it has stripes down its back like a tiger; in fact it was a kind of carnivorous marsupial.

[2] If you said ‘Kempo’ you might get a glimmer of recognition.

[3] Wado wants to play in the ‘sport/competition’ sandpit? Call it ‘karate’ and the door opens, it’s all very clever politically.

[4] At the time many of the listed techniques were common knowledge, even to schoolchildren, but that doesn’t make them any less difficult.

[5] Source; ‘Karate Wadoryu – from Japan to the West’ Ben Pollock 2020. An excellent resource. Who in turn drew his reference from, ‘Karate-Do Volume 1’ Hironori Otsuka 1970.

[6] Source ‘Old School’ Ellis Amdur and further commentary from Mr Amdur at https://kogenbudo.org/how-many-generations-does-it-take-to-create-a-ryuha/

Wado on Film (Anything on film!) – Part 2.

Continued from part 1. What can we possibly gain from these ‘records’ of genius? How do we read the evidence presented to us?

What are we able to judge?

To return to the martial arts (and other arts).

Observing films on YouTube or other sources; shapes and patterns can only give us so much. It’s how we process the information that counts, but usually we cannot help but to attach our own baggage to it; this can cause its own problems.

To expand: If we look at the idea of works of art; it is said that it’s all about relationships:

- The relationship of the artist to their subject – think of landscapes or portraits. The artist must engage and interpret their personalised understanding of the subject.

- The relationship of the artist to their medium – this is the practical depiction of the theme and all of the technical aspects involved. This is the means by which the message is delivered.

- The relationship with the artist through their work to their audience.

Now, extend that to master Otsuka, (whether it is on film or a demonstration in front of an audience):

- His subject is his understanding of Japanese Budo.

- His medium is his performance – what he chooses to show is through the prism of his selected material, be that solo or paired kata or fundamentals.

- Then, ultimately, the connection/relationship between the ‘artefact’ as presented, and the viewer, the audience.

As with all of the above, clearly, the viewer has to be up to the task.

For a viewer in an art gallery, a Joshua Reynolds portrait from 1770 may present less of an intellectual challenge than a Jackson Pollock ‘Action Painting’ from 1948. The crisp clarity of Reynolds gives the viewer more to grasp on to than the mad, seemingly random, spatter of paint that Pollock applied to his canvases. But both have amazing value and depth (to my mind anyway).

It has been said to me on more than one occasion that those demonstrations that master Otsuka did in his later life were actually designed with a particular audience in mind; for the real aficionados, for those who really had the eyes to see what we mere mortals fail to see. They are not quite Jackson Pollock, this is perhaps where the metaphor is a little too far stretched, but sadly they still reside in an area above most of our pay grades.

To understand Otsuka (or Pollock) we would need to have considerable insight into the workings of the artist’s world combined with the ability to grasp the intangible.

With master Otsuka a good starting point would be to understand the world in which he lived, as well being prepared to ditch our western lenses, or at least be aware of how they colour our understanding of Japanese society and culture at that particular time. But even then, if we plunged headlong into that task, it would need to be supported by a huge amount of practical knowledge of Japanese Budo mechanics relevant to that particular stage in its development. You would be hard pressed to find anyone with those credentials.

The comparison with the visual artists and master Otsuka can also be exercised in this way: It is a sad fact that when we encounter an artist’s work in a gallery it is often in isolation; we seldom see the work as part of a continuum, instead it is a snapshot of their development at the particular time it was produced. There are very few examples in the art world where this development can be seen; the only one I can think of is the wonderful Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where it used to be possible to follow the artist’s development as a timeline; Van Gogh’s immature work looks clunky and uncultured, he’s finding his feet, he experiments with different styles (Japanese prints influenced, pointillism, etc) and then his work starts to blossom as it becomes more emotionally charged. What a pity he only worked for about ten years. My guess is that given more time he would have gone pure abstract, what a development that would have been!

What if?

To return to Nijinsky (from part 1) – what if a piece of film was discovered of Nijinsky dancing? What would a modern ballet dancer be able to gain; how would they judge it? Perhaps Nijinsky’s famous ‘gravity defying’ leaps would not look so impressive, in fact, compared to contemporary dancers he might look very ordinary. We will never know.

(Perhaps someone might comment that he has his hand out of position, or that he is looking in the wrong direction?)

But maybe the real power is in the myth of Nijinsky as another form of truth, which allows Nijinsky to become an inspiration, a talisman for modern dancers. [1]

For master Otsuka, as suggested above, the pity would be that his whole reputation and legacy should hang on hastily made judgements of those movies shot in later life.

But who knows; if he did have film of him performing when he was in his early 40’s (say from the mid 1930’s) perhaps he would have hated to have been judged by his movements and technique at that age? I would suggest that early 40’s would have put him at his physical prime, but not necessarily at his technical prime.

It’s a bit like the way great painters would hate to be judged by their early work. [2].

Like anything that is meant to be in a state of continual evolution, its early incarnations probably served some uses, however crude, but it’s never wise to stick around. Creatives like Otsuka weren’t going to allow the grass to grow under their feet. [3]

Anecdotes of Otsuka’s early days told by those close to him inform us that his fertile creativity was a restless reality; his mind was constantly in the Dojo. The truth of this comes from his insistence that Wado was not a finished entity, how can it ever be?

Conclusion.

I’m not saying that it is a completely pointless exercise. In writing this I am still working it out in my own head, trying to remind myself that we are still fortunate to have some form of connection to Otsuka Sensei, however tenuous, and how lucky we are to still have people around who bore witness to the great teacher, although, as we know, that will slip away from us so gradually that we will hardly notice it.

I have to remind myself that we are supposed to be part of a living tradition, a continuing stream of consciousness; a true embodiment of the physical form of what Richard Dawkins called a ‘meme’ [4]. This is why instructors take their responsibilities so seriously to ensure that Wado remains a ‘living tradition’, with emphasis on the ‘living’, not an empty husk of something that ‘used to be’. This is why I am reluctant to describe master Otsuka’s image as an ‘anchor’, because an anchor, by its very nature, impedes progress.

The best we can hope for from these ghostly moving pictures from the past is that they can be seen as some kind of inspirational touchstone. But, like the shadows in Plato’s Cave it would be a mistake to take them for the real thing [5].

Tim Shaw

[1] For anyone interested in Vaslav Nijinsky I recommend Lucy Moore’s book, ‘Nijinsky’. It tells an amazing story of an amazing man in an amazing age. Why nobody has made a movie about Diaghilev, the Ballets Russes and Nijinsky I will never know. I reckon Baz Luhrmann would do a fine job if he was ever let loose on the project.

[2] I have to acknowledge that in most competitive sporting fields the athlete is probably at his/her overall prime in their more youthful days. But, when looked at in the round, karate and other forms of Japanese Budo run to a different agenda. For me, and many others, sport karate is not the end product of what we do – it’s a by-product, an additional bonus for those who choose that path.

Look at the careers of dancers. I heard it said that dancers die twice. The first time happens when by injury or by more gradual natural debilitation they have to stop doing the one thing they love, thrive on and that their whole identity has been wrapped up in. The second time, is obvious. As this BBC article (and link to radio documentary) explains: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/1fkwdll6ZscvQtHMz4HCYYr/why-do-dancers-die-twice

[3] I know that am rather too fond of making references to jazz musician Miles Davis, but I have a memory of reports of Miles refusing to play music from his iconic ‘Kind of Blue’ album in his later years; he would say, ‘Man, those days are gone’ underlining his forever onwards trajectory – just as it should be.

[4] ‘Meme’ NOT the Internet’s interpretation of the word but, like a gene. However, instead of being biological, it refers to traditions passed down through cultural ideas, practices and symbols. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meme

[5] ‘Plato’s Cave’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allegory_of_the_cave

Otsuka picture source: http://www.dojoupdate.com/wado-ryu-karate/master-hironori-otsuka/

A Few Notes on Nagashizuki.

Otsuka Sensei performing Tobikomizuki.

Without a doubt nagashizuki is a hallmark technique of Wado karate; it is also one of the most difficult to teach.

In other styles of karate I have only ever seen techniques that hint at an application that could loosely fall into the area of nagashizuki, with a very rudimentary nod towards something that could be categorised as Taisabaki, but at risk of contradiction nagashizuki in karate is pretty much unique to Wado.

But there is so much to say about nagashizuki as it features in the Wado curriculum as it helps to define what we do.

If you were to explain nagashizuki to another martial artist who has no knowledge of Wado, you could describe it as being very much characteristic of Wado as a style; a technique pared to the bone, without any frills or extra movements. Done properly it is like being on the knife-edge, it is brinksmanship taken to the extreme. I have heard a much used phrase that to my mind gives a picture of the character of nagashizuki, as follows:

‘If he cuts my cloth I cut his skin. If he cuts my skin I cut his bone’.*

Here is a technique that flirts with danger and requires a single-minded, razor sharp commitment, with serious consequences at stake.

Technically, there are so many things that can go wrong with this technique at so many levels. In an active scenario you have to have supreme courage to plunge directly into the line of fire, the timing is devastating if you get it right. Many years ago it was my go-to technique when fighting people outside of Wado, particularly those who took an aggressive line of attack hoping to drive forward and keep you in defensive mode. But I also found out that this technique had added extras, which you must be aware of if you use it in fighting; one of which is the devastating effect of the strike angle.

On two occasions I can think of, to my shame, I knocked opponents unconscious with nagashizuki. When delivered at jodan level the strike comes in from low down, almost underneath the opponent and its angle is such that it will connect with the underneath and side of the jaw. As I found out, it doesn’t need much force to deliver a shockwave to the brain, and, if the opponent is storming in, they supply a significant amount of the impact themselves – they run onto it.

This last point about forward momentum and clashing forces illustrates one of the oddities of the way the energy is delivered through the arm. A standing punch generally has to have some form of preparatory action (chambering), depending where it is coming from; nagashizuki when taught in kihon is deliberately delivered from a ‘natural’ position, and as such the arms should just lift as directly and naturally as possible into the fulling extended punch – my favoured teaching phrase for that is, ‘like raising your arm to put on a light switch’, that’s it. The arm itself acts as a conduit for a relay of connected energy generators that channel through the skeletal and muscular system into and beyond the point of delivery.

This is where further things can go wrong; the energy can be hijacked by an over-emphasis on the arm muscles or the ‘Intent’ to punch. Don’t get me wrong, ‘Intent’ can be a good thing, but when it dominates your technique to such a degree that it becomes a hindrance this can cause all kinds of problems.

The building blocks to nagashizuki could be said to begin with junzuki, then on to junzuki-no-tsukomi and then to tobikomizuki and finally to nagashizuki. Lessons learned properly at each of those stages gives you all the information you need, but it is important to go back to those earlier lessons as well. Junzuki-no-tsukomi for its structure is the template for your nagashizuki, but not just for its static position, but how it is delivered through motion; it is an amplified version of things you learned in junzuki – it is junzuki with the volume turned up.

Nagashizuki is a good technique to pressure-test; from a straight punch (at any level) to a maegeri, even to a descending bokken; this is very useful because it emphasises the slipping/yielding side of the technique; a very determined extension of one half of the body is augmented by a very sharpened retraction of the other half, the movements feed off each other, but essentially they are One. In fact everything is One, in that wonderful Wado way. And here is the conundrum that we all have to face when doing Wado technique; you always have a huge agenda of items that make up one single technique BUT…. They all have to be done AS ONE.

Good luck

Tim Shaw

*I am reminded of a line from the 1987 movie ‘The Untouchables’, where the Sean Connery character says, “If he sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue”.

Principles.

In another posting I mentioned the importance in Wado karate of focussing on Principles. Here I am going to present another angle to maybe supply a slightly different perspective.

Principles are not techniques; they are the essence that underpins the techniques. These work like sets of universal rules that are found within the Ryu. Don’t get me wrong these are not simple; they work at different levels and in different spheres. An example would be how these Principles relate to movement. There is a hallmark way of Wado movement; something that should be instilled into all levels of practice, from Kihon and beyond. If in a Wado training environment technique is prioritised at the expense of Principles of movement then students are learning their stuff back to front. The technique will only deliver at a superficial level; the backbone of the technique is missing.

This is where I think that learning a huge catalogue of techniques in itself is of limited application, and particularly mixing and matching techniques from other systems; it may work but only to a certain level. To me personally this approach lacks ambition and has a limited shelf life.

The underpinning Principles are not modern inventions, they originate way back in in early days of Japanese Budo and were forged in a very Darwinian way. These were created and adapted at the point of a sword by men who witnessed violence and blood; these things were deadly serious, no delusion, no fantasy, instead sharp reality. Those days are gone but the Principles stretch forward into the future, but they are vulnerable and the threads can easily be broken, we ignore them at our peril. It sounds dramatic, but in a way we are the custodians of a very fragile legacy.

If we look at the life of the first Grandmaster of Wado Ryu, Ohtsuka Hironori, it could be said that he had one foot in the past and one foot in the future. There is a connection between him and the men of the sword who experienced the smell of blood, particularly his great-uncle Ebashi Chojiro who we are lead to believe experienced the reality of warfare probably in the Boshin Senso (but that needs to be confirmed by someone more knowledgeable than me.). Traditional martial arts supply a direct line into the past and their values come from concepts that underpin Japanese Budo of which Wado is part.

Principle is the key that unlocks multiple opportunities and techniques. This works surprisingly well. The human psycho-physical capability is amazingly sophisticated. I have often come across students asking about the problem of learning techniques on both sides. My reply is that personally I have had no trouble switching from one side to the other. I remember hearing about sleight of hand magicians who have to learn a piece of complex manipulation with one hand and spend hours and hours of laboriously practice (and failure) to master the trick. But if the one-handed trick was to be switched to the other hand then the learning time was dramatically decreased. This is an aspect of body memory and it is not to be underestimated, it is complex, multi-faceted and amazingly fast when compared to a more calculated thought-based approach.

Tim Shaw

‘Through a Glass Darkly’.

For more years than I would care to remember I have often wondered if what we now do today in Wado Dojos is a true reflection of what the founder Ohtsuka Hironori intended?

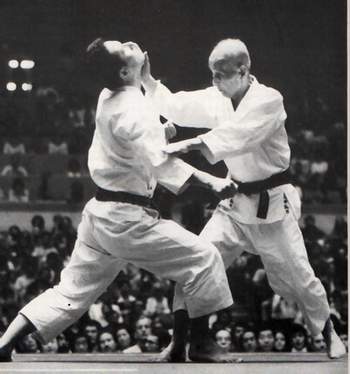

I did once see the late founder, and watched him demonstrate his art. It was Crystal Palace 1975; I was only a year into my training and competing in the UKKW Nationals. The audience waited in reverential silence as the elderly master assisted by his son gave the familiar display he always did in his later years. However, this one was different.

There was an error in the well-rehearsed display which resulted in Ohtsuka Sensei fractionally leaving his hand in the path of a descending katana blade – the result was a wound which many of us did not see, until tiny drops of blood appeared on his otherwise perfect white keikogi top. Ohtsuka Sensei seemed untroubled and carried on with the demonstration. First aid assistance was given to the old master at the end of the performance and he seemed unfazed, almost amused.

From the mid 70’s onwards I spent many hours working in the Dojo with Japanese masters all doing Wado Ryu karate. But there were differences; even contradictions.

It took a long time for me to realise that through these differences I was possibly getting a glimpse of the real Ohtsuka. It was like looking at him through a different set of lenses, with degrees of refraction and distortion.

This was frustrating in a way, a bit like trying to identify someone by their image seen through opaque bathroom glass; as I shifted my viewpoint ever so slightly the image distorted and changed. I struggled to make sense of it. But it was more complex even than that. The late master always said that Wado was a work in progress, and those with capacities and knowledge greater than mine continued to hone and refine the art; the ground was shifting and the lens was shifting as well.

Koryu martial artist Ellis Amdur said that success in the martial arts was easy…. All you had to do is pay attention! I think he is right, but I would also add a couple of things.

First you have to empty your cup; and secondly you have to be prepared to be hard on yourself and try to bypass a tendency towards observer bias, and that very human weakness described by psychologists as ‘cognitive dissonance’. Meaning; when confronted with anything that contradicts what we think we have already established we filter out the contradictions and cling to those aspects that we feel we already know. That is not really ‘paying attention’.

I learned a valuable lesson on this when acting as Uke for Ohtsuka Hironori II over ten years ago. On that occasion I experienced the full weight of his Kote Gaeshi and it came as a genuine surprise and painful shock! At the time I tried to work out what he had done and developed my own theory based on previous knowledge. It was only recently that I figured out what had really happened and how far my original theory was out – until another theory comes along anyway.

Tim Shaw