2023 Shikukai Winter Course

We invite you to join us.

11th and 12th February 2023

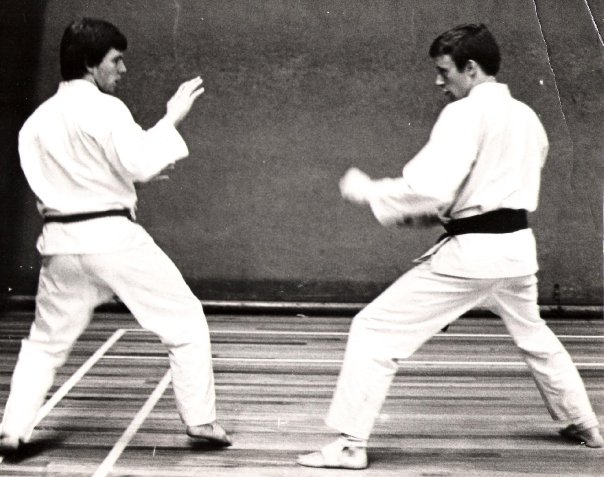

Sugasawa Sensei & Shikukai Senior Instructors

Danbury Sports Centre, Danbury CM3 4NQ

Must be booked and paid in advance

Saturday 11th Feb 11:00 Registration

11:30am – 3:00pm (3:00pm-3:30pm) personal practice

Sunday 12th February 10:30 Registration

11:00am – 2:30pm (2.30pm -3.00pm) personal practice

An additional children’s course will take place upstairs.

Kyu Gradings – Sunday after training.

Dan Grading – Sunday after Kyu grading.

Additional Dojo time

Thursday 9th – Shouwa Jyuku regular dojo session. 7.30 to 9 at Woodham Walter. £10

Friday 10th – A special session. Please bring a Tanto. 7.00 to 9 at Woodham Walter. £5

2 Day Rate

Adult member – £60

Adult Non-member – £70

Junior (11-17yrs) member – £35

Junior (11-17yrs) Non-member – £45

1 Day Rate

Adult member £35

Adult Non-member £40

Junior (11-17yrs) member £20

Junior (11-17yrs) Non-member £25

Grading Fee

Kyu Grading Fee £14.00

Dan Grading Fee £25.00

Social. We hope to have a group meal on Saturday evening in Maldon.

Martial Arts Movies.

I have avoided this one so far, but was recently tempted by a friend issuing me the challenge.

I was inclined to just supply a list of personal favourites, but I think there is more to say.

I have to start by mentioning that martial art movies, TV series, Box Sets have always been a massive let down for me. I think that why they are so much of a disappointment is because I genuinely believe that there are some amazing untold stories and narratives that have never been explored.

But, never mind the stories, what about the action? Is it actually possible to portray martial arts as it really is? Maybe with new technology and ever more adventurous camera angles it can be done, the problem is, could we wean ourselves off the overblown, exaggerated action? There is some evidence that the silly extremes have become a little passé, nobody has the appetite any more for the ‘Wire-Fu’ antics of the type seen in ‘Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon’, I think the public have called it out as too much of a stretch on their credulity.

What the public seem to want now is the crude, rough and violent approach of John Wick or Daniel Craig’s Bond in his opening salvo in ‘Casino Royale’ (that washroom scene, all those broken tiles and ceramics!) I am convinced that the fight choreographers took a huge cue from Jason Bourne, and later was to come ‘Atomic Blonde’ (Charlize Theron) with its famous ten-minute single take fight scene, that is about as rough as it can get.

By dialling it back could we perhaps reach something with more integrity without losing the drama?

I assume most people reading this have a Wado background; Wado is about as anti-drama as you could get, despite the efforts of some senior Sensei to play to the gallery; all for very good reasons I’m sure. I once asked a very senior Japanese Wado Sensei about one of the Tanto Dori he would perform as part of his regular demonstration techniques; he said he performed it in an exaggerated manner, not a ’true’ manner, so the people in the cheap seats could see what was going on. Well, in the movies there are no ‘cheap seats’, we are all up-close and personal, in fact some cinematography of fight scenes has even gone so far as to CGI rib-breaking, organ-busting x-ray images, to give the audience the closest of closest visualisation (seen in ‘Romeo must Die’ and other movies).

Audiences are much more sophisticated now. People used to think that the concentration span of the average audience member was continually shrinking, but really the trend seems to be going the opposite way; two examples; boxsets tell a story over ten episodes of an hour each and people enjoy the full depth of character and interwoven plot lines. Also, podcasts, like Joe Rogan’s, are sometimes three hours in length – they might not be consumed in one sitting but there is an appetite for it. This is where the recent Cobra Kai for me got it wrong. Clearly, they traded off the 80’s nostalgia thing (everybody is doing that now) but the plot line was basically the same that you could tell in a two hour movie, and then repeated; compare that with something like Breaking Bad and there’s a world of difference (BB is like Homer’s Iliad). Cobra Kai was like watching a loop of the typical High School teen movie – Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy wins girl back, a bit of revenge etc. etc.… and repeat.

Who needs a plot anyway?

Two words… ‘The Raid’, for me a totally enjoyable kick-ass movie with the most minimal of plot. (okay so ‘The Raid’ and the ‘Judge Dredd’ movie were filmed almost at the same time, but who cares, both of them did a good job of working the same story).

There’s more than one type of Martial Arts movie.

Let me try to construct some categories here, with some suggestions:

- Kung Fu movies, going way back. Initially for the Chinese audience and then westerners started to find them cool, with a big spike during the Kung Fu boom.

- Art House style ‘wire-fu’ movies, like ‘House of Flying Daggers’ (interestingly ‘The Matrix’ is classified as ‘wire-fu’ because of its similar use of wires, pulleys and harnesses).

- Samurai movies. Similar to the above but, for my mind, given a major Art House boost by Kurosawa. Do yourself a favour and binge on the Kurosawa classics. And his career did not end with the beginning of colour film. Later favourites, spectacular, amazing use of colour; ‘Kagemusha’ (Shadow Warrior) 1980 and ‘Ran’, King Lear in armour 1985.

- Western-based martial arts movies – It is very easy for some good movies to slip under the radar here; example ‘Red Belt’ 2008, great cast, great director David Mamet, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor, a modern and relevant movie.

- Movies where clearly the stars have martial arts skills; Recent James Bond movies, John Wick, Jason Bourne etc. More like thrillers with a lot of choreographed moves. But for me, a special shout-out for the ‘Blade’ trilogy. ‘Blade 2’ particularly, martial arts with vampires a terrific director, Guillermo del Toro, what’s not to like?

Martial Arts Novels.

This will be very short because there is absolutely nothing I can recommend, despite my best efforts. There are numerous thrillers with a loose martial arts connection – usually about ‘assassins’ which don’t really float my boat. Decades ago, I read the Eric Van Lustbader stuff and found it really lightweight.

I recently read a novel that initially got me excited, ‘The Gift of Rain’ by Tan Twang Eng, there was an element about a Japanese Aikido master, but it was never really fleshed out and the story just tried to do too much. I stayed with it till the end, but it could have been so much better.

After writing all of this I realise that I am perhaps too demanding an audience. It’s like commenting on music; so easy to talk about what you don’t like, almost impossible to persuade someone of the merits of what you do like.

Tim Shaw

Follow my developing Substack project; a weekly blogpost/newsletter published every Tuesday, with writings on martial arts, Wado karate and all things related. To support this project, please subscribe; that way I can promote all things ‘Wado’ and everything in-between. You can find this at Substack

Image credit: https://www.furiouscinema.com/ Still from ‘Invincible Armor’ 1977. Director, Dir: See Yuen Ng.

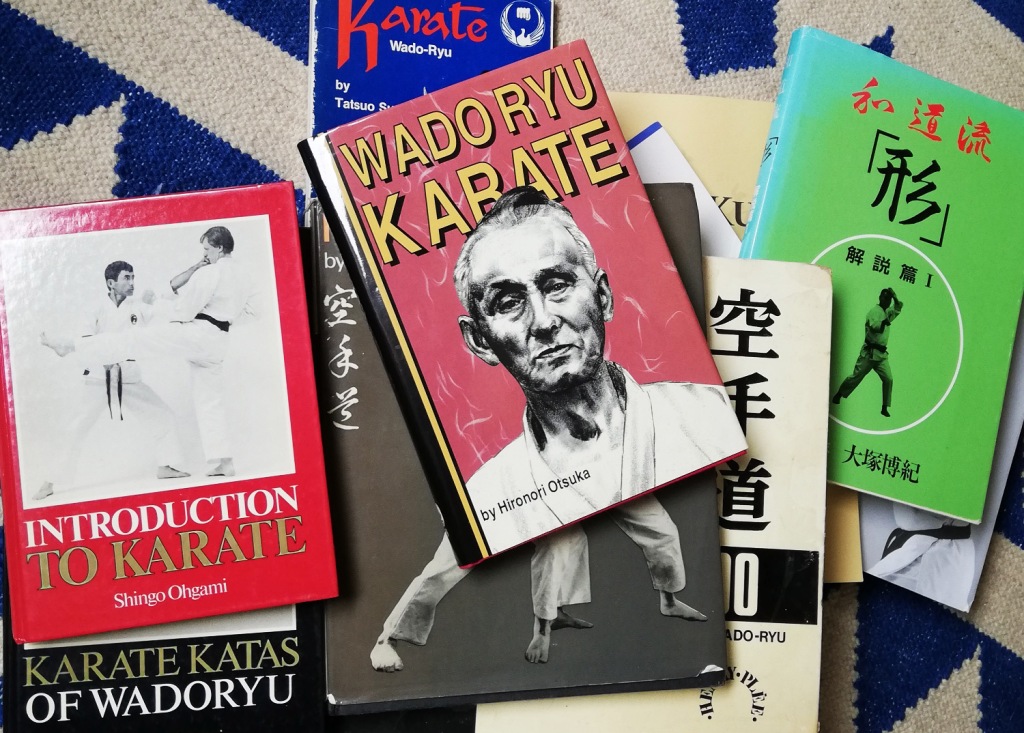

Is Wado really a style of Karate?

I am publishing this post on here as an example of the more focussed articles I have lined up for the Substack project. My postings on Substack will eventually be on two levels; free content that comes out every week and content that can be accessed by a small paid monthly subscription, believe me, it will be worth it. If you haven’t already, sign up free for the project at, https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

Btw. If you are signed up and on Gmail, be wary that it has a habit of dropping Substack posts into the ‘Promotions’ folder.

On with the theme.

Everything has to fit into some kind of category; labels must be attached and pigeonholes have to be filled – otherwise how do we know what we are describing. It is a quick way to make sense of things, particularly if we want to communicate to other people what we are talking about.

The quick shorthand operates largely because we are in a hurry – someone asks, “What do you do with your evenings?”, answer, “I go to my karate class”. The conversation could end at that point, or the questioner might ask for more information, out of politeness or maybe they are genuinely interested. And that is your opportunity to volunteer more detail.

Do we want Wado to be called ‘karate’?

But we Wado people are likely to be entirely happy to allow what we do to be identified as ‘karate’. But, is Wado Ryu/Kai etc really karate? Maybe it is something else which has not been truly pinned down, like a newly discovered genus; a wild critter that is neither ‘dog’ nor ‘cat’, a kind of Tasmanian Tiger, but still kicking around, possibly even thriving? [1]

It is entirely possible that Wado sails under a flag of convenience? I have cousins who hold both US and UK citizenship and I can’t help noticing that when they are in the UK they fly the US flag and when in the USA they fly the British flag when it suits them (really noticeable when the accents change). With Wado it very much the same; being identified as ‘karate’ has opened many doors for them, but what about its other possible identifying qualities, what are the competing factions?

Let me try and lay out the case… with some provisos, I am not Japanese and I run the risk of looking at this from a very western viewpoint, so everything here is conjecture and opinion.

Let me start with the easy one:

Wado as Japanese Budo.

This is where we apply the national pride and cultural credentials to Wado. It has such deep roots that to explain it would be like trying to untangle spaghetti. This is the bigger ‘identity’ issue. ‘But Wado was only recognised as an entity in 1938’! – I hear you say. Maybe, but, as we will see, the complexity of the history of Japan’s own indigenous martial systems is not to be taken lightly, particularly as it applies to Wado.

Personally, I quite like the ‘Wado is a distinct form of very Japanese Budo’ angle; it ties it neatly to the unquestioning high cultural and moral characteristics of anything that falls into the category ‘Budo’. But, as we know ‘Budo’ is a broad grouping and can be annoyingly difficult to pin down, especially when it uses high-minded and sometimes vague terms in which to describe itself.

But the subtext here should not be skipped over too quickly – ‘distinctly Japanese’, we are now talking about Budo as a kind of cultural artefact, one that has to be wrapped in the flag. But ‘distinct from’ what?

Historically, indigenous Japanese arts have had their heyday, and since Japan took to embracing all things western, these ‘arts’ slipped in the category of anachronisms; they were considered out of step with the direction Japan saw itself going in. For industrial Japan there was no going back, and, it has to be said, the Japanese performed economic and technical miracles; certainly, pre WW2, where things then went more than a little sideways.

Then came a time when these ancient arts needed to either be rescued from decline or completely resurrected, and, in the marketplace for oriental martial arts they had to stand up for themselves and proclaim who they were. This ‘claiming of the national identity’ came a lot earlier than most people think; it could be said that ‘karate’ was the first skirmish in a culture war that was yet to happen.

To keep this brief; Karate was from Okinawa, with very strong cultural ties to China, one of the earlier incarnations of the characters used to write ‘karate’ was actually ‘Chinese Hand’, so effectively this was an imported system and, considering the rocky historical relationship between China and Japan (which was to get a whole lot worse before it got better), this was not a welcome import in conservative eyes. (This all happened around 1922 and, if you’d asked someone in a Tokyo street prior to that date about ‘karate’, they’d say they’d never heard of it, it only existed in the Okinawan islands [2])

‘Karate’ had to have an image make-over to make it palatable. Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado, was a key mover in this area. He (and others) helped to make the necessary adjustments and secure karate in Japan as something the establishment would welcome.

Otsuka Hironori Sensei managed to eventually unshackle himself from the Okinawan karate system that he had previously been so eager to embrace (whether by accident, fortune or design is open to speculation) and from that base and his martial cultural roots in Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, he was able to craft something new, something distinctive, and was entirely happy to describe it as ‘Japanese Budo’ (while still holding on to the ‘karate’ moniker).

Ducks and Zebras.

‘If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck and looks like a duck…it’s a duck’. Take a quick look at the qualities that the casual observer would see in Wado karate, a kind of comparative checklist; what is it you find in most styles of karate?

- An emphasis on punching, kicking and striking; which lends itself well to a sport format.

- A training regime which includes solo kata, which all follow a similar external structure and hold on to original names which define their Okinawan origins.

- A training uniform that would not be out of place in any karate Dojo in any style in the world.

Bear with me on this one; the saying, ‘When you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras’. This is told to trainee doctors, reminding them to think when diagnosing, of the most common, hence the most obvious answer. But I recently heard a doctor explaining how this idea was of limited use and how she had once misdiagnosed a patient suffering from a rare condition. Is Wado perhaps the zebra?

Take another look at the above checklist; all but the second point can be explained away; firstly, striking and kicking are not unique to karate. Secondly, it was Otsuka who was one of the main movers in pushing towards a sport format [3]. And thirdly; the uniform (Keikogi) was just a convenient design development that happened over decades, which was inevitable really.

Point 2 has been chewed over a lot by karate people, both Wado and non-Wado, but I will offer my view in a nutshell. Otsuka saw something in the karate kata that he could use. What he wanted was a framework, no need to reinvent the wheel. What was really clever was that he transposed his own ideas on top of that framework, which, interestingly, was hugely at odds with how the other karate schools/styles used it.

Wado as Jujutsu.

Why would that even be considered?

Evidence?

The second grandmaster of Wado Ryu Otsuka Hironori II at some point decided to re-register the name of his school with the authorities (probably the Dai Nippon Butokukai) and call it ‘Wado Ryu Jujutsu Kempo’. So ‘karate’ was dropped completely and ‘Jujutsu’ was added. I am not going to second guess or explain the reason for this, I am not Japanese and I am not versed in the Japanese martial arts political world, but I will speculatively introduce a few thoughts from a very western perspective (always dangerous).

Firstly, apply a similar checklist to the one above, but for Jujutsu, and, from a casual lazy western perspective, nothing stacks up.

The first grandmaster and creator did indeed add a catalogue of standard Judo/Jujutsu techniques to the original list he had to present to the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938, but these were largely dropped (the exceptions being the Idori and the Tanto Dori). But, my observations tell me that it would be a mistake to assume that this is all there is to traditional Japanese Jujutsu, the complexity goes much further than Jujutsu tricks [4].

What about the word ‘Kempo’ (or ‘Kenpo’). Actually, this has a long history in Japanese martial arts.

The term Jujutsu did not really exist as a distinct entity in Japan until the early 17th century, before that a whole bunch of other terms were used; kumiuchi, yawara, taijutsu, kogusoku and kempo. ‘Kempo’ is just the Japanese version of the Chinese Chuan Fa, or ‘Fist Way’. This does not mean that Kempo is from Chinese boxing, that is a rabbit hole not worth going down. There is however a strong link with the striking aspect of Old School Japanese martial traditions, often associated with Atemi Waza, the art of attacking anatomical weak points with both hand and foot. There is a suggestion that Otsuka Sensei was really skilled at this prior to his first exposure to Okinawan karate and that his first Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu teacher, Nakayama Tatsusaburo was somewhat of on an expert in this field.

A conversation with someone closer to the source also suggested that the word ‘Kempo’ had been around earlier in the history of the formulation of the distinct identity of Wado, but I have been unable to verify this with documented evidence.

All of this tips the scales in favour of the inclusion of the word ‘Kempo’, but, this is just my opinion, there has to be more to it than that, there always is.

One more piece of evidence to muddy the water.

When master Otsuka had to register his school with the Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1938 he officially recognised one Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki the semi-mythical founder of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu as the founder of Wado Ryu, rather than himself. This might not be as unusual or controversial as it sounds. Firstly, there is the Okinawan/Japanese problem, so this is a smart political way of painting Wado in the right colour to be accepted in the highly conservative establishment of the Butokukai. But, Otsuka Sensei himself explained this point; saying that, because the actual ‘founder’ of karate was unknown, his best option was to name Akiyama. [5] The suggestion being, I suppose, that the Yoshin Ryu (SYR) component of Otsuka’s new synthesis was significant enough to make this entirely permissible.

There is also an historical precedent, well in theory anyway, this is to do with one of the early branches of Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu, not so very far removed from Otsuka Sensei’s root art of Shindo Yoshin Ryu Jujutsu.

In the 1700’s one Oi Senbei Hirotomi seems to have picked up the reins of what was established as ‘Aikiyama Yoshin Ryu’; a theory goes that in his efforts to claim a direct lineage for his curriculum he also used the Akiyama Shirobei Yoshitoki name in a more blatant way than just applying it to the signboard of his school, he used his name as official founder. This may have been to deflect attention away from any thoughts that his own teachings were a blend of other influences by actually saying that Akiyama was the real founder of the Ryu not Oi Senbei! Was this done out of modesty or deception? Was it even true? Who knows. It is one those mysteries that will never be answered.

Ellis Amdur puts other theories forward, suggesting that by placing a semi-mythical person as figurehead you create space to allow your new development/style/school to stand on its own feet and to become established without the glare of unnecessary criticism or accusations of immodesty. Is this perhaps in part, what Otsuka Sensei was doing. [6]

In conclusion, just what is Wado? New species, sub species, synthesis or something that defies categorisation? And, the final question; does it even matter?

Tim Shaw

[1] Tasmanian Tiger (extinct 1936), it looks like a skinny wolf, but it has stripes down its back like a tiger; in fact it was a kind of carnivorous marsupial.

[2] If you said ‘Kempo’ you might get a glimmer of recognition.

[3] Wado wants to play in the ‘sport/competition’ sandpit? Call it ‘karate’ and the door opens, it’s all very clever politically.

[4] At the time many of the listed techniques were common knowledge, even to schoolchildren, but that doesn’t make them any less difficult.

[5] Source; ‘Karate Wadoryu – from Japan to the West’ Ben Pollock 2020. An excellent resource. Who in turn drew his reference from, ‘Karate-Do Volume 1’ Hironori Otsuka 1970.

[6] Source ‘Old School’ Ellis Amdur and further commentary from Mr Amdur at https://kogenbudo.org/how-many-generations-does-it-take-to-create-a-ryuha/

Substack Project.

I have been thinking about this for a very long time, looking for a platform that works as an extension to all the effort put into this blog, and after much research it seemed that the best fit was Substack.

What is Substack?

Substack refers to itself as a subscription ‘newsletter’ but really, it’s a blogging platform which has a built-in email function that allows subscribers to opt for the cost-free content or the paid content (the latter is for chunkier items that are only available behind a paywall).

Some very big celebrity artists, writers and political thinkers are using the Substack platform; to name a few; Salman Rushdie, Garrison Keillor, Patti Smith, Michael Moore (Bowling for Columbine), Chuck Palahniuk (Fight Club), Dominic Cummings, etc.

Why?

This started a long time ago when I was researching and writing articles for the earlier incarnation of my website. I would spend months researching and writing articles like ‘The Naihanchi Enigma’ and ‘Wado and Jujutsu’, publish them on the site and later find that they’d been ripped off without permission or acknowledgement. I initially staged a fight back, but realised that everything on the Internet is up for grabs, it was futile. But the worst of it was that it put me off ever venturing into longer meatier writing projects again. However, I just couldn’t resist writing and I really relished the research and the contacts I had made along the way [1].

I have so much stuff in my back pocket.

As an example; years ago, I penned longer studies on themes like ‘Martial Arts and Meditation’, also a personal angle on what I’d observed in the development of Wado in the UK over the last 40 years (which was big enough to warrant a book on its own). During lockdown I typed many thousands of words on recollections of my own training experiences (snippets of which I have published on here as a taster). In addition, the ‘Naihanchi’ piece is in serious need of an update, as my understanding of both Naihanchi and Seishan has changed considerably. Similar with the ‘Wado and Jujutsu’ piece, which is way out of date, despite my recent efforts – my thoughts have changed yet again!

What’s the Plan?

First of all, I am concentrating on the free subscription material – shorter pieces not dissimilar in length and content from the posts on this platform. I will not be duplicating the posts on here – it would be so easy to just link the two together but the Substack posts will be more technical and theoretical in nature. My thinking is that by running the two separately this will expand the audience. It might be that the two blog platforms will take on different identities through themes etc.

I am hopeful for this new venture, but equally, if it doesn’t work out at least it was worth a go.

Link to the Substack site: https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

Tim Shaw

[1] I had useful information from such renowned martial artists and researchers like Meik Skoss, William Bodiford, Toby Threadgill and others, all of whom put me straight and extended my understanding.

I am grateful to Steve Thain for the suggestion of the name for the Substack project. I agonised over that for a very long time but ‘Journeyman’ chimed with me, as it relates to the ideas found in the medieval guild system. A Journeyman is a middle rank artisan, no longer an apprentice and some considerable way from being a master craftsman.

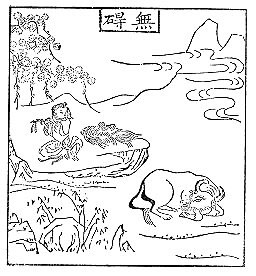

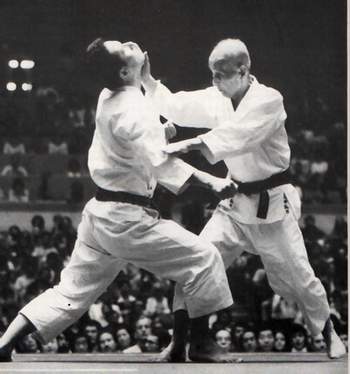

Humbled Daily.

Before I launch into this latest blog theme, just a quick word about a new development.

I wanted to extend this writing project into something bigger and so have set up on Substack, a subscription service which is really taking off. I will write a following blog post to outline my plans, but basically it is already up and running. Please support this new project. It can be found at: https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

On with the theme…

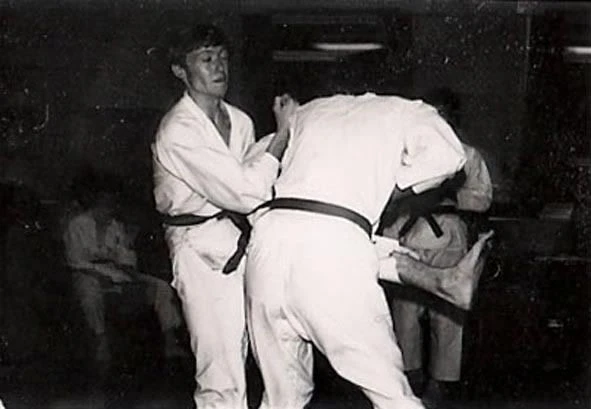

In a recent interview with movement guru Ido Portal he mentioned that grapplers and wrestlers get humbled daily, and it was a healthy thing. They roll on the mat with people of different abilities and frequently experience the challenges that such opportunities present. Often, they fail in their intentions; frequently someone else’s intentions win over theirs and they experience failure. In fact, an intense session may well involve a rolling series of mini-victories and mini-defeats. These are all valuable growth experiences. [1]

Portal says that this seldom happens in traditional martial arts, and he’s right. While not being entirely absent, it certainly doesn’t happen to that intensity.

In traditional martial arts very often the training scenario is so tightly directed that there is little space for this type of training; or, in some cases ‘loss’ is too high a price to pay that it is actually demonised, or only seen for its negative attributes.

What are the real obstacles for us as traditional martial artists to engage in parallel ‘humbling’ interchanges? Here is a list of the potential problems:

- Attitude, this might be related to ego, rank, status etc. I find it ironic that ‘humility’ in Budo is seen as a positive attribute, yet the aforementioned attitude problems are allowed space in the Dojo.

- Avoidance. We know the phrase ‘risk averse’, if you don’t willingly embrace challenge it’s going to be very difficult to improve. [2]

- The constrictions of the training format. We know that our training in traditional martial arts is limited by having to fit so much into a limited time; our priority has to be the syllabus as this is the framework upon which everything depends. How to overcome these limitations often falls on the creativity of the Sensei. Some are good at this, others not so.

- The absence of ‘Play’. Often derided, but, if we think about it, some of our most powerful learning experiences have come to us through play – we only have to think of the physical challenges of our childhood.

And what about competition and sport?

The demonisation of ‘loss’ is perhaps amplified when martial arts become sports. Although, today there is a trend where everybody has to be a winner, it’s an illogical formula. I will counter this with the pro-hierarchy viewpoint. If there is no ladder-like hierarchy to climb then there is no value system. When everything becomes the same worth there’s nothing to aspire to, no striving, no reaching, the whole enterprise becomes meaningless.

In a karate competition the winner’s position becomes of value because of everyone who pitched in and competed on that day. The winner should feel genuine gratitude towards all of those who competed against him or her, it was their efforts that elevated the champion to that top position. And, although all of those people don’t get the trophy or the accolades, they gain so much in the experience of just competing. This is the true ‘everybody is a winner’ approach.

In a healthy Dojo environment instructors are beholden to devise ever more creative ways of training to allow students to experience lots of free-flowing exchanges, where mistakes are seen as learning experiences. A while back, I shamelessly stole a phrase from an ex-training buddy who was from another system. He called this stuff ‘flight time’, as in, how trainee pilots clock up their hours of developing experience. If you get the balance right nothing is wasted in well designed ‘flight time’ in the Dojo. Over the last ten years or so I have been working on different methods of creating condensed ‘flight time’ experiences. When it’s going well there are continually unfolding successes and failures, and the best part of it is that during training everybody gets it wrong sometimes and therefore has to learn to savour the taste of Humble Pie.

Bon Appetit.

Tim Shaw

[1] I have heard similar things from the early days of Kodokan Judo, hours and hours of rolling and scrambling with opponent after opponent.

[2] ‘Invest in loss’ is a phrase often heard among Tai Chi people. It describes the lessons learned from failure. The late Reg Kear told a story about his experiences with the first grandmaster of Wado Ryu, who said something similar to, ‘when thrown to the floor, pick up change’ and then, with a smile, mimed biting into a coin.

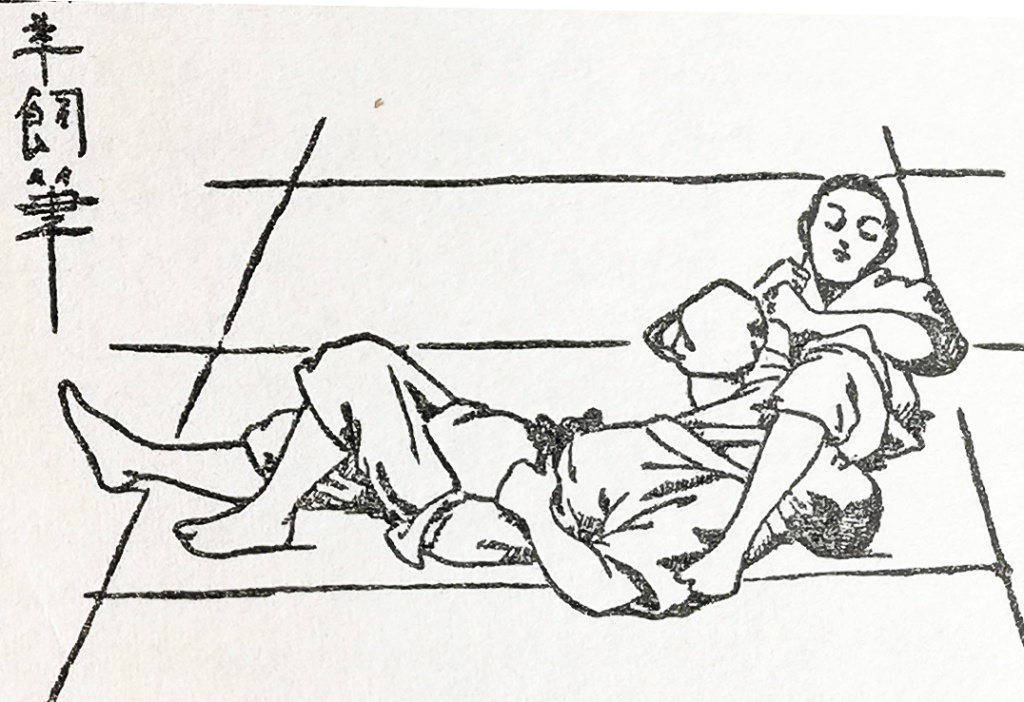

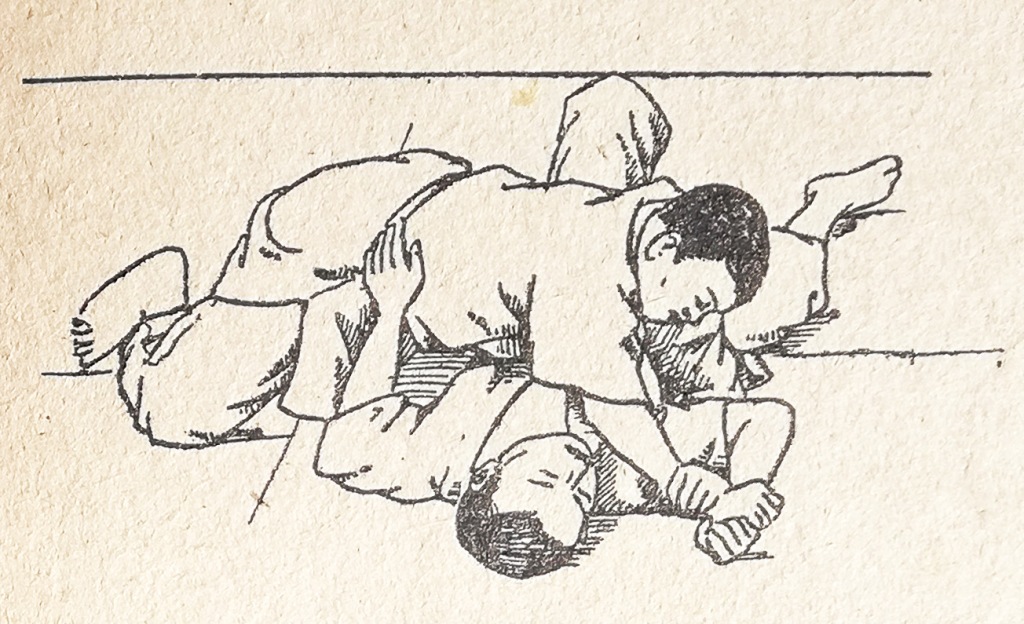

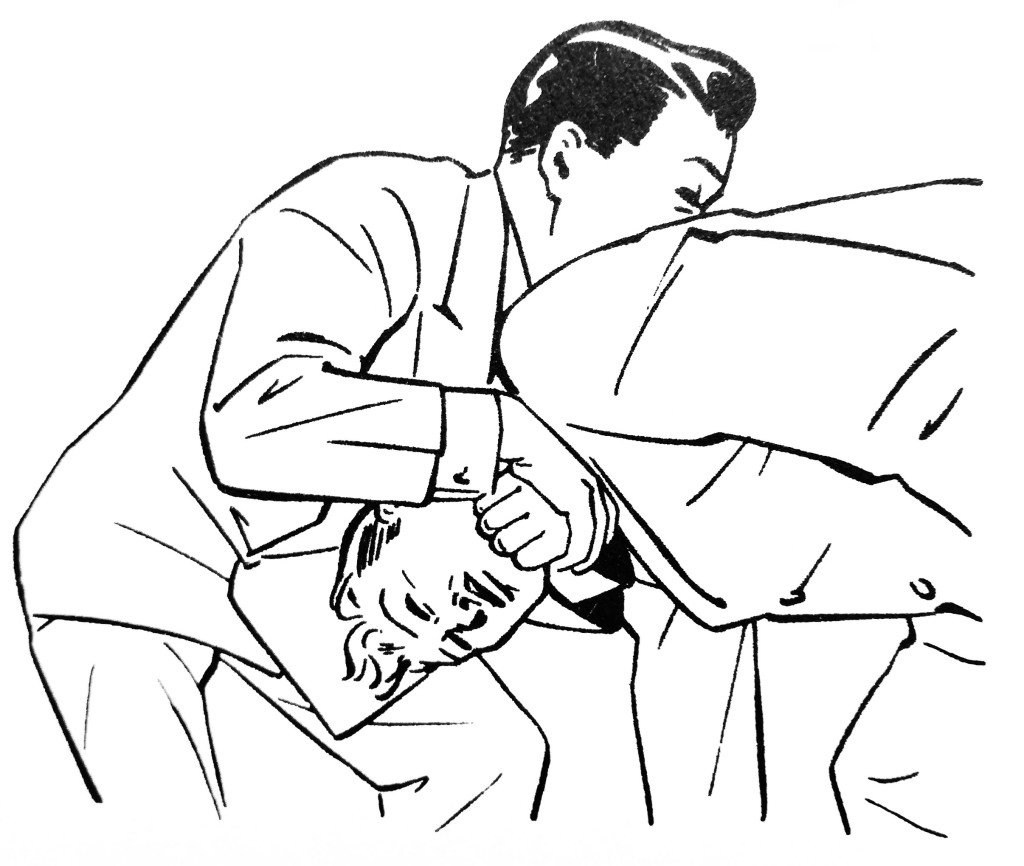

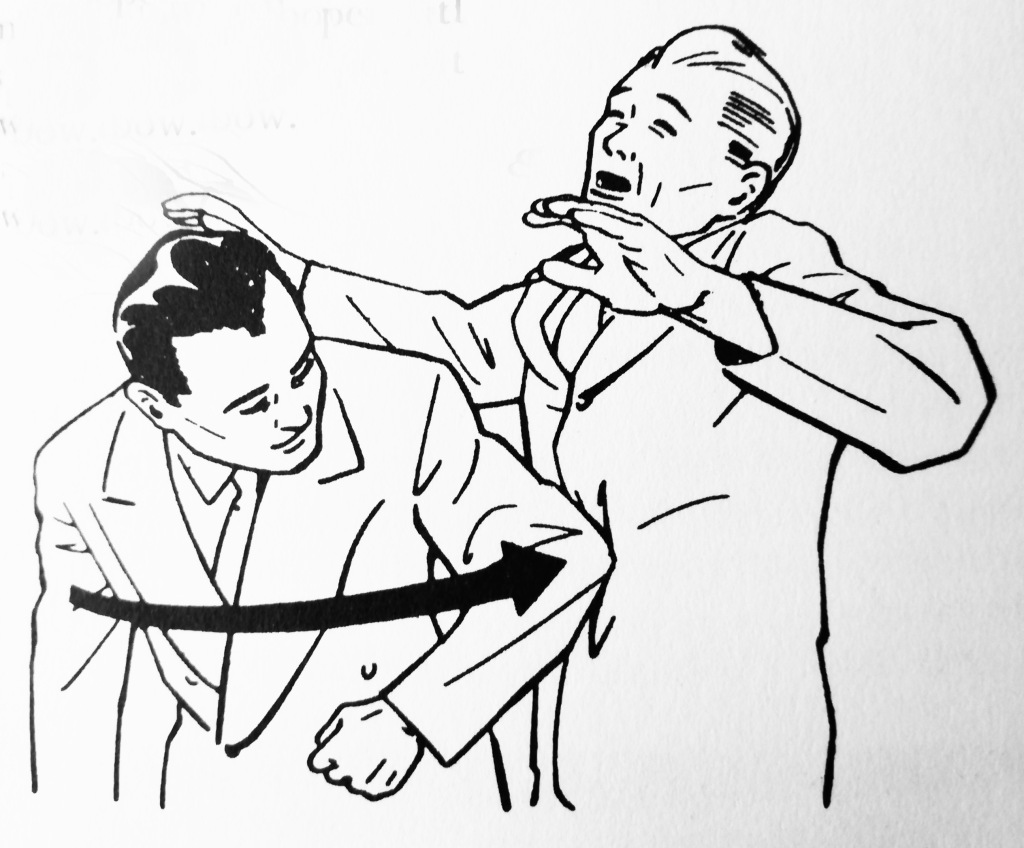

Featured images from ‘The Manual of Judo’, E. J. Harrison 1952.

Books for martial artists. Part 2. East meets West, and West meets itself.

In this second part I want to dip a toe into the way ideas originating in the far eastern martial arts migrated to the west and then morphed into something else.

Also, whether the current brands of ‘self-help’ publications may or may not have something to offer us as martial artists.

Sun Tzu – The Art of War.

If anything can be clearly categorised as being a ‘martial arts’ book it has to be Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Said to have been written around 500 BCE, this short text contains a wealth of martial knowledge and strategy. [1] The beauty of the book is that it is broad in its application and scope, yet detailed enough to pick out examples for reflection; and it plays with the conceit of being applicable to individual combat and battles involving large numbers.

People in the west have been aware of this book for as long as there has been an interest in orientalism, and inevitably it has been appropriated by the business world. So many spin-offs telling us how Sun Tzu’s book can be applied to the cut and thrust of the high-powered boardroom -everyone is looking for an edge. Titles appeared like, ‘Art of War for Executives’, ‘Sun Tzu – Strategies for Marketing’, etc, etc.

Musashi Miyamoto – ‘The Book of Five Rings’.

Musashi’s terse book on strategy and fighting suffered a similar fate to Sun Tzu. I have mixed feelings about the Book of Five Rings. At least one Japanese Sensei I have spoken to has been puzzled about Musashi’s status, as in, ‘why this guy?’, ‘Why does this dubious character deserve so much attention, when there are so many more elevated examples… Katsu Kaishu was an amazing model, yet nobody talks about him?’.

I have seen ‘the entrepreneurs guide to the Book of Five Rings’ and others have tried to piggyback on this book of ‘wisdom’.

Musashi was a product of his age, and in terms of Darwinian principles, managed to stay alive through sheer cunning and an unorthodox approach (though, what was orthodoxy in that age is very fluid. 16th century Japan was like the wild west). Again, you have to understand the context.

A quick note on the ‘Warrior’ mentality.

Excuse me for my cynicism here but nothing grinds my gears like the overuse and appropriation of the word ‘warrior’.

As a ‘meme’ on the Internet all these ‘warrior quotes’ are guaranteed to cause me to gnash my teeth in anger and frustration.

Musashi ‘quotes’ abound (which end up as not ‘quotes’ at all, just some made up cobblers nicked from another source). [2]

Just what do people mean when they refer to ‘Warriors’ anyway? Are we talking about the modern context; the professional soldier? If so, the gulf between that model and the model presented by someone like Homer when he introduced us to Achilles and Hector, or, in Japan the stories told about Tsukahara Bokuden (1489 – 1571) [3] is just too huge a gulf to be bridged; different worlds, different mentality, different technology. Unfortunately, the romantic appeal of BEING a ‘warrior’ attracts precisely the same people who lack all the idealised and fictional attributes of so-called warriordom, a domain for fantasists and keyboard heroes. Sad, but true.

To return to books.

‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’

I know that I have mentioned in a blog post previously about Inazo Nitobe’s ‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’ book. Essentially it is a confection running an agenda, in that Nitobe wanted to build a cultural bridge between Japan and the west with a distinctly Christian bias (he was a Quaker). He created an overblown link between the romanticised ideal of medieval chivalry and an equally fictionalised picture of the ‘code of the Samurai’; as such, in a nutshell, ‘Bushido’ was a modern invention. I’m sorry, but somebody had to say it.

‘Zen in the Art of Archery’.

Although this book has been influential for some time it also suffers criticism not dissimilar to Nitobe’s book. Eugen Herrigel, wrote the book after his experiences with a Japanese Kyudo (archery) teacher, Awa Kenzo. Herrigel was teaching philosophy in Japan between 1924 to 1929, the book was published in Germany in 1948. My view is that Herrigel’s achievement in writing this very short book was that he introduced the element of spirituality linked to Japanese martial training to western thinking. Although I feel a need to offer a disclaimer here… Herrigel has taken some flak (posthumously, he died in 1955); intellectual big guns like Arthur Koestler and Gershom Scholem pointed out that in the book Herrigel was spouting ideas that came from his connections with the Nazi party.

Yamada Shoji in his book ‘Shots in the Dark’ suggests that Herrigel had got it all wrong and that the ‘Zen’ element was embroidered into the story. Yamada also tells us that conversations Herrigel had with Awa Sensei were either misunderstood or simply didn’t happen.

The title alone spawned homages to Herrigel’s book – ‘Zen and the Art of Motocycle Maintenance’ comes to mind. Also, in a previous post I mentioned ‘The Inner Game of Tennis’ by Gallwey; it was Herrigel’s book that inspired Gallwey’s thinking; so, let’s not give Eugen Herrigel too hard a time.

Western books that may be relevant.

Rick Fields books are quite interesting, one in particular. Don’t be mislead by the title (based on what I’ve said above) but ‘The Code of the Warrior – in History, Myth and Everyday Life’ is a really engaging read. Fields gives us a potted history of the urge to take up arms, from the prehistoric times through to Native American culture and even a chapter on ‘The Warrior and the Businessperson’, looking at Japanese business methods and their link to samurai mentality.

Rick Fields other books have a more spiritual dimension and tend to look dated and New Age in their outlook, (written in the 1980’s); ‘Chop Wood, Carry Water’ has a clearly Buddhist vibe with a touch of the ‘Iron John’ about it. [4]

Self Help books.

Although not specific to martial arts training the so-called ‘Self Help’ book explosion may have some useful cross-overs. I had previously written a book review for ‘The Power of Chowa – Finding Your Balance using the Japanese Wisdom of Chowa’ by Akemi Tanaka. There are other books encouraging us to lead better lives that have a base in Japanese thinking, but Tanaka’s book has a clear objective of helping people to restore a meaningful balance in their lives.

I know other martial artists I have spoken to have found certain authors useful in contributing to the spiritual side of their martial arts experience. To mention a few:

- Stephen Covey, author of ‘Seven Habits of Highly Effective People’. I haven’t read it but I did read his book, ‘Principle Centred Leadership’. My takeaway from that was how much Covey was borrowing from other sources – some stand-out examples seem to come from Taoism; but useful nevertheless.

- A raspberry from me for Richard Bandler, I am suspicious of anything from him and his followers; he is one of the originators of Neuro-linguistic programming (NLP). It is, essentially pseudoscience and latest neurological research suggests that Bandler is barking up the wrong tree.

- Following a Zenic direction, Eckhart Tolle’s descriptions of the benefits of ‘living in the Now’ are worth taking a look at (though avoid the audiobook version of ‘The Power of Now’, unless you suffer from insomnia; his voice is one continuous flat drone).

- Followers of this blog will perhaps have realised that I have a lot of time for Jordan B. Peterson; however, only three books have been published [5], but the online lectures are solid gold. Peterson has some interesting thoughts on serious martial artists, who he talks about in his references to the Jungian concept of the Shadow.

The Dark Arts.

This post would not be complete without mentioning what I have called ‘the Dark Arts’. These are almost exclusively western in origin. I am not really sure where I stand on the efficacy or even the morality of these publications, but here is a list:

- ‘The Prince’, Niccolo Machiavelli 1532. The vulpine nature of Machiavelli just oozes off every page. He was a master of deception and treachery, a minor diplomat in the Florentine Republic. ‘The Prince’ is a masterwork for anyone who wants to succeed at any cost. But you might want to wash your hands afterwards.

- ‘The Art of Worldly Wisdom’ Baltasar Gracian 1647. Similar in nature to ‘The Prince’. Gracian was a Spanish Jesuit priest. Winston Churchill was said to be inspired by this book. It is dedicated to the arts of ingratiation, deception and the cunning climb to power. Just as apt today as it was then.

- Contemporary writer Robert Greene is perhaps the inheritor of Machiavelli and Gracian; in fact, he borrows heavily and unashamedly from these sources. He initially shot to fame with his 1998 book ‘The 48 Laws of Power’. The titles of his books always suggest to me as a mandate for roguery and look to all intent and purposes like a villain’s charter, as an example; ‘The Art of Seduction’ 2001 and ‘The Laws of Human Nature’ 2018. This put me off, that, and a conversation with my barber who seemed to enjoy the salacious nature of Greene’s ‘words of wisdom’. But I listened to Greene interviewed on a podcast and my view changed. Having now read ‘The 48 Laws of Power’ I realised that Greene wrote this almost from a victim’s perspective and I saw in it mistakes I had made in my past and have since bitterly regretted. A useful and humbling experience. There is more humanity in this book than I initially assumed – but also a good measure of naked ambition and dirty dealings, if you like that sort of thing.

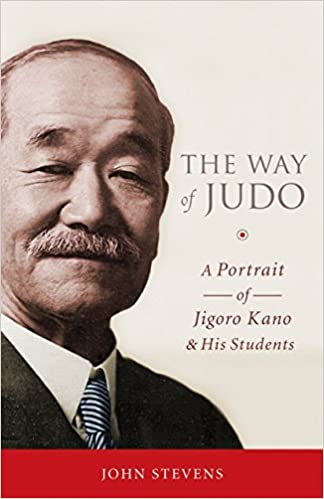

Clearly this is not a comprehensive list of everything out there, just things I wanted to share. I think there are many martial arts people who want to look beyond the physicality of their discipline and have an urge to find a wider meaning to their efforts – which is entirely in line with the broader scope of Budo, as envisioned by Japanese masters like Otsuka Hironori, Kano Jigoro and Ueshiba Morihei.

Follow your curiosity and enjoy your reading.

Tim Shaw

[1] The Penguin ‘Great Ideas’ edition is a mere 100 pages in length, with each page consisting of very short stanzas – a very simple read.

[2] The only time I felt inclined to use a ‘warrior based’ quote was a very apt one that I quite liked, “The nation that will insist on drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking done by cowards”. Thucydides.

[3] Bruce Lee’s ‘Fighting without fighting’ scene in ‘Enter the Dragon’ was stolen straight from stories about Tsukahara Bokuden.

[4] ‘Iron John – A Book About Men’ by Robert Bly. The author attempted to rescue the soul of masculinity, this was intended as an antidote to the excesses of feminism (well this was 1990!) but it was ridiculed and derided in all quarters as it became associated with all the ‘sweat lodge’, ‘male bonding’ razzamatazz, that might have been quite benign, although misguided, but quickly turned into something darker.

[5]. Jordan B. Peterson books; ‘Maps and Meaning’ (a demanding read), ‘Twelve Rules for Life’, (much easier to read and really relevant) and the latest book, ‘Beyond Order’, also good.

Image: ‘St Jerome in his study’ by Albrecht Dürer 1514. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Books for martial artists. Part 1. Lost in translation.

A two-part martial arts journey into where ‘extra reading’ can take you.

It’s only natural for us to want to boost our martial arts learning by reading around the subject, or tracking down published material that in some way gives us hints as to how to focus and direct our lives in a manner worthy of the Budo ideal.

In a previous blog post (‘Why are there so few books on Wado karate?’) I was puzzling over the fact that there are very few written sources specifically dedicated to Wado. But what about the general reader who might want to dig into history, culture or how things operate in other systems?

Publications originating in the far east.

Like everyone else, I have found myself drawn towards written material from Japan or China, with a particular fascination with the really early stuff. But of course, I have had to make do with English translations.

However, experience has taught me to be wary of these translations, as so much can be lost or completely twisted out of shape.

Here are the main problems:

- Bad translations either written with the translator’s bias, a political agenda, the translator’s preconceived ideas, the translator looking at the text through modern lenses, the translator being a non-martial artist, thus not understanding specialised language, etc.

- Misunderstandings; e.g. kanji or old style Chinese characters being badly copied [1], or so outdated as to be almost unintelligible without HIGHLY specialised knowledge.

- Things taken out of context, e.g. their historical context, or cultural context.

- Deliberate obfuscation – text written in a way that only the initiated can understand them.

Of all of the above I think it is the ‘taken out of context’ that is the biggest error. The further back in history you go the more you encounter cultural and historical contexts that are so alien they are almost undecipherable. As a comparison, think how difficult some phrases from Shakespeare are to understand. [2]

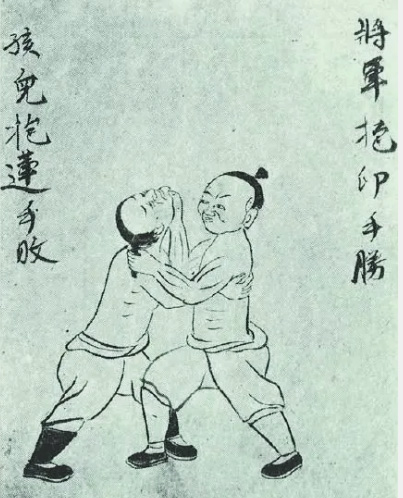

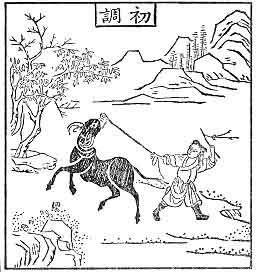

Pictures speak louder than words.

You might imagine that pictorial references, even in antiquated texts have more to offer than translations? But that also can be hugely problematic.

Here are two early martial arts examples that come to mind:

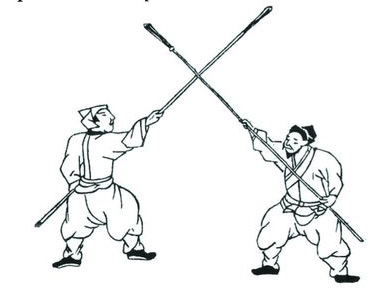

The Heiho Okugisho.

The earliest origin of parts of this martial arts book might go back as far as 1546, but really, who knows? Studies on this suggest it’s a chop-together of mostly Chinese sources that found their way to Japan and became really popular among martial arts enthusiasts in the Edo Period. It included, descriptions and drawings of techniques of spear and halberd, as well as empty-handed techniques and was eagerly devoured by aficionados and dilettantes alike and, according to one commentator, was passed around like porn mags or chicken soup recipes, with a hopeful belief that it was the real McCoy. But even with its enticing line drawings of men in antiquated Chinese dress, just about everything in it is bogus. Not to put too fine a point on it, it’s like a modern-day Photoshop fake. And still people studied it trying to tease out the ‘secrets’ hidden within and looking for the missing link of a Chinese connection to Japanese martial arts. [3]

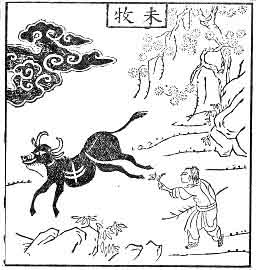

The ‘Bible of Karate – the Bubishi’.

This particular publication has a strikingly similar backstory to the Heiho Okugisho. The structure follows a comparable pattern and with the same maddening obscurities. Here is a book that was ‘kept hidden’ until around 1934 when parts of it were published in Japan. It emerged from Okinawa and so people inevitably connected it to Okinawan karate. It’s a book comprised of Chinese self-defence moves (line drawings and brief descriptions), various sections connected to herbalism and a questionable set of visual diagrams relating to ‘vital point’ striking. Much of it is written in flowery ancient Chinese characters that only the initiated have a hope of understanding.

When it was released as an English translation in 1995, I was eager to get my hands on it. Yes, it was intriguing and I studied it closely, trying to extract some kind of meaning from it. The drawings I could relate to, but any techniques I could find in them were quite basic; but really, what did I expect to find in line drawings with no meaningful accompanying text? Essentially, as a ‘how to do it manual’ it was (for me at least) a failure.

Over the last twenty-seven years more critical and well-informed eyes have examined the Bubishi and in some areas it is just not stacking up. Take for example its claim that it related to White Crane Chinese Gung Fu, and thus suggesting a clear link with Okinawan karate to a Chinese root. Apparently, according to experts in the field, White Crane has so much more to it than that, AND the ‘vital point’ diagrams look more and more like pure fantasy. [4] [5]

Here’s another one; not a book but a document:

“Itosu said…” well, did he really? And if so, what did he actually mean?

Some karate enthusiasts have eagerly brought their gaze towards an obscure, very short letter written by Okinawan karate master Itosu Anko (1832 – 1915) [6]. The letter was written to an Okinawan school board in 1902 and its intention was to explain in ten bullet points the virtues of karate training in the education system and a few basic guidelines as to how to approach training – to keep you on the right track. The letter has value by virtue of the fact it survived. In Okinawa so little was written and most of what was ended up in ashes as in 1945 the American forces had to pretty much raze large sections of the Okinawan islands to root out the resistant forces. But, as a cultural artefact Itosu’s letter is a hell of a rarity and really that is where its value comes from.

Some enthusiasts have rightly acknowledged the translation issue but have found themselves chasing after the wrong rabbit and have suggested that it is better to have a non-martial artist, non-specialist do the translation. Actually, it is that very problem that ruined Otsuka Sensei’s book for western audiences, because the English translation done by a non-martial art specialist misses out the nuances and implications of Otsuka Sensei’s carefully chosen characters.

With Itosu’s letter it is incredibly difficult to tease out anything beyond platitudes and generalisations, it’s not ‘The Da Vinci Code’ or the ‘Mayan Prophesies’, it’s a letter with a clearly defined audience in mind (the school board) and it pretty much does the job. For some people it has become a kind of manifesto, but if that is the case it is thin gruel. Yes, it is interesting, particularly as a snapshot in time and place, we can learn a lot from it as a cultural icon and there is much to gain from this window into a world long gone.

There are too many books and publications to go into in this post but I would like to put in some recommendations that particularly chimed with me and that I am prone to go back to time and time again.

- ‘The Unfettered Mind’ Takuan Soho. I have always loved this book, written some time in the 1630’s by monk/scholar Takuan Soho as a series of essays directed as guidance to the famous Yagyu clan of swords masters, teachers to the Shogun. The suggestion has always been that it was a Zen text but contemporary expert William Bodiford puts a good case that it is really a Neo-Confucian work (to me it fits far better than the contemplative approach of the Zen school of thinking).

- ‘The Tengu-Geijutsu-ron’ of Chozan Shissai (translation by Reinhard Kammer, published as ‘Zen and Confucius in the Art of Swordsmanship’). Written around 1728. Shissai expresses his ideas in a novel format and has harsh words for the swordsmen of his generation. The philosophical content and mindset come to life once you realise what he means by ‘Heart’, ‘Mind’ and ‘Life Force’ as it relates to Japanese martial culture. But there are some clever models and ideas scattered throughout the text.

- ‘The Sword and the Mind’ ‘Heiho Kaden Sho’, translation by Hiroaki Sato. The core essays date from the mid 1600’s and comprise practical guidance by the above mentioned Yagyu family. A great history section, but there is considerable content on the Mind and strategic outlook for the professional swordsman.

It won’t have escaped your attention that the above examples are all from swordsmanship, but it is my feeling that Japanese Budo/Bujutsu is well represented through the refinement of the art of the sword; particularly as it relates to the high level of psychospiritual culture that developed over many centuries and probably reached its zenith in the 17th century. The relevance of this is still present in our approach to training in modern martial arts, particularly Wado; weapon or no weapon, we carry a technical legacy that should still be with us, and we should always be trying to identify and reach towards those rarefied goals.

Conclusion.

Ultimately, reading any reliable material in and around your pet subject has to be a good thing. Understanding context, in particular, is crucial to getting under the skin and really understanding what you are doing. Many systems have depth and history and have gone through refinement and transformative processes to get where they are today. Generally speaking, reading is one of the most sure-fire ways of journeying into the cultural lineage of your system.

My view is that reading gives you glimpses of a mindset that is so very different from our own, whether it is the Itosu Letter or master Otsuka’s terse poetic axioms [7] it is clear that the time, the place and the culture inevitably wired-in ways of thinking and looking at the world that have entirely different priorities to the ones we have today. Yes, there are universal principles like justice and a desire for peace, but the societies were structured on pre-industrial almost feudal models (or were in the process of struggling to break free of those models) so it would be a mistake to simply project our views on to their writings.

In part two I intend to take a brief look at more modern examples (that may or may not be written with martial artists in mind) and look at how the west chooses to utilise eastern examples.

Tim Shaw

[1] Early text were hand copied, often generation after generation, remember, printing presses only worked well with European alphabets. Errors occurred, and then were magnified (Chinese Whispers).

[2] I have a particular fascination with the I-Ching, (said to be over 5000 years old). On my bookshelves I have five versions which I tend to compare against each other, the differences are quite startling.

[3] Reference; Ellis Amdur, ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’.

[4] See, https://whitecranegongfu.wordpress.com/2014/12/02/the-bubishi-myth/

[5] Consider the story of how Doshin So the founder of Shorinji Kempo was inspired to create his system after observing a mural painted on the wall of the Shaolin Temple, when he visited in the 1920’s and 30’s, showing Chinese and Indian monks training together. Although Shorinji Kempo history states that it was actually the spirit of training together that inspired Doshin So, not necessarily the technique. But it goes to show how pictorial imagery can inspire ideas.

[6] Itosu Anko is a very important figure in the more recent story of Okinawan karate and features at the point just before karate jumped from the islands to mainland Japan in the form of Itosu’s student Funakoshi Gichin, who was incidentally the first karate teacher of Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado Ryu. So, in some ways Itosu can be seen as the ‘grandfather’ of the Okinawan karate element contained within Wado.

[7] Master Otsuka composed short poems to express his ideas of how martial arts should function in the world. An example, “On the martial path simple brutality is not a consideration, seek rather an intense pursuit of the way that describes peace”. Source, article by Dave Lowry, ‘A Ryu by any other name’. Black Belt magazine, May 1986.

Bubishi Image credit: ‘Sepai no Kenkyu’ Mabuni Kenwa.

How detailed is your Wado map?

How confident are you about what you know of your system, the discipline you have chosen to study? Are you comfortable with the information you currently have to hand? Do you think you understand the roadmap of that developing knowledge, and is its trajectory obvious and predictable?

Okay, so, I accept that any Wado practitioner reading this might well be at very different points in their journey; some may be just beginning their study, others might be senior practitioners with many years behind them, but the ideas I am going to put forward I am fairly sure would benefit all – or at least stop and make you think. That’s the plan anyway.

Maps.

I am going to start with the broader idea, something I heard a little while ago. There is a theory that we all keep a complete map of the world within our own heads – a personal hardwired version like Google Satellite, Street View and Maps. When I first heard this, I was sceptical.

While I am fully aware that the human brain is perhaps the most complex thing on the planet but really this seemed a bit too far-fetched. But, it is true. That mess of grey matter that sits between our ears that has no awareness of itself outside of its own input devices – our senses, can really do all that, and more!

This amazing mapping, navigation device does not just include places, it also acts as our own personal encyclopaedia, with just about everything there is to be referenced. I use the word ‘referenced’ in a very deliberate way because the reality is that ‘references’ are about all we get.

To explain; while we have this map/encyclopaedia in our head most of this information is patchy and, in many cases, extremely low-resolution. The truth is, we have low-resolution representations of the majority of things we think we know.

Examples:

- Ask yourself about a random country in the world; say, Vietnam? Can you point to it on a map? Probably, but what else can your personalised encyclopaedia tell you? History, culture, language, currency? Unless you know the country very well through direct experience your knowledge will be sketchy, very low-resolution.

- Another couple of words; ‘Steam Train’. To communicate your understanding of this mode of transport, you might draw me a picture of a steam train, complete with funnel and wheels and a cab, all very ‘Thomas the Tank Engine’ – but unless you are an insanely enthusiastic trainspotter with qualifications in engineering and skills in mechanical draughtsmanship, I am not going to be convinced that you really understand a steam train, it will be extremely low-resolution.

Okay, so there are things we might be VERY knowledgeable about (or THINK we are), but the reality of our ‘wired-in’ intelligence and retrieval system (brain) is that it is in a state of constant update, or at least it should be. The truth is that (hopefully) more depth of information is being added and redundant (false) files are being deleted or replaced and new entries or categories are being added.

In some areas, people actually choose not to update their maps and files, this is often found when people become entrenched in areas like politics. Clearly, individuals can be so profoundly tribal in their political beliefs that even in the face of irrefutable evidence they will argue that black is white. But that’s their problem.

How about Wado (or any martial arts system)?

All of the above can be applied to our understanding of Wado karate.

I think it’s a case of being totally honest with yourself; particularly those who have been on this pathway a long time. Come on, do you really believe the same things that you did twenty years ago? How have your files been updated?

An example:

I came to the conclusion a long time back that just about everyone I knew in the martial arts continued their training for completely different reasons than those they started with. It might have been that they initially wanted to build confidence; they were fearful about their ability to protect themselves; but then, over time, their maps changed, their references became more sophisticated, more nuanced and they found something new, something of substance. I can’t get into describing what that is in this post, I don’t have the space; (in some ways I explored this idea in my blog post ‘Martial Arts training and the value of finding your Tribe.’).

Your Wado map.

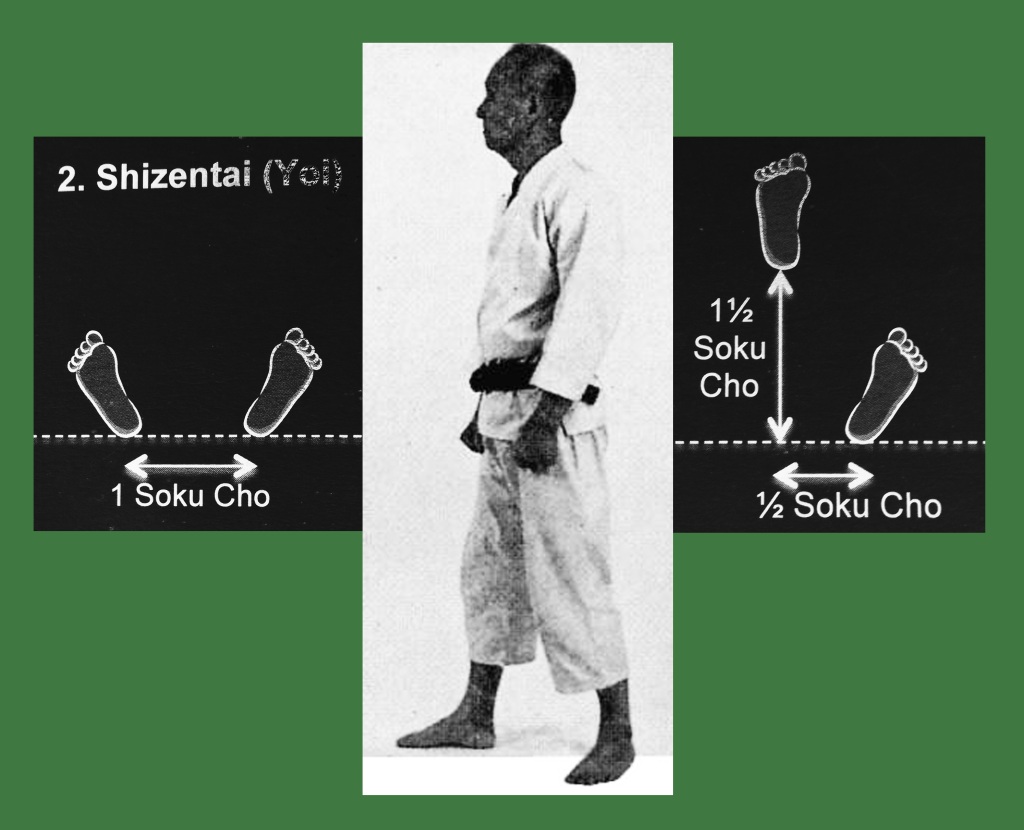

For every student of Wado karate your initial ‘map’ is usually found in the pages of your syllabus book. This map expands as you move through the grades. Although, I must say, the reality is, it’s not an easily accessible map because it is mostly written in a different language.

But it would be naïve to assume that when we have completed the book we have mastered the system, it doesn’t work like that. The syllabus is a very low-resolution representation of the system; really, it’s a loose framework designed for convenience. In addition, ‘knowing’ the book, with its Kihon, Kata and Kumite doesn’t guarantee you can actually do it; and doing it doesn’t mean you can apply it. Imagine a musician who can read sheet music but can’t play an instrument, or who can play the music accurately but cannot improvise!

The downside of the syllabus book.

In Wado I don’t think reliance on the syllabus book is particularly helpful; it’s a pretty poor map. For me it’s too linear. For systems other than Wado it might easily describe the structure in a straightforward and accurate way, but within Wado karate it only takes you so far in understanding the true nature of this very unique Japanese Budo system. In fact, I would go so far as to say that if the book is the only model/access route, it will ultimately lead you down a dead end. [1]

A different map.

In some of my more recent teaching seminars I have presented a completely different map; a pictorial diagram that I think enables Wado students to navigate a more useful and meaningful way of understanding Wado – but a blog post like this is not the place to share this idea; besides, it is still a work in progress, as it should be. [2]

Expanding the map or increasing the resolution?

I think it is too easy to misread what I mean by developing or expanding the map. I don’t think that the Wado map should be seen as a kind of growing, territorial colonialisation, similar to a video game like ‘The Settlers’ or ‘Minecraft’ where from a tiny localised centre you keep occupying new territory and building new structures; that would be like adding extra pages on the end of the syllabus book.

To give a concrete example: Otsuka Sensei was quite content with the idea of nine core solo kata, anything beyond the apex kata of Chinto was classified as ‘extra’. [3]

Paired kata are perhaps another story. If you take them on face value, they are legion! But to focus on their bewildering number is perhaps missing the point.

I speculate that with the paired kata there is a hidden map lurking beneath the seemingly complicated map which features, for example; the ten Kihon Gumite, the thirty-six Kumite Gata, twenty-four Ura no Kumite and all the rest. The clue is when you acknowledge the reality that none of these paired kata contradict the core principles, and it is these core principles that are the real map, the one skulking underneath, and, in content, the ‘Principle Map’ is not such a huge numerical challenge.

The most valuable approach is not necessarily to expand the territory, but to increase the resolution. The territory might well push beyond its boundaries but only in a natural, unforced way, an organic by-product of more defined and focussed examination. The real payback is in the more granular exploration of areas you already think you know.

‘Low-resolution’ has its uses.

Low-resolution thinking is natural to us, it’s the very basic of what we needed to survive and has been with us for tens of thousands of years. But what might have been paramount for hunter-gatherers has now slipped down our list of priorities – I mean who needs to clutter up their thinking about what they might have had for breakfast when they are being chased by a sabre-tooth cat? A boost of adrenalin and the most basic info about an escape route should be enough!

What does ‘increasing the resolution’ mean for your Wado?

Let me start with what it does NOT mean:

- It does not mean knowing more and more about less and less.

- It does not mean you become a slave to detail, which, if taken to its extreme can result in you looking like an obsessive dilettante, all ‘head knowledge’ and no practical/physical skills. [4]

- It does not limit your thinking by allowing you to assume you have it all pinned down. Actually, the reverse should happen; your mind continues to expand.

What it DOES mean is:

- The more granular your understanding the more you appreciate the relationships between the various parts of your Wado map, the underpinning logic.

- This increased resolution enhances your creativity.

- If approached with humility, you begin to realise how little you know, or how things you thought you knew might have been wrong.

How to adopt a ‘granular’ approach to something you thought you knew.

As an example; never, never, never underestimate or dismiss Kihon, I say that because if you take something like the action of Junzuki, this single technique taught at the beginning of your training reveals so much more depth. Why do you think that no matter how many years you have been training you never leave Junzuki behind, you never transcend it? It’s always a work in progress.

But I guess you expected me to say that.

Another example: Take something like the role of ‘Uke’ in paired kata… it took me far too long to realise that Uke is not a mere stooge for the person performing the prescribed technique. Uke has more say in the conversational process and this ‘conversation’ continues all the way to the end of the kata.

The double-edged sword.

I left this part till the end, but it is incredibly important. Essentially, having knowledge in your head is no good on its own. For it to be given any form of concrete real-world potency, the other form of ‘knowledge’ must accompany it; that is the absorption of the technique into your body, to borrow someone else’s rather excellent description; it must be so deeply engrained that it stains your very bones!

Tim Shaw

[1] Yes, we have a syllabus book in Shikukai, and yes it has its uses as an outline, a catalogue of techniques and requirements for grading, but that’s it.

[2] I have been toying with the idea of sharing this type of material through a subscription service like Substack, but I haven’t made my mind up yet.

[3] Notice how the kata Suparinpei dropped off Otsuka Sensei’s map very early on. Also consider Otsuka’s early development of Wado and look at the list of techniques produced for the official registration in the 1930’s; it’s a kind of map, but what was its objective? Who was the map really for?

[4] ‘Dilettante’, I like this much underused word. Definition; ‘A dilettante was a mere lover of art as opposed to one who did it professionally.’

Photo credit: The Settlers screen image courtesy of: https://www.sockscap64.com/games/game/the-settlers-2/

Competition karate – Is this really the way it’s going?

Looking at the latest manifestation of karate as a competitive entity I honestly wonder where the current trends are taking us?

This is a genuine question; I’m not saying I have answers, but I am going to try and unpack my own thoughts through the process of writing.

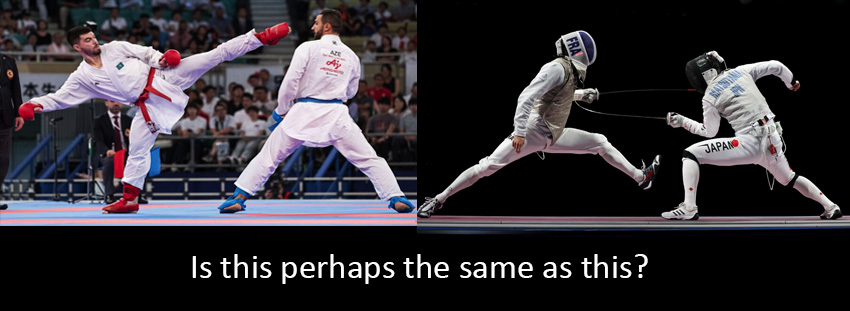

First; examine my image at the top of this post. Is there any truth in this view? Is competition karate turning into an empty-handed version of Olympic fencing?

For me this came out of a conversation I had while teaching in Europe. An instructor, who is much more engaged with the modern competition scene than I am, proposed this comparison to me, and I was quite shocked really. Since then, my Instagram feed of seemingly endless competition karate training drills, contest clips etc, have all taken on a different guise – once the thought hit me I couldn’t un-see it, this looked like fencing!

Maybe others have come to the same conclusions?

In the process of writing this post I discovered that ‘Karate Nerd’ Jesse Enkamp had also dipped into this area, and, in part, came up with a similar comparison [1]. In this mini-documentary, as an interviewee, he presented an interesting comparison between competition karate from the 1980’s and 90’s and the most modern version. At one point he said that the 1980’s/90’s example featured competitors who were ‘determined to win’, while modern competitors are ‘determined not to lose’. The point he seemed to be making acted as a reinforcement of an observation that modern day karate competitors are so wired that they seem to be perpetually on a knife edge; with the suggestion that perhaps those historical competitors, in their crudity and aggression, could somehow disregard this necessity? I have my doubts.

Perhaps it’s more complex than that?

Maybe it is the pressure of the modern competitor to ‘not lose’ by points alone; whereas his historical counterpart would perhaps ‘lose’ in more than just one way? For example, he might experience loss by, sheer domination or aggression, or just being purely physically overpowered by strength or prolonged staying power AND lose on points? [2]

Mindgames.

The modern competitor surely must be developing a mindset similar to that of a top seed tennis player? I would refer anyone interested in this to Timothy Gallwey’s ground-breaking 1974 book ‘The Inner Game of Tennis’. This book launched a whole industry of peak performance sports psychology, focussing on cultivating a mental state which enabled the highest level of sporting achievement. Interestingly Gallwey ‘discovered’ these techniques through exposure to meditation back in the 1970’s; now where does that sound familiar?

Specialisms.

The modern karate competitor is a specialist; the concept of the ‘all-rounder’ (the person who wins both the kata and the kumite) probably died in the 1980’s, and in those days, they had to prove themselves through huge, continual rounds of eliminations, not in some minor domestic contest.

You can’t take it away from them, as a specialist the modern karate contestant has developed superb athleticism, clearly the domain of the very young. Remember, what the Olympic fencer does with one hand (albeit with a 110cm extension) the karate athlete has to do with all four limbs; that is a heck of a lot to have to look out for!

‘Karate Combat’.

A final word on ‘Karate Combat’, a new franchise/business/media phenomena developed in 2018. An unashamed crossover between sport and showbiz, whose founders credit the emergence of ‘Cobra Kai’ as contributing to their ‘timely’ success.

My view is that if you stick around long enough the same ideas roll round time after time. This same idea was happening in the 1970’s; the American version at that time made stars of Benny ‘the Jet’ Urquidez and Bill ‘Superfoot’ Wallace. This is almost the same, only packaged for the ‘Mortal Kombat’ generation, with all the modern digital glitz.

It is interesting what COO/President of Karate Combat Adam Kovacs has to say about his product: “This is something that karate itself has been kind of crying out for in a way, because anyone with a background in karate beforehand would have only had the option to switch to mixed martial arts, whereas now if they want to fight full contact they can put their years of training to the test at the highest level….We think we are not only doing a favour to karate but also to the entire martial arts community who have grown tired of the copycats because pretty much every single one of these other promotions are trying to copy what the UFC is doing”. [3]

Bear in mind that Kovacs was a successful Hungarian sport karate competitor from 1998 to 2010. I have watched a little of the Karate Combat output, but always come away with the same nagging doubts; particularly, why is it that the fighters have to compromise their technical karate base (if we assume that’s where they came from) to be successful? Even the great modern karate competitor Rafael Aghayev has to depend on the wildest haymaker punches to make it work, to generate the power? [4]. To my mind Aghayev is a full-on class act, but my guess is that in this particular arena he has to resort to the common mode. Maybe it’s not so much a reflection of Karate Combat or Aghayev and the other competitors; perhaps it’s a reflection on the current mode of sports karate?

Like I said at the beginning, I am still working this out, all I can come up with is observations and questions, but no conclusions. But, just where are we going with this? After all, the Olympic karate pony never really got to the starting gate – good thing or bad thing? You can make your own mind up.

Tim Shaw

[1] ‘Martial Arts Journey’. Old school karate link

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SYp3BLXYBsk

[2] What is interesting about the examples of ‘old school karate competition’ is that they seem to be mainly from the UK. Look out for Alfie ‘the animal’ Lewis in that very interesting foray where, then karate England manager, Ticky Donovan decided to field a freestyle ‘star’ of his age, as a karate competitor. It didn’t work because Alfie operated in a very different format – I think you can see that in the footage (those of you who can recognise Alfie Lewis).

Also watch, Elwyn Hall, Shotokan KUGB supremo.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E7KYvluiN-k

Fencing photo credit: https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/sports/fencing-france-roc-face-off-mens-team-foil-gold-2021-08-01/

Karate photo credit: https://www.ispo.com/en/markets/everything-about-karate-premiere-olympic-games-tokyo-2021

[3] Karate Combat Interview Adam Kovacs quote: https://www.givemesport.com/1719277-karate-combat-is-carving-out-its-own-path-in-the-crowded-space-of-combat-sports

[4] Watch Aghayev’s Karate Combat bouts on YouTube slowed down and you will see what I mean.

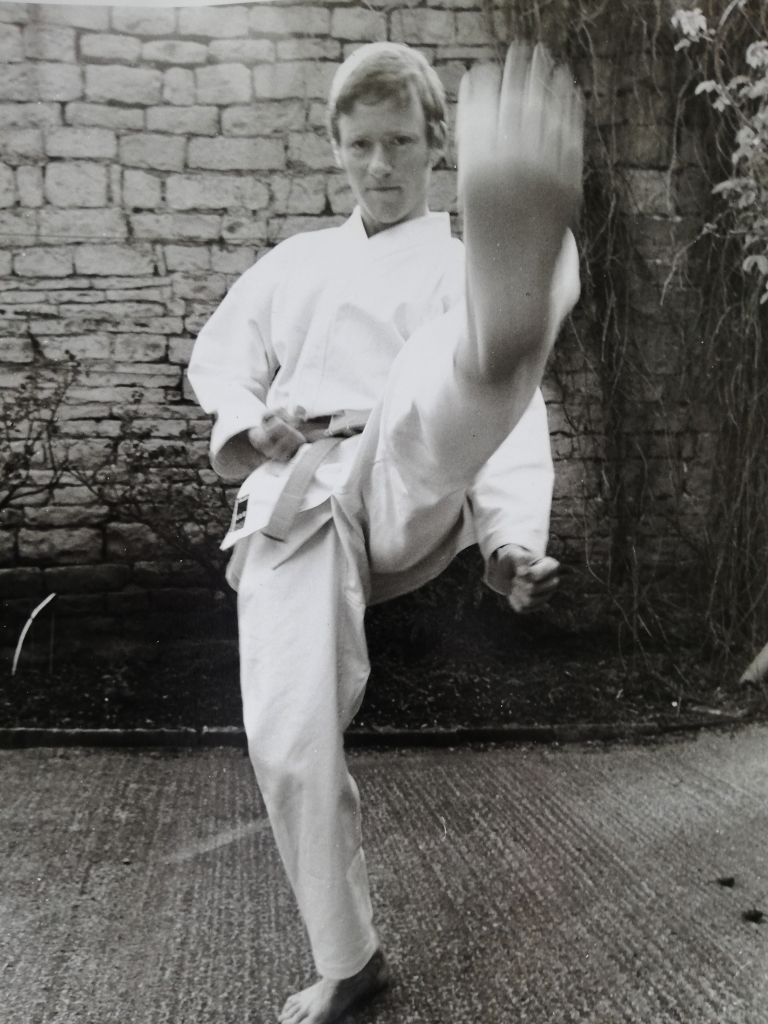

Sample – Part 23, Foreign Parts.

Memories of far-flung locations – have Gi, will travel.

I had always had a longing to travel and explore the world beyond the UK. As evidence for this; during 1981 while I was still wondering what I was going to do in the future and still in Leeds, as a long shot I applied for teaching positions in Tokyo, but with no success. I mention this because I was very flexible in my outlook and prospects and was pretty much prepared to do anything at that time.

Fast forward to later in the year; I sat in a bar in New Orleans chatting with a guy who was on furlough from a Gulf oil rig who told me there was money and travel to be had in the oil industry, though the work was tough. With a wink, he told me that the real adventure and good life was to be found in South America. On the back of that, while I was in Louisiana, I actually went for an interview for a job as an off-shore roustabout on a rig in the Gulf of Mexico. The process stumbled at the last minute when I realised that I needed a Green Card – no Green Card, no job. If that had gone through, any plans I had put in place previously would have just gone out of the window. I suspect that my life would have taken a very different turn if I had gone into the oil business.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

To return to the timeline.

Back in Leeds.

I’d previously hedged my bets by applying to get a Post Graduate teaching qualification. At the time I referred to it as ‘just another string to my bow’, something I could fall back on and dip in and dip out of. But it didn’t quite work out like that.

I got on to the PGCE course in Leeds because I had excellent references and the prospect of a good Honours degree. I also wasn’t quite prepared to abandon my life in Leeds; I had too much invested in it and was reluctant to say goodbye to a city I had loved so much.

But travelling was still on the agenda.

There was a plan that Mark Harland and I were going to do the States in the August of 1981. He and I had travelled abroad together before.

France.

Previously, back in 1979, Mark and I took the boat train to Paris and, once we’d exhausted the capital, we decided we’d explore France. Paris was fun, though I have an abiding sickly memory of trying to shake off the grandmother of all hangovers in the Louvre.

The day we finally chose to leave Paris we had a plan and our logic told us to travel to the furthest end of the Metro system heading for a motorway slip road where we could hitch a lift. But the day we picked was the same day as a rail strike; so, when we got to the slipway ramp we were faced with a queue of about twenty other people all with the same idea. We didn’t help ourselves; we set a target of the town of Chartres; it must have been the A11 as our real target was Le Mans. We wrote the word ‘Chartres’ on a piece of cardboard, but we spelled it wrong!

Against all the odds we got a lift from a young woman in a blue Citroen. At first I couldn’t understand why a woman on her own would pick up two male hitch-hikers, but, whether by accident or design, she gave us the message that she wasn’t the type to be intimidated by two young English guys, this was when she reached forward to where I was sitting in the front and flipped open the glove compartment and there was a revolver just sitting there. Nothing was said, no explanation; I still struggle to make sense of it today.

I mention this because it was on this hitch-hiking adventure that I discovered that Mark and I were compatible travel companions, and, out of this, the American plan was hatched.

However, fate stepped in and the whole project was thrown up in the air (literally) a couple of weeks before we were due to fly out to New York, when Mark rang me and told me he’d had a motorcycle accident and broken his collar bone. I thought about cancelling the trip but the belligerent side of me thought ‘what the hell’ and I went on my own. This went down badly with my then girlfriend as she thought she could ride in on that ticket, but I thought differently. Although she wasn’t happy, later on she typically got her revenge. But that is another story.

New York.

I flew over to New York from London on one of the first no-frills budget airlines, Laker Airways, owned by entrepreneur Sir Freddie Laker. Freddie was actually on the trip himself and went round shaking hands with the passengers. Laker Airways went bankrupt a year later, a victim of the early 80’s recession. The flight was cheap because I bought a ‘standby’ ticket, basically you went on spec.

Apart from the trip to France I’d never travelled abroad before; family holidays were limited to typical UK holiday resorts.

I had relatives in the States and hooked up with a cousin who was married to a Coastguard officer. I stayed some of the time with her and the rest travelling around on my own.

I initially took the Greyhound bus from New York to Buffalo with a brief stop off at Niagara Falls. Then went down the length of the country through Cincinnati and all the way down to Baton Rouge and to New Orleans.

Hitch hiking.

Solo travelling is not without its risks. While travelling I had more than one brush with religious cults who were keen to prey on lone foreign travellers, particularly the Unification Church AKA the Moonies. I didn’t fall for it.

At that time I had a lot of confidence, verging on the reckless and naïve. I had so much belief in my ‘magic thumb’, (the hitch-hiking thumb that did Mark and I so well in France with). I reckoned on using the same technique in the USA.

In the time I was travelling around on my own I chose to stay in the Southern States. I used the Greyhound bus for some journeys; it was cheaper to sleep on an overnight trip on the bus and wake up in a new city, but it was sometimes arctic cold with the intensity of the air-conditioning. I hadn’t packed much in the way of clothing; in fact, I hadn’t packed much at all. I had a shoulder bag, like a two handled Adidas sports bag in which the bulkiest item was my Keikogi. I was living a bit like a tramp.

Generally, the hitch-hiking worked out well for me. I had stitched a Union Jack onto my bag and, while it was useful for the lifts it singled me out too much as a tourist in the cities, it was more useful to just blend in; so, I ended up ripping it off.

I tended to get lifts from pick-up truck drivers, almost always old boys who had been in the military during the war, some asked me if I knew Mrs Brown who lived in Southampton (I guess it was better than asking me if I knew the Queen!). The natural assumption was that the UK was so very small compared to the USA, so everybody knew everybody else.

I had no idea that hitch-hiking was illegal in some states and found this out the hard way.

At some point I fell in with another young guy also hitching. We planted ourselves on the open verge of a rural highway near the Alabama Florida border with our thumbs hanging out. Nobody had been along for a while. I was looking one way up the highway and when I glanced back, he had just vanished into thin air! I later found out that he’d seen what I hadn’t; a cop’s cruiser came up alongside with its lights on. The cop got out, hands on hip (and gun), “Don’t you know that it is illegal in this state to hitch-hike along the highway?”! I reached for the only two cards I had available; I played dumb and I played foreign. When he asked me for ID all I had was my British passport – that did the trick; he let me off with a warning. The guy travelling with me had dived into the ditch, he only reappeared when the cop had gone.

Wado in New Orleans?

I spent quite a lot of time in New Orleans. Amazingly, by browsing the Yellow Pages I found a Wado Dojo in Metairie New Orleans, and one run by a Japanese Sensei, Takizawa Sensei 6th Dan. This was so rare in the USA; Wado is very much a minority style. If you want Shotokan there are so many karate schools to choose from, one on every street corner, but Wado is as rare as hen’s teeth.