Philosophy

Books for martial artists. Part 2. East meets West, and West meets itself.

In this second part I want to dip a toe into the way ideas originating in the far eastern martial arts migrated to the west and then morphed into something else.

Also, whether the current brands of ‘self-help’ publications may or may not have something to offer us as martial artists.

Sun Tzu – The Art of War.

If anything can be clearly categorised as being a ‘martial arts’ book it has to be Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Said to have been written around 500 BCE, this short text contains a wealth of martial knowledge and strategy. [1] The beauty of the book is that it is broad in its application and scope, yet detailed enough to pick out examples for reflection; and it plays with the conceit of being applicable to individual combat and battles involving large numbers.

People in the west have been aware of this book for as long as there has been an interest in orientalism, and inevitably it has been appropriated by the business world. So many spin-offs telling us how Sun Tzu’s book can be applied to the cut and thrust of the high-powered boardroom -everyone is looking for an edge. Titles appeared like, ‘Art of War for Executives’, ‘Sun Tzu – Strategies for Marketing’, etc, etc.

Musashi Miyamoto – ‘The Book of Five Rings’.

Musashi’s terse book on strategy and fighting suffered a similar fate to Sun Tzu. I have mixed feelings about the Book of Five Rings. At least one Japanese Sensei I have spoken to has been puzzled about Musashi’s status, as in, ‘why this guy?’, ‘Why does this dubious character deserve so much attention, when there are so many more elevated examples… Katsu Kaishu was an amazing model, yet nobody talks about him?’.

I have seen ‘the entrepreneurs guide to the Book of Five Rings’ and others have tried to piggyback on this book of ‘wisdom’.

Musashi was a product of his age, and in terms of Darwinian principles, managed to stay alive through sheer cunning and an unorthodox approach (though, what was orthodoxy in that age is very fluid. 16th century Japan was like the wild west). Again, you have to understand the context.

A quick note on the ‘Warrior’ mentality.

Excuse me for my cynicism here but nothing grinds my gears like the overuse and appropriation of the word ‘warrior’.

As a ‘meme’ on the Internet all these ‘warrior quotes’ are guaranteed to cause me to gnash my teeth in anger and frustration.

Musashi ‘quotes’ abound (which end up as not ‘quotes’ at all, just some made up cobblers nicked from another source). [2]

Just what do people mean when they refer to ‘Warriors’ anyway? Are we talking about the modern context; the professional soldier? If so, the gulf between that model and the model presented by someone like Homer when he introduced us to Achilles and Hector, or, in Japan the stories told about Tsukahara Bokuden (1489 – 1571) [3] is just too huge a gulf to be bridged; different worlds, different mentality, different technology. Unfortunately, the romantic appeal of BEING a ‘warrior’ attracts precisely the same people who lack all the idealised and fictional attributes of so-called warriordom, a domain for fantasists and keyboard heroes. Sad, but true.

To return to books.

‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’

I know that I have mentioned in a blog post previously about Inazo Nitobe’s ‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’ book. Essentially it is a confection running an agenda, in that Nitobe wanted to build a cultural bridge between Japan and the west with a distinctly Christian bias (he was a Quaker). He created an overblown link between the romanticised ideal of medieval chivalry and an equally fictionalised picture of the ‘code of the Samurai’; as such, in a nutshell, ‘Bushido’ was a modern invention. I’m sorry, but somebody had to say it.

‘Zen in the Art of Archery’.

Although this book has been influential for some time it also suffers criticism not dissimilar to Nitobe’s book. Eugen Herrigel, wrote the book after his experiences with a Japanese Kyudo (archery) teacher, Awa Kenzo. Herrigel was teaching philosophy in Japan between 1924 to 1929, the book was published in Germany in 1948. My view is that Herrigel’s achievement in writing this very short book was that he introduced the element of spirituality linked to Japanese martial training to western thinking. Although I feel a need to offer a disclaimer here… Herrigel has taken some flak (posthumously, he died in 1955); intellectual big guns like Arthur Koestler and Gershom Scholem pointed out that in the book Herrigel was spouting ideas that came from his connections with the Nazi party.

Yamada Shoji in his book ‘Shots in the Dark’ suggests that Herrigel had got it all wrong and that the ‘Zen’ element was embroidered into the story. Yamada also tells us that conversations Herrigel had with Awa Sensei were either misunderstood or simply didn’t happen.

The title alone spawned homages to Herrigel’s book – ‘Zen and the Art of Motocycle Maintenance’ comes to mind. Also, in a previous post I mentioned ‘The Inner Game of Tennis’ by Gallwey; it was Herrigel’s book that inspired Gallwey’s thinking; so, let’s not give Eugen Herrigel too hard a time.

Western books that may be relevant.

Rick Fields books are quite interesting, one in particular. Don’t be mislead by the title (based on what I’ve said above) but ‘The Code of the Warrior – in History, Myth and Everyday Life’ is a really engaging read. Fields gives us a potted history of the urge to take up arms, from the prehistoric times through to Native American culture and even a chapter on ‘The Warrior and the Businessperson’, looking at Japanese business methods and their link to samurai mentality.

Rick Fields other books have a more spiritual dimension and tend to look dated and New Age in their outlook, (written in the 1980’s); ‘Chop Wood, Carry Water’ has a clearly Buddhist vibe with a touch of the ‘Iron John’ about it. [4]

Self Help books.

Although not specific to martial arts training the so-called ‘Self Help’ book explosion may have some useful cross-overs. I had previously written a book review for ‘The Power of Chowa – Finding Your Balance using the Japanese Wisdom of Chowa’ by Akemi Tanaka. There are other books encouraging us to lead better lives that have a base in Japanese thinking, but Tanaka’s book has a clear objective of helping people to restore a meaningful balance in their lives.

I know other martial artists I have spoken to have found certain authors useful in contributing to the spiritual side of their martial arts experience. To mention a few:

- Stephen Covey, author of ‘Seven Habits of Highly Effective People’. I haven’t read it but I did read his book, ‘Principle Centred Leadership’. My takeaway from that was how much Covey was borrowing from other sources – some stand-out examples seem to come from Taoism; but useful nevertheless.

- A raspberry from me for Richard Bandler, I am suspicious of anything from him and his followers; he is one of the originators of Neuro-linguistic programming (NLP). It is, essentially pseudoscience and latest neurological research suggests that Bandler is barking up the wrong tree.

- Following a Zenic direction, Eckhart Tolle’s descriptions of the benefits of ‘living in the Now’ are worth taking a look at (though avoid the audiobook version of ‘The Power of Now’, unless you suffer from insomnia; his voice is one continuous flat drone).

- Followers of this blog will perhaps have realised that I have a lot of time for Jordan B. Peterson; however, only three books have been published [5], but the online lectures are solid gold. Peterson has some interesting thoughts on serious martial artists, who he talks about in his references to the Jungian concept of the Shadow.

The Dark Arts.

This post would not be complete without mentioning what I have called ‘the Dark Arts’. These are almost exclusively western in origin. I am not really sure where I stand on the efficacy or even the morality of these publications, but here is a list:

- ‘The Prince’, Niccolo Machiavelli 1532. The vulpine nature of Machiavelli just oozes off every page. He was a master of deception and treachery, a minor diplomat in the Florentine Republic. ‘The Prince’ is a masterwork for anyone who wants to succeed at any cost. But you might want to wash your hands afterwards.

- ‘The Art of Worldly Wisdom’ Baltasar Gracian 1647. Similar in nature to ‘The Prince’. Gracian was a Spanish Jesuit priest. Winston Churchill was said to be inspired by this book. It is dedicated to the arts of ingratiation, deception and the cunning climb to power. Just as apt today as it was then.

- Contemporary writer Robert Greene is perhaps the inheritor of Machiavelli and Gracian; in fact, he borrows heavily and unashamedly from these sources. He initially shot to fame with his 1998 book ‘The 48 Laws of Power’. The titles of his books always suggest to me as a mandate for roguery and look to all intent and purposes like a villain’s charter, as an example; ‘The Art of Seduction’ 2001 and ‘The Laws of Human Nature’ 2018. This put me off, that, and a conversation with my barber who seemed to enjoy the salacious nature of Greene’s ‘words of wisdom’. But I listened to Greene interviewed on a podcast and my view changed. Having now read ‘The 48 Laws of Power’ I realised that Greene wrote this almost from a victim’s perspective and I saw in it mistakes I had made in my past and have since bitterly regretted. A useful and humbling experience. There is more humanity in this book than I initially assumed – but also a good measure of naked ambition and dirty dealings, if you like that sort of thing.

Clearly this is not a comprehensive list of everything out there, just things I wanted to share. I think there are many martial arts people who want to look beyond the physicality of their discipline and have an urge to find a wider meaning to their efforts – which is entirely in line with the broader scope of Budo, as envisioned by Japanese masters like Otsuka Hironori, Kano Jigoro and Ueshiba Morihei.

Follow your curiosity and enjoy your reading.

Tim Shaw

[1] The Penguin ‘Great Ideas’ edition is a mere 100 pages in length, with each page consisting of very short stanzas – a very simple read.

[2] The only time I felt inclined to use a ‘warrior based’ quote was a very apt one that I quite liked, “The nation that will insist on drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking done by cowards”. Thucydides.

[3] Bruce Lee’s ‘Fighting without fighting’ scene in ‘Enter the Dragon’ was stolen straight from stories about Tsukahara Bokuden.

[4] ‘Iron John – A Book About Men’ by Robert Bly. The author attempted to rescue the soul of masculinity, this was intended as an antidote to the excesses of feminism (well this was 1990!) but it was ridiculed and derided in all quarters as it became associated with all the ‘sweat lodge’, ‘male bonding’ razzamatazz, that might have been quite benign, although misguided, but quickly turned into something darker.

[5]. Jordan B. Peterson books; ‘Maps and Meaning’ (a demanding read), ‘Twelve Rules for Life’, (much easier to read and really relevant) and the latest book, ‘Beyond Order’, also good.

Image: ‘St Jerome in his study’ by Albrecht Dürer 1514. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Books for martial artists. Part 1. Lost in translation.

A two-part martial arts journey into where ‘extra reading’ can take you.

It’s only natural for us to want to boost our martial arts learning by reading around the subject, or tracking down published material that in some way gives us hints as to how to focus and direct our lives in a manner worthy of the Budo ideal.

In a previous blog post (‘Why are there so few books on Wado karate?’) I was puzzling over the fact that there are very few written sources specifically dedicated to Wado. But what about the general reader who might want to dig into history, culture or how things operate in other systems?

Publications originating in the far east.

Like everyone else, I have found myself drawn towards written material from Japan or China, with a particular fascination with the really early stuff. But of course, I have had to make do with English translations.

However, experience has taught me to be wary of these translations, as so much can be lost or completely twisted out of shape.

Here are the main problems:

- Bad translations either written with the translator’s bias, a political agenda, the translator’s preconceived ideas, the translator looking at the text through modern lenses, the translator being a non-martial artist, thus not understanding specialised language, etc.

- Misunderstandings; e.g. kanji or old style Chinese characters being badly copied [1], or so outdated as to be almost unintelligible without HIGHLY specialised knowledge.

- Things taken out of context, e.g. their historical context, or cultural context.

- Deliberate obfuscation – text written in a way that only the initiated can understand them.

Of all of the above I think it is the ‘taken out of context’ that is the biggest error. The further back in history you go the more you encounter cultural and historical contexts that are so alien they are almost undecipherable. As a comparison, think how difficult some phrases from Shakespeare are to understand. [2]

Pictures speak louder than words.

You might imagine that pictorial references, even in antiquated texts have more to offer than translations? But that also can be hugely problematic.

Here are two early martial arts examples that come to mind:

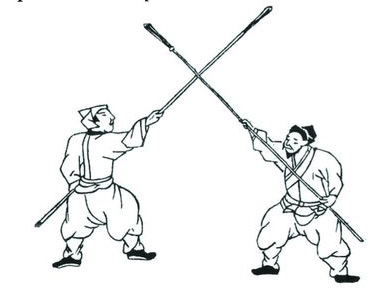

The Heiho Okugisho.

The earliest origin of parts of this martial arts book might go back as far as 1546, but really, who knows? Studies on this suggest it’s a chop-together of mostly Chinese sources that found their way to Japan and became really popular among martial arts enthusiasts in the Edo Period. It included, descriptions and drawings of techniques of spear and halberd, as well as empty-handed techniques and was eagerly devoured by aficionados and dilettantes alike and, according to one commentator, was passed around like porn mags or chicken soup recipes, with a hopeful belief that it was the real McCoy. But even with its enticing line drawings of men in antiquated Chinese dress, just about everything in it is bogus. Not to put too fine a point on it, it’s like a modern-day Photoshop fake. And still people studied it trying to tease out the ‘secrets’ hidden within and looking for the missing link of a Chinese connection to Japanese martial arts. [3]

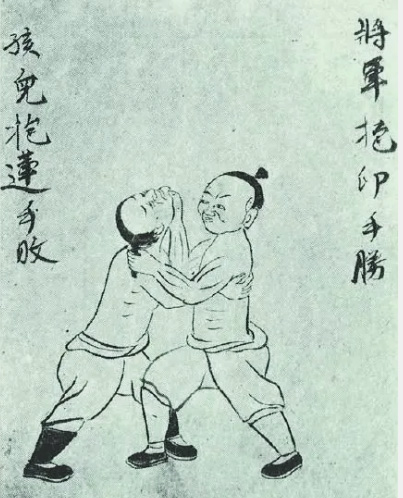

The ‘Bible of Karate – the Bubishi’.

This particular publication has a strikingly similar backstory to the Heiho Okugisho. The structure follows a comparable pattern and with the same maddening obscurities. Here is a book that was ‘kept hidden’ until around 1934 when parts of it were published in Japan. It emerged from Okinawa and so people inevitably connected it to Okinawan karate. It’s a book comprised of Chinese self-defence moves (line drawings and brief descriptions), various sections connected to herbalism and a questionable set of visual diagrams relating to ‘vital point’ striking. Much of it is written in flowery ancient Chinese characters that only the initiated have a hope of understanding.

When it was released as an English translation in 1995, I was eager to get my hands on it. Yes, it was intriguing and I studied it closely, trying to extract some kind of meaning from it. The drawings I could relate to, but any techniques I could find in them were quite basic; but really, what did I expect to find in line drawings with no meaningful accompanying text? Essentially, as a ‘how to do it manual’ it was (for me at least) a failure.

Over the last twenty-seven years more critical and well-informed eyes have examined the Bubishi and in some areas it is just not stacking up. Take for example its claim that it related to White Crane Chinese Gung Fu, and thus suggesting a clear link with Okinawan karate to a Chinese root. Apparently, according to experts in the field, White Crane has so much more to it than that, AND the ‘vital point’ diagrams look more and more like pure fantasy. [4] [5]

Here’s another one; not a book but a document:

“Itosu said…” well, did he really? And if so, what did he actually mean?

Some karate enthusiasts have eagerly brought their gaze towards an obscure, very short letter written by Okinawan karate master Itosu Anko (1832 – 1915) [6]. The letter was written to an Okinawan school board in 1902 and its intention was to explain in ten bullet points the virtues of karate training in the education system and a few basic guidelines as to how to approach training – to keep you on the right track. The letter has value by virtue of the fact it survived. In Okinawa so little was written and most of what was ended up in ashes as in 1945 the American forces had to pretty much raze large sections of the Okinawan islands to root out the resistant forces. But, as a cultural artefact Itosu’s letter is a hell of a rarity and really that is where its value comes from.

Some enthusiasts have rightly acknowledged the translation issue but have found themselves chasing after the wrong rabbit and have suggested that it is better to have a non-martial artist, non-specialist do the translation. Actually, it is that very problem that ruined Otsuka Sensei’s book for western audiences, because the English translation done by a non-martial art specialist misses out the nuances and implications of Otsuka Sensei’s carefully chosen characters.

With Itosu’s letter it is incredibly difficult to tease out anything beyond platitudes and generalisations, it’s not ‘The Da Vinci Code’ or the ‘Mayan Prophesies’, it’s a letter with a clearly defined audience in mind (the school board) and it pretty much does the job. For some people it has become a kind of manifesto, but if that is the case it is thin gruel. Yes, it is interesting, particularly as a snapshot in time and place, we can learn a lot from it as a cultural icon and there is much to gain from this window into a world long gone.

There are too many books and publications to go into in this post but I would like to put in some recommendations that particularly chimed with me and that I am prone to go back to time and time again.

- ‘The Unfettered Mind’ Takuan Soho. I have always loved this book, written some time in the 1630’s by monk/scholar Takuan Soho as a series of essays directed as guidance to the famous Yagyu clan of swords masters, teachers to the Shogun. The suggestion has always been that it was a Zen text but contemporary expert William Bodiford puts a good case that it is really a Neo-Confucian work (to me it fits far better than the contemplative approach of the Zen school of thinking).

- ‘The Tengu-Geijutsu-ron’ of Chozan Shissai (translation by Reinhard Kammer, published as ‘Zen and Confucius in the Art of Swordsmanship’). Written around 1728. Shissai expresses his ideas in a novel format and has harsh words for the swordsmen of his generation. The philosophical content and mindset come to life once you realise what he means by ‘Heart’, ‘Mind’ and ‘Life Force’ as it relates to Japanese martial culture. But there are some clever models and ideas scattered throughout the text.

- ‘The Sword and the Mind’ ‘Heiho Kaden Sho’, translation by Hiroaki Sato. The core essays date from the mid 1600’s and comprise practical guidance by the above mentioned Yagyu family. A great history section, but there is considerable content on the Mind and strategic outlook for the professional swordsman.

It won’t have escaped your attention that the above examples are all from swordsmanship, but it is my feeling that Japanese Budo/Bujutsu is well represented through the refinement of the art of the sword; particularly as it relates to the high level of psychospiritual culture that developed over many centuries and probably reached its zenith in the 17th century. The relevance of this is still present in our approach to training in modern martial arts, particularly Wado; weapon or no weapon, we carry a technical legacy that should still be with us, and we should always be trying to identify and reach towards those rarefied goals.

Conclusion.

Ultimately, reading any reliable material in and around your pet subject has to be a good thing. Understanding context, in particular, is crucial to getting under the skin and really understanding what you are doing. Many systems have depth and history and have gone through refinement and transformative processes to get where they are today. Generally speaking, reading is one of the most sure-fire ways of journeying into the cultural lineage of your system.

My view is that reading gives you glimpses of a mindset that is so very different from our own, whether it is the Itosu Letter or master Otsuka’s terse poetic axioms [7] it is clear that the time, the place and the culture inevitably wired-in ways of thinking and looking at the world that have entirely different priorities to the ones we have today. Yes, there are universal principles like justice and a desire for peace, but the societies were structured on pre-industrial almost feudal models (or were in the process of struggling to break free of those models) so it would be a mistake to simply project our views on to their writings.

In part two I intend to take a brief look at more modern examples (that may or may not be written with martial artists in mind) and look at how the west chooses to utilise eastern examples.

Tim Shaw

[1] Early text were hand copied, often generation after generation, remember, printing presses only worked well with European alphabets. Errors occurred, and then were magnified (Chinese Whispers).

[2] I have a particular fascination with the I-Ching, (said to be over 5000 years old). On my bookshelves I have five versions which I tend to compare against each other, the differences are quite startling.

[3] Reference; Ellis Amdur, ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’.

[4] See, https://whitecranegongfu.wordpress.com/2014/12/02/the-bubishi-myth/

[5] Consider the story of how Doshin So the founder of Shorinji Kempo was inspired to create his system after observing a mural painted on the wall of the Shaolin Temple, when he visited in the 1920’s and 30’s, showing Chinese and Indian monks training together. Although Shorinji Kempo history states that it was actually the spirit of training together that inspired Doshin So, not necessarily the technique. But it goes to show how pictorial imagery can inspire ideas.

[6] Itosu Anko is a very important figure in the more recent story of Okinawan karate and features at the point just before karate jumped from the islands to mainland Japan in the form of Itosu’s student Funakoshi Gichin, who was incidentally the first karate teacher of Otsuka Hironori, founder of Wado Ryu. So, in some ways Itosu can be seen as the ‘grandfather’ of the Okinawan karate element contained within Wado.

[7] Master Otsuka composed short poems to express his ideas of how martial arts should function in the world. An example, “On the martial path simple brutality is not a consideration, seek rather an intense pursuit of the way that describes peace”. Source, article by Dave Lowry, ‘A Ryu by any other name’. Black Belt magazine, May 1986.

Bubishi Image credit: ‘Sepai no Kenkyu’ Mabuni Kenwa.

How detailed is your Wado map?

How confident are you about what you know of your system, the discipline you have chosen to study? Are you comfortable with the information you currently have to hand? Do you think you understand the roadmap of that developing knowledge, and is its trajectory obvious and predictable?

Okay, so, I accept that any Wado practitioner reading this might well be at very different points in their journey; some may be just beginning their study, others might be senior practitioners with many years behind them, but the ideas I am going to put forward I am fairly sure would benefit all – or at least stop and make you think. That’s the plan anyway.

Maps.

I am going to start with the broader idea, something I heard a little while ago. There is a theory that we all keep a complete map of the world within our own heads – a personal hardwired version like Google Satellite, Street View and Maps. When I first heard this, I was sceptical.

While I am fully aware that the human brain is perhaps the most complex thing on the planet but really this seemed a bit too far-fetched. But, it is true. That mess of grey matter that sits between our ears that has no awareness of itself outside of its own input devices – our senses, can really do all that, and more!

This amazing mapping, navigation device does not just include places, it also acts as our own personal encyclopaedia, with just about everything there is to be referenced. I use the word ‘referenced’ in a very deliberate way because the reality is that ‘references’ are about all we get.

To explain; while we have this map/encyclopaedia in our head most of this information is patchy and, in many cases, extremely low-resolution. The truth is, we have low-resolution representations of the majority of things we think we know.

Examples:

- Ask yourself about a random country in the world; say, Vietnam? Can you point to it on a map? Probably, but what else can your personalised encyclopaedia tell you? History, culture, language, currency? Unless you know the country very well through direct experience your knowledge will be sketchy, very low-resolution.

- Another couple of words; ‘Steam Train’. To communicate your understanding of this mode of transport, you might draw me a picture of a steam train, complete with funnel and wheels and a cab, all very ‘Thomas the Tank Engine’ – but unless you are an insanely enthusiastic trainspotter with qualifications in engineering and skills in mechanical draughtsmanship, I am not going to be convinced that you really understand a steam train, it will be extremely low-resolution.

Okay, so there are things we might be VERY knowledgeable about (or THINK we are), but the reality of our ‘wired-in’ intelligence and retrieval system (brain) is that it is in a state of constant update, or at least it should be. The truth is that (hopefully) more depth of information is being added and redundant (false) files are being deleted or replaced and new entries or categories are being added.

In some areas, people actually choose not to update their maps and files, this is often found when people become entrenched in areas like politics. Clearly, individuals can be so profoundly tribal in their political beliefs that even in the face of irrefutable evidence they will argue that black is white. But that’s their problem.

How about Wado (or any martial arts system)?

All of the above can be applied to our understanding of Wado karate.

I think it’s a case of being totally honest with yourself; particularly those who have been on this pathway a long time. Come on, do you really believe the same things that you did twenty years ago? How have your files been updated?

An example:

I came to the conclusion a long time back that just about everyone I knew in the martial arts continued their training for completely different reasons than those they started with. It might have been that they initially wanted to build confidence; they were fearful about their ability to protect themselves; but then, over time, their maps changed, their references became more sophisticated, more nuanced and they found something new, something of substance. I can’t get into describing what that is in this post, I don’t have the space; (in some ways I explored this idea in my blog post ‘Martial Arts training and the value of finding your Tribe.’).

Your Wado map.

For every student of Wado karate your initial ‘map’ is usually found in the pages of your syllabus book. This map expands as you move through the grades. Although, I must say, the reality is, it’s not an easily accessible map because it is mostly written in a different language.

But it would be naïve to assume that when we have completed the book we have mastered the system, it doesn’t work like that. The syllabus is a very low-resolution representation of the system; really, it’s a loose framework designed for convenience. In addition, ‘knowing’ the book, with its Kihon, Kata and Kumite doesn’t guarantee you can actually do it; and doing it doesn’t mean you can apply it. Imagine a musician who can read sheet music but can’t play an instrument, or who can play the music accurately but cannot improvise!

The downside of the syllabus book.

In Wado I don’t think reliance on the syllabus book is particularly helpful; it’s a pretty poor map. For me it’s too linear. For systems other than Wado it might easily describe the structure in a straightforward and accurate way, but within Wado karate it only takes you so far in understanding the true nature of this very unique Japanese Budo system. In fact, I would go so far as to say that if the book is the only model/access route, it will ultimately lead you down a dead end. [1]

A different map.

In some of my more recent teaching seminars I have presented a completely different map; a pictorial diagram that I think enables Wado students to navigate a more useful and meaningful way of understanding Wado – but a blog post like this is not the place to share this idea; besides, it is still a work in progress, as it should be. [2]

Expanding the map or increasing the resolution?

I think it is too easy to misread what I mean by developing or expanding the map. I don’t think that the Wado map should be seen as a kind of growing, territorial colonialisation, similar to a video game like ‘The Settlers’ or ‘Minecraft’ where from a tiny localised centre you keep occupying new territory and building new structures; that would be like adding extra pages on the end of the syllabus book.

To give a concrete example: Otsuka Sensei was quite content with the idea of nine core solo kata, anything beyond the apex kata of Chinto was classified as ‘extra’. [3]

Paired kata are perhaps another story. If you take them on face value, they are legion! But to focus on their bewildering number is perhaps missing the point.

I speculate that with the paired kata there is a hidden map lurking beneath the seemingly complicated map which features, for example; the ten Kihon Gumite, the thirty-six Kumite Gata, twenty-four Ura no Kumite and all the rest. The clue is when you acknowledge the reality that none of these paired kata contradict the core principles, and it is these core principles that are the real map, the one skulking underneath, and, in content, the ‘Principle Map’ is not such a huge numerical challenge.

The most valuable approach is not necessarily to expand the territory, but to increase the resolution. The territory might well push beyond its boundaries but only in a natural, unforced way, an organic by-product of more defined and focussed examination. The real payback is in the more granular exploration of areas you already think you know.

‘Low-resolution’ has its uses.

Low-resolution thinking is natural to us, it’s the very basic of what we needed to survive and has been with us for tens of thousands of years. But what might have been paramount for hunter-gatherers has now slipped down our list of priorities – I mean who needs to clutter up their thinking about what they might have had for breakfast when they are being chased by a sabre-tooth cat? A boost of adrenalin and the most basic info about an escape route should be enough!

What does ‘increasing the resolution’ mean for your Wado?

Let me start with what it does NOT mean:

- It does not mean knowing more and more about less and less.

- It does not mean you become a slave to detail, which, if taken to its extreme can result in you looking like an obsessive dilettante, all ‘head knowledge’ and no practical/physical skills. [4]

- It does not limit your thinking by allowing you to assume you have it all pinned down. Actually, the reverse should happen; your mind continues to expand.

What it DOES mean is:

- The more granular your understanding the more you appreciate the relationships between the various parts of your Wado map, the underpinning logic.

- This increased resolution enhances your creativity.

- If approached with humility, you begin to realise how little you know, or how things you thought you knew might have been wrong.

How to adopt a ‘granular’ approach to something you thought you knew.

As an example; never, never, never underestimate or dismiss Kihon, I say that because if you take something like the action of Junzuki, this single technique taught at the beginning of your training reveals so much more depth. Why do you think that no matter how many years you have been training you never leave Junzuki behind, you never transcend it? It’s always a work in progress.

But I guess you expected me to say that.

Another example: Take something like the role of ‘Uke’ in paired kata… it took me far too long to realise that Uke is not a mere stooge for the person performing the prescribed technique. Uke has more say in the conversational process and this ‘conversation’ continues all the way to the end of the kata.

The double-edged sword.

I left this part till the end, but it is incredibly important. Essentially, having knowledge in your head is no good on its own. For it to be given any form of concrete real-world potency, the other form of ‘knowledge’ must accompany it; that is the absorption of the technique into your body, to borrow someone else’s rather excellent description; it must be so deeply engrained that it stains your very bones!

Tim Shaw

[1] Yes, we have a syllabus book in Shikukai, and yes it has its uses as an outline, a catalogue of techniques and requirements for grading, but that’s it.

[2] I have been toying with the idea of sharing this type of material through a subscription service like Substack, but I haven’t made my mind up yet.

[3] Notice how the kata Suparinpei dropped off Otsuka Sensei’s map very early on. Also consider Otsuka’s early development of Wado and look at the list of techniques produced for the official registration in the 1930’s; it’s a kind of map, but what was its objective? Who was the map really for?

[4] ‘Dilettante’, I like this much underused word. Definition; ‘A dilettante was a mere lover of art as opposed to one who did it professionally.’

Photo credit: The Settlers screen image courtesy of: https://www.sockscap64.com/games/game/the-settlers-2/

Personal Security and Society, a Different Perspective.

On the back of the earlier blog posts about self-protection, I thought I would try and look at the bigger picture; particularly as it relates to society.

While I have no qualifications in sociology, criminology or demography I want to present some different ways of looking at things.

The main thrust of this post will be to put forward a series of models that may well clarify a few points and maybe explode a few myths. I will back this up with examples from various sources.

A few basics.

It goes without saying that the reasons for our success as a species is our ability to collaborate, communicate and work as a group to get stuff done with the minimum of friction [1].

To do this you need agreed sets of rules, which over time solidify into laws that we all have to agree to abide by if we want to live within our tribe/society.

And then there are whole swathes of unwritten social nuances which oil the wheels and involve social protocols, good manners, respectful behaviour and not giving in to the destructive, selfish aspects of our basic impulses. We rein ourselves in because we are mindful of the impact of our behaviour on those around us and how that affects our relationships and status in the group. For humans this is incredibly complex, at both the formal/legal level and the more fluid, unwritten domain.

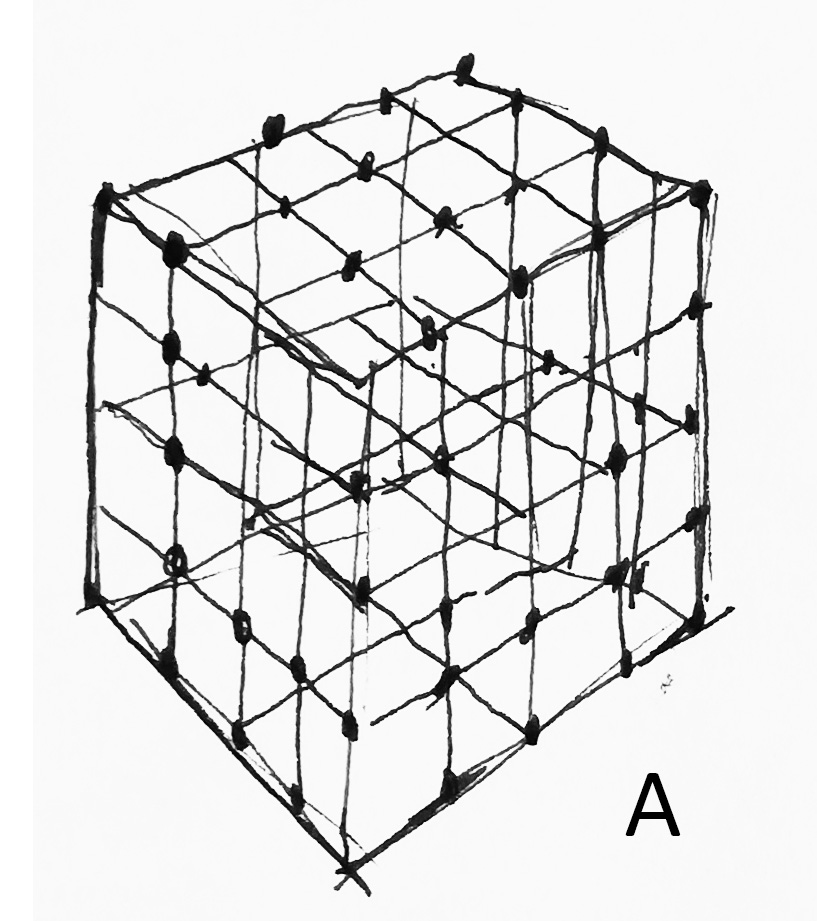

The Framework.

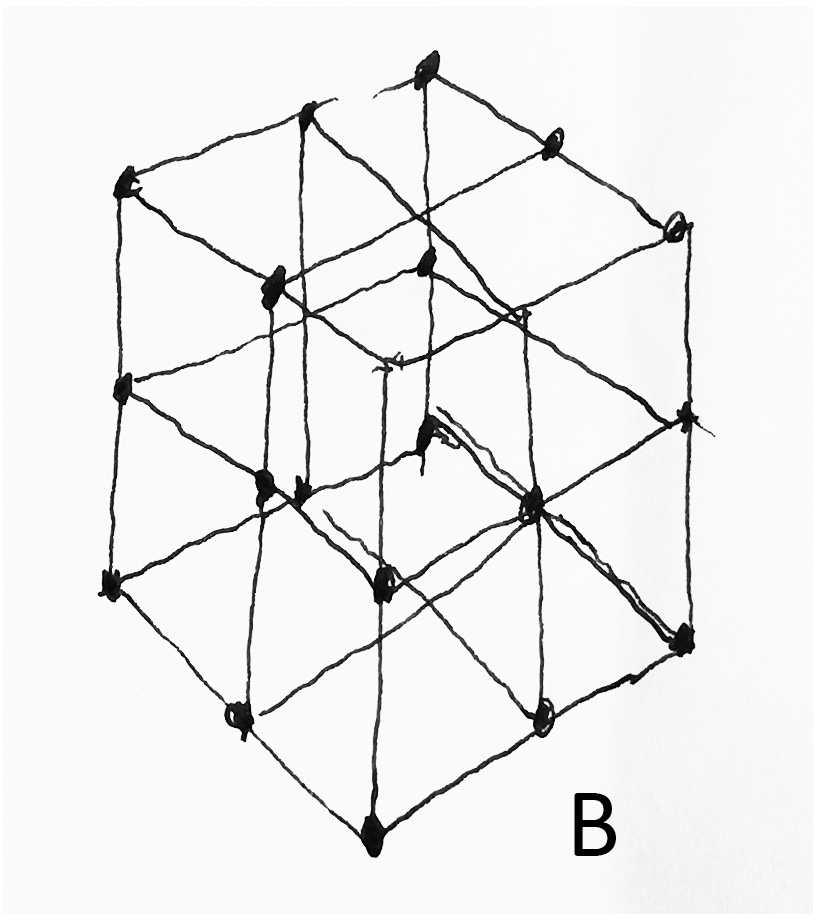

In my mind’s eye I see this as a framework. For me society is like a complex cuboid mesh, of which the strands that hold it together are both our guidelines and our constraints.

Young children grow learning to gradually adopt and navigate this framework. In their very early development it is the parents who construct and manage a world for the child that balances their needs and wants (and freedom of personal expression) and steers them towards what society expects of them.

Gradually these young children become civilised and the process continues to unfold all the way through from their home life to their schooling.

They are expected to create and navigate friendships, as well as stay within the gridlines of first; nursery, then junior school, secondary school and ever onwards. All of these institutions have a secure and complicated framework, which needs to be navigated if they are to survive and thrive. It can be disastrous for a child to fail in this responsibility (for whatever reasons), if they do, they risk being unpopular, ostracised, seen as literally an ‘outsider’ (outside ‘the grid’), which, if left unchecked or unsupported, can breed bitterness and resentment, where any perceived faults are projected outwards onto the big bad world and the people who inhabit it. In its most extreme example, it can lead to events like the Columbine High School shootings of 1999. [2]

Schools as the archetype of ‘the Grid’.

From my experience schools are typical and easily observable examples of this complex gridded cube.

I have seen this first-hand; particularly over the last three years, as a career turn has taken me inside over twenty UK secondary schools, where I have been able to observe them up-close and across all levels.

The ‘framework’ in schools is so very obvious, it even exists as a physical reality – look at the way architects, past and present, design schools. It is manifest in the box-like rooms all stacked on top of each other, connected by corridors and stairwells; even the outdoor spaces tend to be designed to constrict and control; the imagery of the grid is everywhere.

In the last ten years the physical structure of schools has become even more boxed-in; often for what is seen as very good reasons, reasons of ‘safeguarding’ and ‘well-being’, but you have to wonder, has the world become so much more of a dangerous place?

In an ever-escalating arms race of ‘security’, how big is the threat? Does it warrant the explosion of things like; key-coded exterior security gates and fences (are they to keep people out, or to keep people in?); doorways between corridors having to have swipe-card entries; everyone forced to wear lanyards with ID pictures, and (I kid you not) even lock-down zones with metal shutters that grind-down on the press of a panic button, and metal-detector gateways! [3] I have seen all of these.

You have to ask yourself, is this care and kindness geared towards the well-being of children, or is it thinly disguised paranoia that further feeds into the anxiety of young people? What messages are we giving them?

Within the constraints of this tight and complex mesh we are hoping that young people will be able to experience some freedoms and some elements of self-expression, where they can carve out their own unique identity (which, in the UK, is somewhat negated by the contradiction and oddity of the enforced school uniform![4]) I am sure that self-expression happens, but only in the gaps between the gridlines.

Where does the responsibility lie?

It seems to me that headteachers and governors are engaged in a Top Trumps game of who can outdo who in the personal security/safeguarding checklist. I just don’t think they have thought it through.

Safety in the wider world.

What happens to young people when school is no longer part of their lives?

One could suppose that as they have reached adult status the grid is a more open structure, certainly compared to schools.

It might be worth considering the example of the recent red flags that have gone up in UK universities where the apparent slackening of the grid has brought about what seems to be an epidemic of sexual predators – what is the truth behind the reported stories? Why has it been proposed that undergraduates have to have ‘consent training’ etc? [5] Is this a failure of the system, or an inevitable malaise unwittingly constructed by the system itself?

On top of this you have to ask yourself, do these young people have everything they need to survive and thrive, to navigate the bigger open-mesh of society and stay out of harm’s way? Has their education and upbringing given them the necessary tools?

They seem to lurch forward into the adult world with their parent’s words of warning ringing in their ears; but the irony for parents is that a mother’s advice to her teenage daughter as to how to stay safe on a Friday night out with friends is often based on what it was like in the 1990’s, so unless she’s got a time machine, it’s not going to be very helpful. The world changes at a phenomenal rate.

Not all grids are the same.

The societal structures (the grid patterns) are not the same all over the world; yes, they deal with the same basic issues of safety and rules but, for example, the gridlines in Birmingham UK are very different from Tijuana Mexico. (Or even Sarasota Florida).

A cautionary tale about grids.

In 2011 two young British men, James Cooper 25 and James Kouzaris 24, while visiting Mr Cooper’s parents in Sarasota Florida decided to cut out on their own after an evening meal out. They were more than a little drunk, and wandered into a run-down part of Sarasota, a place called Newtown. It appears that Newtown is where the gridlines run out of road.

To cut a long story short, Cooper and Kouzaris were found dead at the side of the road. They had been shot by local boy Shawn Tyson 17, there was no sign of robbery, they both had wallets with money and phones; they just strayed into a blind spot on the grid, one which the locals of Sarasota and Newtown would have surely known about. [6]

This scenario would be unlikely to play out the same way if they were stumbling around Surbiton or Guildford at two in the morning, because they’d recognise the situation, understand their options and be able to navigate the gridlines that were available to them, while calculating the potential of threat or risks inherent to that particular scenario.

Sadly, it is unlikely that any amount of martial arts or hands-on self-defence training would have saved James Cooper and James Kouzaris.

Final word on terrorist threats.

This is a classic case of ‘head says one thing, but heart says another’, but statistically you’d have to be pretty unlucky to get caught up in a terrorist attack in the UK. Yuval Noah Harari the Israeli historian describes terrorism as ‘a puny matter’ when compared to what happens in warfare. It is essentially all spectacle and theatre designed to stoke up fear, and it does, just think about the example of the emotional and human after-effects of the Manchester bombing in 2017.

Essentially, governments and media do the terrorist’s work for them, they supply the oxygen to these combustible situations, and unintentionally become the recruiting sergeants for the next generation of terrorists through ill-thought out knee-jerk reactions. But, as they know, you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t.

Read Yuval Noah Harari’s piece in the Guardian, for a good description of how this works at a rational level.

Keep safe.

Tim Shaw

[1] As individuals in the animal kingdom we make pretty lousy predators; we are not particularly strong, agile or bulky to survive on our own without the employment of weaponry, and even then we have to operate in packs to achieve any level of success.

[2] Columbine High School Shootings https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbine_High_School_massacre

[3] Most schools I have visited have ‘lock-down procedures’, some have interior door wedges with the fear of the possibility of an ‘active shooter’, and this is the UK not the USA. The UK has only ever experienced three school shootings and all of the casualties (bar 1) occurred in just one incident. Compare that to the USA, where between the year 1999 and 2012 there have been 31 school shootings.

[4] Radical educationalist professor Guy Claxton said that schools tend to be constructed on one of two models; the are either ‘monasteries’ or ‘factories’. ‘Monasteries’ have; authorities in gowns/robes with other robes/uniforms for novices and are based upon some vague notion of revelation, with a massive worship of ‘tradition’. While ‘factories’ have bells to end shifts and have the intention of turning out identical little ‘products’ and are judged by quality controllers (Ofsted, Performance management etc), they won’t admit it but they are really exam factories. I know this because for a long time I worked in a factory that was built on the ruins of a monastery.

[5] Consent training and even ‘Good Lad workshops’ in universities and colleges. See this link from the University of Cambridge https://www.breakingthesilence.cam.ac.uk/training-and-events/training-students

[6] Murder in Florida, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-17479559

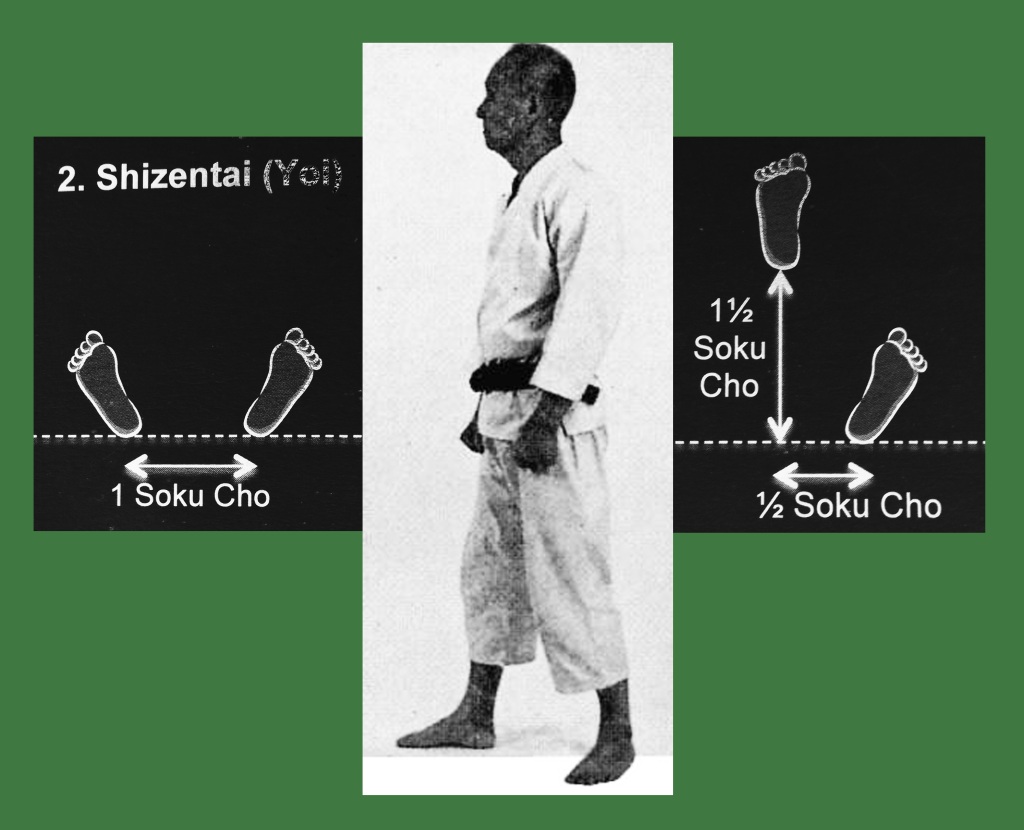

Shizentai.

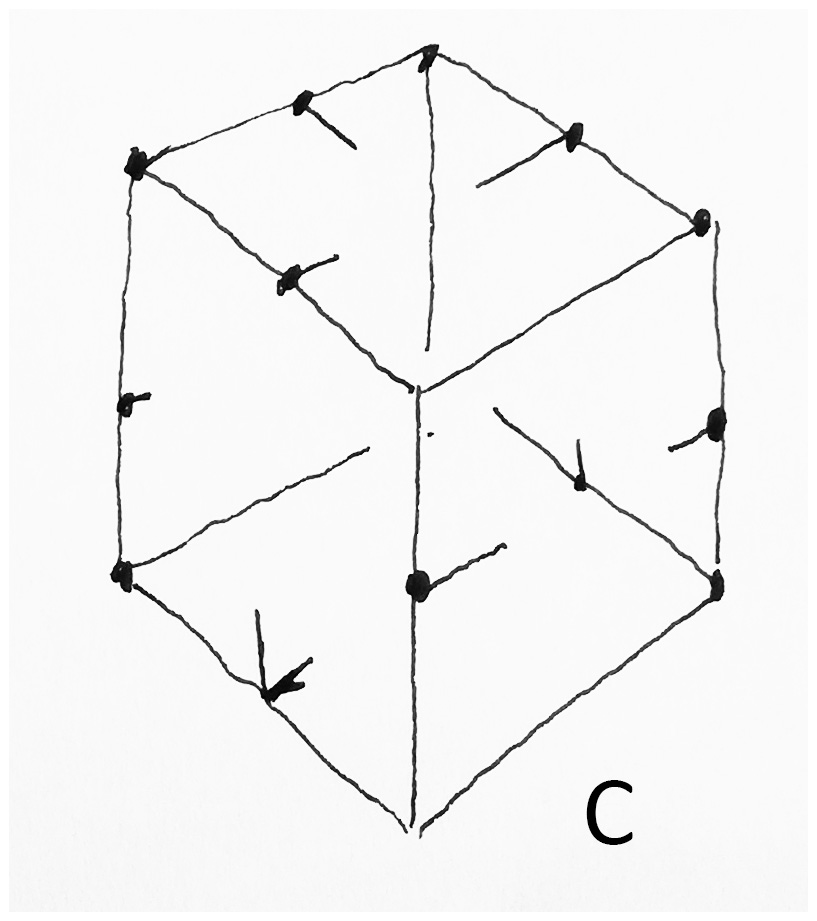

Look through most Wado syllabus books and a few text books and you are bound to see a list of stances used in Wado karate; usually with a helpful diagram showing the foot positions.

One of the most basic positions is Shizentai; a seemingly benign ‘ready’ position with the feet apart and hands hanging naturally, but in fists. It is referred to as ‘natural stance’, mostly out of convenience; but as most of us are aware, the ‘tai’ part, usually indicated ‘body’, so ‘natural body’ would be a more accurate fit. [1].

In this particular post I want to explore Shizentai beyond the idea of it being a mere foot position, or something that signifies ‘ready’ (‘yoi’). There are more dimensions to this than meets the eye.

Let me split this into two factors:

- Firstly, the very practical, physical/martial manifestation and operational aspects.

- Secondly, the philosophical dimension. Shizentai as an aspiration, or a state of Mind.

Practicalities.

The physical manifestation of Shizentai as a stance, posture or attitude seems to suggest a kind of neutrality; this is misleading, because neutrality implies inertia, or being fixed in a kind of no-man’s land. The posture may seem to indicate that the person is switched off, or, at worst, an embodiment of indecisiveness.

No, instead, I would suggest that this ‘neutrality’ is the void out of which all possibilities spring. It is the conduit for all potential action.

Isn’t it interesting that in Wado any obvious tensing to set up Shizentai/Yoi is frowned upon; whereas other styles seem to insist upon a form of clenching and deliberate and very visual energising, particularly of the arms? As Wado observers, if we ever see that happening our inevitable knee-jerk is to say, ‘this is not Wado’, or at least that is my instinct, others may disagree.

Similarly, in the Wado Shizentai; the face gives nothing away, the breathing is calm and natural, nothing is forced.

In addition, I would say that in striking a pose, an attitude, a posture, you are transmitting information to your opponent. But there is a flip-side to this – the attitude or posture you take can also deny the opponent valuable information. You can unsettle your opponent and mentally destabilise him (kuzushi at the mental level, before any physical contact has happened). [2]

Shizentai as a Natural State – the philosophical dimension.

I mentioned above that Shizentai, the natural body goes beyond the corporeal and becomes a high-level aspiration; something we practice and aim to achieve, even though our accumulated habits are always there to trip us up.

In the West we seem to be very hung up on the duality of Mind and Body; but Japanese thinking is much more flexible and often sees the Mind/Body as a single entity, which helps to support the idea that Shizentai is a full-on holistic state, not something segmented and shoved into categories for convenience.

This helps us to understand Shizentai as a ‘Natural State’ rather than just a ‘Natural Body(stance)’.

But what is this naturalness that we should be reaching for?

Sometimes, to pin a term down, it is useful to examine what it is not, what its opposite is. The opposite of this natural state at a human level is something that is ‘artificial’, ‘forced’, ‘affected’, or ‘disingenuous’. To be in a pure Natural State means to be true to your nature; this doesn’t mean just ‘being you’, because, in some ways we are made up of all our accumulated experiences and the consequences of our past actions, both good and bad. Instead, this is another aspect of self-perfection, a stripping away of the unnecessary add-ons and returning to your true, original nature; the type of aspiration that would chime with the objectives of the Taoists, Buddhists and Neo-Confucians.

Although at this point and to give a balanced picture I think it only fair to say that Natural Action also includes the option for inaction. Sometimes the most appropriate and natural thing is to do nothing. [3]

Naturalness as it appears in other systems.

In the early days of the formation of Judo the Japanese pioneers were really keen to hold on to their philosophical principles, which clearly originated in their antecedent systems, the Koryu. Shizentai was a key part of their practical and ethical base. [4] In Judo, at a practical level, Shizentai was the axial position from which all postures, opportunities and techniques emanated. Naturalness was a prerequisite of a kind of formless flow, a poetic and pure spontaneity that was essential for Judo at its highest level.

Within Wado?

When gathering my thought for this post I was reminded of the words of a particular Japanese Wado Sensei. It must have been about 1977 when he told us that at a grading or competition he could tell the quality and skill level of the student by the way they walked on to the performance area, before they even made a move. Now, I don’t think he was talking about the exaggerated formalised striding out you see with modern kata competitors, which again, is the complete opposite of ‘natural’ and is obviously something borrowed from gymnastics. I think what he was referring to was the micro-clues that are the product of a natural and unforced confidence and composure. For him the student’s ability just shone through, even before a punch was thrown or an active stance was taken.

This had me reflecting on the performances of the first and second grandmasters of Wado, particularly in paired kata. On film, what is noticeable is their apparent casualness when facing an opponent. Although both were filmed in their senior years, they each displayed a natural and calm composure with no need for drama. This is particularly noticeable in Tanto Dori (knife defence), where, by necessity, and, as if to emphasise the point, the hands are dropped, which for me belies the very essence of Shizentai. There is no need to turn the volume up to eleven, no stamping of the feet or huffing and puffing; certainly, it is not a crowd pleaser… it just is, as it is.

As a final thought, I would say to those who think that Shizentai has no guard. At the highest level, there is no guard, because everything is ‘guard’.

Tim Shaw

[1] The stance is sometimes called, ‘hachijidachi’, or ‘figure eight stance’, because the shape of the feet position suggests the Japanese character for the number eight, 八.

[2] Japanese swordsmanship has this woven into the practice. At its simplest form the posture can set up a kill zone, which may of may not entice the opponent into it – the problem is his, if he is forced to engage. Or even the posture can hide vital pieces of information, like the length or nature of the weapon he is about to face, making it incredibly difficult to take the correct distance; which may have potentially fatal consequences.

[3] The Chinese philosopher Mencius (372 BCE – 289 BCE) told this story, “Among the people of the state of Song there was one who, concerned lest his grain not grow, pulled on it. Wearily, he returned home, and said to his family, ‘Today I am worn out. I helped the grain to grow.’ His son rushed out and looked at it. The grain was withered”. In the farmer’s enthusiasm to enhance the growth of his crops he went beyond the bounds of Nature. Clearly his best course of action was to do nothing.

[4] See the writings of Koizumi Gunji, particularly, ‘My study of Judo: The principles and the technical fundamentals’ (1960).

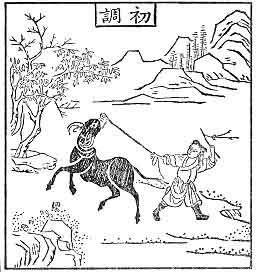

The Ten Ox Herding Pictures.

If you have an interest in Zen and the martial arts, you may or may not have come across the allegory of ‘The Ten Ox Herding Pictures’.

I have been meaning to post on this subject for a while now, and although I am not really a committed Zen Buddhist adherent by any significant measure, I have an outsider’s interest.

Before I get into it in any detail, let me say that I don’t see this allegory as uniquely ‘Zen’, I think it has a wider application, particularly for anyone exploring the conundrum of self-realisation and self-actualisation.

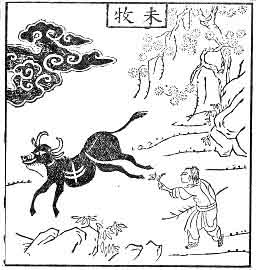

The ten images tell a story of a boy, the ox-herd, and his search for the missing ox and is a metaphor of the search for the true self (the original self); in Buddhist terms, the search for Awakening and the True Reality. The Ox-herd is the smaller self, the ego, who gradually realises that the reality is actually not far away and ultimately contained within him.

History.

Although these images developed a considerable following inside Japan, they are definitely Chinese in origin (as is Zen Buddhism actually). The earliest record of this sequence of images as a metaphor date back to the 11th or 12th century in China. There are usually accompanied by poems, but I would argue that you really don’t need them. At a visual level, you fill in the blanks with your imagination – no need for words – so very ‘Zen’.

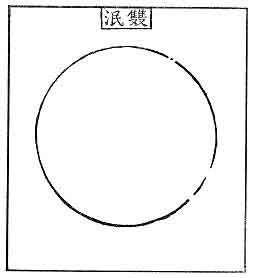

The key differences between the various versions are usually found in the last three pictures. Some versions are content to just complete the series with a blank circle, (which particularly resonates with me), but, arguably, others have a deeper story to tell, making the final picture one of a Buddha or Boddhisatva in the ‘market place’, as if to say, ‘once enlightenment is complete, return to the world, to the busiest place and just ‘be’, amongst the people’. I like that – nobody disappears up into a mountain cave; that is not the place for the sage or the enlightened one. This is a philosophy that is nearer to the Neo-Confucianists, who I believe, have a closer resonance with the martial arts that we know. [1]

A description.

A boy is out in the countryside clearly looking for something. He is sometimes shown holding a kind of tether in his fist. (The wildness of the landscape increases as the narrative develops, as if to underline the difficulty of the quest).

At first he sees the ‘traces’ of the ox (which is sometimes referred to as a bull). Whether this is tracks, or even other things bulls and oxen tend to leave behind, is not really clear.

He catches a glimpse of the untamed ox. This wild spirit shows him a ‘Way’, it’s a hint, but it gives him direction and purpose. This is the beginning of ‘Do’ or ‘Tao’.

The boy pursues the ox, taking to his task with great determination. He finally connects with the animal and manages to attach the tether to it. The hard work begins. It’s a battle between the raw energy of the ox and the willpower and determination of the boy.

The boy is unaware that he is wrestling with his own true nature and trying to bridge the gulf between his uncultured petty ego and the untainted purity of his elemental self. The Buddhists enjoy the use of metaphor to describe this pure self; they are particularly fond of the image of a lotus flower that rises in its purity from the mud of the pond, perfect and unfouled. This is the true self that resides in all of us that remains pure and clean however much with sully it our own self-inflicted contaminants; which, with discipline, can shine forth again.

This is the discipline of the Dojo and the trials of the martial way; whether you want to describe it as a form of self-transformation (internal alchemy), or the ‘forging’ process of Tanren, it is a deep emersion in the greater process of training.

The disciplining of the ox in the various versions usually seems to take a couple of pictures, as if to accentuate the battles that occur between the boy and the ox. Gradually the creature succumbs to harness and becomes placid and resigned to the process. (In some versions the ox starts out pure black in colour and by degrees changes to white).

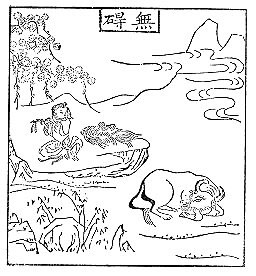

Eventually the boy and the ox establish a harmonious union. The boy is shown riding sedately on the ox’s back, playing his flute, without a care or worry in the world. This is sometimes referred to as ‘coming home’.

In the next pictures the boy and the ox are unconcerned about each other’s presence, there is no battle any more, there is no division; they exist in the same space because there is nothing to separate them; they are one and the same; this is a state of total harmony.

The next image is often described as ‘all forgotten’. The transition is virtually complete; nothing matters. The boys is there, the ox is there, but it is as if nothing is of consequence to either of them; it is just ‘being’.

The final images plunge deeply into the unknown and the esoteric, I don’t pretend to understand them, this is ‘returning to the origin’, whether you want to call this ‘the Great Tao’ or the ‘Universal Divine’ is up to you.

As an aside; many years ago, in my college education, myself and my fellow students were introduced to a retired educationalist, I wish I could remember his name. He was a very strange individual, very calm and patient, he spoke to us as if we were his children, but not in a condescending way. Here was a man who had lived a very full life (I think he’d been in the military during WW2). He encouraged us to ask searching questions, far beyond the limited educational brief. As the discussion opened out we found ourselves questioning the meaning of existence. He talked about ‘answers’ and I asked him, ‘what happens after you find all of the ‘answers?’ He paused slightly and then said, ‘You just… disappear’.

I remember, he smiled and just left that hanging in the air. If I am reading his reply correctly, this was the final message of the ox herding pictures. Here was the blank circle, or the empty landscape.

Leonard Cohen.

This set of pictures had a further reach than most of us realised.

I don’t know how many people are aware of this but singer songwriter Leonard Cohen had a soft spot for the ox herding narrative. I think it is common knowledge that Cohen plunged deeply into the Zen lifestyle, secluding himself in monastic Zen disciplines, indulging in harsh regimes of Zazen (seated meditation).

Some of his most thoughtful and erudite poetry and lyric writing came out of that experience. What ever you think of his vocal style and singing ability there is no getting away from the fact that Cohen was a talent that maybe even eclipsed Dylan. But people seemed not to have noticed a track called ‘The Ballad of the Absent Mare’ which featured on his 1979 album, ‘Recent Songs’.

Canadian singer songwriter Jennifer Warnes recounts how Cohen came over to her house after a meditational retreat, she said, “Leonard had found some old pictures somewhere, they were called ‘The Ten Bulls’, old Japanese woodcuts symbolizing the stages of a monk’s life on the road to enlightenment. These carvings pictured a boy and a bull, the boy losing the bull, the bull hiding, the boy realizing that the bull was nearby all along. There is a struggle, and finally the boy rides the bull into his little village. ‘I thought this would make a great cowboy song,’ he joked.” [2]

Here is a sample of Cohen’s ‘cowboy song’, obviously replace ‘mare’ with ‘ox’ and it’s the same tale:

“Say a prayer for the cowboy, his mare’s run away

And he’ll walk ’til he finds her, his darling, his stray

But the river’s in flood and the roads are awash

And the bridges break up in the panic of loss

And there’s nothing to follow, there’s nowhere to go

She’s gone like the summer, gone like the snow

And the crickets are breaking his heart with their song

As the day caves in and the night is all wrong

Did he dream, was it she who went galloping past?

And bent down the fern, broke open the grass

And printed the mud with the iron and the gold

That he nailed to her feet when he was the lord

And although she goes grazing a minute away

He tracks her all night, he tracks her all day

Oh, blind to her presence, except to compare

His injury here with her punishment there…”

Conclusion.

For this story/allegory to have been around for such a long time says something about its cultural power and its spiritual value. If you take any of the great or iconic stories that have stayed with humanity all the way from antiquity to the present day, their survival is an indication of what they have to teach us, as well as their resonance with the human condition; from the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ (2100 BCE) to ‘Moby Dick’, they present models and narratives that touch and inspire us.

The ox herd pictures could be seen as a compressed version of what Joseph Campbell refers to as the ‘Hero’s journey’ [3], but Campbell’s journey has 17 stages rather than 10. Campbell’s idea is so deeply engrained into western culture that we take it for granted; examples are: Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, ‘Star Wars’, ‘The Matrix’ and even ‘Harry Potter’.

The ox herd pictures are more overtly spiritual, but given their transcendent narrative there is much there to tie in to the martial artist’s personal odyssey, after all, martial arts also aspire to a transcendence, a development of character, a personal alchemy. Let us not pretend that our martial arts journey is devoid of spirituality; by that I don’t mean the ‘Spirituality’ that is allied to organised religion; but instead, the more secular brand, associated with pondering things that are outside and beyond yourself and your whole purpose of being alive and conscious and the meaning of your existence. Buddhism sought to address these puzzles without the need to resort to Gods or supernatural deities (although certain forms of Buddhism never quite shook off the shackles of shamanism, adding things that were never part of the original message).

Of course, martial arts people tend to be very pragmatic and deep meditation on spiritual matters are not to everyone’s taste. My thinking is that while I have no desire to become a Zen Buddhist there is something to gain from exploring the wider cultural context.

But that’s my view – to you, it might just be a load of old Bull.

For those of you have an inclination towards trivia; Cat Stevens’ 1972 studio album ‘Catch Bull at Four’ is an obvious reference, which may well have flown right over the head of the average pop music fan of the 1970’s. The album cover makes it very clear.

Tim Shaw

[1] Through personal research and correspondence with experts in the field, I have come to the opinion that works related to the Japanese martial arts that have been pegged as coming from the Zen tradition are actually Neo-Confucian in origin, e.g. Takuan Soho ‘The Unfettered Mind’.

[2] Source: https://www.songfacts.com/facts/leonard-cohen/ballad-of-the-absent-mare

[3] See Joseph Campbell’s ‘Hero with a Thousand Faces’. 1949.

If you are interested in the crossovers between far eastern traditions and philosophy and western psychology, I found that this book has some interesting sections relating to the Ox Herding Pictures; ‘Buddhism and Jungian Psychology’, J. Marvin Spiegelman and Mokusen Miyuki, 1994.

Other references and links:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Bulls

For an excellent description of the series follow this link: https://jessicadavidson.co.uk/2015/10/02/zen-ox-herding-pictures-introduction/

For the full lyrics by Leonard Cohen’s ‘The Ballad of the Absent Mare’ follow this link: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/leonardcohen/balladoftheabsentmare.html

The image featured for ‘Catch Bull at Four’ is sourced from Wikipedia with the appropriate copyright stipulations cited here: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/3/3d/Catch_Bull_at_Four.jpg

Ox herding pictures courtesy of: https://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/mzb/oxherd.htm

Wado on Film (Anything on film!) – Part 1.

On the surface it would appear that we are blessed to have so much film of the founder of Wado Ryu available to us. It is lucky that Otsuka Hironori was not camera shy and showed enough foresight to actually have himself recorded with the intention of securing the legacy of his techniques and ideas for future generations. I have heard that there is even more unseen material that has been archived away, held secure by his inheritors.

Although it is interesting that there seem to be zero examples of film of Otsuka Sensei as a younger man; while there are photographs a plenty. (Otsuka Sensei was born in 1892 and only passed away in 1982).

He appeared to hit his filmic stride in his mid-seventies. Although a while back, a tiny snippet of footage of the younger Otsuka did appear as almost an afterthought on a JKA Shotokan film. It was a bare couple of seconds, it certainly looked like him – he was demonstrating at some huge martial arts event in Japan; the year is uncertain, but I am guessing some time in the 1950’s. In this film there was an agility and celerity to his movements which is not so evident in his later years. [1]

Historically, it does seem odd that there is so little film available from those years of such a celebrated martial artist.

Ueshiba Morihei, the founder of Aikido has a film legacy that goes back to a significant and detailed movie shot in 1935 at the behest of the Asahi News company. Ueshiba was then a powerful 51-year-old, springing around like a human dynamo, it’s worth watching. [LINK]

On first viewing that particular film it left me scratching my head; initial examination told me that the techniques looked so fake. But the more I watched, there were individual moments where some strange things seemed to happen (at one point his Uke is propelled backwards like an electric shock had gone through him). At times Uke seems to attempt to second-guess him and finds himself spiralling almost out of control. Really interesting.

But for Wado, is this even important? Why does it matter? Afterall, Wado Ryu had already been launched across the world, much of which happened during Otsuka Sensei’s lifetime. Also, the first and second generation instructors were doing the best of a difficult job to channel Otsuka Sensei’s ideas.

So, what can we gain from watching flickering images of master Otsuka showing us the formalised kata or kihon? What value does it have?

I saw Otsuka Sensei in person in 1975. I watched in awe his demonstration on the floor of the National Sports Centre, Crystal Palace in London. I was only seventeen years old. I remember thinking at the time, ‘here is something very special going on in front of my eyes – I know that – but I can’t put my finger on exactly what it is’.

At that age and the particular stage of my development, I had very little to bring to the experience. I lacked the tools. Possibly the only advantage I had at that time was I was carrying no baggage, no preconceptions; maybe that is why the memory has stayed so clear in my mind [2].

Interestingly, Aikido founder master Ueshiba’s own students, in later interviews lamented that they wished they’d paid more attention to exactly what he was doing when he was demonstrating in front of them; even when he laid hands upon them, they still struggled to get it.

Can we ever hope to bridge the gap?

I think it is useful to acknowledge the problem. The reality is that we are THERE but NOT THERE; we are SEEING but not SEEING. I believe that we often lack the refined tools to understand what is really going on and what is really useful to us as developing martial artists. It comes down in part to that old ‘subjectivity’ versus ‘objectivity’ problem; can we ever be truly objective?

But it is the evanescence of the experience; it flickers and then it is gone and all we are left with is a vain attempt to grasp vapour. But isn’t that the essence of everything we do as martial artists?

To explain:

Two forms of artefact.

I read recently that in Japanese cultural circles they acknowledge that there are two forms of artefact; ones with permanence, solidity and material substance, and ones with no material substance, but both of equal value.

The first would include paintings, prints, ceramics and the creations of the iconic swordsmiths. For example, you can actually touch, hold, weigh, admire a 200 year old Mino ware ceramic bowl, or a blade made by Masamune in the early 14th century – if you are lucky enough. These are real objects made to last and to be a reflection of the artist’s search for perfection; they live on beyond the lifetime of their creator.

But the second, only loosely qualifies as an artefact as it has no material substance, or if it does it has a substance that is fleeting. This is part of the Japanese ‘Way of Art’ Geido.

There are many examples of this but the best ones are probably the Tea Ceremony (Sado) and Japanese Flower Arranging (Kado). Even the art of Japanese traditional theatre which is so culturally iconic actually leaves no lasting material artefact.

In the Tea Ceremony the art is in the process and the experience. Beloved of its practitioners is the phrase, ‘Ichi go, Ichi e’ which means ‘[this] one time, one place’.

The martial arts also leave no material permanence behind. Their longevity and survival are based upon their continued tradition (this is the meaning of ‘Ryu’ as a ‘stream’ or ‘tradition’, it seems to work better than ‘school’). The tradition manifests itself through the practitioners and their level of mastery; this is why transmission is so important. But a word of caution; the best traditions survive not in a state of atrophy, but as an evolving improving entity. It is all so very Darwinian. Species that fail to adapt to a changing environment and just keep chugging on and doing what they always do soon become extinct species.

Film (Nijinky, a case history).

Vaslav Nijinsky (1890 – 1950) was the greatest male ballet dancer of the 20th century. He was probably at his majestic peak around about 1912 as part of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. To his contemporaries Nijinsky was a God; he could do things other male dancers could only dream of; he danced on pointe and his leaps almost seemed to defy gravity. As this quote from the time tells us:

“An electric shock passed through the entire audience. Intoxicated, entranced, gasping for breath, we followed this superhuman being… the power, the featherweight lightness, the steel-like strength, the suppleness of his movements…”.

But, there was never any film made of this amazing dancer, so, all we have left are these words. Even though, at the time, movie-making was on the rise (D. W. Griffith was knocking out multiple movies in the USA in 1912 and earlier). At the time the dance establishment distrusted the new medium of moving pictures, they feared that it trivialised their art and turned it into a mere novelty; which clearly proved to be incredibly short-sighted.

If Nijinsky, arch-performer, had anything to teach the world of dance it is lost to us. Incidentally it is said that Nijinsky destroyed his mind through the discipline of his body. He ended his days in and out of asylums and mental hospitals.

We will never know how good Nijinsky was in comparison to modern dancers, or if it was all a big fuss about nothing. But then again, the very same could be said about any famous performer, sportsperson or martial artist born before the invention of moving pictures.

Other forms of recollections or records that act as witnesses.

A writer or composer leaves behind another form of record. For composers before the first sound recordings in 1860 it was in the form of published written music or score. We would assume that this would be enough to contain the genius of past musicians?

But maybe not.

Starting right at the very apex of musical genius, what about Mozart?

Well, maybe those written symphonies, operas etc. were not a faithful reflection of the great man? Certainly, there is some dispute about this. There has been a suggestion that rather like the plays of Shakespeare, all we have left are stage directions, (with Shakespeare the actors slotted in whatever words they thought were appropriate!).

We judge Mozart not only by todays orchestral/musical performances, but also by his completed score on the page, and some may see these pages as a distillation of Mozart’s genius; but perhaps Mozart’s real genius was expressed through something we would never see written down, thus, today, never performed? This was his ability to improvise and elaborate around a stripped-back musical framework. It is reported that he was able to weave his magic spontaneously. As an example, Mozart was known to only write the violin parts for a new premier performance, allowing the piano parts, which he was to play, to come straight out of his head. We have no idea how he did it, or what it might have sounded like.

More on this developing theme in the second part. What point is there to all this chasing of shadows? Are we kidding ourselves? Can we be truly objective to what we are seeing?

Part 2 coming shortly.

Tim Shaw

[1] If anyone is able to track down this piece of film, I would be grateful if they would let me know the URL. It seems to have disappeared from YouTube, or my search skills are not what they used to be.

[2] This was the same year as the IRA bomb scare, as well as Otsuka Sensei getting the back of his hand cut by his attacker’s sword.

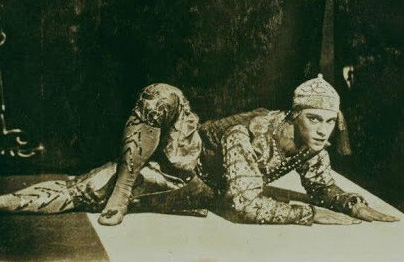

Image of Nijinsky (detail). Nijinsky in ‘Les Orientales’ 1911. Image credit: https://www.russianartandculture.com/god-only-knows-tate-modern/

Is Stoicism useful to martial artists?

Apparently, sales of books about Stoicism have rocketed during the pandemic. Why would there be a surge in interest about a school of ancient philosophy which is over 2000 years old?

Maybe, because one of the specific skill-sets associated with the Stoics is dealing with adversity; which is exactly why the Stoics may well have something to offer martial artists.

It is strange how the word ‘Stoic’ is used today. When you hear of anyone described as behaving stoically, it usually suggests that they are putting up with bad experiences or bad times in an uncomplaining way, or displaying zero emotion, or perhaps indifference to pain, grief (or even happiness). This is a little misleading and over-simplistic, and on its own, not particularly useful.

For anyone who has not heard of Stoicism before, a potted history may be necessary.

Stoicism is a school of philosophy originating in ancient Greece and enthusiastically embraced by key individuals in the later Roman Empire. It was established in the 3rd century BCE by Zeno of Citium in the city of Athens. Its main themes were the search for wisdom, virtue and human perfection.

After the Greeks it was eagerly embraced in ancient Rome, first by Seneca (4BCE – 65CE) a writer, politician and philosopher who was heavily embroiled in the politics associated with emperors Claudius and Nero and miraculously escaping two death sentences. Seneca’s ‘Letters from a Stoic’ is one of my go-to reads, an amazingly modern sounding set of conversations coming out of the long-distant past.

Stoicism was then picked up by Epictetus (50CE – 135CE) an educated Greek slave who lived in Rome, but was later exiled to Greece. He left no direct writings, but had one faithful disciple, Arrian, who dutifully wrote everything down.

Perhaps one of the most famous and accessible of the Stoics was the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (121CE – 180CE). Anyone who has seen the movie ‘Gladiator’ may remember that Marcus Aurelius appeared in the very early part of the movie played by Richard Harris, and although he actually did die of unknown causes whilst on a military campaign at the age of 58, it was unlikely it was at the hands of his son and successor Commodus, as the movie suggests, but why let the truth get in the way of a good story?

Marcus Aurelius was the last of the great and virtuous Roman emperors. Fortunately for us, he left behind a book, now titled, ‘Meditations’ and it is this book of Stoic wisdom that has been snapped up in the recent Covid year.

I had wondered if any modern martial artists had picked up on the Stoics? While there are a few online references, the tone very much suggested to me a misappropriation and over-simplified cherry picking; reminding me of how a particular disreputable 20th century fascist regime (who will not be mentioned) misappropriated and misunderstood the writings of Fredrich Nietzsche.

Yes, some of the writings of the Stoics seem to suggest a kind of toughness, but Stoicism is a bigger package, involving elements of compassion and love. This perceived ‘toughness’ emanates from the Stoics’ detailed dissection of human motivation and how we should respond to the trials of just living. What is really of value, matched against what is trivial and not worthy of our attention.

It is a very pragmatic, workable philosophy. I often wonder if boxer Mike Tyson may perhaps have been influenced by the Stoics when he said, “Everyone has a plan, ‘till they get punched in the mouth.” That might have come straight out of Marcus Aurelius’’ ‘Meditations’. He would have liked that.