society

Personal Security and Society, a Different Perspective.

On the back of the earlier blog posts about self-protection, I thought I would try and look at the bigger picture; particularly as it relates to society.

While I have no qualifications in sociology, criminology or demography I want to present some different ways of looking at things.

The main thrust of this post will be to put forward a series of models that may well clarify a few points and maybe explode a few myths. I will back this up with examples from various sources.

A few basics.

It goes without saying that the reasons for our success as a species is our ability to collaborate, communicate and work as a group to get stuff done with the minimum of friction [1].

To do this you need agreed sets of rules, which over time solidify into laws that we all have to agree to abide by if we want to live within our tribe/society.

And then there are whole swathes of unwritten social nuances which oil the wheels and involve social protocols, good manners, respectful behaviour and not giving in to the destructive, selfish aspects of our basic impulses. We rein ourselves in because we are mindful of the impact of our behaviour on those around us and how that affects our relationships and status in the group. For humans this is incredibly complex, at both the formal/legal level and the more fluid, unwritten domain.

The Framework.

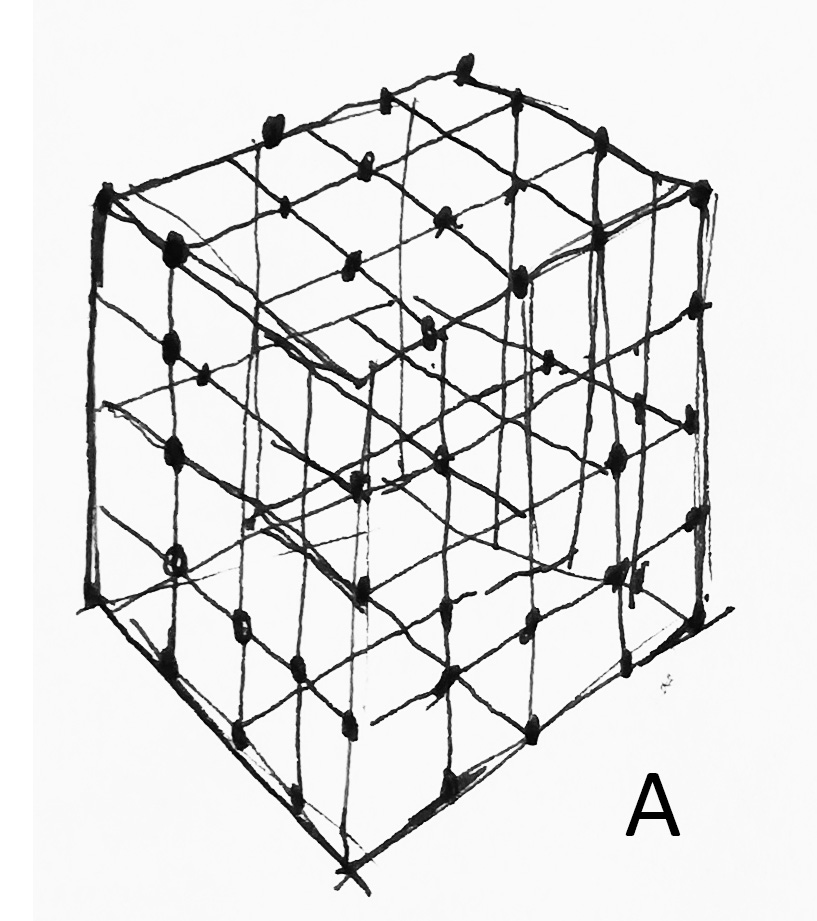

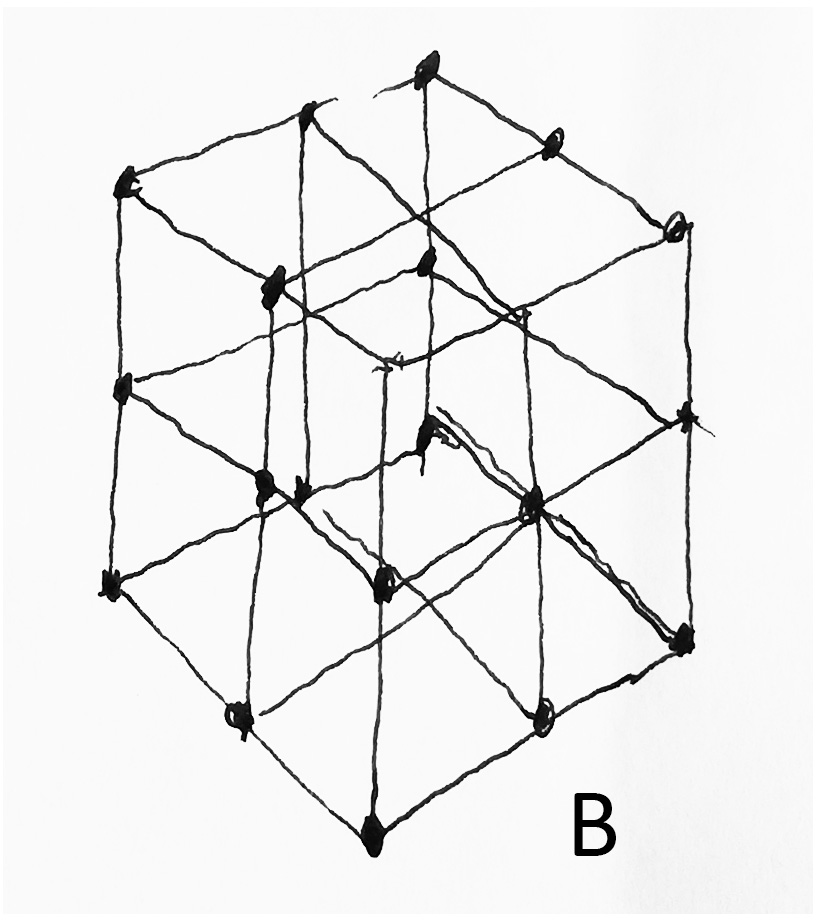

In my mind’s eye I see this as a framework. For me society is like a complex cuboid mesh, of which the strands that hold it together are both our guidelines and our constraints.

Young children grow learning to gradually adopt and navigate this framework. In their very early development it is the parents who construct and manage a world for the child that balances their needs and wants (and freedom of personal expression) and steers them towards what society expects of them.

Gradually these young children become civilised and the process continues to unfold all the way through from their home life to their schooling.

They are expected to create and navigate friendships, as well as stay within the gridlines of first; nursery, then junior school, secondary school and ever onwards. All of these institutions have a secure and complicated framework, which needs to be navigated if they are to survive and thrive. It can be disastrous for a child to fail in this responsibility (for whatever reasons), if they do, they risk being unpopular, ostracised, seen as literally an ‘outsider’ (outside ‘the grid’), which, if left unchecked or unsupported, can breed bitterness and resentment, where any perceived faults are projected outwards onto the big bad world and the people who inhabit it. In its most extreme example, it can lead to events like the Columbine High School shootings of 1999. [2]

Schools as the archetype of ‘the Grid’.

From my experience schools are typical and easily observable examples of this complex gridded cube.

I have seen this first-hand; particularly over the last three years, as a career turn has taken me inside over twenty UK secondary schools, where I have been able to observe them up-close and across all levels.

The ‘framework’ in schools is so very obvious, it even exists as a physical reality – look at the way architects, past and present, design schools. It is manifest in the box-like rooms all stacked on top of each other, connected by corridors and stairwells; even the outdoor spaces tend to be designed to constrict and control; the imagery of the grid is everywhere.

In the last ten years the physical structure of schools has become even more boxed-in; often for what is seen as very good reasons, reasons of ‘safeguarding’ and ‘well-being’, but you have to wonder, has the world become so much more of a dangerous place?

In an ever-escalating arms race of ‘security’, how big is the threat? Does it warrant the explosion of things like; key-coded exterior security gates and fences (are they to keep people out, or to keep people in?); doorways between corridors having to have swipe-card entries; everyone forced to wear lanyards with ID pictures, and (I kid you not) even lock-down zones with metal shutters that grind-down on the press of a panic button, and metal-detector gateways! [3] I have seen all of these.

You have to ask yourself, is this care and kindness geared towards the well-being of children, or is it thinly disguised paranoia that further feeds into the anxiety of young people? What messages are we giving them?

Within the constraints of this tight and complex mesh we are hoping that young people will be able to experience some freedoms and some elements of self-expression, where they can carve out their own unique identity (which, in the UK, is somewhat negated by the contradiction and oddity of the enforced school uniform![4]) I am sure that self-expression happens, but only in the gaps between the gridlines.

Where does the responsibility lie?

It seems to me that headteachers and governors are engaged in a Top Trumps game of who can outdo who in the personal security/safeguarding checklist. I just don’t think they have thought it through.

Safety in the wider world.

What happens to young people when school is no longer part of their lives?

One could suppose that as they have reached adult status the grid is a more open structure, certainly compared to schools.

It might be worth considering the example of the recent red flags that have gone up in UK universities where the apparent slackening of the grid has brought about what seems to be an epidemic of sexual predators – what is the truth behind the reported stories? Why has it been proposed that undergraduates have to have ‘consent training’ etc? [5] Is this a failure of the system, or an inevitable malaise unwittingly constructed by the system itself?

On top of this you have to ask yourself, do these young people have everything they need to survive and thrive, to navigate the bigger open-mesh of society and stay out of harm’s way? Has their education and upbringing given them the necessary tools?

They seem to lurch forward into the adult world with their parent’s words of warning ringing in their ears; but the irony for parents is that a mother’s advice to her teenage daughter as to how to stay safe on a Friday night out with friends is often based on what it was like in the 1990’s, so unless she’s got a time machine, it’s not going to be very helpful. The world changes at a phenomenal rate.

Not all grids are the same.

The societal structures (the grid patterns) are not the same all over the world; yes, they deal with the same basic issues of safety and rules but, for example, the gridlines in Birmingham UK are very different from Tijuana Mexico. (Or even Sarasota Florida).

A cautionary tale about grids.

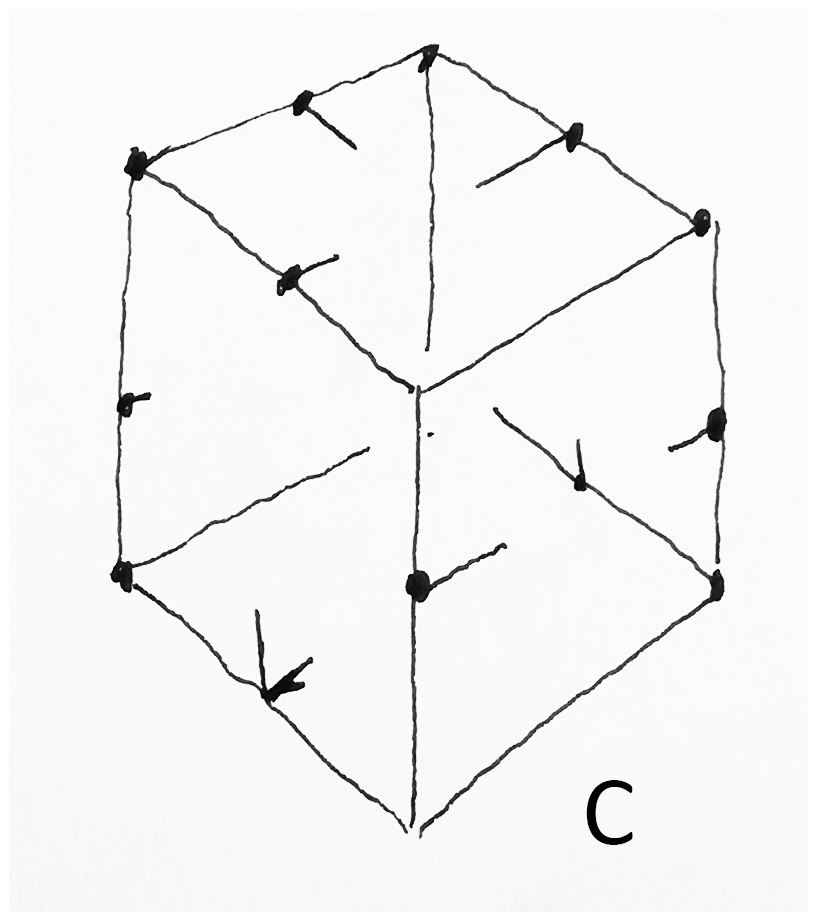

In 2011 two young British men, James Cooper 25 and James Kouzaris 24, while visiting Mr Cooper’s parents in Sarasota Florida decided to cut out on their own after an evening meal out. They were more than a little drunk, and wandered into a run-down part of Sarasota, a place called Newtown. It appears that Newtown is where the gridlines run out of road.

To cut a long story short, Cooper and Kouzaris were found dead at the side of the road. They had been shot by local boy Shawn Tyson 17, there was no sign of robbery, they both had wallets with money and phones; they just strayed into a blind spot on the grid, one which the locals of Sarasota and Newtown would have surely known about. [6]

This scenario would be unlikely to play out the same way if they were stumbling around Surbiton or Guildford at two in the morning, because they’d recognise the situation, understand their options and be able to navigate the gridlines that were available to them, while calculating the potential of threat or risks inherent to that particular scenario.

Sadly, it is unlikely that any amount of martial arts or hands-on self-defence training would have saved James Cooper and James Kouzaris.

Final word on terrorist threats.

This is a classic case of ‘head says one thing, but heart says another’, but statistically you’d have to be pretty unlucky to get caught up in a terrorist attack in the UK. Yuval Noah Harari the Israeli historian describes terrorism as ‘a puny matter’ when compared to what happens in warfare. It is essentially all spectacle and theatre designed to stoke up fear, and it does, just think about the example of the emotional and human after-effects of the Manchester bombing in 2017.

Essentially, governments and media do the terrorist’s work for them, they supply the oxygen to these combustible situations, and unintentionally become the recruiting sergeants for the next generation of terrorists through ill-thought out knee-jerk reactions. But, as they know, you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t.

Read Yuval Noah Harari’s piece in the Guardian, for a good description of how this works at a rational level.

Keep safe.

Tim Shaw

[1] As individuals in the animal kingdom we make pretty lousy predators; we are not particularly strong, agile or bulky to survive on our own without the employment of weaponry, and even then we have to operate in packs to achieve any level of success.

[2] Columbine High School Shootings https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbine_High_School_massacre

[3] Most schools I have visited have ‘lock-down procedures’, some have interior door wedges with the fear of the possibility of an ‘active shooter’, and this is the UK not the USA. The UK has only ever experienced three school shootings and all of the casualties (bar 1) occurred in just one incident. Compare that to the USA, where between the year 1999 and 2012 there have been 31 school shootings.

[4] Radical educationalist professor Guy Claxton said that schools tend to be constructed on one of two models; the are either ‘monasteries’ or ‘factories’. ‘Monasteries’ have; authorities in gowns/robes with other robes/uniforms for novices and are based upon some vague notion of revelation, with a massive worship of ‘tradition’. While ‘factories’ have bells to end shifts and have the intention of turning out identical little ‘products’ and are judged by quality controllers (Ofsted, Performance management etc), they won’t admit it but they are really exam factories. I know this because for a long time I worked in a factory that was built on the ruins of a monastery.

[5] Consent training and even ‘Good Lad workshops’ in universities and colleges. See this link from the University of Cambridge https://www.breakingthesilence.cam.ac.uk/training-and-events/training-students

[6] Murder in Florida, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-17479559