books

Books for martial artists. Part 1. Lost in translation.

A two-part martial arts journey into where ‘extra reading’ can take you.

It’s only natural for us to want to boost our martial arts learning by reading around the subject, or tracking down published material that in some way gives us hints as to how to focus and direct our lives in a manner worthy of the Budo ideal.

In a previous blog post (‘Why are there so few books on Wado karate?’) I was puzzling over the fact that there are very few written sources specifically dedicated to Wado. But what about the general reader who might want to dig into history, culture or how things operate in other systems?

Publications originating in the far east.

Like everyone else, I have found myself drawn towards written material from Japan or China, with a particular fascination with the really early stuff. But of course, I have had to make do with English translations.

However, experience has taught me to be wary of these translations, as so much can be lost or completely twisted out of shape.

Here are the main problems:

- Bad translations either written with the translator’s bias, a political agenda, the translator’s preconceived ideas, the translator looking at the text through modern lenses, the translator being a non-martial artist, thus not understanding specialised language, etc.

- Misunderstandings; e.g. kanji or old style Chinese characters being badly copied [1], or so outdated as to be almost unintelligible without HIGHLY specialised knowledge.

- Things taken out of context, e.g. their historical context, or cultural context.

- Deliberate obfuscation – text written in a way that only the initiated can understand them.

Of all of the above I think it is the ‘taken out of context’ that is the biggest error. The further back in history you go the more you encounter cultural and historical contexts that are so alien they are almost undecipherable. As a comparison, think how difficult some phrases from Shakespeare are to understand. [2]

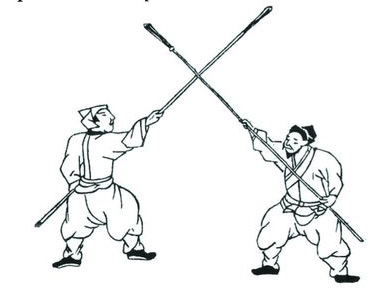

Pictures speak louder than words.

You might imagine that pictorial references, even in antiquated texts have more to offer than translations? But that also can be hugely problematic.

Here are two early martial arts examples that come to mind:

The Heiho Okugisho.

The earliest origin of parts of this martial arts book might go back as far as 1546, but really, who knows? Studies on this suggest it’s a chop-together of mostly Chinese sources that found their way to Japan and became really popular among martial arts enthusiasts in the Edo Period. It included, descriptions and drawings of techniques of spear and halberd, as well as empty-handed techniques and was eagerly devoured by aficionados and dilettantes alike and, according to one commentator, was passed around like porn mags or chicken soup recipes, with a hopeful belief that it was the real McCoy. But even with its enticing line drawings of men in antiquated Chinese dress, just about everything in it is bogus. Not to put too fine a point on it, it’s like a modern-day Photoshop fake. And still people studied it trying to tease out the ‘secrets’ hidden within and looking for the missing link of a Chinese connection to Japanese martial arts. [3]

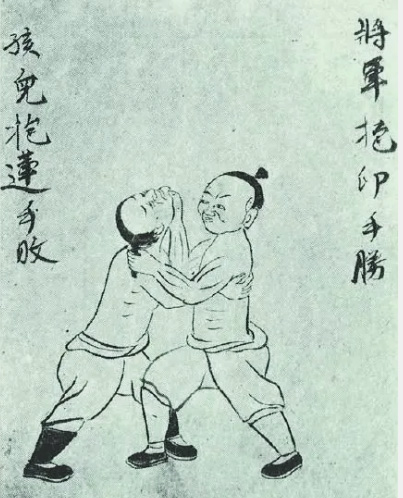

The ‘Bible of Karate – the Bubishi’.

This particular publication has a strikingly similar backstory to the Heiho Okugisho. The structure follows a comparable pattern and with the same maddening obscurities. Here is a book that was ‘kept hidden’ until around 1934 when parts of it were published in Japan. It emerged from Okinawa and so people inevitably connected it to Okinawan karate. It’s a book comprised of Chinese self-defence moves (line drawings and brief descriptions), various sections connected to herbalism and a questionable set of visual diagrams relating to ‘vital point’ striking. Much of it is written in flowery ancient Chinese characters that only the initiated have a hope of understanding.

When it was released as an English translation in 1995, I was eager to get my hands on it. Yes, it was intriguing and I studied it closely, trying to extract some kind of meaning from it. The drawings I could relate to, but any techniques I could find in them were quite basic; but really, what did I expect to find in line drawings with no meaningful accompanying text? Essentially, as a ‘how to do it manual’ it was (for me at least) a failure.

Over the last twenty-seven years more critical and well-informed eyes have examined the Bubishi and in some areas it is just not stacking up. Take for example its claim that it related to White Crane Chinese Gung Fu, and thus suggesting a clear link with Okinawan karate to a Chinese root. Apparently, according to experts in the field, White Crane has so much more to it than that, AND the ‘vital point’ diagrams look more and more like pure fantasy. [4] [5]

Here’s another one; not a book but a document:

“Itosu said…” well, did he really? And if so, what did he actually mean?

Some karate enthusiasts have eagerly brought their gaze towards an obscure, very short letter written by Okinawan karate master Itosu Anko (1832 – 1915) [6]. The letter was written to an Okinawan school board in 1902 and its intention was to explain in ten bullet points the virtues of karate training in the education system and a few basic guidelines as to how to approach training – to keep you on the right track. The letter has value by virtue of the fact it survived. In Okinawa so little was written and most of what was ended up in ashes as in 1945 the American forces had to pretty much raze large sections of the Okinawan islands to root out the resistant forces. But, as a cultural artefact Itosu’s letter is a hell of a rarity and really that is where its value comes from.

Some enthusiasts have rightly acknowledged the translation issue but have found themselves chasing after the wrong rabbit and have suggested that it is better to have a non-martial artist, non-specialist do the translation. Actually, it is that very problem that ruined Otsuka Sensei’s book for western audiences, because the English translation done by a non-martial art specialist misses out the nuances and implications of Otsuka Sensei’s carefully chosen characters.

With Itosu’s letter it is incredibly difficult to tease out anything beyond platitudes and generalisations, it’s not ‘The Da Vinci Code’ or the ‘Mayan Prophesies’, it’s a letter with a clearly defined audience in mind (the school board) and it pretty much does the job. For some people it has become a kind of manifesto, but if that is the case it is thin gruel. Yes, it is interesting, particularly as a snapshot in time and place, we can learn a lot from it as a cultural icon and there is much to gain from this window into a world long gone.

There are too many books and publications to go into in this post but I would like to put in some recommendations that particularly chimed with me and that I am prone to go back to time and time again.

- ‘The Unfettered Mind’ Takuan Soho. I have always loved this book, written some time in the 1630’s by monk/scholar Takuan Soho as a series of essays directed as guidance to the famous Yagyu clan of swords masters, teachers to the Shogun. The suggestion has always been that it was a Zen text but contemporary expert William Bodiford puts a good case that it is really a Neo-Confucian work (to me it fits far better than the contemplative approach of the Zen school of thinking).

- ‘The Tengu-Geijutsu-ron’ of Chozan Shissai (translation by Reinhard Kammer, published as ‘Zen and Confucius in the Art of Swordsmanship’). Written around 1728. Shissai expresses his ideas in a novel format and has harsh words for the swordsmen of his generation. The philosophical content and mindset come to life once you realise what he means by ‘Heart’, ‘Mind’ and ‘Life Force’ as it relates to Japanese martial culture. But there are some clever models and ideas scattered throughout the text.

- ‘The Sword and the Mind’ ‘Heiho Kaden Sho’, translation by Hiroaki Sato. The core essays date from the mid 1600’s and comprise practical guidance by the above mentioned Yagyu family. A great history section, but there is considerable content on the Mind and strategic outlook for the professional swordsman.

It won’t have escaped your attention that the above examples are all from swordsmanship, but it is my feeling that Japanese Budo/Bujutsu is well represented through the refinement of the art of the sword; particularly as it relates to the high level of psychospiritual culture that developed over many centuries and probably reached its zenith in the 17th century. The relevance of this is still present in our approach to training in modern martial arts, particularly Wado; weapon or no weapon, we carry a technical legacy that should still be with us, and we should always be trying to identify and reach towards those rarefied goals.

Conclusion.

Ultimately, reading any reliable material in and around your pet subject has to be a good thing. Understanding context, in particular, is crucial to getting under the skin and really understanding what you are doing. Many systems have depth and history and have gone through refinement and transformative processes to get where they are today. Generally speaking, reading is one of the most sure-fire ways of journeying into the cultural lineage of your system.

My view is that reading gives you glimpses of a mindset that is so very different from our own, whether it is the Itosu Letter or master Otsuka’s terse poetic axioms [7] it is clear that the time, the place and the culture inevitably wired-in ways of thinking and looking at the world that have entirely different priorities to the ones we have today. Yes, there are universal principles like justice and a desire for peace, but the societies were structured on pre-industrial almost feudal models (or were in the process of struggling to break free of those models) so it would be a mistake to simply project our views on to their writings.

In part two I intend to take a brief look at more modern examples (that may or may not be written with martial artists in mind) and look at how the west chooses to utilise eastern examples.

Tim Shaw

[1] Early text were hand copied, often generation after generation, remember, printing presses only worked well with European alphabets. Errors occurred, and then were magnified (Chinese Whispers).

[2] I have a particular fascination with the I-Ching, (said to be over 5000 years old). On my bookshelves I have five versions which I tend to compare against each other, the differences are quite startling.

[3] Reference; Ellis Amdur, ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’.

[4] See, https://whitecranegongfu.wordpress.com/2014/12/02/the-bubishi-myth/

[5] Consider the story of how Doshin So the founder of Shorinji Kempo was inspired to create his system after observing a mural painted on the wall of the Shaolin Temple, when he visited in the 1920’s and 30’s, showing Chinese and Indian monks training together. Although Shorinji Kempo history states that it was actually the spirit of training together that inspired Doshin So, not necessarily the technique. But it goes to show how pictorial imagery can inspire ideas.

[6] Itosu Anko is a very important figure in the more recent story of Okinawan karate and features at the point just before karate jumped from the islands to mainland Japan in the form of Itosu’s student Funakoshi Gichin, who was incidentally the first karate teacher of Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado Ryu. So, in some ways Itosu can be seen as the ‘grandfather’ of the Okinawan karate element contained within Wado.

[7] Master Otsuka composed short poems to express his ideas of how martial arts should function in the world. An example, “On the martial path simple brutality is not a consideration, seek rather an intense pursuit of the way that describes peace”. Source, article by Dave Lowry, ‘A Ryu by any other name’. Black Belt magazine, May 1986.

Bubishi Image credit: ‘Sepai no Kenkyu’ Mabuni Kenwa.