The Politics of Paired Kata Part 2.

In this second part I will attempt push further beyond the boundaries of the standard workings of the paired kata in Wado karate. I am not expecting everyone to agree with me but please bear with me.

The Contract.

In Japanese Budo what I am calling ‘the contract’ is really important. You are measured and judged by your ability to assiduously, almost pedantically, stick to ‘the contract’.

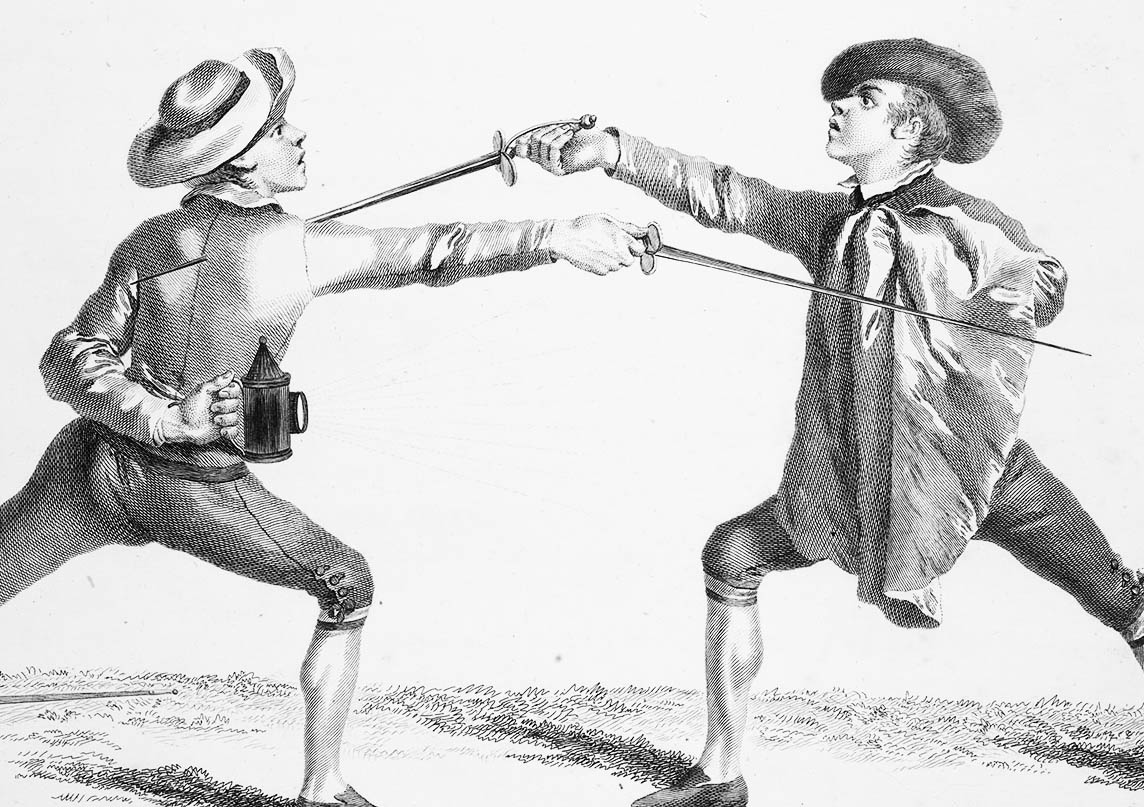

This manifests itself beautifully, almost poetically, when it comes down to working with bladed weapons. One mistake, one ill-considered move or lack of intent and things get messy really quickly.

Consider the Tanto Dori (knife defence) paired kata of Wado Ryu. Uke has the blade, knows his role and not only sticks to the script but also delivers the blade as powerfully and accurately as he is able. Tori knows this and as a result his focus becomes hyper-acute; it has to be. He can’t move early (a clear betrayal of the contract) and to move late is potentially fatal. There is only one option; get it right!

How we got away with that in the late 20th century is a source of amazement to me – today, ‘health and safety’ would have been all over it!

But it has to be remembered that the paired kata are teaching tools. Yes, they are formalised, but as such they are the embodiment of wisdom refined over generations. I know that some may wag a judgemental finger and say, ‘but that’s not real, that’s not what would really happen!’ and of course they would be completely and spectacularly missing the point.

A Conversation.

To return to the theme of kihon gumite – if you look across the ten canonical kihon gumite and try to see them through the lens of a protracted sequential dialogue, then the wisdom and cleverness of them just leaps out at you.

Sequentially, they open up a series of overlapping conundrums and a shed-load of ‘what ifs’. I won’t go into them individually, but they offer themselves up like a puzzle box, where positives mesh with negatives in time and space. This is the ‘politics of paired kata’.

Looking at the paired kata as conversations between two protagonists; as we know, conversations come in many forms; not all of them are meaningful or even useful. Some conversations are clear in their intentions; others mask duplicity and deceit.

There are conversations (if indeed they can be called that) where one party harangues another; spouting their pet theories, looking for validation, shooting down any dissent, seeing the other party as an antagonist, not listening to counter arguments, etc. The kihon gumite version of this is where either party disregard the other; just doing their thing. It’s an empty experience for both sides, a total waste of time and energy.

High level conversations.

And then there are high quality conversations; ones where nobody is trying to score points, where opinions are speculations and not carved in stone and both parties have a common cause and listen respectfully. These are truly exploratory exchanges; all parties involved on the cusp of their knowledge, open-minded, aware and unafraid to venture into the unknown, while maintaining the solid foundations of a mindset which is matched to the task.

Within paired kata like the kihon gumite, both protagonists approach the engagement (conversation) respectfully and almost with an air of reverence. Their focus is complete and directed at all aspects of the unfolding sequence of events. They know there is a script but they don’t allow themselves to become totally straightjacketed by it. There is nuance and a battle going on inside the battle, observing keenly the micro-gestures; (whether they are aware of it or not), very much like meaningful and positive verbal exchanges.

Different styles of conversations – successful, or not so successful?

It is said that conversations are generally more successful when conducted between peers and rarely so when directed from the middle or bottom of a hierarchy upwards, as in, an under-manager upwards towards a senior manager or boss. It can be tricky because of the hierarchical positions; the underling has to approach his boss with great care for fear of stepping over the line, or seeming to criticise or undermine decisions or ideas.

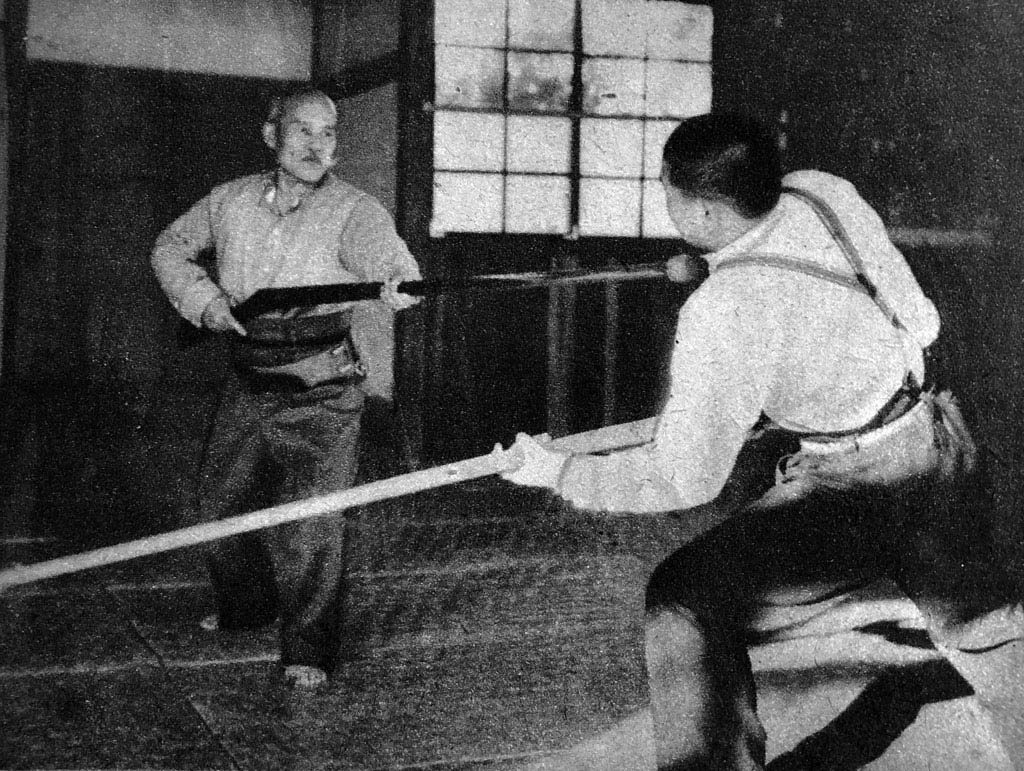

But the same situation in paired kata can have a useful dynamic; because; if the junior is open and receptive, they can gain so much from working with a senior grade. Direct physical communication relating to issues like body feel, timing and cause and effect, these aspects almost bypass the intellectual and go right to the heart of the matter; tapping into that weird level of consciousness that exists as what Ushiro Kenji calls the ‘Body Brain’.

There may be more to this than we think.

The politics of paired kata could possibly have more complexity than appears at first sight.

The general understanding is that these kata are seen as sets of prescribed techniques that are linear and ruled by cause and effect, i.e. ‘In response to this attack, my response is…’. This generally fits in with how the physical world operates, or rather how we prefer it to operate; in a very predictable way, it’s comfortable for us. As an example; if someone climbs a high stepladder and drops a golf ball they can pretty much tell you to the millimetre where the ball will impact on the floor. Try the same thing with a piece of paper and, although you know it will eventually hit the floor, you can’t be sure exactly where. In a way, it is comparable to dealing with someone’s direct physical aggression, a random attack; you really don’t know how it’s going to play out. Here we can see the weakness of being bound by linear thinking.

Cause and effect; action and reaction follow a very comfortable pattern of Newtonian physics. For some schools of karate and certainly the so-called ‘Reality based Self-defence’ this is all that is needed, and the simpler the better.

But if you dig deeper, it all goes a bit Schrödinger’s Cat.

There are some tantalising conundrums in the paired kata that lean towards the same kinds of qualities and contradictions found in quantum physics and become a challenge to the Newtonian model [1].

Contradictions.

Examples of contradictions in Wado:

In the Wado paired kata these puzzles are sometimes presented to us overtly.

The second grandmaster would tease us by talking about ‘Wado mathematics’, he would say, “It works like this; in Wado it is 1 + 1 = 1”. How can that be so? Once you see it, it all makes sense, and it sets the bar really high if you want to work it at the physical level.

Another wonderful contradiction is that Tori and Uke are separate, but one. This is very ‘quantum’, the contradiction to the Newtonian form of action and reaction; in the quantum world action and reaction are one and the same, you are not waiting for things to happen, you are not waiting for feedback, you ARE the feedback, you are making your own reality. What happens between Tori and Uke is also an embodiment of a mutual resonance; there is a harmonic interplay which dissolves the convenience of thinking of these roles as separate entities.

Added to that is that the ‘attacker’ and ‘defender’ can be both at the same time! The river flows on and reality changes – like Heraclitus says, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.”.

This does away with the idea that Uke is a mere stooge, operating with dumb passivity; a punchbag for Tori to work his magic on.

This is why in Wado the oft-used platitude of ‘Karate Ni Sente Nashi’ (‘there is no first attack in karate’) becomes meaningless to us. It has uses and meaning to the Okinawan branches of karate, but in Wado it is a retrograde method. Japanese Budo has a more refined approach to cognitive reality, completely at odds with the morally ‘safe’ perspective of Okinawan pragmatism. The Okinawan moral standpoint is secure and (for them) unquestionable, but for me it is philosophically unadventurous.

The root of these contradictions is not unique to Wado. Many examples can be found in the older Japanese Budo.

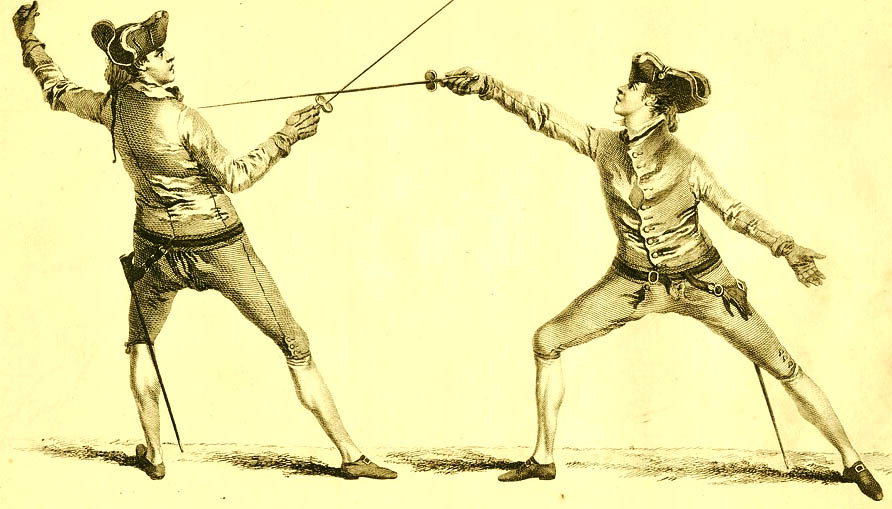

Koryu practitioner and author Ellis Amdur describes the contradictions found within the Itto Ryu school of swordsmanship; specifically, the technique Kiriotoshi (dropping cut) “in which two swords cut along exactly the same path…”.

Amdur makes no bones about it, “Kiriotoshi accomplishes the seemingly impossible – apparently defying Newtonian physics. At the moment of impact, with two objects – swords – occupying the same space. One ‘passes through’ the other. This is the product of one individual who is striking with a sword meeting another who ‘is’ a sword. Literally, the sword and body are one entity.” [2].

Conclusion.

It is sad that some of the most valuable aspects of paired kata get lost in the weeds. In this case the ‘weeds’ are the positional minutiae; where this foot goes, or that hand goes – all of which are important of course, but it is a mistake to think that this is all there is to it. If your objective is doing it faster, harder and stronger, and making great shapes, then eventually you would meet your ceiling, as many do. And to assuage their deep-seated and largely subconscious worries that maybe that is all there is to it, they might feel inclined to just pile on more paired kata and kid themselves that this is progress – when all along all that’s needed is adherence to core sets of principles. It is these same sets of principles that become the fertile ground from which an unlimited range of technical options spring. Get them right and it becomes truly effortless (or so I am told).

Working with principles is like jazz musicians riffing on a theme and exploring each appropriate path of musical possibilities, always in step, even as new options unfold, beyond thought, beyond artifice; the music is almost a power outside of them.

I am tempted to appropriate a quote from the great jazz trumpet genius Miles Davis and apply it to options thrown up within paired kata; that is, “It’s not the note you play that’s the wrong note – it’s the note you play afterwards that makes it right or wrong”.

For me, the spirit of that quote works well with the politics of paired kata.

Tim Shaw

[1] I lay no claim to being an expert in the field of physics; please don’t bombard me with harsh and incomprehensible brickbats. I am only an amateur.

[2] Ellis Amdur, ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’ 2000 edition.

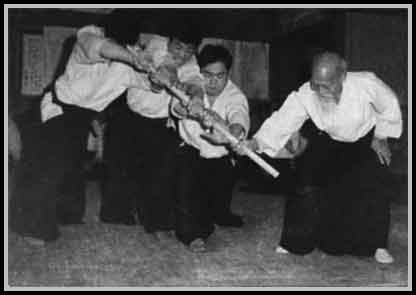

Featured image; Tim Shaw and Martijn Schelen working on Tanto Dori.

The Politics of Paired Kata Part 1.

In this two-part blog post I want to suggest different ways of looking at our paired kata; whether that is kihon gumite, kumite gata, ura no kumite or ohyo gata.

Decades ago, a well-known western martial artist and writer had a chance to observe Otsuka Hironori, the original grandmaster first hand. The writer was from a different martial arts background not a Wado stylist. He wrote at the time that the ‘real’ kata of Wado Ryu were the paired kata. To my mind, either he was being deliberately provocative or he only assumed everyone would look at the context of kata exclusively in solo performance and neglected to draw connections between Wado solo kata and Wado paired kata.

To him the paired kata were clearer and more accessible. It is understandable in a way; particularly when you see what solo kata is currently evolving into, through the athleticism and drama of Olympic sports karate kata.

I am fairly sure that regular readers of this blog don’t need to be reminded of the root origin of the Wado paired kata [1]. These were never intended to be just sets of shallow two-man drills; they were meant to be understood and practiced as repositories of knowledge, containing layers of information in various forms.

It is these very same forms I want to speculate on in this two-part post.

Why did I refer to it as ‘The Politics of Paired Kata’?

When I am teaching paired kata I often explain what’s going on by referring to, “the politics of kihon gumite (or kumite gata etc)”. However, for the sake of simplicity ‘kihon gumite’ is one of the most convenient examples because it often contains the more complex but overt examples of ebb and flow and interchange that will perhaps support my argument.

Bear with me on this. Put simply; it is said that whenever you get two people in a room, politics is always playing out. For anyone with a keen eye its manifestation is obvious and subtle at the same time. Formal greetings, posture, position, proximity, eye contact and possibly small-talk which may lead on to serious discussion or even disagreement are all there to be observed.

There are rules at play, it’s all ‘political’ (with a small ‘p’). Add to that social niceties, protocols and good manners; everyone plays by the rules, you have to, because these same rules oil the wheels of society. Some might say that rules constrain us, tie our hands, and maybe they can become overly stifling – for example Japanese social rules are much more regimented than western European ones are.

The expectation is that all parties agree to follow the rules.

Rules are important.

As an example:

Imagine you are going to teach someone to play chess. They ask you what the objective of the game is? Your reply, “Simple… Your job is to take my king”. To which they then reach across the table and snatch your king off the board, hold it aloft and say, “I win!” By doing such a thing they achieve the logical objective (initially outlined by you) but the complex rules of the game in its entirety facilitate an opening up of amazing mental gymnastics and seemingly endless possibilities. So it is with paired kata.

In kihon gumite you have tightly prescribed roles with attached responsibilities. That is really your starting point. You know the rules – now live up to them and doors will open…or not.

What can go wrong.

Here are two examples of the rules falling apart in Wado paired kata; one more dramatic than the other, but in their own way quite revealing.

The first one is on a grading somewhere in the East Midlands around 1976.

Two girls were taking a kyu grading in front of Suzuki Sensei. Everything went really well until it came time for the paired kata; Suzuki Sensei’s three step kata, sanbon gumite.

One of the girls (the attacker) thought the punch should have been to jodan, but the defender, for reasons known only to her, blocked low; the result was that she took a full contact punch in the face. There was a lot of blood. The girl who delivered the punch was mortified that she had inflicted such damage, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry”, she spluttered, clearly distressed and powerless to do anything about it.

Suzuki Sensei sat at the table initially impassive, and then he stood up and railed at the girl for apologising! “Why are you apologising?” “it’s not your fault; it’s her fault!” he yelled, gesticulating at the girl with the bleeding mouth and nose.

Eventually, the club instructor stepped in and cleared the situation up.

It’s clear, if you operate outside of the agreed rules (deliberately or accidentally) all the wheels will come off.

The second example is not so catastrophic but it didn’t make it any less significant and, in this case, annoying.

For this one, I can guess that all of us have come across it – and, for that to be true, many of us will automatically have been the perpetrators of this particular crime… (but will never own up to it).

The crime is, being guilty of delivering a lousy attack.

The first time I came across this in paired kata was during the practice of Suzuki-ha sanbon keri uke (usually the last kick). Uke, knowing his kick was going to be swept aside, would stupidly and obligingly aim off target and swing it across himself! Deliberately off-line, meaningless, counter-productive… pointless; a parody. Nobody gains anything.

There are so many forms of this criminal disregard for protocol.

A friend of mine, a very able senior Dan grade (from one of the other organisations) told me how he came across a variation of this on a major course.

During the practice of kihon gumite with another Dan grade, (who really should have known better), he had to face an attack that in reality would have never made the distance. Instead of just going through the motions and obligingly allowing this pantomime to play out, my friend just stayed where he was, and as the attack fell short, he said, “What are you doing?” It is not really a polite response, but I would challenge anyone in the same situation to have behaved differently.

All of these are examples of the contract being broken.

I will discuss ‘the contract’ and other aspects in part 2.

[1] Because of Otsuka Sensei’s background in traditional Japanese Budo (he began his Jujutsu training under the age of eight and continued all the way through his twenties) he understood the long-established teaching method of paired kata, both armed and unarmed. He knew that as a vehicle for transmission this methodology had considerable value, particularly if the intention was to impart layers of established strategy, technique and wisdom. The kata were codified reflections of refined wisdom and the purest form of Principle (Ri) and not intended to be pure embodiments of refined, spontaneous active and living ‘Ri’. As such they were classified as ‘Ji’. (reflections, exemplars, models to reveal how ‘Ri’ manifests itself).

Featured image; Tim Shaw with Sugasawa Sensei explaining kihon gumite in 2017.

Tim Shaw

Has modern movement culture got anything to offer martial artists?

About two years ago, by complete accident, I discovered the work and philosophy of Israeli movement guru Ido Portal. I have found him a source of inspiration ever since, particularly through working on my own training during the lock-downs.

I know the concept of ‘movement culture’ has been around for a long time, but the work of Ido Portal and others has put it on a different level, with a newer definition.

Normally, human movement has been focussed on specific aims, ultimately leading towards success in such things as sports, dance or martial arts. As martial artists, working with our bodies is what we do and movement for movement’s sake would seem like a preposterous idea.

We martial artists are surely supposed to be aiming to be specialists; but here’s the news; Ido Portal hates specialists! (more of that later).

If you search YouTube for ‘Ido Portal’ the first thing you’ll find is that Ido can do things that most people can only dream of. Part gymnast, part acrobat, part dancer and… dare I say it… part martial artist. However, I suspect that not many people will get past the twirls, spins, one-armed handstand balances and lizard crawls; it is truly amazing, it’s Ido’s shopfront.

But in a way it’s all confectionary; it’s a distraction; even Ido himself admits as much; he openly dislikes the fact that this is how people view him, and how this side of his work is like catnip to exhibitionists and extroverts. He wants people to look beyond – and for martial artists this is where the really valuable stuff is.

But then for us as martial artists, this is where we encounter the second hurdle to get over.

Ido Portal and Conor McGregor.

His media output trumpets another aspect of the Ido magic. Wasn’t this the same Ido Portal who UFC fighter Conor McGregor worked with to prepare for his fight with Jose Aldo? (The one in which McGregor took the much-favoured Aldo out after only three punches had been thrown). Yes it was.

Oddly, Ido took some flak for that, but only from people who didn’t understand his ideas. The rather conservative UFC community poured scorn on Ido’s training methods and snorted disdainfully that Ido and Conor in their training had been playing, “touch butt in the park”. How wrong they were.

Look beyond the McGregor thing; listen to some well-informed detailed interviews with Ido. I can recommend the ‘London Real’ mini documentary on Ido Portal by Brian Rose called ‘Just Move’. It’s a good place to start. Also, the Coach Micah B Interview with Ido Portal ‘Touch Butt in the Park’. Micah, as a martial artist, asks a lot of the questions that intelligent martial artists would ask.

Origins and development.

As you look into his backgrounds and the beginnings of his developing ideas you will see that it really started for him within the Brazilian art of Capoeira. Ido was clearly looking to go beyond and dig deep into the study of movement. In a way he seemed to me to embrace the magic and methodology that Elon Musk brought to the examination of technology. Musk’s secret ingredient, borrowed from Scientific ideas, is called ‘First Principle Thinking’, and Ido Portal did almost the same thing, going right back to the very source of human movement. Ido Portal studied hard, both through theory and practice and travelled all over the world (If you want to look at some of his sources, you wouldn’t go far wrong reading up or watching videos about coach Christopher Sommers).

Ido’s opinions on ‘specialists’.

What is it that Ido Portal does not like about specialists? This, surely puts all martial artist in the firing line?

To him a specialist is, by definition, a physically limited individual, who within their narrowed field ends up painting themselves into a corner. They are not developing the fuller scope of what their body is capable of, they are wilfully limiting themselves and existing within their own physical echo-chamber.

The good news is that the solution comes in many flavours, and ones which we would not find wholly unpalatable.

Firstly ‘learn to fail’. It is a truism that the zone of failure is the zone of growth. Traditional Chinese martial artists make much of the phrase ‘invest in loss’, this is another branch of the main idea. Not to get too poetical about it, but to grow we must dance the line between order and chaos (credit to J. B. Peterson for that one).

Ido is mischievous in his attitude towards the specialist. The reality is that from his perspective the fully moving, exploratory approach has to either come first or, as with McGregor, become a part of the overall training regime.

Some disciplines/specialisms from Ido’s viewpoint show very specific weaknesses. For example, Yoga he says, has no hangs, no suspension and ‘held’ positions are deemed paramount to the practice; Ido thinks that this is counter-intuitive.

‘Expertise in only one area sets up an habitualised body’, from Ido’s perspective the body is designed to take strain from all directions. This is not to say that we cannot work towards efficient body movement; this is what we try and promote within Wado. We also know that there are such things as movements which create bio-mechanical weaknesses; knees and backs pay the price of injudicious movements; but we also know that we should be looking to explore our fullest ranges of movement.

Agency.

This is why Ido Portal despises the title of ‘guru’, he is not a ‘guru’. He very much believes that anyone on such a personalised quest must have agency and take responsibility for their own development. He says that nobody should hand over the keys of accountability to another person – own it!

This chimes with my own thinking. Sometimes I meet people who are able to recognise something of quality but are unwilling to put in the work, or believe that the magic only happens when Sensei is in the room; another way of abrogating the responsibility away from the individual; a ‘get out’ card.

Having said that, Ido believes that if ever you meet a real master you must seize what is offered with both hands.

Listen to the wisdom of your own body.

I know I have written about this before; specifically, in the context of the older martial artist; relating to a kinder, balanced approach to your workload; knowing when to allow your body recovery time.

Ido Portal actually suggests two negatives to be aware of. The first being this same error of injudiciously punishing your body and foolishly accumulating long-term damage.

Once, in conversation with a Japanese Wado Sensei (who no longer lives in the UK), over his pint he lamented the training methods we were put through in the 1970’s and 1980’s, “The body can’t take that amount of punishment for long, eventually it will catch up on you” he said shaking his head.

Ido Portal’s second negative is not enough movement. This is an even bigger problem, mainly because it is so insidious and difficult to guard against, it sneaks up on you and you are just not aware of it. This recent lock-down experience for many has let the devil down the chimney. It’s so easy to let atrophy set in, and the damage is done and you won’t even know it until it’s too late, and even then you will probably let the real thief off the hook and blame something else, ‘Oh, it’s my age’, ‘Oh, it’s my underlying conditions, my genetic disposition’ etc, etc, and so the list goes on. Ido really does believe that ‘motion is the only lotion’.

Basic beneficial practice that anyone can do.

Ido Portal strongly recommends two exercises that if built up over time can have surprisingly positive effects.

Firstly; just squatting on your haunches; it’s actually what we were built for and we robbed ourselves of the benefits by inventing chairs. Thirty minutes every day, and not even thirty consecutive minutes, five minutes here, five minutes there is enough. The positive effects on this will be a beneficial manipulation of the back and pelvis, as well as the knees and ankles. There are additional bonuses which impact on digestion.

The second exercise asks a little more in terms of equipment or situation, and this is just hanging from a bar; no pull-ups, just stretched out and extended. There are so many benefits including counteracting the accumulated effects of gravity on your structure. In both exercises we are actively (or passively) working around gravity.

Why failure can be a positive thing.

Although failure can sometimes be a crushing experience, there is so much to be gained from exploring the zone of failure. Often, we find that failing to do something encourages growth (as the Stoics said, it’s the attitude we chose to adopt after failure that tends to chew away at us – and it is a choice).

Ido worships at the shrine of failure.

A typical Ido Portal ‘failure’ challenge.

This involves taking a tennis ball, throwing it against a wall and trying and return it with your fist; see how many times you can knock it backwards and forwards. It’s not impossible, just challenging, and you will fail over and over again.

Eventually you will experience some success and may even get good at it, but, if you reach that point, you may as well stop, because the objective is not to get good at it; the objective is to explore that zone of challenge and failure. That one practice teaches you so much about your body; about adjustments, coordination, control, spatial awareness, footwork and a whole host of other things, and also teaching you something about yourself and your mental attitude towards challenge. It is essentially a growth experience and we as human beings should be engaging such experiences both physically and intellectually.

Conclusion.

Conor McGregor was a smart man in engaging the services of Ido Portal. Short snippets of the training practices show how eager McGregor was to take on board Ido’s ideas; commentators and opponents said that it was clear that his style of movement changed.

Ido Portal’s journey from martial arts to pure movement is an excellent exemplar of the evolution of human ideas manifested through the physical mode. This is high-brow physicality, and to my mind it is not at odds with the more sophisticated martial arts; specifically, where there is such a high demand for self-knowledge and body awareness.

Tim Shaw

Ido Portal, Image credit; London Real, Brian Rose.

Martial Artists Past and Present.

What did the martial artists of the past have that we don’t have today?

I don’t think it is possible to give definitive answers to this question, but it’s worth asking the question anyway.

There are many amazing and literally unbelievable stories about martial arts masters from the past, and some of them not so very far distant from the current age. For example; is it true or even possible for Ueshiba Morihei founder of Aikido to willingly stand in front of a military firing squad at a distance of about seventy-five feet and, at the moment they pulled the trigger, some were swept off their feet and Ueshiba ended up miraculously standing behind them! And just to prove a point, he did it twice! Shioda Gozo, Aikido Sensei says he witnessed this. [1].

Some of the tales from the more distant history are just as amazing.

Even if we take these stories with an enormous pinch of salt, stripping away the propaganda and the myth building, surely, there’s no smoke without fire? Two percent of that kind of ability would be more than enough. They must have had something?

It has to be said that the background to these kinds of stories is presented to us in a landscape that is so very remote from our own.

I suppose a key question is; is it possible for someone in the modern age, living a 21st century lifestyle to achieve anything like the semi-miraculous skills of the likes of Ueshiba Morihei in Japan, or Yang Luchan (patriarch the Yang school of Tai Chi) in China. Logically, if such skills exist, it may well be possible to attain such abilities in the current age, but it is weighed down with an almost unsurmountable number of negatives.

Allow me to present a speculative list of advantages these historical superheroes may have had in their favour, and then run a few comparisons.

But there are some significant challenges; beginning with the task of imagining yourself in the cultural landscape of the far east maybe a hundred years ago or even further back. This is a tough call for Westerners, as we have to peel away our own cultural understandings and inhabit the mindset of people half a world away, existing on cultural accretions that sit upon thousands of years of history, but please bear with me.

First of all, I want to present you with a puzzle that would be a useful starting place:

The possibility of rapid development.

If we take Japanese Old School (Koryu) Budo as an example, and we understand that there existed a well-established stratum of advancement; traditionally acknowledged by the presentation of sequence of certificates and eventually ending with a certification scroll that acknowledged ‘Full Transmission’, i.e. mastery of the system. That in itself could be considered a grand statement with a massive responsibility sitting on the shoulders of the recipient, the expectations are enormous, surely?

But, researchers reveal that these scrolls of ‘full transmission’ were sometimes offered to individuals with only a couple of decades of practice! I refer anyone who doubts this to Ellis Amdur’s book ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’. You have to ask yourself, how is that even possible?

In the recent ‘Shu Ha Ri’ lectures (mentioned in my blog post ‘Budo and Morality’) old time Aikidoka George Ledyard, when talking about the abilities of modern Aikido people (comparable to Ueshiba) poured cold water on an argument often brought forward in Aikido circles that if you train long enough, eventually you will ‘get it’ (something I have also heard said in Wado). In the interview Ledyard clearly called bullshit on that argument; to paraphrase; he said that they’ve had Aikido in the USA for over fifty years and still nobody can do ‘it’! I am going to be careful here as to what constitutes ‘it’. I’m not talking about fireballs of Chi emanating from fingertips; just effortless mastery and control is enough.

So, what is so very different? Let me put a few conjectural musings before you, in no particular order.

Proliferation.

In Japan in the 19th and early 20th century a huge number of mostly young men studied some form of martial art (it became part of the school system). These arts had evolved into a commodity with a price. Previously the martial arts were the domain of the warrior class, now, because of the abolition of this same class, out of work warriors found a niche living teaching anyone who would pay. (A good example of this is found in the detailed ledgers of lessons taught and fees charged by Ueshiba’s Daito Ryu teacher Takeda Sokaku.)

There was an awful lot of it about.

As a snapshot of the time; in his key formative years (pre Wado) the founder of Wado Ryu Karate-Do, Otsuka Sensei is said to have extensively sampled the huge proliferation of Dojo within a small area of Tokyo.

I think it is fair to assume that within this system there must have been a highly competitive filtration mechanism at work and it must have been very rough and tumble. To illustrate this point you have to wonder why it was that Otsuka Sensei would consider making a living out of treating predominantly martial arts related injuries? (At one point, Otsuka believed that this was an area worthy of supplying him with an income, but his teaching successes ultimately changed his trajectory).

Sanctioned Practice.

While it is apparent that the weapon training aspect of traditional Japanese martial arts struggled to survive (Naginata as an art was kept alive by the skin of its teeth mainly through the stubbornness of a few single-minded female protagonists) the empty-handed specialisms were adopted and subsumed by the powerhouse of the developing culture of what was to become Kodokan Judo. Judo, of course had a USP of being a ‘safe’ competitive format (see my blogpost on ‘Sanitisation’) and a builder of character, very much in line with progressive ideas developing within Japan at that time.

Even before that happened martial arts were considered part of the culture, and the Japanese have always been big on their culture, with a high regard for the arts and crafts and a special place for the artisans, and, it could be argued that the martial arts teachers were ‘artisans’. It may not be what an aspiring Japanese mother of the early Meiji Era might want for her son, but it still had the potential to provide respect and some form of status.

Lifestyle.

Looking at ancestors, either ours in the west or the equivalent in the far east, and, taking into account their social constraints, aspirations, outlook, mobility and world view, their bandwidth was pretty limited, compared to ours.

Theoretically our particular ‘bandwidth’ is huge, or at least it should be. For us, it’s not just the Internet, it’s education and all manner of loftier aspirations (being told what we should aspire towards) all supported by modern mechanisms, the structural framework of the society we live in and how we are kept secure by infrastructures that protect us from harm and ensure we are healthy.

Well, that’s how it’s supposed to work, but very recently things have become, to say the least, ‘challenging’, which in a way has highlighted some of the flaws in our current system.

Research has shown that this arguably ‘widened’ bandwidth is causing an actual shortening of our attention span, resulting in us leaping from one stimulus to another; one item of clickbait, and yet more irresistible reaffirmations on social media to boost our feeling of worth. Critics say this is actually dumbing us down and even restricting our brain power [2].

In the modern age the pressures of work leave less time to pursue other activities. In terms of martial art training in the west, anyone who trains twice a week is doing well and has probably established a good balance. Three times a week and people may say you are hardcore, any more than that and you’d probably be classed as an obsessive.

But this is so incredibly lightweight compared to someone like Shotokan Sensei Kanzawa Hirokazu who’s university training included multiple training sessions in one day! Or the Uchi-Deshi; the live-in students of Ueshiba Morihei, who not only had their daily training but were sometimes woken up in the middle of the night to be tossed around the Dojo by Ueshiba Sensei.

In historical Japan discipline and dedication were parts of the fabric of society, as were the virtues of hard graft and perfection of character through whatever it was you chose to dedicate your time, or even your life to.

Physicality.

The physicality of the early martial arts protagonists came out of a different lifestyle; even more so in rural areas, they were said to have ‘farmer’s bodies’. Ueshiba was a big believer in the physical benefits of tough labouring on the land and used it as personal training. There was definitely a culture of physical conditioning in the Edo period martial artists, photographs of Judo’s Mifune Sensei as a young man show a very impressive sculptured physique. Otsuka Sensei was said to have been keen on strengthening his grip, though his attitude to knuckle conditioning was somewhat ambiguous.

And then there is the issue of diet… A traditional old style Japanese diet has got so much going for it. It doesn’t mean that they were living in a health food utopia; for example; because of certain farming practices involving the use of human waste, internal parasites were surprisingly common. However, even with that, compared to our heavy use of sugars, processed foods and dairy products, they were by and large pretty healthy.

Longevity.

This has been a particular interest of mine. To take as an example; if you look at the lifespans of senior practitioners of the arts that use as a USP their health promoting benefits, e. g. Tai Chi with associated Chi Gung, it’s not particularly impressive. I have tried to dig into this but the statistics are a nightmare, particularly when it comes to average lifespans, mainly because of a lack of reliable information and infant mortality stats messing up the metrics.

But examined broadly, it doesn’t look great. Even with extreme outliers like the miraculous Li Ching Yuen. He was a Chinese herbalist and martial artist who it is claimed was born in 1677 and only died in 1933, making him 256 years old! Look into the supposed facts around his life and it begins to appear slightly suspicious.

On more than one occasion I have heard Japanese Wado teachers mention that practices found in other named karate systems are guaranteed to shorten your life, and a cursory look at the available evidence from those systems seem to support that idea, but even that doesn’t really tell you the full story. It has been said that some Japanese Sensei who come to the west seem to suffer from the negative effects of the western diet. Similar things are actually happening inside Japan; with the import of western food trends causing medical conditions to develop that used to be rare in Japan. Obviously, something that needs more research.

The lottery that is longevity can be skewed in your favour, if you lead a lifestyle devoid of extremes, striving for moderation in all things, then you have a better chance at living to a great age, but that of course is in competition with your genetic inheritance. Aforementioned Kanazawa Hirokazu pushed his body incredibly hard as a young man, potentially inflicting much early cellular damage to his system, yet still lived to be 88 years old. Mind you, Kanazawa adapted his training later in life to be kinder to his body, and he took up Tai Chi. But maybe his whole family line were predisposed to good health and longevity?

Speculative conclusion.

There is no definitive conclusion, only speculation.

Try as I might, I struggled to find any statistics that indicated martial arts participation in the UK, never mind about world-wide. Besides, what does that even mean? What even counts as a ‘martial art’? It would be really interesting to compare it to martial arts participation in Japan in the opening years of the 20th century.

I think it’s a fair guess to assume that the preponderance of martial arts in Japan in those early days would ensure some kind of higher waterline than in the modern world (well, at least I hope so). If we take the seemingly fast-track roadway to ‘complete mastery’ in 19th and early 20th century Japan as a truism, then that surely supports the argument – they weren’t giving Menkyo Kaiden (full transmission) away with Cornflake box tops and there had to be something going on! [3]

It’s true that they didn’t have the level of information at their fingertips in those days that we do today – but surely, it’s not the information, it’s what you do with it that counts.

In the modern era we are becoming further and further detached from the generation of masters who could actually ‘do it’, and if there are people out there who are on that level then they are side-lined by popularism. I cite as a possible example, Kuroda Tetsuzan (‘Who?’ I hear you say. It is ironic that his sparse, minimalistic Wikipedia entry speaks volumes, without saying very much at all.)

I suppose it all boils down to; who in the modern age is prepared to go beyond the mere hobbyist level and dedicate time and effort into an in-depth study of the martial art, supported of course by a Sensei who really does know their stuff?

Tim Shaw

[1] ‘Invincible Warrior’ John Stevens 1997 Shambhala Publications, pages 61 to 62. Other sources (Shioda’s biography) tell the story in more detail and mention that the marksmen were armed with pistols. At a guess, this incident was pre-war, possibly in the 1930’s. Shioda inevitably questioned Ueshiba, asking him how he did it? Ueshiba’s answer was as mysterious as the acts themselves, but he seemed to suggest that he was able to slow time down. Both times, one man was swept off his feet; the first time it was the man who Ueshiba said had initiated the first shot; the second time it was the officer who gave the command.

[2] Numerous modern commentators have railed against the ‘dumbing down’ that is happening. Google, John Taylor Gatto or Andrew Keen, but there are many other examples that perhaps don’t contain political bias.

[3] I am aware that there is a political dimension to the Menkyo Kaiden, certainly as it appears in the contemporary scene, which to me makes perfect sense.

Image: Author’s own collection.

Is Stoicism useful to martial artists?

Apparently, sales of books about Stoicism have rocketed during the pandemic. Why would there be a surge in interest about a school of ancient philosophy which is over 2000 years old?

Maybe, because one of the specific skill-sets associated with the Stoics is dealing with adversity; which is exactly why the Stoics may well have something to offer martial artists.

It is strange how the word ‘Stoic’ is used today. When you hear of anyone described as behaving stoically, it usually suggests that they are putting up with bad experiences or bad times in an uncomplaining way, or displaying zero emotion, or perhaps indifference to pain, grief (or even happiness). This is a little misleading and over-simplistic, and on its own, not particularly useful.

For anyone who has not heard of Stoicism before, a potted history may be necessary.

Stoicism is a school of philosophy originating in ancient Greece and enthusiastically embraced by key individuals in the later Roman Empire. It was established in the 3rd century BCE by Zeno of Citium in the city of Athens. Its main themes were the search for wisdom, virtue and human perfection.

After the Greeks it was eagerly embraced in ancient Rome, first by Seneca (4BCE – 65CE) a writer, politician and philosopher who was heavily embroiled in the politics associated with emperors Claudius and Nero and miraculously escaping two death sentences. Seneca’s ‘Letters from a Stoic’ is one of my go-to reads, an amazingly modern sounding set of conversations coming out of the long-distant past.

Stoicism was then picked up by Epictetus (50CE – 135CE) an educated Greek slave who lived in Rome, but was later exiled to Greece. He left no direct writings, but had one faithful disciple, Arrian, who dutifully wrote everything down.

Perhaps one of the most famous and accessible of the Stoics was the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (121CE – 180CE). Anyone who has seen the movie ‘Gladiator’ may remember that Marcus Aurelius appeared in the very early part of the movie played by Richard Harris, and although he actually did die of unknown causes whilst on a military campaign at the age of 58, it was unlikely it was at the hands of his son and successor Commodus, as the movie suggests, but why let the truth get in the way of a good story?

Marcus Aurelius was the last of the great and virtuous Roman emperors. Fortunately for us, he left behind a book, now titled, ‘Meditations’ and it is this book of Stoic wisdom that has been snapped up in the recent Covid year.

I had wondered if any modern martial artists had picked up on the Stoics? While there are a few online references, the tone very much suggested to me a misappropriation and over-simplified cherry picking; reminding me of how a particular disreputable 20th century fascist regime (who will not be mentioned) misappropriated and misunderstood the writings of Fredrich Nietzsche.

Yes, some of the writings of the Stoics seem to suggest a kind of toughness, but Stoicism is a bigger package, involving elements of compassion and love. This perceived ‘toughness’ emanates from the Stoics’ detailed dissection of human motivation and how we should respond to the trials of just living. What is really of value, matched against what is trivial and not worthy of our attention.

It is a very pragmatic, workable philosophy. I often wonder if boxer Mike Tyson may perhaps have been influenced by the Stoics when he said, “Everyone has a plan, ‘till they get punched in the mouth.” That might have come straight out of Marcus Aurelius’’ ‘Meditations’. He would have liked that.

There are many cross-overs between Stoicism and Buddhism, as well as Confucianism. It is a strange coincidence but scholars have pointed out that all of these great thinkers sprang up at almost exactly the same time in human history, but in places with no obvious geographical or cultural connections (Persia, India, China and Greco-Roman culture). Philosopher Karl Jaspers called it the ‘Axial Age’. The cross-overs are indeed uncanny, but I can’t help thinking that civilisations reached a particular pitch in their development which supplied the right nutrients for these philosophies to grow.

There is far too much on this theme for one blog post, but I will supply one example which is relevant to martial artists.

Stoicism is often referred to by modern behavioural psychotherapists, who tend to use a very close variation of this particular pattern of Stoic thinking.

(This comes from a recent podcast interview with psychotherapist Donald Robertson, information at the foot of this post.)

The ancient origin of this go back to a mischievous commentary engaged in by Socrates (considered to be one of the root thinkers of Stoicism) and dealing with the subject of managing adversity.

One day, Socrates said that he was incredibly disappointed with the way the heroes of Greek dramas coped with adverse situations, and that they’d nearly always got it wrong. His young companion asked him, ‘how so?’. Socrates then gave four pieces of advice on how to cope with bad situations.

- When bad stuff happens how do you know it won’t actually turn out for the better in the long run? To explain; maybe that job you didn’t get was not really for you and the next job is really the one that will launch you into a more positive future. Or, that girlfriend that you broke up with, actually did you a favour?

- If it already hurts, why voluntarily add on another layer of suffering by indulging in your own misery? (He’s not against regret or even grief, but if it goes on and on, then you are into another realm altogether, in the modern age it would probably described as clinical depression). Incidentally ‘venting’ is also of limited use; again, it can become habit forming.

- Although to you, in that moment, it is the end of the world; but in the grand scheme of things it may well be microscopic (depending on severity of course).

- Anger or freaking out may give you energy, but it actually inhibits clear rational thinking, which is actually the very thing you need to make yourself useful in a crisis. If it is your habit to fire up your adrenal glands to respond ‘positively’ then you’ve got it wrong. Over time, that particular habit will kill you. Some martial artists think that the fire of anger is useful, and train to artificially ‘switch it on’, – big mistake.

Of course, all of the above comes with a disclaimer; i.e. it depends on the situation and how extreme it is, not to put too fine a point on it, but, terminal is terminal, but even then, you still have choices. One of my heroes, Michel De Montaigne once said that the measure of a man is how he conducts himself when the ‘bucket is nearly empty’.

I recently re-read Viktor Frankl’s ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’. He chimes clearly with the Stoics and supports their idea that even in the worst of situations, you still have choices, you still have control. You can choose how you want to view the situation and you can choose how you want to react to it; even resignation is a choice.

Now put that into a Covid scenario. What is really interesting is how people choose to respond to Covid.

What would the Stoics have made of our Covid days?

Well, for a start, it wouldn’t have been anything outside of their experience. Socrates experienced a catastrophic plague at the age of 38 while serving as an infantryman. Likewise, Marcus Aurelius had to deal with the deadly Antonine plague which started in 165 CE and finally blew itself out in 180CE, with an estimated death toll of between five and ten million, located within a relatively restricted area, all of this at a time when they had none of the tools we have. With the Antonine plague (which was probably Smallpox) there was a dramatic shift in social structure, because, like Covid, it was indiscriminate, but inevitably was the scourge of the poorer classes. Having said that, Marcus Aurelius had to rapidly promote people from the lower orders, even freeing slaves, to ensure the infrastructure was able to operate. This was a perfect opportunity for a Stoic emperor to show what he was made of. Very much the Stoic ideal of changing what you can change, and not obsessing about what you can’t.

Yes, the Stoics taught resilience and a deep examination of human affairs, take these examples from Marcus Aurelius:

“Reject your sense of injury and the injury itself disappears”. (Obviously this not necessarily about physical injury.)

“Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life”.

And a particular favourite of mine and one to really ponder, “The art of living is more like wrestling than dancing”. And this from a man who knew about combat, both individual and large scale.

My view; there is much to learn from the Stoics.

Tim Shaw

Links:

Mo Gawdat podcast, talking to Donald Robertson about psychotherapy and Stoicism (says ‘Part 2’, but it’s really Part 1). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V8PH-DL5AI8

Marcus Aurelius ‘Meditations’ on Amazon.

Featured image: A marble bust of Marcus Aurelius at the Musée Saint-Raymond, Toulouse, France. By Pierre-Selim – Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18101954 (detail).

Budo and Morality.

Morality in Japanese Budo tends to be plagued with confusion and contradictions; not least of which is the concept of a warrior art used to promote peace. I am fairly sure that in this blogpost I am not going to be able untangle the knots; but perhaps I can add some new perspectives on this tricky issue.

I have to admit to wanting to write something on this theme for a long time but I have always swerved away from it; probably for the very same reason that many others seem to have avoided it.

I think that the main reason that people tend to duck discussing morality and Budo is the very same reason that people don’t feel comfortable discussing morality, full stop. Nobody is happy climbing on to anything that looks like a moral pedestal and have the spotlight shine upon them and risk looking like a hypocrite.

With me it is exactly the same, in that I don’t feel qualified or worthy enough to occupy that particular pulpit.

Introducing the subject of morality is a bit like the taboo around discussing politics and religion over the dinner table; two subjects guaranteed to spoil a good evening.

In the martial arts, I cannot think of any of the Sensei I have trained under who have been inclined to, or felt comfortable, climbing on to the moral soapbox. For the same reasons listed above.

Armenian mystic George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff (1866 – 1949) once said, “If you want to lose your Faith, make friends with a priest”. For me, that sums it up nicely.

However, I do believe that it is possible to tiptoe through that particular minefield and remain objective about morality in Budo.

In part, the reason for me writing this now is after recently viewing a series of on-line discussions with eminent Western traditional martial artists and, although their main theme was ‘Shu Ha Ri’, they often strayed into the thorny area of morality within Budo and the development of ‘moral character’. If you have six hours spare you can follow the link below.

It is said that in traditional Japanese Budo the Morality rules are literally woven into the fabric. I use as an example the traditional divided skirt, the Hakama. This garment has seven pleats, with each one said to represent the ’Virtues’ sought within Budo, these are the guiding moral principles. Some people say there are seven, others say five, but for convenience I will stick with the seven model. These seven are:

- Yuki – Courage.

- Jin – Humanity.

- Gi – Justice or Righteousness.

- Rei – Etiquette or Courtesy.

- Makoto – Sincerity or Honesty.

- Chugi – Loyalty.

- Meiyo – Honour.

These are described as ‘Virtues’ rather than as components of a moral code. The word Virtue is a better fit because in the west the concept of being moral tends to lead you in a slightly different direction than the Japanese model. Being ‘moral’ in the West has too much baggage, a hint of the fluffy bunny feeling about it. Either that or it is associated with po-faced condemnatory Victorianism.

Rather, the suggestion here is a person of ‘Virtue’ or with ‘Virtues’, or, alternatively, ‘Qualities’, but these must be positive qualities.

But there are a number of things within the traditional list of Budo virtues that don’t translate well. There are two main reasons for this.

Firstly, because the translations, like the Kanji, are multifaceted and have to fit into a Japanese cultural and linguistic framework.

Secondly; these martial arts virtues are the product of an Edo Period mindset, or even further back. Clearly the social structures and the mental landscapes of warriors in that particular place and at that particular time are far removed from the way we live today.

Even the translation of what would seem a fairly self-explanatory concept offers up some questions.

I will address one example, not directly mentioned in the above list, but certainly connected to it. (and this is a person reflection):

From my experience, nobody under fifty years of age ever seems to use the word ‘honour’ anymore, let alone adhere deliberately to the concept. ‘honour’ only sees the light of day in the most negative of circumstances, as an example, the concept of ‘honour killings’, how did that happen?

In much the same way as, in today’s social interactions, no man is ever referred to as being a ‘gentleman’. Similarly, across the genders. I cite as an example this observation: For many years I worked as a teacher in a Catholic girls school, and it always amused me when I saw young girls being chided by female teachers for ‘un-ladylike behaviour’, what does that even mean today? I suppose you could talk about the same behaviour as being ‘undignified’, but even that word has worn a little thin these days. (I refer you to the justifications given by St. Miley of Cyrus for the contentious ‘Wrecking Ball’ video, of which I have only heard about, of course.)

I am old enough to remember when two ‘gentlemen’ shook hands over a deal it was this symbolic act and their ‘honour’ that sealed it. It all seems to have disappeared from the world of commerce and is only seen on the sports field.

Another example from the modern lexicon is the word ‘respect’, which seems to have been warped and weaponised and is permissible to function as a one-way street. This is particularly noticeable in urban slang.

But to return to the above listed Japanese Virtues.

‘Jin’ as ‘Humanity, also has a very nuanced meaning in Japan.

Yes, it does refer to the ideals of a care and consideration of other humans beyond yourself, but also ‘Jin’ is a model of humanity perfected; we all aspire to be ‘Jin’, or at least we should be. From my observation the Japanese concept of humanity is similar to Nietzsche’s model in ‘Thus Spake Zarathustra’; of Man suspended on a tightrope caught between his animalistic nature and his God-like Divine potential. ‘Jin’ is that Divine Potential realised. It is Man perfectly positioned in the universe as the sole conduit between Heaven (the universe) and Earth. It is the triad of ‘Ten, Chi, Jin’.

For convenience sake, Morals, Virtues and Values can all be tied together into one bundle.

Regarding Values; there has been a relatively recent push towards looking for values shared across cultures; values for the whole of humanity. As we work towards an idealised global community this was considered a goal worth striving for. But it’s not as easy as it looks.

The dominance of Judeo-Christian culture and ideals over the last 1000 years has pretty much set the standards for what we understand as moral behaviour (and values) and has achieved a world-wide monopoly on what is acceptable and desirable. But we have to remember that Judeo-Christian culture is the new boy on the block.

Other cultures had been hammering out their moral codes for thousands of years before Judeo-Christian models appeared on the scene, and it is quite often at variance to what we would now deem acceptable. As an example; activities condoned in ancient Greece and Rome would cause shrieks of horror in modern Western society.

Further east, Chinese culture was blossoming when we in Europe were hitting each other over the head with sticks. Chuang Tzu in 200 BCE was wrestling with advanced philosophical problems of human consciousness (See, ‘The Butterfly Dream’) and the Han Chinese at the same period had advanced tax systems, hydraulics and machines with belt drives; while at the same time in Britain we were embroiled in Iron Age tribal brutality and cattle stealing, and then along came Christianity and everything was alright! (Sarcasm alert).

Morality still has an important role to play in contemporary martial arts, even though the world has moved on and the fabric of society has changed and continues to do so at a terrifying rate. The nature of martial arts study in the modern age inevitably involves people and wherever human interaction occurs we are better working towards common goals for the improvement of society. We are living examples of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts.

How about a campaign to restore the word ‘Honour’ and claim back the word ‘Respect’?

Respect to you all.

Tim Shaw

Featured image: Author’s own collection.

Smoke and Mirrors.

It is said that magic ceases to be magic once it is explained; although the late fantasy author Terry Pratchett contradicted this with, “It doesn’t stop being magic just because you know how it works.” I think I know what he means.

At an objective and scientific level this is the difference between the ‘natural’ and the ‘supernatural’.

Martial art skills often appear to be supernatural, where the masters are in possession of abilities that seem to be out of reach for the average person in the street; this is part of the mystique, a million fantasies have been built on this idea.

However, there are times when refined and developed technique seems to confound the mind and contradict the physical world, whether it’s Bruce Lee’s one-inch punch or Aikido’s ‘unbendable arm’ (See my previous blog post ‘On Things ‘Chi’ and ‘Ki’’).

Without allowing myself to be diverted, there has been some quiet rumblings about the more subtle aspects of Wado technique and, for the cognoscenti, a suggestion perhaps that there is more going on under the hood than the recent Gendai Budo incarnations seem to imply. And, as such, I want to shine a light into an obscure oddity that may have a peripheral connection to aspects of Wado technique (as I understand them), via a tortuous route – please bear with me.

I have been sitting on this for quite some time and thought I would share it with you*. It may be nothing, it may be something. It may even be an excellent illustration of the human capacity for boundless curiosity, and what can come out of it. You can make your own mind up.

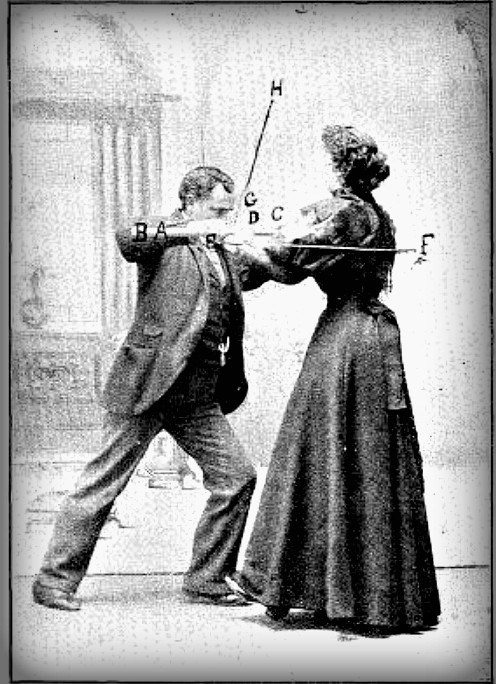

Lulu Hurst was to all intents and purposes, outwardly an unremarkable young woman, born in Polk County, Georgia USA in 1869, daughter of a Baptist preacher, but overnight, as a teenager, she became a high earning freakish phenomenon who confounded the paying public with her jaw-dropping feats.

Dubbed ‘The Georgia Wonder’ she performed impossible acts of human strength. When asked where her skills came from the slightly built Lulu said they came as a result of her being caught in an electric storm, she was a supernatural human miracle. Even the great Harry Houdini was initially puzzled as to where this phenomenal strength came from.

Lulu was able to take the weight and strength of a number of men, often through a chair or a staff, and with only a light touch displace the resisting men. She was often completely immovable, no matter how much pressure was applied. When I first heard this story it started ring bells with me; where had I come across similar phenomena?

And then I recalled stories, anecdotes of comparable abilities being demonstrated by the founder of Aikido Ueshiba Morihei. He would hold out a Jo and ask his students to try and move it – sounds easy, but try as they might they couldn’t shift it. No explanations were given, or if they were, they were shrouded in mystical obfuscation.

Over time more of these unexplainable phenomena appeared on my radar – even with the possibility of conscious or unconscious compliance it seemed that there was something there.

But Lulu retired after only two years; she’d made her money and at the tender age of sixteen she ran off and married her manager.

Years later Lulu admitted what she had really been up to; which in my mind was no less of a wonder, but certainly there was no magical ‘electrical storm’, something much more ‘grounded’ was at work.

She finally confessed it all in her autobiography. It wasn’t the product of some great revelation; she just came across it by accident.

Her first realisation was when she held a billiard cue horizontally in front of her at chest height and invited someone to push with all their might, to try and knock her over; they couldn’t! She developed it to such a degree that a whole bunch of hefty guys could push on it and STILL couldn’t dislodge her! Then she really got into showmanship, and performed the same trick standing on one leg!

From this beginning she developed a whole array of ‘tests of strength’. What is surprising though is that initially even she didn’t know how it was done.

She was smart enough to deny the supernatural and set about studying what was really going on. The level to which she was puzzled by her own ability is illustrated by the fact that her manager/husband had asked her repeatedly to teach him how to do it, but she couldn’t, because she didn’t know herself.

Finally, she did figure it out, through studying mechanics and physics. To keep it really simple the first trick, with the billiard cue, came out of her ability to read and direct the energy of the resistance and send it into… nothing, the men were not engaging with her at all.

Houdini spotted it, but it took him a while. As the master of illusion and physical manipulation himself, it was only a matter of time.

She became more adept at these forms of manipulation, and added all of this to her act.

Does this make Lulu Hurst any less remarkable? No, not in the least.

You can read her autobiography for yourself, but be warned, it’s a slog of a read, couched in the flowery language of the time. It is called, predictably and unimaginatively; ‘Lulu Hurst (The Georgia Wonder) Writes Her Autobiography’ 1897.

To reiterate; human curiosity and the ability to explore and expand beyond the realms of what is normally accepted really does know no bounds.

Tim Shaw

*The first time I ran this idea by anyone was in communication with a now disgraced famous UK karate historian back in the 1990’s. He seemed to think I was on to something.

Photo credits:

Illustration of Lulu Hurst chair act, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 26th, 1884. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/file/11051

Black and white photographs of Lulu Hurst: credit, ‘Lulu Hurst (The Georgia Wonder) Writes Her Autobiography’ 1897. Free of restrictions on copyright.

Bad Apples.

Book Review: ‘Humankind: A Hopeful History’.

I have to admit to spending an awful long time mulling over what it is with the human race that makes us such a toxic species, with our proclivity towards violence and seemingly unplumbed depths of out and out badness.

I remember being convinced that everyone one of us has the capacity for unspeakable savagery and that the veneer of civilisation is so very thin. Now my opinion has changed considerably; all down to one book, ‘Humankind: A Hopeful History’ by Dutch historian Rutger Bregman.

I had read Bregman’s previous book ‘Utopia For Realists: And How We Can Get There’ and was impressed. Bregman seems to be one of those people who are prepared to not accept everything at face value AND to think outside the box. In addition to that, he will call foul if he sees it, as he did with Tucker Carlson of Fox News, (Google it!). And shaming the Davos delegates; “Almost no one raises the real issue of tax avoidance…and of the rich not paying their fair share” . [Link]

Bregman is great at presenting the evidence and supplying concrete examples of how things have been done differently. But in this latest book he goes further.

Humans are hard-wired to see the worst in people and societies have further hard-wired themselves to expect the worst of the whole of humanity. Bregman explains how this has all been of use to us and how it’s been cynically exploited; from; ‘original sin’ to group culpability and the fear of the outsider. But the evidence suggests that if push came to shove we are also hard-wired towards compassion and amazing acts of cooperation and generosity. We are pretty awesome!

In his book Bregman deconstructs the premise of William Golding’s novel, ‘Lord of the Flies’, and proves that in a real situation the complete opposite would happen (and it did, in 1965, when a group of schoolboys were stranded on an island for fifteen months). Bregman says that our ‘superpower is cooperation’. He also examined the Stanford Prison Experiment of 1971 and called it out as baloney, the same with the Stanley Milgram ‘Electric Shock’ experiment of 1961. It looks to me like not only does a whole bunch of English Lit. commentaries on ‘Lord of the Flies’ have to be re-written but also lots of psychology text books!

We’re not completely off the hook though; the concept of ‘empathy’ takes a bashing, and additional bad news is that we can’t unweave the societies we constructed; but, perhaps, by reading Bregman’s book we can at least understand how our motivations work.

A chapter titled; ‘Homo Ludens’ (Man at play) really cheered me up, as it chimed with things that occurred to me gradually over years of working with children (the open-endedness of ‘play’ I mentioned in a previous blog post, here.)

It’s not that difficult to connect Bregman’s optimism to concepts found within Japanese Budo. Recently re-reading Otsuka Hironori’s book, particularly the section, ‘Analects of the Instructor’ it was obvious to me that master Otsuka’s underpinning philosophy was founded upon peace and the bringing of peoples together. In fact, if you deconstruct the Kanji for ‘Wa’, normally understood as ‘harmony’, and take it back to its basic pictographic level you would struggle to find a better example to sum up the spirit of the ‘super power’ of cooperation, with its allusion to the collaborative and civilising mechanisms found in agrarian societies. In Dave Lowry’s book, ‘Sword and Brush: The Spirit of the Martial Arts’, there is a description of ‘Wa’ from Japanese tea ceremony devotees, Harmony (‘Wa’) is, “the capacity to get along with others, to sublimate the self for a greater cohesion within the larger social nexus”. The image for ‘Wa’ is of a pliant healthy rice sprout positioned next to the symbol for a mouth; either representing ‘feeding’ or just civil discourse and communicating, or a combination of both.

To literally restore your faith in humanity, I would thoroughly recommend that you pick up this book and reflect on the wider implications of Bregman’s observations. It could not be more apt, particularly in the times we are living and with the vague possibility of a re-think of our values and systems in a post-Covid world.

Tim Shaw

The Wisdom of the Architects.

What architects can tell us about kata.

I think there is much to be gained from approaching a well-known subject from a completely different angle. Kata has been the backbone of everything we do within Wado karate; it’s the text book we all return to, particularly when we are working to get to the heart of our martial system. It is everything; a receptacle, a framework, a compressed and concentrated format for us to explore, move through, or dwell upon; all qualities you may find in a superior piece of architecture. And, like amazing architecture, it may be inspired by pure Principle, but it is still a man-made construction, carefully designed and thought-through and meant to last.

Both kata and architecture have form and function; though, for many people, the initial focus for both kata and architecture tends to be on the form; function has a tendency to be a secondary consideration. But really, both of these aspects should be given equal status, and there are other qualities, harder to pin down, also of major importance.

Many years ago, I was in conversation with an architecture student. I’d asked him what were considered to be the most important factors when designing a building? He replied with one word, “Flow”. This was the ability for people to move in, out and through the building.

It certainly wasn’t the answer I was expecting, but it changed my appreciation and understanding of every great building I have since visited.

Perhaps one of the best examples of this is to be found in the 2014 National Geographic ‘Bird’s Nest Stadium vs The Colosseum’ documentary ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVfQdjpXa4k ) where computer simulation compares the efficiency of the evacuation process of these two great buildings, separated by nearly 2000 years. Spoiler alert – It seems that the Roman architects did rather well and certainly understood ‘flow’.

A long time back, when I was a student of design, I came across the work of the Swiss-French designer and architect known as Le Corbusier (1887 – 1965). Initially I was drawn towards his ‘Modulor’, this was a calculation model that took into consideration the proportions of the human body to work out optimum living space; which again could chime comfortably with considerations of the design of kata; but, for the sake of this comparison I find another of Le Corbusier’s insights particularly pertinent, his description of a house being “a machine for living” (1927 manifesto); it provides us with a potential paradigm shift when looking at kata.

Try this thought; ‘Wado kata is a machine for human movement’? Or, ‘Wado kata is a machine for fighting’? Of course, depending on your predilection, you could tag on any number of concepts that would work for you.

But what of the spaces, the gaps, the shifts between ‘A’ and ‘B’?

Here I could dip into a much older source; Lao Tzu ‘Tao Te Ching’ (4th century BCE).

“A jar is formed from clay,

but its usefulness lies in the empty centre.

A room is made from four walls,

but its usefulness lies in the space between.”

Le Corbusier would have found that quote resonated with his own thoughts.

Certainly, the use of open or ‘empty’ spaces in Japanese Zen-inspired art is a highly refined utilisation of not shying away from the void.

The same could be said about another architect; Frank Lloyd Wright (1867 – 1959). It is said that he was able to create buildings which upon entering filled people with an ineffable sense of awe; but not one based on pure scale. Architecture students found it difficult to pin down, until they shifted their focus from walls, ceilings, supports etc. and looked at pure space.

Wright instinctively knew how to manipulate openness, airiness and the effects these have on the deeper levels of human consciousness. I experienced this myself in a museum reconstruction of a Frank Lloyd Wright interior in New York. Just being in this room made me want to stay, to breathe it in, I was overcome with a feeling of comfort, tranquillity and many other things besides. I was being manipulated by the architect!

Would it be too far fetched to describe the hardware, the walls, ceilings, floors as Yang; while the spaces in between are the Yin?

And what of the gaps in the kata? The spaces between the structure; the pauses in between, the apparent quiescence of the ‘Yoi’ position? The punctuations, the declarations of intent found through ‘Kiai’ (with sound or without)?

Katas become our cathedrals. Each kata is an edifice, a bringing together of ideas and resources to create a focal point. The kata also give us a sense of occasion, a place for ritual and reverence, including unashamed symbolism (the overt salutations found in kata like Bassai, Kushanku etc.)

With all the great cathedrals and temples, people bring their own psychological and physiological baggage with them, and may well attempt to refine or polish their spirit within that environment, within that framework.

It might be lazy categorisation, but I see those who look at buildings and see walls, floors and ceilings, and those who see kata as punches, blocks, kicks and the ‘making of shapes’, as ‘materialists’.

But sometimes materialists need to be put back in their box, and shouldn’t be allowed to have it their own way, to hijack the debate on kata. Yes, there is a material form to kata, for isn’t ‘form’ the literal translation of ‘kata’ – and here we could get into Otsuka Sensei’s ‘kata’ v ‘igata’ debate, but I will skip that for now.

Kata needs to be a living thing, just as buildings need to come alive through their functions. The original architects of the great buildings didn’t wholly impose their will upon the people who used them, but instead, through the spaces, galleries and chambers they created they fuelled the imagination of generations to come, who were then able to reach beyond themselves and engage with the greater project of ‘being’.

Tim Shaw

“Why does every lesson feel like ‘day one’?”

Reflections on how karate students sometimes struggle to grasp the idea that they are progressing and improving.

When you are sat on an aeroplane; comfy and strapped into your seat; alongside lots of other people who are also passively settled in their own seats; have you ever thought about the wonderful contradiction you are experiencing? There you all are, row upon row of people, not going anywhere. But just glance at the flight progress animation in the little screen in front of you (long haul of course) and think of the vastness of the planet and the distance your plane has travelled in the last hour and then tell yourself you are not going anywhere. Of course, it’s all so ridiculous and obvious and easily dismissible.

I know everything is relative; as Heraclitus said, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man”. So why do karate students sometimes get the feeling that every lesson is like day one? Why is it so difficult sometimes to observe your own progress?

Of course, it is entirely possible that no progress has been made; what is it they say, “If you always do what you always do, you’ll always get what you always get”. But, as a quote, it’s a bit of a blunt instrument. It might just be that progress is so slow that it is barely perceptible, like the hands of a clock.

There was a Dojo I used to visit quite regularly in the early 1990’s which had the same membership for many years; but when opportunities came to advance came along, be it through gradings or something else, the students shrank away. Yet week after week they came back and did the same session. Oh, they would work hard and they loved what they were doing but they just stayed the same, they never improved. Whether they thought that the penny would eventually drop, or that maybe they learned by osmosis, or whether they were just keeping fit, I never knew, they just never improved.