History

Sample – Part 12, Early days in Leeds.

1978 through to 1981. Undergraduate years at Leeds Polytechnic, studying graphic design.

Living in Headingley (and later Harehills) and taking over the running of the Leeds YMCA Wado Dojo under the authority of Suzuki Sensei’s UKKW.

Post Mansfield and my arrival in Leeds had given my karate full licence to develop in its own way – of course within the constraints of mainstream Wado and very much marching to the UKKW/Suzuki drum. In my own head I reckoned that the apprenticeship had been served.

By that time I had pretty much decided that competition karate was not going to give me what I needed. Although I did enter competitions in my early years at Leeds I became disillusioned with how things were run (e.g. Carlisle, Huddersfield, the Nationals). I had no desire to build a team to rival the top teams of the day, it just wasn’t part of my agenda (the same Leeds Dojo became famous only after my departure, after Keith Walker took over and embraced the competition world with his characteristic energy and enthusiasm).

Although I was building a Dojo, it was all geared towards ‘Project Me’. I think I must have figured that if I was going to be running the club with some authority as a twenty-year-old, I had better make sure that I could walk the walk.

Supplementary Training.

For me it was split between Dojo time and supplementary training time; and it was in this supplementary training that I became quite creative; basically, I was willing to try anything.

I started off living in student halls of residence at Beckett Park, Headingley, north of the city centre. While I was there, I gained permission to train in the weights room of the PE college, Carnegie, which was always interesting because you never knew who was going to walk through the door. I hardly saw any of the rugby set in there; the only heavy lifting they were interested in was in the Union bar. It became a bit of a joke, the piss-head rugby crowd were only ever seen in the evening, while the serious athletes were only ever seen at 6am for their morning run – always an early night for those people.

In the weights gym were specialist athletes; like the canoeists, guys with massive shoulders, yet tiny skinny legs. And throwers; lots of throwers, javelin, discus and shot; many of them trained by Wilf Paish, a small man who would drift in and out of the gym and never seemed to smile. Paish had his finest hour in the 1984 Olympics as mentor to Tessa Sanderson and Fatima Whitbread.

I initially tried to connect with the Shotokan group on the campus, but the Shotokan big cheese must have seen me as too much of an outsider and let me know that I just wasn’t welcome. He told me to go and train in a corner; as a result this was a very short-lived experience.

Always looking for a new opportunity to train, I used the gym equipment at the Leeds Playhouse when I was in the city centre, sometimes lunchtimes, sometimes early evenings. This was the ‘Multi-gym’ type equipment, but it was very manageable and I was always able to get a reasonable workout.

I even trained with the Leeds University boxing club, however, it interfered too much with my technique. I didn’t let the trainer know I’d done anything before; he liked how I used my waist, but it wasn’t to be; but it was worth a punt anyway.

On top of this I did an awful lot of running. The Headingley parkland and running track were perfect for that, and with all those PE student-types around, it just seemed to be the done-thing, although I always found the early morning runs a real chore.

Lifestyle.

I never lost the habit of walking everywhere; averaging four times a day from Headingley to the city centre site, back and forth; two miles each way. I enjoyed the walking, then, as now, it gave lots of time for thinking and it never felt like a hardship.

The few times I took the bus I always felt resentful, this was magnified by the lousy attitude of many of the bus drivers, who seemed to think that passengers were an inconvenience to their working day. They hated having to give change and were brutal on the brakes when they realised that people were precariously balanced stuffed into the aisles because the seats were all taken; a quick stamp on the brake pedal and people would tumble like skittles! I suppose it gave them some fun in a working day.

As I didn’t drive at that time, everything was on foot; I never saw the inside of a taxi, they were just too expensive.

Parties and events were just word of mouth, an address, a name, or sometimes a crudely printed ticket with the date and time on it. Pre-Internet days meant holding information and a complex map of the city in your head, and any networking seem to operate at the same telepathic level as Aboriginal ‘Song Lines’, we just ‘knew’ where people were liable to be at any point on any given weekend night; spookily accurate in its psychic predictions.

The Leeds Dojo.

Gradually I had picked up a small group of karate students who were all about the same age as me; some were college kids from various courses. This enabled me to really start to pump the official twice weekly Dojo sessions at the YMCA in the city centre.

I don’t for a minute think that we were very technical – certainly not by today’s standards. We used to joke that half of the class time was dedicated to calisthenics; a bit of an exaggeration, but not far off. After I’d left Leeds, Keith Walker had taken over the Dojo; as he’d started with me as a teenager, he very much followed the tradition I had established, and, a visitor from North Yorkshire, a female karate-ka who trained at the Settle Dojo, commented that when she went to train in Leeds (post 1982) Keith had put her through a session that was mostly boot-camp callisthenics. But, to his credit, he soon found his own way of doing things.

But, being honest, a lot of the content of the training was for me; it sounds a bit selfish but my thinking was that if the students benefitted from it then all well and good. In those early days, I set the pace, I directed the exercises and I enjoyed devising new ways to work the body. We may not have been terrifically technical martial artists but we were really fit.

Eventually, twice a week was not enough for me.

The YMCA were quite happy for us to book the training space for times when things were quiet; so early Friday evening was an additional class; about three hours of extra training. In the first part of the session it was often just me and young Keith Walker and then others turned up as the evening went on.

Saturday mornings at the YMCA.

But the most enjoyable session was the Saturday morning class.

Because nobody wanted the basement gym at the YMCA on Saturday morning, we grabbed it as an extra slot. Although, living a student lifestyle, training on a Saturday morning was a bit of a stretch. It developed into one of our most creative and free-form sessions, and I think those who took part really enjoyed the buzz.

The Saturday class was for two hours. It always started with about 45 minutes of kata, though this was a token, almost a warm up.

We then went into crazy sets of relay runs (it was a long narrow gym) punctuated with circuit training-style intervals; squats, press-ups and every exercise I could throw into the mix. By the time we’d got to the end of that we were a sweaty mess and, crucially, well warmed up for the sparring. This was the ‘light sparring’ I had ‘borrowed’ from the Wolverhampton team. It always started out in the right spirit, but the more we got into it the heavier it got, but nobody seemed to care, it was a total adrenalin rush, and, because we all trusted each other, we knew how to push each other’s boundaries; high energy, yes, but full spirited.

The bonus of the Saturday morning was that we had access to the most wonderful hot water showers after training. Rinsing off the sweat with muscles feeling like mush, the euphoria after the training was better than any massage. You could have poured me into a bucket.

On many occasions the Saturday morning training was the prelude to another bigger training session in the afternoon. We would often grab a quick lunch at the YMCA cafeteria and then catch a train from Leeds to Doncaster to train for a further two or three hours with either a Japanese Sensei or another guest instructor at the Doncaster Dojo, also allied to the UKKW.

This arrangement led to some interesting and intense Saturdays.

An ‘apex’, and not untypical weekend for us, was probably:

Friday; three hours training.

Then leave your sports bag and sweaty gi in a left luggage locker in the railways station.

Go out on a heavy night, including clubbing till about 2am.

Crawl into bed, about 3am.

Up early Saturday, collect the sports bag from the station.

Two hours of hard work in the YMCA gym in a stinky, sweaty gi; no chance to recover.

To Leeds station to catch a train to Doncaster, more training.

Back into Leeds for whatever the night offered; phew!

We didn’t congratulate ourselves that we were doing anything unique; we had nothing to compare it to; it was just what it was, we just plunged in, we had the energy to do it and youth was on our side. It is only in retrospect that I realise how bonkers it was. But, it was really about being young and pushing at any boundaries we could find.

A training diary from the time details how I would sometimes clock up twenty hours a week of training in various forms.

It is often commented on that youth is wasted on the young; I am sure that in those days we were convinced we were indestructible. I suffered relatively few injuries; a niggling lower back problem, a broken toe, broken nose, various hand injuries (thumbs wrenched back) and an unfortunate and very stupid stab injury to my thigh, to which I still have the scar, which (typical of me) I had bandaged up and trained through – because I was indestructible and would let nothing stop me, and hence the stitches wouldn’t hold and the wound opened up and now I carry a bigger and uglier scar than I needed to – fool that I am. (The course on that day was a squad training session under the then England coach Eddie Cox).

Influences and opportunities.

But what about input? Where was I getting my influences from, how was I able to develop?

So much must be credited to the initiative and enthusiasm of the Genery family who ran the Doncaster Dojo. They kept us well-informed about courses they were hosting and never failed to invite us. All of the main Japanese Sensei were invited to run courses and gradings at the Doncaster Judo club; Suzuki Sensei, Shiomitsu, Nishimura, Sugasawa, Sakagami as well as courses with England coach Eddie Cox, Charles Longdon-Hughes and world champion Jeoff Thompson. Add to that the big UKKW courses, Winter and Summer and some particularly iconic courses organised in places like Sheffield and Newcastle; there was so much happening. It is often assumed that the London scene for Wado karate was where it was all happening, but Suzuki Sensei and the other Japanese Sensei were encouraged to go all over the country and the demand was there. It must have been a good way of making a living as there was never a course that was unsupported, and that was quite something in an age that was pre-Internet. All communications took place through mail and phone calls. But, for me, living as a student in Leeds, we didn’t have a phone and had to make any vital calls through payphones, so it was all word of mouth.

As I worked on my body and predominantly my fitness level I probably undervalued the technical world. Not that I taught or practised sloppy techniques; I was very exacting in refining my own skills, but only really to the demands of the time. I had been well-tutored in the syllabus book and knew what was required to pass gradings and perform a fast and sharp kata; but there were other fish that needed frying.

Fight training.

In retrospect I enjoyed exploring creativity through fighting. Sparring was a crucible for me, as I chased ideas and explored new emphasis. I remember that at one time I got really excited about rhythm and setting up tempo patterns and then breaking them; a kind of ‘leading’, a disruptive interplay.

We tried to engage with contact work, but we were always short of equipment – I think that must have been where the boxing experiment happened.

It must be said that all of this did not happen in a vacuum. We developed some useful contacts through other martial artists, other karate styles. We met some of them through competitions; although, as I have said, our competition experiences were not always fruitful.

Other courses.

I attended most of the major courses and encouraged my students to do the same. I think I only missed the 1979 summer course, a landmark course because this was Sugasawa Sensei’s first summer course in the UK. I had seen him before at the 1978 Nationals, with moustache and long hair; but the 79 summer course changed all of that for him, as it was there that he reverted back to the shaven-headed look he’d had in Japan and has subsequently stuck with ever since.

The summer and winter courses from the Leeds days followed the same pattern as previous years; though the venue of the summer course changed to Great Yarmouth and then Torquay.

But, to return the focus to the training.

These courses were marked by their large numbers. Nowadays big courses across Wado organisations are boosted by huge contingents from abroad; this was not the case in the late 70’s and early 80’s, although the winter courses did tend to attract some Scandinavians and a few Dutch. The attendees were primarily UK-based and it was good for networking, and to train with different partners. Which in itself was a bit of a lottery; you could get some really outstanding, hardworking partners or some that were either lazy (too much wanting to talk about or analyse what we were working on) or some that were just clueless. Over the years I did partner Japanese Sensei who were there for the training; Fukazawa Hiroji was new to the Suzuki way of doing things and when I partnered him he asked me to teach him the Suzuki Ohyo Gumite, which I was happy to do. (In later years I partnered Tomiyama Keiji of Shito Ryu on a large course in Guildford; a real pleasure.). These were all great learning experiences.

Grading for 2nd Dan.

I took my 2nd Dan on the Summer Course in Great Yarmouth in 1980. There were a clutch of prospective 1st Dans, and the only ones above that were myself for 2nd Dan; one of a bunch of brothers who had emigrated to Australia for 3rd Dan, and another British emigree from Sweden who was going for 4th Dan; which made fighting all the more interesting. The most senior, the Swedish/English guy had a tough time in the fighting and the Australian gave him a real drubbing, I felt quite sorry for him, he never really got started, the Aussie was all over him like a rash. Then came the time for me to fight Mr Sweden, but he’d had all the fight knocked out of him; so, it was a bit of a non-event. Then I had to spar with the Australian… I admit it here, it was a tough fight, I went with the idea that attack was the best form of defence, I was definitely outclassed, it was almost impossible to stifle his aggression, but I felt that I held my own, I certainly didn’t disgrace myself – one of my most memorable fights.

Suzuki Sensei.

On these courses the majority of my time was under Suzuki Sensei. He insisted on taking the black belts for himself, as befitting of the senior man. Shiomitsu and Sakagami had to be content with switching the brown and green belts between themselves.

Suzuki Sensei was gruff in manner and thought nothing of kicking your leg from under you and growling at you if it wasn’t up to his measure. He also had no restraint in showing his amusement when someone screwed up. His humour had a cruel side to it. He had a favoured take-down which involved grasping your collar from the back and pulling you backwards at great speed. Tokaido gis at that time had a particular weakness; although they were expensive, they used to tear at the back of the collar, near the shoulder. I think he knew this and when he needed to demonstrate the take-down I’m sure he looked for the Tokaido label, and, sure enough, ‘rip!!’ an expensive gi top split all the way down, and he would just walk away chuckling to himself.

When Suzuki Sensei was teaching kata it was all ‘Ichi, Ni, San, Shi…’ but when Shiomitsu taught kata he would start out like that and then become impatient and say, ‘practice by yourself’. I actually found this quite useful as I could really dig into repetitions and try to get under the skin of what I was doing, with the added bonus of Japanese Sensei prowling round to correct your form and maybe field questions – although the ‘fielding of questions’ was very much a later development, Suzuki Sensei did not encourage questions.

Suzuki taught by physical example; ‘like this!’ he would say, and snap sharply into position. He was very ‘hands-on’ and demanded that you mirror his moves; he almost wanted you to ‘be him’, which was a challenge for me as we were physically quite different. I make no bones about it and stick by my theory that karate was designed by shorter guys, for shorter guys. I first realised this through experiencing Suzuki’s physicality, but it was further reinforced by having to train alongside Clive Wright and Frank Johnson. These two were physical carbon copies of each other body-wise. Quite short and light in build, closer to the Suzuki ideal. I remember training alongside Clive in Yarmouth and being puzzled as to how we were both doing the same move to the same count but he was getting to the end of the motion half a beat before I was? And then I realised what the answer was, ‘short levers’; because of my limb length being longer than Clive’s (or Frank’s) I had to cover twenty inches of distance to their twelve! No wonder I was behind!

I have often pondered this conundrum; the challenge for the taller person is to aim for the same speed as the shorter person, at the same time being aware that with the longer levers there is going to be a bigger challenge to move as an integrated whole – put simply; the ends of the limbs may have the advantage of creating a longer reach but this leads to the extreme ends of the movement being significantly divorced from the body’s central core; and it is this relationship that is integral to efficient movement in Wado.

Training methods and instruction.

On these summer and winter courses there was still the emphasis on going up and down in lines; which is a very efficient way of managing the large numbers. You would think that it was very easy to get lost in the crowd, but there were so many Japanese instructors to oversee proceedings that you always felt eyes upon you. But I am sure that these large numbers hindered the opportunity for the more bespoke coaching that is needed to progress – particularly post-Dan grade. I can’t think of any course that I went on in those years where the numbers were so few that you were able to enjoy a unique access to Japanese instruction. The only instances that came close was when Sakagami Sensei was teaching at the Doncaster Dojo; but this coaching didn’t happen in the Dojo, it happened in the changing rooms afterwards. Sakagami on his own was always friendly and talkative, though always earnest and enthusiastic, once you got him on a favoured theme. But in those changing room chats he used to get carried away and we were stuck in there for ages; so much so that the organisers seemed to be frustrated in their efforts to clear up and lock up. He just went on and on, but it was so interesting and so informative.

Tim Shaw

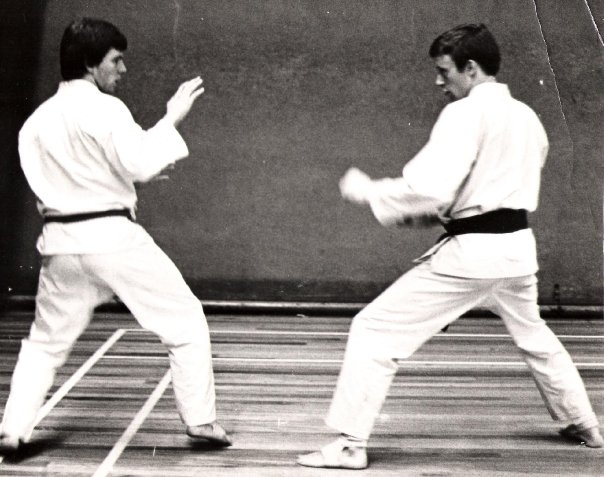

Featured image: Mark Harland and Tim Shaw in the Leeds YMCA basement gym, circa 1979.

A different take on Martial Arts Media and History.

Random reading during lock-down lead me back to a theme that had interested me for some time. In the past I had picked up a number of books on the history of the martial arts in the west. (I will give a list at the end of this post if anyone is interested).

What always intrigued me was the ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions. I was particularly interested in the civilian arts, how they were developed, how they were taught and how they were commodified.

This is a complex story but I will give a couple of examples that surprised me, and sometimes amused me.

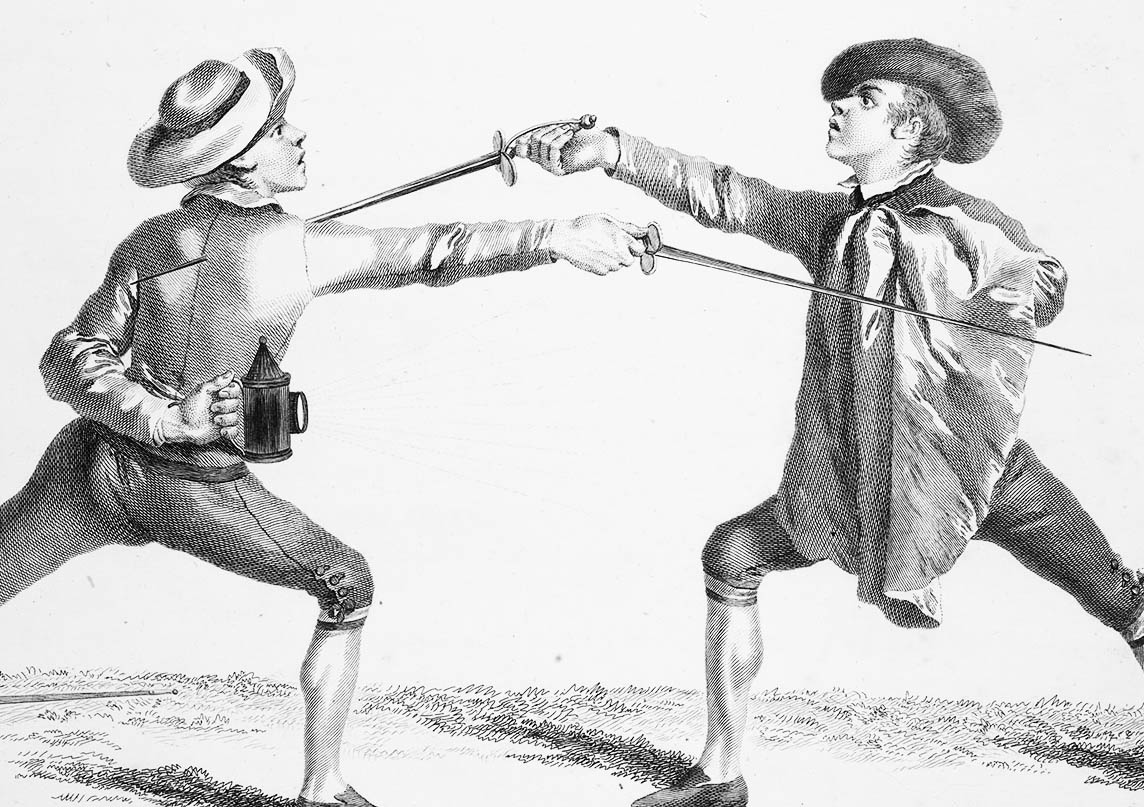

I learned that historically the English did what the English are always prone to doing, i.e. despising the foreigners and always holding themselves up as the best. If you are interested read up on George Silver, whose book ‘Paradoxes of Defence’ written in 1599 took a swipe at the cowardly foreigners use of the rapier to stab with the pointy end instead of the slashing action of the ‘noble’ English backsword. The Italians and the French bore the brunt of Silver’s ire and he aggressively sought to make his point stick – literally. He had a hatred for immigrant Italian fencing masters, particularly Rocco Bonetti and Vincentio Saviolo. He challenged Saviolo to a duel, but Saviolo failed to turn up, which caused George Silver to crow about his superiority to anyone who would listen.

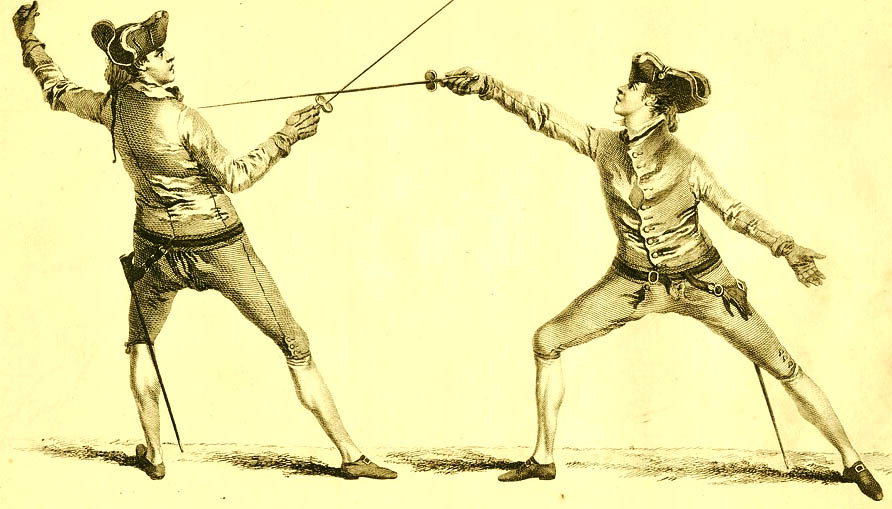

Fast forward nearly 200 years and the fencing master is still in demand. There was a market for slick Italian and French ‘masters’. Many of them taught horsemanship and, surprisingly, dancing (thus proving an observation I made in an earlier blogpost; ‘a man who can’t dance has got no business fighting’). The demand did not come from the hoi polloi, the proles – no, it came from the aristocrats, and for good practical reasoning.

From the 16th century onwards the idea of the ‘Grand Tour’ was all the rage. Wealthy young bucks were sent abroad to widen their horizons and soak in the classical antiquities around Europe and the Mediterranean. Although there was some effort made to chaperone these entitled and indulged young men (almost exclusively men) there was an expectation of expanding not just their minds but their… worldliness. This often resulted in an awful lot of bad behaviour (see, one of my particular heroes, Lord George Gordon Byron, 6th Lord Byron). Unfortunately, quite a number of these heirs came significantly unstuck. Sometimes whole fortunes were lost through gambling, or they fell under a robber’s blade or some equally dastardly misfortune.

Hence preparation for the ‘Tour’ was deemed necessary, and not just preparation of the mind, but the skills of defence, and often of fighting dirty. It was here that masters like Bonetti, Saviolo and in the 18th century the wonderful Domenico Angelo (more of him later) came in. These masters were paid well to teach sword and rapier, left-handed dagger and, intriguingly, skills like ‘cloak and lantern’; put simply, the cloak was used for defence and sometimes ensnarement, and the directed light from the lantern was used to dazzle or temporarily blind an opponent to allow the use of the sword or left-handed dagger.

But to return to Domenico Angelo (1717 – 1802). Angelo was sponsored by the Earl of Pembroke and later the dowager Princess of Wales; this patronage did him huge favours and boosted his reputation enormously. He was astute enough to build a business from his arts and turn it into a dynasty, three generations of Angelo’s thrived in their property in Soho Square and other premises. Angelo was an excellent example of early marketing, publishing a fencing instruction book, L’École des armes”, in 1763. He is said to have single-handedly turned the art of war into sport and health promotion; where have we heard this before?

But it is the issue of publication that intrigues me. This dissemination of martial skills through whatever means possible had been around for hundreds of years. There are medieval European fencing manuals still in existence. These are pored over by enthusiasts, researched both intellectually and physically by obsessives who enjoy nothing better than swinging two-handed blades at each other in full armour – the medieval version of Fight Club.

The manuals served a number of purposes. Expert in the field John Clements proposed eight possible motives for the creation of these books, all of which have resonance with recent discussion regarding how we access and archive martial arts material in the 21st century:

- To preserve the instructor’s teachings.

- As a private study guide for selected students.

- As a primer or reminder for students when not in class.

- To impress nobles with their knowledge as a professional instructor in order to gain patronage.

- At the behest of an interested sovereign or aristocratic supporter of the art.

- To promote themselves and teachers of the craft and acquire new students.

- To publicly declare their skills or dispute the teachings of other masters.

- As a means of acquiring a pension through recognition or appreciation of years of service and dedication.

What motivated medieval masters and swords masters right up until recent times to publish and present is pretty much the same as it is now. If we look at Japanese martial arts a similar pattern can be seen.

From the ‘patronage’ perspective I will cite a few examples:

The Yagyu dynasty of swordsmen from the 17th century, sponsored by the Tokugawa clan.

The 20th century sponsorship of Ueshiba Morihei founder of Aikido by various well-connected individuals.

Also Funakoshi Gichin, who worked hard to establish karate on mainland Japan in the 1920’s, something he could not have done without courting the right kind of sponsorship.

In the far east books and ‘master texts’ on martial arts have a long history; whether it is the ‘Bubishi’ or ‘Karate-Do Kyohan’. But they are never all-encompassing; it has to be said that it’s a virtual impossibility to give the complete body of information through the printed or written medium.

In line with the above list these publications fall into various categories; crib books, catalogues, visual cues, or in the case of Koryu Densho, transmission scrolls with opaque lists meant to be decoded only by the initiated. What surprises me, in this age of digital curation, archiving and future-proofing is that the old technology of printed paper versions have held up so remarkably well.

Some martial arts are better supplied by these various types of repositories. If your fighting method is comprised of only a handful of techniques, as can be found in some military manuals, then all you need is a few diagrams and a basic description. But if your art is more refined, with nuances and subtleties it is impossible to put these across in anything other than face to face encounters. The founder of Wado Ryu karate Otsuka Hironori is said to have expressed his frustration with trying to put his ideas into printed form. As this extract from a 1986 interview with Horikawa Chieko, widow of Daito Ryu master Horikawa Kodo tells us;

“On one occasion… an expert in Wado-ryu karate by the name of Hironori Otsuka happened to visit the dojo. He and Horikawa got on quite well. He was a wonderful person, and very strict about technique. He was talking with Horikawa and he said, “I’ll never write a book either” for example, there are many ways to put out one’s hand, but in a book all that can be conveyed is the phrase “put out your hand”, which misses all the subtleties. Both he and Horikawa agreed that techniques cannot be expressed in books or in words.”*

This is a discussion that could go on and on, and it is clear that the market place hasn’t so much become crowded as to have almost decamped altogether to the online world, where clamoring voices and slick marketing compete for our attention, almost to the point of overload.

A debate as to how this could all work out in the 21st century, with the involvement of new technology, can be found in an excellent slim publication by Matt Stait and Kai Morgan called ‘Online Martial Arts. Evolution or Extinction’. Ironically available in printed form and download from Amazon.

*Pranin, Stanley, ‘Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu’ 1996.

Recommended reading:

‘By the Sword’ Richard Cohen 2002.

‘The English Master of Arms’, J. D. Aylward, 1956.

Tim Shaw