self-defence

Personal Security and Society, a Different Perspective.

On the back of the earlier blog posts about self-protection, I thought I would try and look at the bigger picture; particularly as it relates to society.

While I have no qualifications in sociology, criminology or demography I want to present some different ways of looking at things.

The main thrust of this post will be to put forward a series of models that may well clarify a few points and maybe explode a few myths. I will back this up with examples from various sources.

A few basics.

It goes without saying that the reasons for our success as a species is our ability to collaborate, communicate and work as a group to get stuff done with the minimum of friction [1].

To do this you need agreed sets of rules, which over time solidify into laws that we all have to agree to abide by if we want to live within our tribe/society.

And then there are whole swathes of unwritten social nuances which oil the wheels and involve social protocols, good manners, respectful behaviour and not giving in to the destructive, selfish aspects of our basic impulses. We rein ourselves in because we are mindful of the impact of our behaviour on those around us and how that affects our relationships and status in the group. For humans this is incredibly complex, at both the formal/legal level and the more fluid, unwritten domain.

The Framework.

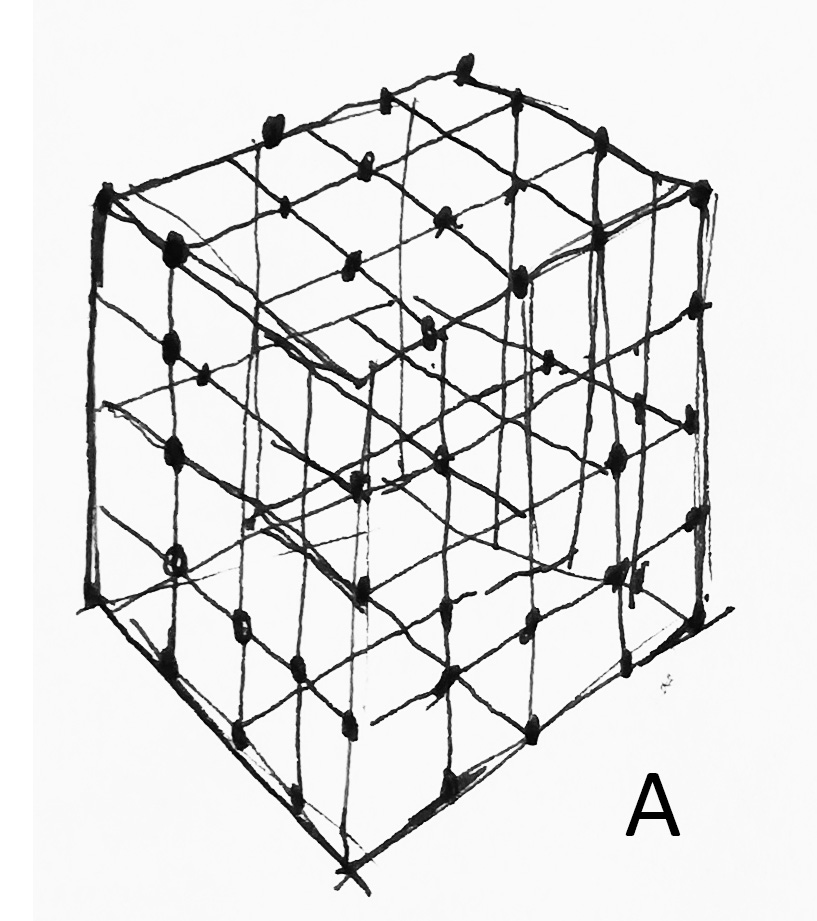

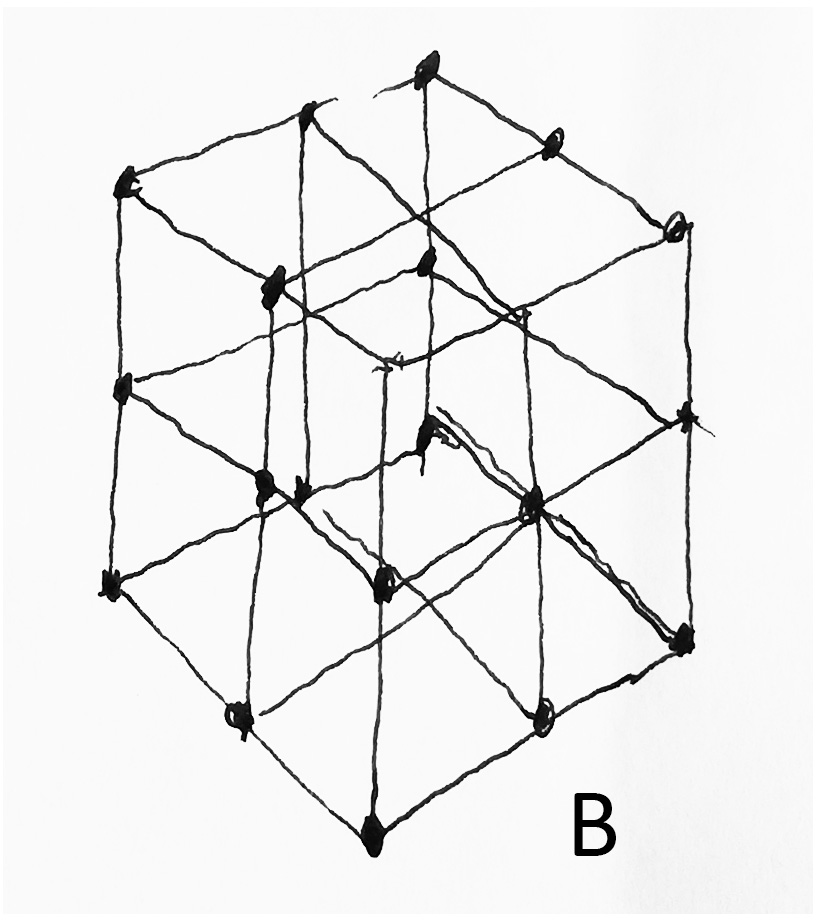

In my mind’s eye I see this as a framework. For me society is like a complex cuboid mesh, of which the strands that hold it together are both our guidelines and our constraints.

Young children grow learning to gradually adopt and navigate this framework. In their very early development it is the parents who construct and manage a world for the child that balances their needs and wants (and freedom of personal expression) and steers them towards what society expects of them.

Gradually these young children become civilised and the process continues to unfold all the way through from their home life to their schooling.

They are expected to create and navigate friendships, as well as stay within the gridlines of first; nursery, then junior school, secondary school and ever onwards. All of these institutions have a secure and complicated framework, which needs to be navigated if they are to survive and thrive. It can be disastrous for a child to fail in this responsibility (for whatever reasons), if they do, they risk being unpopular, ostracised, seen as literally an ‘outsider’ (outside ‘the grid’), which, if left unchecked or unsupported, can breed bitterness and resentment, where any perceived faults are projected outwards onto the big bad world and the people who inhabit it. In its most extreme example, it can lead to events like the Columbine High School shootings of 1999. [2]

Schools as the archetype of ‘the Grid’.

From my experience schools are typical and easily observable examples of this complex gridded cube.

I have seen this first-hand; particularly over the last three years, as a career turn has taken me inside over twenty UK secondary schools, where I have been able to observe them up-close and across all levels.

The ‘framework’ in schools is so very obvious, it even exists as a physical reality – look at the way architects, past and present, design schools. It is manifest in the box-like rooms all stacked on top of each other, connected by corridors and stairwells; even the outdoor spaces tend to be designed to constrict and control; the imagery of the grid is everywhere.

In the last ten years the physical structure of schools has become even more boxed-in; often for what is seen as very good reasons, reasons of ‘safeguarding’ and ‘well-being’, but you have to wonder, has the world become so much more of a dangerous place?

In an ever-escalating arms race of ‘security’, how big is the threat? Does it warrant the explosion of things like; key-coded exterior security gates and fences (are they to keep people out, or to keep people in?); doorways between corridors having to have swipe-card entries; everyone forced to wear lanyards with ID pictures, and (I kid you not) even lock-down zones with metal shutters that grind-down on the press of a panic button, and metal-detector gateways! [3] I have seen all of these.

You have to ask yourself, is this care and kindness geared towards the well-being of children, or is it thinly disguised paranoia that further feeds into the anxiety of young people? What messages are we giving them?

Within the constraints of this tight and complex mesh we are hoping that young people will be able to experience some freedoms and some elements of self-expression, where they can carve out their own unique identity (which, in the UK, is somewhat negated by the contradiction and oddity of the enforced school uniform![4]) I am sure that self-expression happens, but only in the gaps between the gridlines.

Where does the responsibility lie?

It seems to me that headteachers and governors are engaged in a Top Trumps game of who can outdo who in the personal security/safeguarding checklist. I just don’t think they have thought it through.

Safety in the wider world.

What happens to young people when school is no longer part of their lives?

One could suppose that as they have reached adult status the grid is a more open structure, certainly compared to schools.

It might be worth considering the example of the recent red flags that have gone up in UK universities where the apparent slackening of the grid has brought about what seems to be an epidemic of sexual predators – what is the truth behind the reported stories? Why has it been proposed that undergraduates have to have ‘consent training’ etc? [5] Is this a failure of the system, or an inevitable malaise unwittingly constructed by the system itself?

On top of this you have to ask yourself, do these young people have everything they need to survive and thrive, to navigate the bigger open-mesh of society and stay out of harm’s way? Has their education and upbringing given them the necessary tools?

They seem to lurch forward into the adult world with their parent’s words of warning ringing in their ears; but the irony for parents is that a mother’s advice to her teenage daughter as to how to stay safe on a Friday night out with friends is often based on what it was like in the 1990’s, so unless she’s got a time machine, it’s not going to be very helpful. The world changes at a phenomenal rate.

Not all grids are the same.

The societal structures (the grid patterns) are not the same all over the world; yes, they deal with the same basic issues of safety and rules but, for example, the gridlines in Birmingham UK are very different from Tijuana Mexico. (Or even Sarasota Florida).

A cautionary tale about grids.

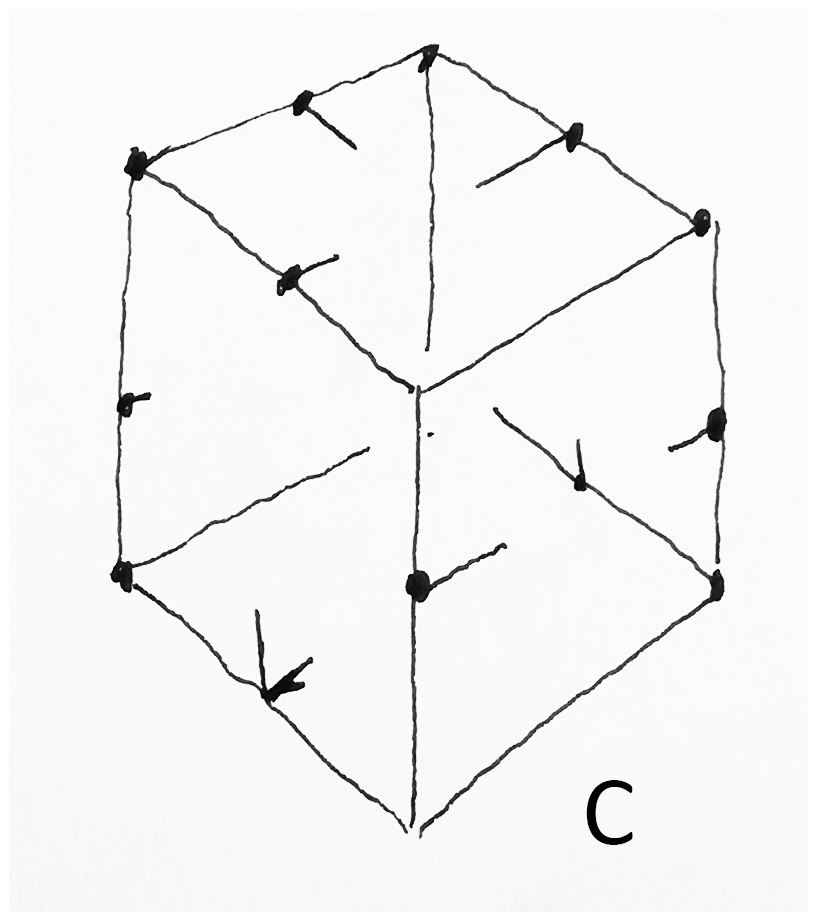

In 2011 two young British men, James Cooper 25 and James Kouzaris 24, while visiting Mr Cooper’s parents in Sarasota Florida decided to cut out on their own after an evening meal out. They were more than a little drunk, and wandered into a run-down part of Sarasota, a place called Newtown. It appears that Newtown is where the gridlines run out of road.

To cut a long story short, Cooper and Kouzaris were found dead at the side of the road. They had been shot by local boy Shawn Tyson 17, there was no sign of robbery, they both had wallets with money and phones; they just strayed into a blind spot on the grid, one which the locals of Sarasota and Newtown would have surely known about. [6]

This scenario would be unlikely to play out the same way if they were stumbling around Surbiton or Guildford at two in the morning, because they’d recognise the situation, understand their options and be able to navigate the gridlines that were available to them, while calculating the potential of threat or risks inherent to that particular scenario.

Sadly, it is unlikely that any amount of martial arts or hands-on self-defence training would have saved James Cooper and James Kouzaris.

Final word on terrorist threats.

This is a classic case of ‘head says one thing, but heart says another’, but statistically you’d have to be pretty unlucky to get caught up in a terrorist attack in the UK. Yuval Noah Harari the Israeli historian describes terrorism as ‘a puny matter’ when compared to what happens in warfare. It is essentially all spectacle and theatre designed to stoke up fear, and it does, just think about the example of the emotional and human after-effects of the Manchester bombing in 2017.

Essentially, governments and media do the terrorist’s work for them, they supply the oxygen to these combustible situations, and unintentionally become the recruiting sergeants for the next generation of terrorists through ill-thought out knee-jerk reactions. But, as they know, you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t.

Read Yuval Noah Harari’s piece in the Guardian, for a good description of how this works at a rational level.

Keep safe.

Tim Shaw

[1] As individuals in the animal kingdom we make pretty lousy predators; we are not particularly strong, agile or bulky to survive on our own without the employment of weaponry, and even then we have to operate in packs to achieve any level of success.

[2] Columbine High School Shootings https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbine_High_School_massacre

[3] Most schools I have visited have ‘lock-down procedures’, some have interior door wedges with the fear of the possibility of an ‘active shooter’, and this is the UK not the USA. The UK has only ever experienced three school shootings and all of the casualties (bar 1) occurred in just one incident. Compare that to the USA, where between the year 1999 and 2012 there have been 31 school shootings.

[4] Radical educationalist professor Guy Claxton said that schools tend to be constructed on one of two models; the are either ‘monasteries’ or ‘factories’. ‘Monasteries’ have; authorities in gowns/robes with other robes/uniforms for novices and are based upon some vague notion of revelation, with a massive worship of ‘tradition’. While ‘factories’ have bells to end shifts and have the intention of turning out identical little ‘products’ and are judged by quality controllers (Ofsted, Performance management etc), they won’t admit it but they are really exam factories. I know this because for a long time I worked in a factory that was built on the ruins of a monastery.

[5] Consent training and even ‘Good Lad workshops’ in universities and colleges. See this link from the University of Cambridge https://www.breakingthesilence.cam.ac.uk/training-and-events/training-students

[6] Murder in Florida, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-17479559

You’d better hope you never have to use it – Part 2.

“Smash the elbow”, “tear the throat out”, “snap the arm like a twig”, “gouge the eyes with your thumbs”. I have heard these things said by martial artists during classes. But I find myself asking, how do you know? and have you ever done that? Have you ever used your thumbs to gouge out somebody’s eyeballs? And on top of that, how do you know you won’t freeze like a rabbit in the headlights? Or, how do you know if you have enough resilience (or lived experience) to be able to suffer a terrible beating before you get a chance to put in that one decisive game-changing shot?

Empirical evidence versus anecdotes.

Effectiveness, can you prove it? Can it be quantified in a scientific way? Is the data available?

Every martial artist probably has a dozen stories as to why their martial arts method is effective as a fighting system and none of these incidents ever happen inside the Dojo – how could they, it’s supposed to be a safe training environment?

I have my own ‘go-to’ anecdotes, but equally I have another set of anecdotes where martial arts practitioners have come unstuck – but nobody talks about those, least of all the people who it has happened to (understandably). [1].

Anecdotes may be fun to recount but all they do is muddy the water, they are too random to qualify as evidence. And, if you look at some of these stories in the cold light of day you often have to wonder about (a) their veracity, (b) which way the odds were stacked, (c) whether elements of luck or chance were involved; but one thing is clear, they cannot really be used as definitive proof that your system works, after all, the system is the system and You are not the system.

The anecdotes may suggest that in certain circumstances your chances of coming out on top in a violent attack might be slightly higher – but they could also suggest that you might come out worse (probably because of over-confidence, or an unrealistic evaluation of your own ability).

The problem with fantasy.

Now compare that to movie fantasies of physical confrontations. I cite two examples that come to mind.

The first being Tom Cruise as Jack Reacher, where Reacher takes a bunch of guys on after they offer him out from a bar ( link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hu1MtT_S3bc

The thing is, deep down, we all want it to be like that.

And then Robert Downey Jnr as Sherlock Holmes in a bare knuckles contest (link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-z5139CW1I

This last one is about as extreme an example as is needed to make my point that fantasy is fantasy. (To paraphrase Mike Tyson, ‘Everybody has a plan until they get a punch in the mouth’.)

The Sherlock Holmes example is akin to treating violence like a chess game – if I plan and think several moves ahead then my plan will bring about the downfall of my opponent…. wrong. When it gets to the ‘trading punches’ stage you have already entered the world of chaos, thus ramping up the unpredictability exponentially.

It is potentially fatal to confuse Complex with Complicated [2] and the zone of chaos is indeed Complex. This is why those who are supremely skilful at navigating the Complex world have to do it without thought, artifice or calculation, they are like expert nautical mariners in a tossing sea, who work on instinct, they have an overarching understanding of Principle, their skills are not a bunch of cobbled together tricks that they have memorised hoping for that moment to happen.

I know that there are critics of the Principle angle in martial arts (particularly Wado), usually they fail to understand it and ask, what is this ‘Principle’ thing anyway? I am tempted to reply with something like the Louis Armstrong quote about the definition of jazz, “Man, if you have to ask what jazz is – you’ll never know”. (See my blog post on ‘Fast Burn, Slow Burn Martial Arts’ for a clue as to how it works). These same people remind me of the ‘Fox with no tail’ a moral story from Aesop].

When people talk about ‘functionality’, ‘functional combative skills’, this has to be about effectiveness, surely? But You can’t talk about that without some form of measure, if there is no measure then it’s all opinion and as such, we can take it or leave it. The person who makes the statement can only hope that we trust their opinion as an ‘expert’, but again, an expert based on what experience; their ability (as proven) to ‘snap someone’s arm like a twig, or gouge their eyes out’? I realise that there are people out in the martial arts world whose whole authority rests on this issue and it’s not my place to call them out, particularly as I also have no experience of ‘snapping arms’ to support any claims I make, but just apply a little logic to it.

Of course, I reckon that if I take my opponent’s elbow over my shoulder and exert a forceful two-handed yank downwards I might be able to ‘snap his elbow like a twig’, but I doubt he’s going to let that happen without a hell of a struggle (unless I am Sherlock Holmes of course). Meanwhile, he has barrelled into me, knocked me on my back and is sat on my chest raining punches into my face, and then his mates join in to kick me in the head for good measure – elementary my dear Watson.

Looking for evidence in history.

I feel I have to address this one. Anyone who looks for evidence in history is on to a sticky wicket. History is notoriously unreliable. We know this because current historical revisionist methods are revealing that many things we thought were true may not be so. For example; everyone knows that it is the victors who write the history.

If we take our history inside Japan and Okinawa and we listen to serious, open-minded researchers, we find that some of the things we took for granted may well not be true.

To give a few examples:

- Zen Buddhism does not have the monopoly in Japanese martial arts, certainly karate is not ‘Moving Zen’.

- The 19th century Samurai were not the apex of Japanese martial valour and skill. Set that two or three hundred years earlier and you might be about right.

- Okinawan martial arts were not the result of a suppression imposed by Japanese Samurai; it was not that simple. Okinawan people were generally peaceful and society was well-structured, it certainly was not the Dodge City that some people like to suggest, it seems that the martial arts of Okinawa reflected this, an extreme martial arts crucible it certainly wasn’t, certainly if you compare it with what was happening in Japan between 1467 and 1615. I don’t point that out to discredit the Okinawan systems, it’s just an observation and there were exceptions, e.g. Motobu Choki, who certainly had his ‘Dodge City’ moments.

As time moves forward all we are left with is the mythologies, hardly something to judge the functional abilities of teachers who are long dead, so all we have available is guesswork, assumptions and opinions; not really scientific or objective. So, anyone who wants to hang their ideas on that particular hook would be wise to keep an open mind.

How would martial arts work in a defence situation? A proposition.

To answer this, I would speculate that there are several high-level outcomes that are possible, and none of them look anything like either the movie fantasy image, or the types of techniques that are, ‘a bunch of cobbled together tricks that have been memorised hoping for that moment to happen’ [3].

- The highest level has to be that nothing happens, because nothing needs to happen. The world calms down and order rules the day; chaos is banished.

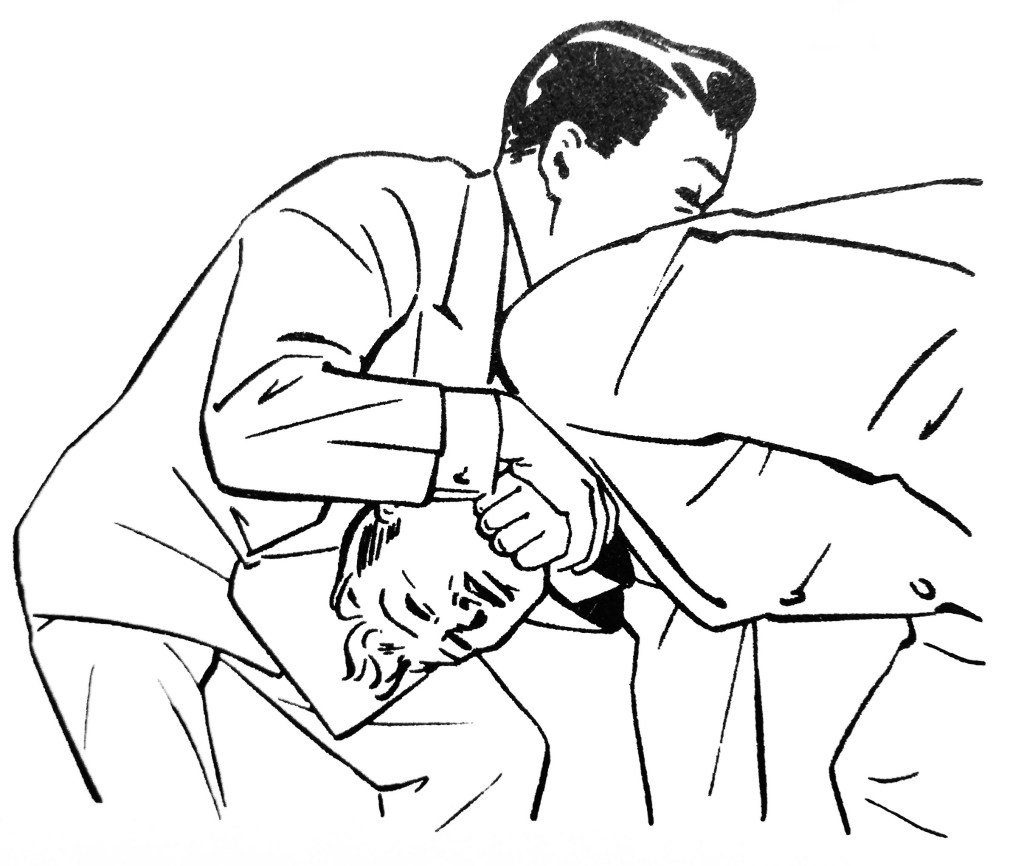

- The next highest level is probably where the aggressor just seems to fall down on his own. Here are my two nearest assumptions on this (one anecdotal and the other historical – but after all, I have to pluck my examples from somewhere). The first is a story about Otsuka Sensei dealing with a man who tried to mug him for his wallet in a train station. Otsuka just dealt with the guy in the blink of an eye and when asked what he did, he replied, “I don’t know”. The other is the historical encounter between Kito-Ryu Jujutsu master Kato Ukei and a Sumo wrestler who twice decided to test the master’s Kato’s ability with surprise attacks, and both times seemed to just stumble and hit the dirt [4].

- Anything below those two levels would probably involve one single clean technique, nothing prolonged, maybe appearing as nothing more than a muscle spasm, nothing ‘John Wick’, certainly nothing spectacular – job done.

- Then you might plunge down the evolutionary scale and have two guys smashing each other in the face to see who gives up first.

Conclusions:

The original objectives of these two blog posts were to challenge the assumptions we seem have made about the nature of self-defence (in its broadest interpretation) and to put forward some different angles, explode a few myths and to present the idea that all that glitters is not gold.

I don’t have the answers, but then it seems, neither does anyone else. But we shouldn’t just throw our hands up in the air. Keep on with the focus on defending ourselves and refining our technique and by all means teach self-defence as a supporting disciple or on dedicated courses, it is a brilliant way for martial arts instructors to engage with the community in a positive and confidence building way; however, keep it realistic and not just fearful.

For those who claim that their approach has more ‘functionality’ I would humbly suggest that that you might want to look towards the key questions; objectively, how can you prove that? Maybe what you are asking for is a leap of faith? My view is that the data is not there and that it is just lazy logic. [5]

There are people who want to claim their authority from the ‘short game’, while I would suggest that there is another game in town; the ‘long game’. Targets really need to be aspirational and ambitious, not ducking towards the lowest common denominator, i.e. the ‘fear factor’ of the anxious urbanite. Your authority is not derived from your ability to ring the metropolitan angst bell; or to yank the chain of the frustrated metrosexual male who feels he is cut adrift and fretful about his role in contemporary society and lost in a maelstrom of surging confusion.

The bottom line is; get real and dare to think differently.

As a last word, these posts are not meant to be definitive, or to cover all aspects of self-protection. I could have included comments about how the law views self-defence, or how much mental attitude is a part of self-defence, or adrenalin, fight and flight etc, without even mentioning the number of young men in the UK who die through stab injuries. But maybe another day.

Tim Shaw

[1] One event happened fairly recently where I had bumped into a martial artist from another system, an acquaintance, in a nightclub. He’d had a drink or two and proceeded to bend my ear about how ‘the trouble with most martial artists is they have never been in a real fight, never trained for it, etc.’ And, as if the God of Irony was looking down upon him; within seconds of him waving me goodbye, he crossed paths with the wrong person and ended up as a victim, laid out and bleeding. I guess he didn’t get the chance to ‘snap the arm like a twig’.

Be careful what you wish for.

[2] See my blog post on Systems. https://wadoryu.org.uk/2020/01/29/is-your-martial-art-complicated-or-complex/

[3] These methods often assume that the opponent is going to present themselves like a bag of sand and allow you to engage in an ever-complex string of funky locks, take-downs, arm-bars etc. etc. Sherlock Holmes would definitely approve.

[4] Source: ‘Famous Budoka of Japan: Mujushin Kenjutsu and Kito-ryu’. Kono, Yoshinori, Aikido Journal 111 (1997). According to Ellis Amdur in his book ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’ this is pure Principle and Movement in practice (my paraphrase).

[5] Similar to the way people talk out about ‘life after death’, i.e. how do you know? Conveniently, nobody has ever come back to tell us. Ergo; you never have to validate your claims.

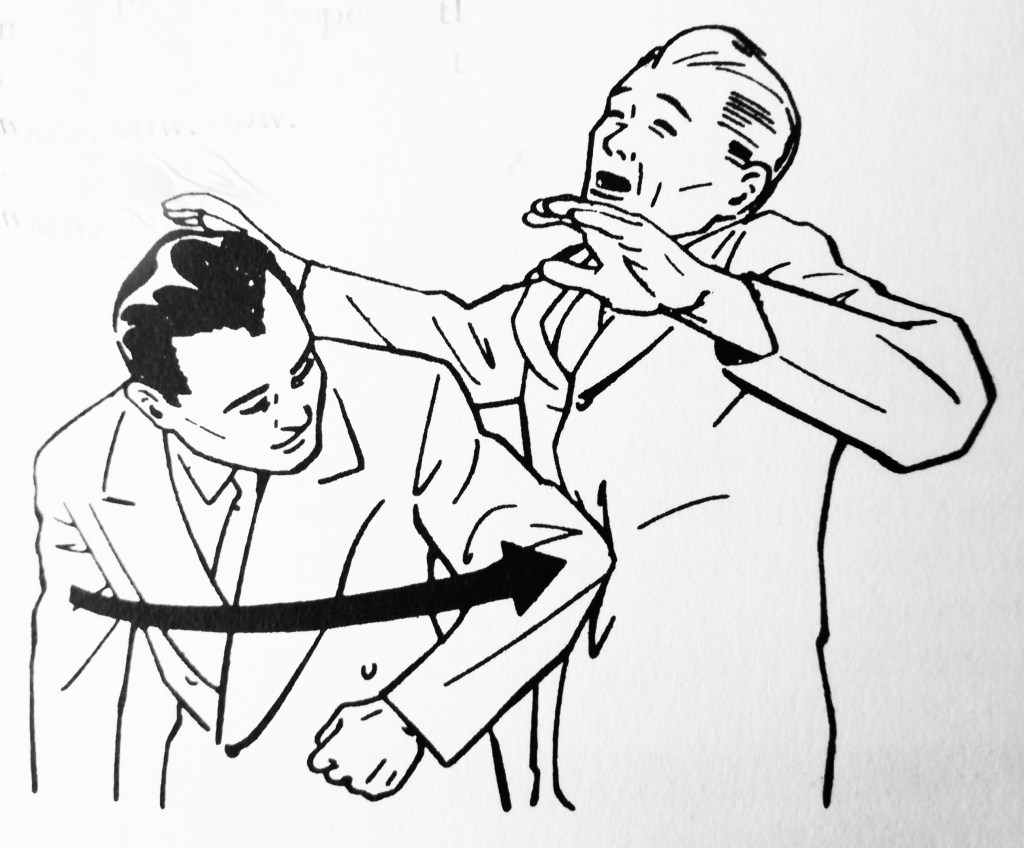

Image credit: Kiyose Nakae ‘Jiu Jitsu Complete’ 1958.

You’d better hope you never have to use it – Part 1.

An alternative view on self-defence and ‘effectiveness’. I have been thinking about this for a long time now. Every time I see this subject brought up on martial arts forums, I find myself shaking my head; where is the objective clarity? Where is the cold scalpel of logic which is needed to cut through the mythology, pointless tautology and hyperbole? In addition, why doesn’t someone call out those who are too quick to erect a whole forest of straw men; those who set up false equivalents and apply simple answers to complex questions?

Self-defence, what does it even mean?

Taken at face value it’s supposed to be our raison d’être, but we know that Japanese Budo has worked hard to raise itself above primitive pugilism, and the inclusion of firearms into the mix has brought in an element of semi-redundancy, particularly in certain societies around the world. But we still have the hope that we can take the ethical and moral high ground through the philosophies of Budo, which, in itself is not above hyperbole (try, ‘we fight so that we don’t have to fight’, I know what it means, but I suspect I am in a minority).

Real Violence.

We tell ourselves that we are training so that we can protect ourselves against physical attacks by unknown (or even known) aggressors who clearly mean us harm. Realistically, most people have fortunately never really experienced that (here in the UK, despite what the papers want to tell us, we live in quite a peaceful society [1]). Hence, what people do is carry around an image in their heads of what that violence may look like; but, based on what exactly? Mostly, I suspect it’s a mish-mash of choreographed movie violence and random CCTV footage on YouTube; it is highly unlikely it will be based on real experience.

What does real violence look like?

I don’t like doing this but unfortunately, I have to base my proposition on a degree of personal experience, mostly (but not exclusively) from my younger days.

A list of what real violence tends to be:

Random, irrational, devoid of humanity (and often bereft of conscience), chaotic, usually spontaneous, ugly, seldom prolonged (most likely, over in just a couple of seconds), all too often cowardly with any elements of restraint removed by the effects of alcohol or drugs. Not in the least bit glamorous and hardly anybody comes out of it as a hero, and certainly nobody calculates the consequences of their actions.

It is this last one I want to look at in a little more detail. (Here’s where ‘You’d better hope you never have to use it’ comes in). I’ll start with; if you make a decision to punch, kick or elbow someone in the head, you’d better be prepared to live with the consequences.

One thing that tales from news media can tell us quite graphically and accurately, is the results and the aftermath of a physical assault; whether it is initiated by the aggressor or the defender, it doesn’t matter, James Bond or Jason Bourne never have to give a thought to the ‘bad guys’ they ‘take out’ in a fist fight, and neither are we, as an audience, expected to; the plot just rolls on. But that is the fantasy.

Read this account of a 15-year-old boy attacking a man with the so-called ‘superman punch’ resulting in the man’s death https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jul/25/polish-man-arkadiusz-jozwik-killed-superman-punch-court-hears

Lives ruined, families traumatised and all for what?

Someone once pointed out to me that all those techniques that are most effective in so-called self-defence situations can result in life-changing injuries and will most likely cause you to end up in court.

Please don’t misunderstand me, I am not advocating passivity or a total abrogation of responsibility, just a balanced grown-up attitude as to whether one is prepared to go for the so-called ‘nuclear option’ or not [2].

Practice and Theory.

As regards teaching self-defence classes; there is a wonderful contradiction worth considering. Nobody in the history of martial arts has EVER argued that theory has value over practice, but maybe in terms of practical, realistic self defence it does?

It is possible that if measured on results alone the value of theoretical knowledge of personal protection may outweigh that of learning hands-on physical skills.

When I designed my own self-defence courses (outside of the Dojo environment) I always factored in a theoretical aspect; a sit down and talk and explain. This would cover such things as, threat recognition, de-escalation of aggression, awareness, specific grey areas, psychological indicators and basically heading things off before they became a problem. All of these things I have NEVER taught in the Dojo, mostly because we just don’t have the time, and I suspect I am not alone in making that admission; but how ironic, here we are as martial arts specialists and we don’t have the time to put in these very important elements. [3].

The cynical exploitation of the fear factor (Self-Defence as a business opportunity).

I get it, everybody has to make a living. But maybe we should draw the line at people who feed off the fear of others. In this we find the worst excesses of the self-defence ‘industry’. Please don’t misunderstand me, most people who teach self-defence are well-intentioned and probably do a really good job, but a red flag for me is when they press the ‘fear’ button, because they deliberately feed off the darkest nightmares of the anxious urbanites. For the worried town dwellers, the fear is real, but it may well be a product of a wider malaise, an existential crisis marked by alienation and the decline of community, as well as the cult of the ‘self’; (‘me’ rather than ‘us’).

I am convinced that there is both a male version and a female version of this fear. The female version is of course very real and is wrapped up in the complex world of the politics of the sexes and goes back thousands of years. I wouldn’t even think of beginning to understand that, it’s a real tiptoe through the minefield and seems to be getting worse rather than better.

The male version is easier to understand.

There is a profound identity crisis going on with young males; they just don’t know who they are and this often affects their views on how to respond to aggression or threats from other males [4]. Tradition and history say one thing; a view that is supported by biology; but contemporary society says that there is no need or place for antelope hunters and skinners or people wielding big heavy swords like Conan the Barbarian. I am convinced that a secret desire of most males is for the advent of the zombie apocalypse, just to give them an excuse to use that baseball bat kept near the door ‘just in case’; an adolescent male fantasy. [4]

But, to return to the idea of the ‘cynical exploitation of the fear factor’. I am convinced that some of the people who have found a niche in trading off urban anxiety have been (in part) influenced by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (you might find it mentioned in books on modern marketing). If you can convince people that their fears are justified and that their whole existence is under threat in a decaying society, and your solutions will act as an antidote, they will come flocking to your door and you’ll be laughing all the way to the bank.

Am I arguing against the teaching of self-defence?

The answer to the above question is a resounding ‘No’.

As far as I am concerned, when I have taught self-defence courses it made me feel that I was actually giving something back to society, and feedback received said that some of the knowledge gained actually helped people out of some sticky situations, so another feelgood factor. It is stripped back martial arts, a bit like stripped back First Aid courses, it might give someone the confidence that they need in an emergency, it might save somebody’s life. Every little helps.

The fuller argument will be fleshed out in part 2.

Tim Shaw

[1] It would be much more objective if people would at least consult the statistics.

- Most people are murdered by someone they already know.

- Young men are in greater danger from random stranger attacks than young women.

- Terrorist attacks are so rare that it is inevitable that they hit the headlines and achieve their warped objectives of setting up ripples of fear through the population. As an example; In 2001, road crash deaths in the US were equal to those from a September 11 attack every 26 days.

[2] ‘The Nuclear Option’; a willingness to take things to the most extreme end of the spectrum, even if it means your own destruction. I.E. no serious world leader would ever admit to be willing to press the nuclear button; it’s just admitting to a form of suicide that embroils all the people you are responsible for into your own folly.

[3] Isn’t it odd to think that there are people in the martial arts community who consider kata a waste of time and compare it to the comical practice of ‘land swimming’, as opposed to swimming in water. Yet here we have a ‘land swimming’ example which maybe does work. Or perhaps that in itself is a false equivalent, as this isn’t really ‘land swimming’, it’s more akin to getting advice from a lifeguard about rip tides and safe swimming zones – which will possibly save your life and keep you from drowning?

[4] There is a section in a book I would recommend, ‘The Little Black Book of Violence’ by Kane and Wilder, which asks the question, ‘is it worth dying over a mobile phone?’. The answer is clearly ‘no’, but in the heat of the moment… Also, I do remember, years ago, an ad in martial arts magazines, which featured a photograph of some kind of glamour model with the headline, ‘Could you protect your girlfriend?’.

Image credit: Kiyose Nakae ‘Jiu Jitsu Complete’ 1958.