Ideas

Martial Arts Movies.

I have avoided this one so far, but was recently tempted by a friend issuing me the challenge.

I was inclined to just supply a list of personal favourites, but I think there is more to say.

I have to start by mentioning that martial art movies, TV series, Box Sets have always been a massive let down for me. I think that why they are so much of a disappointment is because I genuinely believe that there are some amazing untold stories and narratives that have never been explored.

But, never mind the stories, what about the action? Is it actually possible to portray martial arts as it really is? Maybe with new technology and ever more adventurous camera angles it can be done, the problem is, could we wean ourselves off the overblown, exaggerated action? There is some evidence that the silly extremes have become a little passé, nobody has the appetite any more for the ‘Wire-Fu’ antics of the type seen in ‘Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon’, I think the public have called it out as too much of a stretch on their credulity.

What the public seem to want now is the crude, rough and violent approach of John Wick or Daniel Craig’s Bond in his opening salvo in ‘Casino Royale’ (that washroom scene, all those broken tiles and ceramics!) I am convinced that the fight choreographers took a huge cue from Jason Bourne, and later was to come ‘Atomic Blonde’ (Charlize Theron) with its famous ten-minute single take fight scene, that is about as rough as it can get.

By dialling it back could we perhaps reach something with more integrity without losing the drama?

I assume most people reading this have a Wado background; Wado is about as anti-drama as you could get, despite the efforts of some senior Sensei to play to the gallery; all for very good reasons I’m sure. I once asked a very senior Japanese Wado Sensei about one of the Tanto Dori he would perform as part of his regular demonstration techniques; he said he performed it in an exaggerated manner, not a ’true’ manner, so the people in the cheap seats could see what was going on. Well, in the movies there are no ‘cheap seats’, we are all up-close and personal, in fact some cinematography of fight scenes has even gone so far as to CGI rib-breaking, organ-busting x-ray images, to give the audience the closest of closest visualisation (seen in ‘Romeo must Die’ and other movies).

Audiences are much more sophisticated now. People used to think that the concentration span of the average audience member was continually shrinking, but really the trend seems to be going the opposite way; two examples; boxsets tell a story over ten episodes of an hour each and people enjoy the full depth of character and interwoven plot lines. Also, podcasts, like Joe Rogan’s, are sometimes three hours in length – they might not be consumed in one sitting but there is an appetite for it. This is where the recent Cobra Kai for me got it wrong. Clearly, they traded off the 80’s nostalgia thing (everybody is doing that now) but the plot line was basically the same that you could tell in a two hour movie, and then repeated; compare that with something like Breaking Bad and there’s a world of difference (BB is like Homer’s Iliad). Cobra Kai was like watching a loop of the typical High School teen movie – Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy wins girl back, a bit of revenge etc. etc.… and repeat.

Who needs a plot anyway?

Two words… ‘The Raid’, for me a totally enjoyable kick-ass movie with the most minimal of plot. (okay so ‘The Raid’ and the ‘Judge Dredd’ movie were filmed almost at the same time, but who cares, both of them did a good job of working the same story).

There’s more than one type of Martial Arts movie.

Let me try to construct some categories here, with some suggestions:

- Kung Fu movies, going way back. Initially for the Chinese audience and then westerners started to find them cool, with a big spike during the Kung Fu boom.

- Art House style ‘wire-fu’ movies, like ‘House of Flying Daggers’ (interestingly ‘The Matrix’ is classified as ‘wire-fu’ because of its similar use of wires, pulleys and harnesses).

- Samurai movies. Similar to the above but, for my mind, given a major Art House boost by Kurosawa. Do yourself a favour and binge on the Kurosawa classics. And his career did not end with the beginning of colour film. Later favourites, spectacular, amazing use of colour; ‘Kagemusha’ (Shadow Warrior) 1980 and ‘Ran’, King Lear in armour 1985.

- Western-based martial arts movies – It is very easy for some good movies to slip under the radar here; example ‘Red Belt’ 2008, great cast, great director David Mamet, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor, a modern and relevant movie.

- Movies where clearly the stars have martial arts skills; Recent James Bond movies, John Wick, Jason Bourne etc. More like thrillers with a lot of choreographed moves. But for me, a special shout-out for the ‘Blade’ trilogy. ‘Blade 2’ particularly, martial arts with vampires a terrific director, Guillermo del Toro, what’s not to like?

Martial Arts Novels.

This will be very short because there is absolutely nothing I can recommend, despite my best efforts. There are numerous thrillers with a loose martial arts connection – usually about ‘assassins’ which don’t really float my boat. Decades ago, I read the Eric Van Lustbader stuff and found it really lightweight.

I recently read a novel that initially got me excited, ‘The Gift of Rain’ by Tan Twang Eng, there was an element about a Japanese Aikido master, but it was never really fleshed out and the story just tried to do too much. I stayed with it till the end, but it could have been so much better.

After writing all of this I realise that I am perhaps too demanding an audience. It’s like commenting on music; so easy to talk about what you don’t like, almost impossible to persuade someone of the merits of what you do like.

Tim Shaw

Follow my developing Substack project; a weekly blogpost/newsletter published every Tuesday, with writings on martial arts, Wado karate and all things related. To support this project, please subscribe; that way I can promote all things ‘Wado’ and everything in-between. You can find this at Substack

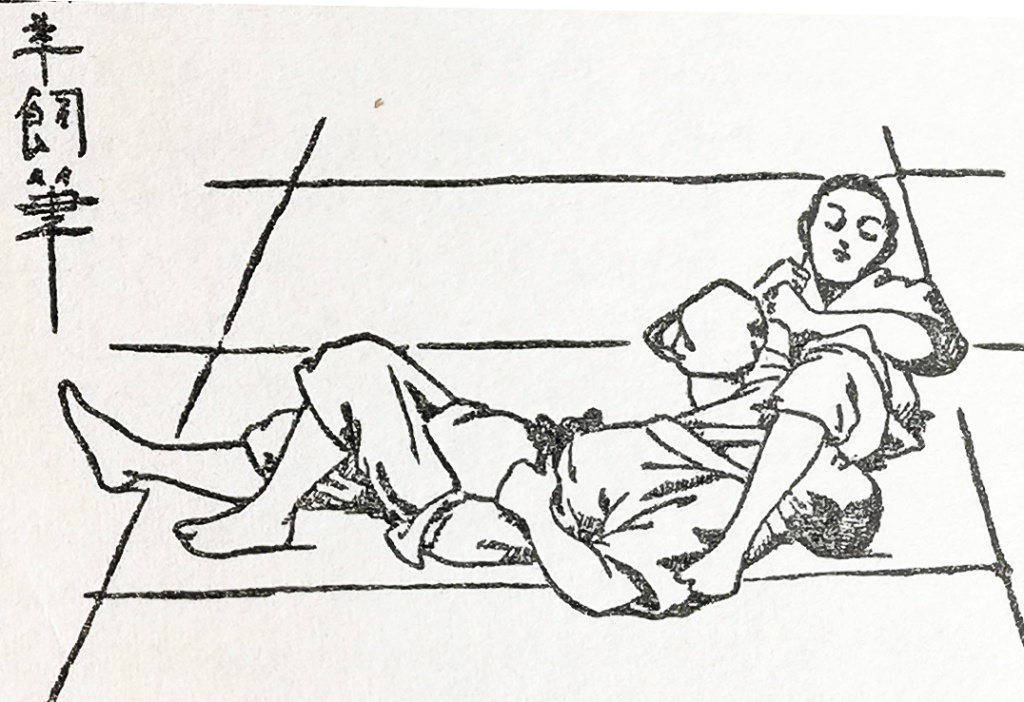

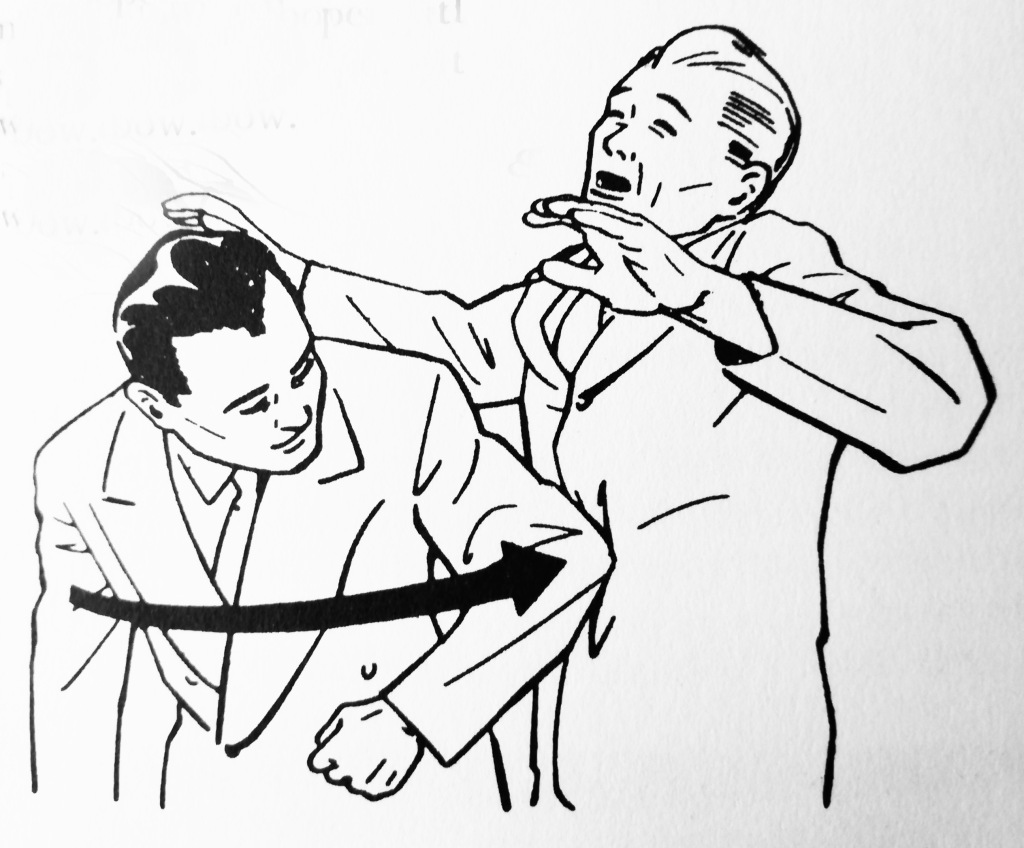

Image credit: https://www.furiouscinema.com/ Still from ‘Invincible Armor’ 1977. Director, Dir: See Yuen Ng.

Substack Project.

I have been thinking about this for a very long time, looking for a platform that works as an extension to all the effort put into this blog, and after much research it seemed that the best fit was Substack.

What is Substack?

Substack refers to itself as a subscription ‘newsletter’ but really, it’s a blogging platform which has a built-in email function that allows subscribers to opt for the cost-free content or the paid content (the latter is for chunkier items that are only available behind a paywall).

Some very big celebrity artists, writers and political thinkers are using the Substack platform; to name a few; Salman Rushdie, Garrison Keillor, Patti Smith, Michael Moore (Bowling for Columbine), Chuck Palahniuk (Fight Club), Dominic Cummings, etc.

Why?

This started a long time ago when I was researching and writing articles for the earlier incarnation of my website. I would spend months researching and writing articles like ‘The Naihanchi Enigma’ and ‘Wado and Jujutsu’, publish them on the site and later find that they’d been ripped off without permission or acknowledgement. I initially staged a fight back, but realised that everything on the Internet is up for grabs, it was futile. But the worst of it was that it put me off ever venturing into longer meatier writing projects again. However, I just couldn’t resist writing and I really relished the research and the contacts I had made along the way [1].

I have so much stuff in my back pocket.

As an example; years ago, I penned longer studies on themes like ‘Martial Arts and Meditation’, also a personal angle on what I’d observed in the development of Wado in the UK over the last 40 years (which was big enough to warrant a book on its own). During lockdown I typed many thousands of words on recollections of my own training experiences (snippets of which I have published on here as a taster). In addition, the ‘Naihanchi’ piece is in serious need of an update, as my understanding of both Naihanchi and Seishan has changed considerably. Similar with the ‘Wado and Jujutsu’ piece, which is way out of date, despite my recent efforts – my thoughts have changed yet again!

What’s the Plan?

First of all, I am concentrating on the free subscription material – shorter pieces not dissimilar in length and content from the posts on this platform. I will not be duplicating the posts on here – it would be so easy to just link the two together but the Substack posts will be more technical and theoretical in nature. My thinking is that by running the two separately this will expand the audience. It might be that the two blog platforms will take on different identities through themes etc.

I am hopeful for this new venture, but equally, if it doesn’t work out at least it was worth a go.

Link to the Substack site: https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

Tim Shaw

[1] I had useful information from such renowned martial artists and researchers like Meik Skoss, William Bodiford, Toby Threadgill and others, all of whom put me straight and extended my understanding.

I am grateful to Steve Thain for the suggestion of the name for the Substack project. I agonised over that for a very long time but ‘Journeyman’ chimed with me, as it relates to the ideas found in the medieval guild system. A Journeyman is a middle rank artisan, no longer an apprentice and some considerable way from being a master craftsman.

Humbled Daily.

Before I launch into this latest blog theme, just a quick word about a new development.

I wanted to extend this writing project into something bigger and so have set up on Substack, a subscription service which is really taking off. I will write a following blog post to outline my plans, but basically it is already up and running. Please support this new project. It can be found at: https://budojourneyman.substack.com/

On with the theme…

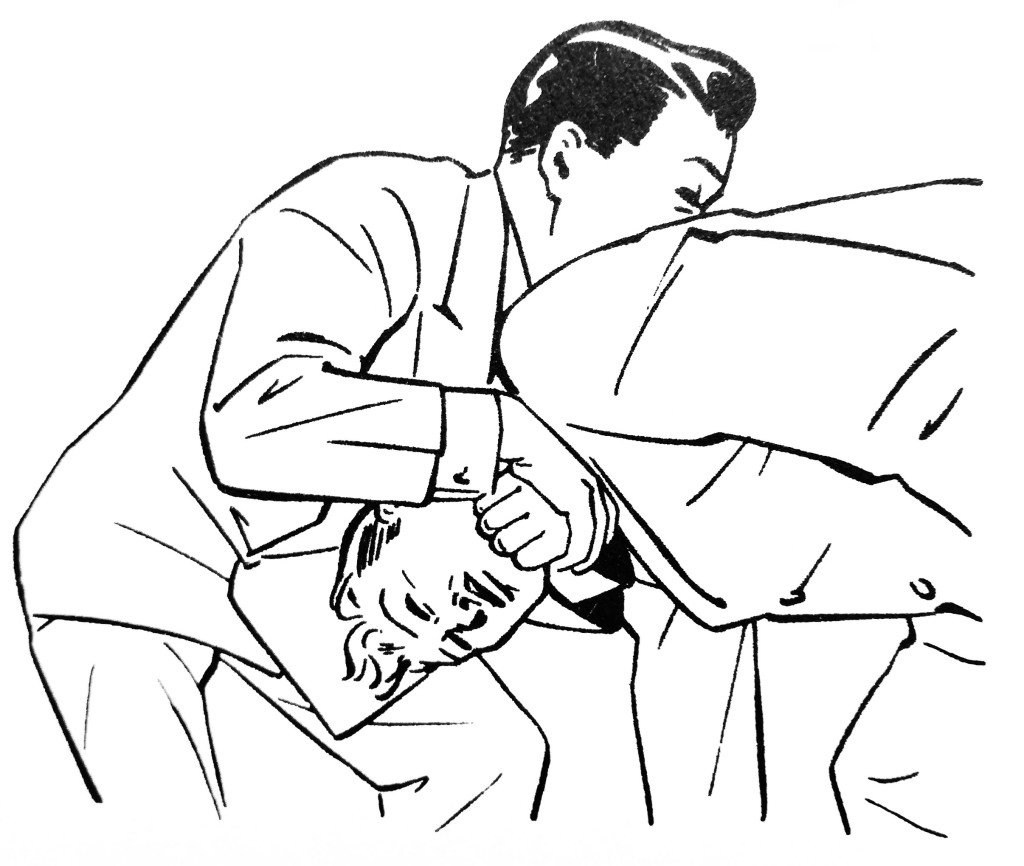

In a recent interview with movement guru Ido Portal he mentioned that grapplers and wrestlers get humbled daily, and it was a healthy thing. They roll on the mat with people of different abilities and frequently experience the challenges that such opportunities present. Often, they fail in their intentions; frequently someone else’s intentions win over theirs and they experience failure. In fact, an intense session may well involve a rolling series of mini-victories and mini-defeats. These are all valuable growth experiences. [1]

Portal says that this seldom happens in traditional martial arts, and he’s right. While not being entirely absent, it certainly doesn’t happen to that intensity.

In traditional martial arts very often the training scenario is so tightly directed that there is little space for this type of training; or, in some cases ‘loss’ is too high a price to pay that it is actually demonised, or only seen for its negative attributes.

What are the real obstacles for us as traditional martial artists to engage in parallel ‘humbling’ interchanges? Here is a list of the potential problems:

- Attitude, this might be related to ego, rank, status etc. I find it ironic that ‘humility’ in Budo is seen as a positive attribute, yet the aforementioned attitude problems are allowed space in the Dojo.

- Avoidance. We know the phrase ‘risk averse’, if you don’t willingly embrace challenge it’s going to be very difficult to improve. [2]

- The constrictions of the training format. We know that our training in traditional martial arts is limited by having to fit so much into a limited time; our priority has to be the syllabus as this is the framework upon which everything depends. How to overcome these limitations often falls on the creativity of the Sensei. Some are good at this, others not so.

- The absence of ‘Play’. Often derided, but, if we think about it, some of our most powerful learning experiences have come to us through play – we only have to think of the physical challenges of our childhood.

And what about competition and sport?

The demonisation of ‘loss’ is perhaps amplified when martial arts become sports. Although, today there is a trend where everybody has to be a winner, it’s an illogical formula. I will counter this with the pro-hierarchy viewpoint. If there is no ladder-like hierarchy to climb then there is no value system. When everything becomes the same worth there’s nothing to aspire to, no striving, no reaching, the whole enterprise becomes meaningless.

In a karate competition the winner’s position becomes of value because of everyone who pitched in and competed on that day. The winner should feel genuine gratitude towards all of those who competed against him or her, it was their efforts that elevated the champion to that top position. And, although all of those people don’t get the trophy or the accolades, they gain so much in the experience of just competing. This is the true ‘everybody is a winner’ approach.

In a healthy Dojo environment instructors are beholden to devise ever more creative ways of training to allow students to experience lots of free-flowing exchanges, where mistakes are seen as learning experiences. A while back, I shamelessly stole a phrase from an ex-training buddy who was from another system. He called this stuff ‘flight time’, as in, how trainee pilots clock up their hours of developing experience. If you get the balance right nothing is wasted in well designed ‘flight time’ in the Dojo. Over the last ten years or so I have been working on different methods of creating condensed ‘flight time’ experiences. When it’s going well there are continually unfolding successes and failures, and the best part of it is that during training everybody gets it wrong sometimes and therefore has to learn to savour the taste of Humble Pie.

Bon Appetit.

Tim Shaw

[1] I have heard similar things from the early days of Kodokan Judo, hours and hours of rolling and scrambling with opponent after opponent.

[2] ‘Invest in loss’ is a phrase often heard among Tai Chi people. It describes the lessons learned from failure. The late Reg Kear told a story about his experiences with the first grandmaster of Wado Ryu, who said something similar to, ‘when thrown to the floor, pick up change’ and then, with a smile, mimed biting into a coin.

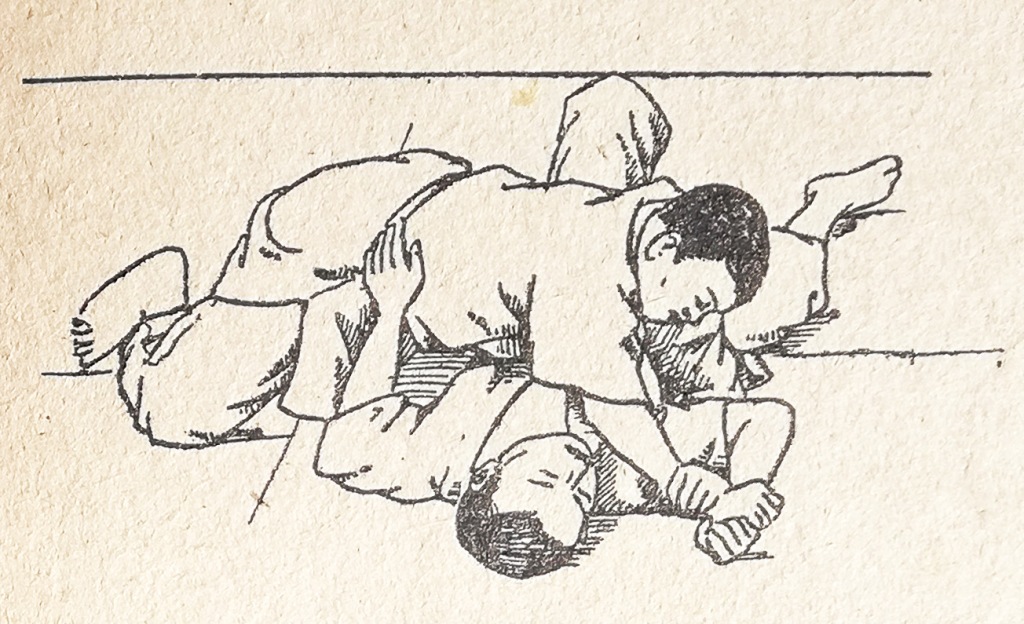

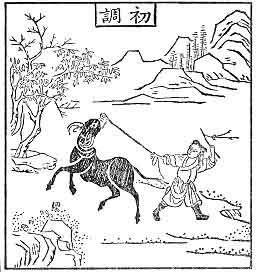

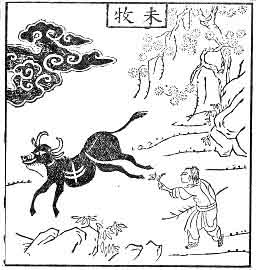

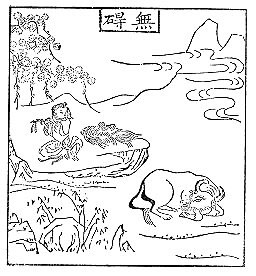

Featured images from ‘The Manual of Judo’, E. J. Harrison 1952.

Books for martial artists. Part 2. East meets West, and West meets itself.

In this second part I want to dip a toe into the way ideas originating in the far eastern martial arts migrated to the west and then morphed into something else.

Also, whether the current brands of ‘self-help’ publications may or may not have something to offer us as martial artists.

Sun Tzu – The Art of War.

If anything can be clearly categorised as being a ‘martial arts’ book it has to be Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Said to have been written around 500 BCE, this short text contains a wealth of martial knowledge and strategy. [1] The beauty of the book is that it is broad in its application and scope, yet detailed enough to pick out examples for reflection; and it plays with the conceit of being applicable to individual combat and battles involving large numbers.

People in the west have been aware of this book for as long as there has been an interest in orientalism, and inevitably it has been appropriated by the business world. So many spin-offs telling us how Sun Tzu’s book can be applied to the cut and thrust of the high-powered boardroom -everyone is looking for an edge. Titles appeared like, ‘Art of War for Executives’, ‘Sun Tzu – Strategies for Marketing’, etc, etc.

Musashi Miyamoto – ‘The Book of Five Rings’.

Musashi’s terse book on strategy and fighting suffered a similar fate to Sun Tzu. I have mixed feelings about the Book of Five Rings. At least one Japanese Sensei I have spoken to has been puzzled about Musashi’s status, as in, ‘why this guy?’, ‘Why does this dubious character deserve so much attention, when there are so many more elevated examples… Katsu Kaishu was an amazing model, yet nobody talks about him?’.

I have seen ‘the entrepreneurs guide to the Book of Five Rings’ and others have tried to piggyback on this book of ‘wisdom’.

Musashi was a product of his age, and in terms of Darwinian principles, managed to stay alive through sheer cunning and an unorthodox approach (though, what was orthodoxy in that age is very fluid. 16th century Japan was like the wild west). Again, you have to understand the context.

A quick note on the ‘Warrior’ mentality.

Excuse me for my cynicism here but nothing grinds my gears like the overuse and appropriation of the word ‘warrior’.

As a ‘meme’ on the Internet all these ‘warrior quotes’ are guaranteed to cause me to gnash my teeth in anger and frustration.

Musashi ‘quotes’ abound (which end up as not ‘quotes’ at all, just some made up cobblers nicked from another source). [2]

Just what do people mean when they refer to ‘Warriors’ anyway? Are we talking about the modern context; the professional soldier? If so, the gulf between that model and the model presented by someone like Homer when he introduced us to Achilles and Hector, or, in Japan the stories told about Tsukahara Bokuden (1489 – 1571) [3] is just too huge a gulf to be bridged; different worlds, different mentality, different technology. Unfortunately, the romantic appeal of BEING a ‘warrior’ attracts precisely the same people who lack all the idealised and fictional attributes of so-called warriordom, a domain for fantasists and keyboard heroes. Sad, but true.

To return to books.

‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’

I know that I have mentioned in a blog post previously about Inazo Nitobe’s ‘Bushido – The Soul of Japan’ book. Essentially it is a confection running an agenda, in that Nitobe wanted to build a cultural bridge between Japan and the west with a distinctly Christian bias (he was a Quaker). He created an overblown link between the romanticised ideal of medieval chivalry and an equally fictionalised picture of the ‘code of the Samurai’; as such, in a nutshell, ‘Bushido’ was a modern invention. I’m sorry, but somebody had to say it.

‘Zen in the Art of Archery’.

Although this book has been influential for some time it also suffers criticism not dissimilar to Nitobe’s book. Eugen Herrigel, wrote the book after his experiences with a Japanese Kyudo (archery) teacher, Awa Kenzo. Herrigel was teaching philosophy in Japan between 1924 to 1929, the book was published in Germany in 1948. My view is that Herrigel’s achievement in writing this very short book was that he introduced the element of spirituality linked to Japanese martial training to western thinking. Although I feel a need to offer a disclaimer here… Herrigel has taken some flak (posthumously, he died in 1955); intellectual big guns like Arthur Koestler and Gershom Scholem pointed out that in the book Herrigel was spouting ideas that came from his connections with the Nazi party.

Yamada Shoji in his book ‘Shots in the Dark’ suggests that Herrigel had got it all wrong and that the ‘Zen’ element was embroidered into the story. Yamada also tells us that conversations Herrigel had with Awa Sensei were either misunderstood or simply didn’t happen.

The title alone spawned homages to Herrigel’s book – ‘Zen and the Art of Motocycle Maintenance’ comes to mind. Also, in a previous post I mentioned ‘The Inner Game of Tennis’ by Gallwey; it was Herrigel’s book that inspired Gallwey’s thinking; so, let’s not give Eugen Herrigel too hard a time.

Western books that may be relevant.

Rick Fields books are quite interesting, one in particular. Don’t be mislead by the title (based on what I’ve said above) but ‘The Code of the Warrior – in History, Myth and Everyday Life’ is a really engaging read. Fields gives us a potted history of the urge to take up arms, from the prehistoric times through to Native American culture and even a chapter on ‘The Warrior and the Businessperson’, looking at Japanese business methods and their link to samurai mentality.

Rick Fields other books have a more spiritual dimension and tend to look dated and New Age in their outlook, (written in the 1980’s); ‘Chop Wood, Carry Water’ has a clearly Buddhist vibe with a touch of the ‘Iron John’ about it. [4]

Self Help books.

Although not specific to martial arts training the so-called ‘Self Help’ book explosion may have some useful cross-overs. I had previously written a book review for ‘The Power of Chowa – Finding Your Balance using the Japanese Wisdom of Chowa’ by Akemi Tanaka. There are other books encouraging us to lead better lives that have a base in Japanese thinking, but Tanaka’s book has a clear objective of helping people to restore a meaningful balance in their lives.

I know other martial artists I have spoken to have found certain authors useful in contributing to the spiritual side of their martial arts experience. To mention a few:

- Stephen Covey, author of ‘Seven Habits of Highly Effective People’. I haven’t read it but I did read his book, ‘Principle Centred Leadership’. My takeaway from that was how much Covey was borrowing from other sources – some stand-out examples seem to come from Taoism; but useful nevertheless.

- A raspberry from me for Richard Bandler, I am suspicious of anything from him and his followers; he is one of the originators of Neuro-linguistic programming (NLP). It is, essentially pseudoscience and latest neurological research suggests that Bandler is barking up the wrong tree.

- Following a Zenic direction, Eckhart Tolle’s descriptions of the benefits of ‘living in the Now’ are worth taking a look at (though avoid the audiobook version of ‘The Power of Now’, unless you suffer from insomnia; his voice is one continuous flat drone).

- Followers of this blog will perhaps have realised that I have a lot of time for Jordan B. Peterson; however, only three books have been published [5], but the online lectures are solid gold. Peterson has some interesting thoughts on serious martial artists, who he talks about in his references to the Jungian concept of the Shadow.

The Dark Arts.

This post would not be complete without mentioning what I have called ‘the Dark Arts’. These are almost exclusively western in origin. I am not really sure where I stand on the efficacy or even the morality of these publications, but here is a list:

- ‘The Prince’, Niccolo Machiavelli 1532. The vulpine nature of Machiavelli just oozes off every page. He was a master of deception and treachery, a minor diplomat in the Florentine Republic. ‘The Prince’ is a masterwork for anyone who wants to succeed at any cost. But you might want to wash your hands afterwards.

- ‘The Art of Worldly Wisdom’ Baltasar Gracian 1647. Similar in nature to ‘The Prince’. Gracian was a Spanish Jesuit priest. Winston Churchill was said to be inspired by this book. It is dedicated to the arts of ingratiation, deception and the cunning climb to power. Just as apt today as it was then.

- Contemporary writer Robert Greene is perhaps the inheritor of Machiavelli and Gracian; in fact, he borrows heavily and unashamedly from these sources. He initially shot to fame with his 1998 book ‘The 48 Laws of Power’. The titles of his books always suggest to me as a mandate for roguery and look to all intent and purposes like a villain’s charter, as an example; ‘The Art of Seduction’ 2001 and ‘The Laws of Human Nature’ 2018. This put me off, that, and a conversation with my barber who seemed to enjoy the salacious nature of Greene’s ‘words of wisdom’. But I listened to Greene interviewed on a podcast and my view changed. Having now read ‘The 48 Laws of Power’ I realised that Greene wrote this almost from a victim’s perspective and I saw in it mistakes I had made in my past and have since bitterly regretted. A useful and humbling experience. There is more humanity in this book than I initially assumed – but also a good measure of naked ambition and dirty dealings, if you like that sort of thing.

Clearly this is not a comprehensive list of everything out there, just things I wanted to share. I think there are many martial arts people who want to look beyond the physicality of their discipline and have an urge to find a wider meaning to their efforts – which is entirely in line with the broader scope of Budo, as envisioned by Japanese masters like Otsuka Hironori, Kano Jigoro and Ueshiba Morihei.

Follow your curiosity and enjoy your reading.

Tim Shaw

[1] The Penguin ‘Great Ideas’ edition is a mere 100 pages in length, with each page consisting of very short stanzas – a very simple read.

[2] The only time I felt inclined to use a ‘warrior based’ quote was a very apt one that I quite liked, “The nation that will insist on drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking done by cowards”. Thucydides.

[3] Bruce Lee’s ‘Fighting without fighting’ scene in ‘Enter the Dragon’ was stolen straight from stories about Tsukahara Bokuden.

[4] ‘Iron John – A Book About Men’ by Robert Bly. The author attempted to rescue the soul of masculinity, this was intended as an antidote to the excesses of feminism (well this was 1990!) but it was ridiculed and derided in all quarters as it became associated with all the ‘sweat lodge’, ‘male bonding’ razzamatazz, that might have been quite benign, although misguided, but quickly turned into something darker.

[5]. Jordan B. Peterson books; ‘Maps and Meaning’ (a demanding read), ‘Twelve Rules for Life’, (much easier to read and really relevant) and the latest book, ‘Beyond Order’, also good.

Image: ‘St Jerome in his study’ by Albrecht Dürer 1514. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

How detailed is your Wado map?

How confident are you about what you know of your system, the discipline you have chosen to study? Are you comfortable with the information you currently have to hand? Do you think you understand the roadmap of that developing knowledge, and is its trajectory obvious and predictable?

Okay, so, I accept that any Wado practitioner reading this might well be at very different points in their journey; some may be just beginning their study, others might be senior practitioners with many years behind them, but the ideas I am going to put forward I am fairly sure would benefit all – or at least stop and make you think. That’s the plan anyway.

Maps.

I am going to start with the broader idea, something I heard a little while ago. There is a theory that we all keep a complete map of the world within our own heads – a personal hardwired version like Google Satellite, Street View and Maps. When I first heard this, I was sceptical.

While I am fully aware that the human brain is perhaps the most complex thing on the planet but really this seemed a bit too far-fetched. But, it is true. That mess of grey matter that sits between our ears that has no awareness of itself outside of its own input devices – our senses, can really do all that, and more!

This amazing mapping, navigation device does not just include places, it also acts as our own personal encyclopaedia, with just about everything there is to be referenced. I use the word ‘referenced’ in a very deliberate way because the reality is that ‘references’ are about all we get.

To explain; while we have this map/encyclopaedia in our head most of this information is patchy and, in many cases, extremely low-resolution. The truth is, we have low-resolution representations of the majority of things we think we know.

Examples:

- Ask yourself about a random country in the world; say, Vietnam? Can you point to it on a map? Probably, but what else can your personalised encyclopaedia tell you? History, culture, language, currency? Unless you know the country very well through direct experience your knowledge will be sketchy, very low-resolution.

- Another couple of words; ‘Steam Train’. To communicate your understanding of this mode of transport, you might draw me a picture of a steam train, complete with funnel and wheels and a cab, all very ‘Thomas the Tank Engine’ – but unless you are an insanely enthusiastic trainspotter with qualifications in engineering and skills in mechanical draughtsmanship, I am not going to be convinced that you really understand a steam train, it will be extremely low-resolution.

Okay, so there are things we might be VERY knowledgeable about (or THINK we are), but the reality of our ‘wired-in’ intelligence and retrieval system (brain) is that it is in a state of constant update, or at least it should be. The truth is that (hopefully) more depth of information is being added and redundant (false) files are being deleted or replaced and new entries or categories are being added.

In some areas, people actually choose not to update their maps and files, this is often found when people become entrenched in areas like politics. Clearly, individuals can be so profoundly tribal in their political beliefs that even in the face of irrefutable evidence they will argue that black is white. But that’s their problem.

How about Wado (or any martial arts system)?

All of the above can be applied to our understanding of Wado karate.

I think it’s a case of being totally honest with yourself; particularly those who have been on this pathway a long time. Come on, do you really believe the same things that you did twenty years ago? How have your files been updated?

An example:

I came to the conclusion a long time back that just about everyone I knew in the martial arts continued their training for completely different reasons than those they started with. It might have been that they initially wanted to build confidence; they were fearful about their ability to protect themselves; but then, over time, their maps changed, their references became more sophisticated, more nuanced and they found something new, something of substance. I can’t get into describing what that is in this post, I don’t have the space; (in some ways I explored this idea in my blog post ‘Martial Arts training and the value of finding your Tribe.’).

Your Wado map.

For every student of Wado karate your initial ‘map’ is usually found in the pages of your syllabus book. This map expands as you move through the grades. Although, I must say, the reality is, it’s not an easily accessible map because it is mostly written in a different language.

But it would be naïve to assume that when we have completed the book we have mastered the system, it doesn’t work like that. The syllabus is a very low-resolution representation of the system; really, it’s a loose framework designed for convenience. In addition, ‘knowing’ the book, with its Kihon, Kata and Kumite doesn’t guarantee you can actually do it; and doing it doesn’t mean you can apply it. Imagine a musician who can read sheet music but can’t play an instrument, or who can play the music accurately but cannot improvise!

The downside of the syllabus book.

In Wado I don’t think reliance on the syllabus book is particularly helpful; it’s a pretty poor map. For me it’s too linear. For systems other than Wado it might easily describe the structure in a straightforward and accurate way, but within Wado karate it only takes you so far in understanding the true nature of this very unique Japanese Budo system. In fact, I would go so far as to say that if the book is the only model/access route, it will ultimately lead you down a dead end. [1]

A different map.

In some of my more recent teaching seminars I have presented a completely different map; a pictorial diagram that I think enables Wado students to navigate a more useful and meaningful way of understanding Wado – but a blog post like this is not the place to share this idea; besides, it is still a work in progress, as it should be. [2]

Expanding the map or increasing the resolution?

I think it is too easy to misread what I mean by developing or expanding the map. I don’t think that the Wado map should be seen as a kind of growing, territorial colonialisation, similar to a video game like ‘The Settlers’ or ‘Minecraft’ where from a tiny localised centre you keep occupying new territory and building new structures; that would be like adding extra pages on the end of the syllabus book.

To give a concrete example: Otsuka Sensei was quite content with the idea of nine core solo kata, anything beyond the apex kata of Chinto was classified as ‘extra’. [3]

Paired kata are perhaps another story. If you take them on face value, they are legion! But to focus on their bewildering number is perhaps missing the point.

I speculate that with the paired kata there is a hidden map lurking beneath the seemingly complicated map which features, for example; the ten Kihon Gumite, the thirty-six Kumite Gata, twenty-four Ura no Kumite and all the rest. The clue is when you acknowledge the reality that none of these paired kata contradict the core principles, and it is these core principles that are the real map, the one skulking underneath, and, in content, the ‘Principle Map’ is not such a huge numerical challenge.

The most valuable approach is not necessarily to expand the territory, but to increase the resolution. The territory might well push beyond its boundaries but only in a natural, unforced way, an organic by-product of more defined and focussed examination. The real payback is in the more granular exploration of areas you already think you know.

‘Low-resolution’ has its uses.

Low-resolution thinking is natural to us, it’s the very basic of what we needed to survive and has been with us for tens of thousands of years. But what might have been paramount for hunter-gatherers has now slipped down our list of priorities – I mean who needs to clutter up their thinking about what they might have had for breakfast when they are being chased by a sabre-tooth cat? A boost of adrenalin and the most basic info about an escape route should be enough!

What does ‘increasing the resolution’ mean for your Wado?

Let me start with what it does NOT mean:

- It does not mean knowing more and more about less and less.

- It does not mean you become a slave to detail, which, if taken to its extreme can result in you looking like an obsessive dilettante, all ‘head knowledge’ and no practical/physical skills. [4]

- It does not limit your thinking by allowing you to assume you have it all pinned down. Actually, the reverse should happen; your mind continues to expand.

What it DOES mean is:

- The more granular your understanding the more you appreciate the relationships between the various parts of your Wado map, the underpinning logic.

- This increased resolution enhances your creativity.

- If approached with humility, you begin to realise how little you know, or how things you thought you knew might have been wrong.

How to adopt a ‘granular’ approach to something you thought you knew.

As an example; never, never, never underestimate or dismiss Kihon, I say that because if you take something like the action of Junzuki, this single technique taught at the beginning of your training reveals so much more depth. Why do you think that no matter how many years you have been training you never leave Junzuki behind, you never transcend it? It’s always a work in progress.

But I guess you expected me to say that.

Another example: Take something like the role of ‘Uke’ in paired kata… it took me far too long to realise that Uke is not a mere stooge for the person performing the prescribed technique. Uke has more say in the conversational process and this ‘conversation’ continues all the way to the end of the kata.

The double-edged sword.

I left this part till the end, but it is incredibly important. Essentially, having knowledge in your head is no good on its own. For it to be given any form of concrete real-world potency, the other form of ‘knowledge’ must accompany it; that is the absorption of the technique into your body, to borrow someone else’s rather excellent description; it must be so deeply engrained that it stains your very bones!

Tim Shaw

[1] Yes, we have a syllabus book in Shikukai, and yes it has its uses as an outline, a catalogue of techniques and requirements for grading, but that’s it.

[2] I have been toying with the idea of sharing this type of material through a subscription service like Substack, but I haven’t made my mind up yet.

[3] Notice how the kata Suparinpei dropped off Otsuka Sensei’s map very early on. Also consider Otsuka’s early development of Wado and look at the list of techniques produced for the official registration in the 1930’s; it’s a kind of map, but what was its objective? Who was the map really for?

[4] ‘Dilettante’, I like this much underused word. Definition; ‘A dilettante was a mere lover of art as opposed to one who did it professionally.’

Photo credit: The Settlers screen image courtesy of: https://www.sockscap64.com/games/game/the-settlers-2/

Competition karate – Is this really the way it’s going?

Looking at the latest manifestation of karate as a competitive entity I honestly wonder where the current trends are taking us?

This is a genuine question; I’m not saying I have answers, but I am going to try and unpack my own thoughts through the process of writing.

First; examine my image at the top of this post. Is there any truth in this view? Is competition karate turning into an empty-handed version of Olympic fencing?

For me this came out of a conversation I had while teaching in Europe. An instructor, who is much more engaged with the modern competition scene than I am, proposed this comparison to me, and I was quite shocked really. Since then, my Instagram feed of seemingly endless competition karate training drills, contest clips etc, have all taken on a different guise – once the thought hit me I couldn’t un-see it, this looked like fencing!

Maybe others have come to the same conclusions?

In the process of writing this post I discovered that ‘Karate Nerd’ Jesse Enkamp had also dipped into this area, and, in part, came up with a similar comparison [1]. In this mini-documentary, as an interviewee, he presented an interesting comparison between competition karate from the 1980’s and 90’s and the most modern version. At one point he said that the 1980’s/90’s example featured competitors who were ‘determined to win’, while modern competitors are ‘determined not to lose’. The point he seemed to be making acted as a reinforcement of an observation that modern day karate competitors are so wired that they seem to be perpetually on a knife edge; with the suggestion that perhaps those historical competitors, in their crudity and aggression, could somehow disregard this necessity? I have my doubts.

Perhaps it’s more complex than that?

Maybe it is the pressure of the modern competitor to ‘not lose’ by points alone; whereas his historical counterpart would perhaps ‘lose’ in more than just one way? For example, he might experience loss by, sheer domination or aggression, or just being purely physically overpowered by strength or prolonged staying power AND lose on points? [2]

Mindgames.

The modern competitor surely must be developing a mindset similar to that of a top seed tennis player? I would refer anyone interested in this to Timothy Gallwey’s ground-breaking 1974 book ‘The Inner Game of Tennis’. This book launched a whole industry of peak performance sports psychology, focussing on cultivating a mental state which enabled the highest level of sporting achievement. Interestingly Gallwey ‘discovered’ these techniques through exposure to meditation back in the 1970’s; now where does that sound familiar?

Specialisms.

The modern karate competitor is a specialist; the concept of the ‘all-rounder’ (the person who wins both the kata and the kumite) probably died in the 1980’s, and in those days, they had to prove themselves through huge, continual rounds of eliminations, not in some minor domestic contest.

You can’t take it away from them, as a specialist the modern karate contestant has developed superb athleticism, clearly the domain of the very young. Remember, what the Olympic fencer does with one hand (albeit with a 110cm extension) the karate athlete has to do with all four limbs; that is a heck of a lot to have to look out for!

‘Karate Combat’.

A final word on ‘Karate Combat’, a new franchise/business/media phenomena developed in 2018. An unashamed crossover between sport and showbiz, whose founders credit the emergence of ‘Cobra Kai’ as contributing to their ‘timely’ success.

My view is that if you stick around long enough the same ideas roll round time after time. This same idea was happening in the 1970’s; the American version at that time made stars of Benny ‘the Jet’ Urquidez and Bill ‘Superfoot’ Wallace. This is almost the same, only packaged for the ‘Mortal Kombat’ generation, with all the modern digital glitz.

It is interesting what COO/President of Karate Combat Adam Kovacs has to say about his product: “This is something that karate itself has been kind of crying out for in a way, because anyone with a background in karate beforehand would have only had the option to switch to mixed martial arts, whereas now if they want to fight full contact they can put their years of training to the test at the highest level….We think we are not only doing a favour to karate but also to the entire martial arts community who have grown tired of the copycats because pretty much every single one of these other promotions are trying to copy what the UFC is doing”. [3]

Bear in mind that Kovacs was a successful Hungarian sport karate competitor from 1998 to 2010. I have watched a little of the Karate Combat output, but always come away with the same nagging doubts; particularly, why is it that the fighters have to compromise their technical karate base (if we assume that’s where they came from) to be successful? Even the great modern karate competitor Rafael Aghayev has to depend on the wildest haymaker punches to make it work, to generate the power? [4]. To my mind Aghayev is a full-on class act, but my guess is that in this particular arena he has to resort to the common mode. Maybe it’s not so much a reflection of Karate Combat or Aghayev and the other competitors; perhaps it’s a reflection on the current mode of sports karate?

Like I said at the beginning, I am still working this out, all I can come up with is observations and questions, but no conclusions. But, just where are we going with this? After all, the Olympic karate pony never really got to the starting gate – good thing or bad thing? You can make your own mind up.

Tim Shaw

[1] ‘Martial Arts Journey’. Old school karate link

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SYp3BLXYBsk

[2] What is interesting about the examples of ‘old school karate competition’ is that they seem to be mainly from the UK. Look out for Alfie ‘the animal’ Lewis in that very interesting foray where, then karate England manager, Ticky Donovan decided to field a freestyle ‘star’ of his age, as a karate competitor. It didn’t work because Alfie operated in a very different format – I think you can see that in the footage (those of you who can recognise Alfie Lewis).

Also watch, Elwyn Hall, Shotokan KUGB supremo.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E7KYvluiN-k

Fencing photo credit: https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/sports/fencing-france-roc-face-off-mens-team-foil-gold-2021-08-01/

Karate photo credit: https://www.ispo.com/en/markets/everything-about-karate-premiere-olympic-games-tokyo-2021

[3] Karate Combat Interview Adam Kovacs quote: https://www.givemesport.com/1719277-karate-combat-is-carving-out-its-own-path-in-the-crowded-space-of-combat-sports

[4] Watch Aghayev’s Karate Combat bouts on YouTube slowed down and you will see what I mean.

Martial Arts training and the value of finding your Tribe.

I think everybody has heard the saying, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts” [1] attributed to Aristotle. It is a useful phrase when applied to the accumulated value we get from our martial arts training, and particularly when we look at the way our various organisations endeavour to support us in our ambitions and travels along the Martial Way.

I want to look at this contribution from the individual martial artist’s memberships and loyalties to their organisations, as well as to the allegiances and bonds they feel towards their fellow trainees who accompany them on their journey – this I will call the ‘Tribe’.

Your Tribe (sources and references).

It is not an original idea, it’s certainly not my idea. For this I am indebted to the book, ‘The Element – How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything’ by the late Sir Ken Robinson (with Lou Aronica) [2].

There are so many interesting and inspirational parts to this book, but I will just focus on just this one, as I feel it is maybe something we should make a conscious effort to appreciate and understand, and, if you are in the upper hierarchy of your martial arts organisation, it is worth taking this seriously, as it applies not just to you, but also to every one of your students no matter what their age or level.

In this book Ken Robinson makes a huge thing about the importance of ‘Tribes’ for enabling human growth through finding what he calls ‘your Element’, as in, ‘being in your Element’ and finding the true passion in your life. This could be through anything; through sports, through the arts or the sciences, but, although it is possible, you might struggle to thrive and develop in total isolation, the energy you get from being part of a Tribe of people all working towards the same thing is truly empowering.

Here are some of a huge list of benefits.

You could start with what it means to share your passions and connect with others; the common ground and the bonding has a power all of its own.

Antagonists – the grit in the oyster.

Within the Tribe you meet people who see the world as you do, they don’t have to totally agree with you, but you are in the same zone. In fact, disagreeing with you can create a useful friction and even challenge your established views, which in itself promotes growth.

Collaborators and Competitors.

Robinson says that in the Tribe you are liable to meet collaborators and competitors; a competitor isn’t an enemy, it is someone you are vying with to race towards the same goal, and as such that type of tension can energise you, and the heat of battle (competition) inspires further growth, it’s a win-win.

Also, if your competitor has a different vision, this vision can help to validate your personal goals and either justify or revise your overall views.

Inspirational models.

Tribe members can act as motivators, their acts and sacrifices can inspire you, and remember, the positive relationships don’t have to be vertical, as in looking up to your seniors; but also horizontal, seeking inspiration from your peers. Of course, it is entirely possible that your tribal inspirational models might include people who are no longer around, I include past martial arts masters and not necessarily the ones you have been lucky enough to meet.

Speaking the same language.

Being in the same tribe means that you have to engage in a common vocabulary, but you also have to develop that language to explore ideas.

Your tribe members may perhaps force you to extend your vocabulary, to deal with more complex or nuanced aspects of what you are doing – very obvious in the martial arts, as some of these concepts might be outside of your own cultural models. I can think of many times when talking with fellow martial artists that my descriptions seem to fail me, and then someone will come up with a metaphor I’d never thought of, an inspired comparison or natty aphorism which just sums it up so neatly, and, of course, I will shamelessly steal it. You couldn’t do that on your own, you have to have the sounding boards, the heated debates, or even the physical examples (because, not everything happens at the verbal level, in fact we thrive on the physicality of what we do!).

Validation.

This is something that the martial arts have the potential to do particularly well. I say ‘potential to’ because it seems to almost be taken for granted. I believe that the frameworks used, particularly in karate organisations, are a good example of how to support, validate and acknowledge the individual student’s dedication to their training.

Done properly, this happens in two ways; the first being the official recognition of achievement, an example might be, gradings, which act as a rubber stamp and are generally accepted across the wider martial arts community. In individual or group achievements we are respectful and genuine in applauding our fellow students, which adds real value and meaning to all the blood, sweat and tears and makes it all feel worthwhile.

The second way is more subtle though not lesser in value, and that is related to the softer skills, the buzz of being shoulder to shoulder, the unspoken nod from your instructor or your fellow trainees, the respectful bow, all of these send signals that validate and add value to your membership of the Tribe.

Being in the right Tribe.

Of course, it is entirely possible that you might find you are in the wrong Tribe. There might be something about it that is just doesn’t work for you. If that’s the case then a great deal of soul-searching may have to take place. I suspect that in the past this same ‘soul-searching’ for some people can take far too long; as the saying goes, ‘What a tragedy it is that you’ve spent so long getting to the top of your ladder only to find that it’s propped against the wrong wall’.

You will know that you are in the right Tribe when it ticks all the boxes; not just the above points, but also you will notice that your creativity is boosted, your life feels energised and given meaning.

The Tribe is the fertile soil of personal growth. Robinson says that “Finding your Tribe can have transformative effects on your sense of identity and purpose. This is because of three powerful tribal dynamics:

- Validation.

- Inspiration.

- ‘The alchemy of synergy’.”

I write this at a time when tribes are just beginning to re-emerge after the pandemic. There has never been a more apposite time to appreciate the value of your tribe – just look for the smiles the first time the whole tribe truly gets together.

Tim Shaw

[1] For anyone interested, it is a key aspect of those who support the Gestalt theory in psychology and the concept of ‘Synergy’ (definition: ‘the interaction or cooperation of two or more organizations, substances, or other agents to produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate effects’. Oxford Languages definition).

[2] ‘The Element – How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything’ by the late Sir Ken Robinson (with Lou Aronica) https://www.amazon.co.uk/Element-Finding-Passion-Changes-Everything-ebook/dp/B002XHNMVM

Personal Security and Society, a Different Perspective.

On the back of the earlier blog posts about self-protection, I thought I would try and look at the bigger picture; particularly as it relates to society.

While I have no qualifications in sociology, criminology or demography I want to present some different ways of looking at things.

The main thrust of this post will be to put forward a series of models that may well clarify a few points and maybe explode a few myths. I will back this up with examples from various sources.

A few basics.

It goes without saying that the reasons for our success as a species is our ability to collaborate, communicate and work as a group to get stuff done with the minimum of friction [1].

To do this you need agreed sets of rules, which over time solidify into laws that we all have to agree to abide by if we want to live within our tribe/society.

And then there are whole swathes of unwritten social nuances which oil the wheels and involve social protocols, good manners, respectful behaviour and not giving in to the destructive, selfish aspects of our basic impulses. We rein ourselves in because we are mindful of the impact of our behaviour on those around us and how that affects our relationships and status in the group. For humans this is incredibly complex, at both the formal/legal level and the more fluid, unwritten domain.

The Framework.

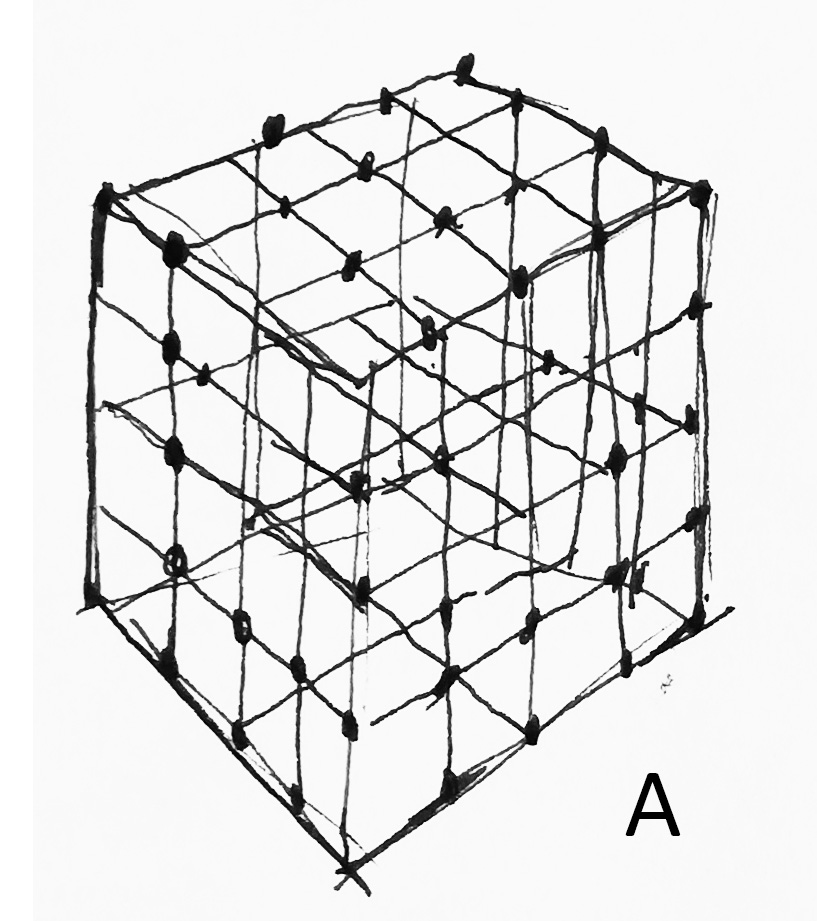

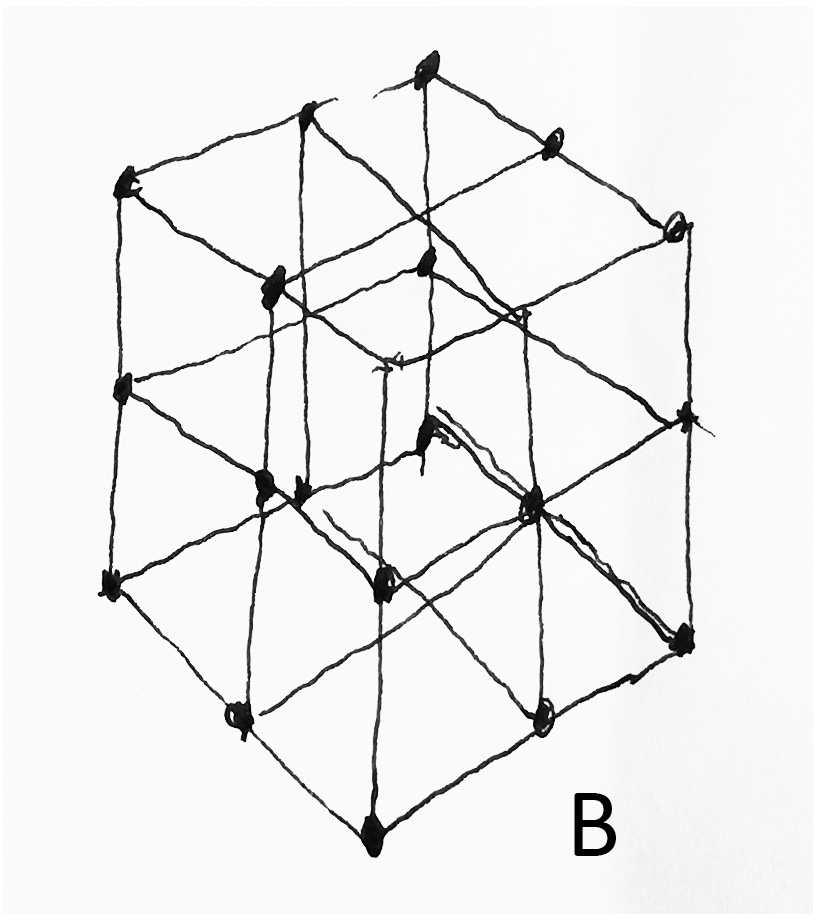

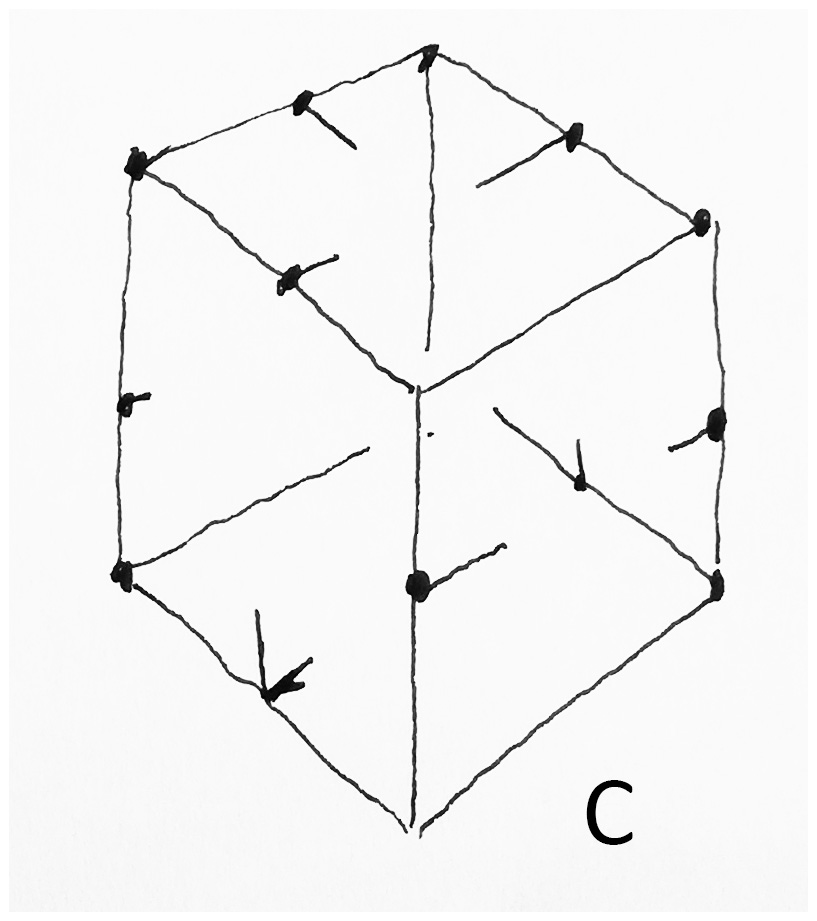

In my mind’s eye I see this as a framework. For me society is like a complex cuboid mesh, of which the strands that hold it together are both our guidelines and our constraints.

Young children grow learning to gradually adopt and navigate this framework. In their very early development it is the parents who construct and manage a world for the child that balances their needs and wants (and freedom of personal expression) and steers them towards what society expects of them.

Gradually these young children become civilised and the process continues to unfold all the way through from their home life to their schooling.

They are expected to create and navigate friendships, as well as stay within the gridlines of first; nursery, then junior school, secondary school and ever onwards. All of these institutions have a secure and complicated framework, which needs to be navigated if they are to survive and thrive. It can be disastrous for a child to fail in this responsibility (for whatever reasons), if they do, they risk being unpopular, ostracised, seen as literally an ‘outsider’ (outside ‘the grid’), which, if left unchecked or unsupported, can breed bitterness and resentment, where any perceived faults are projected outwards onto the big bad world and the people who inhabit it. In its most extreme example, it can lead to events like the Columbine High School shootings of 1999. [2]

Schools as the archetype of ‘the Grid’.

From my experience schools are typical and easily observable examples of this complex gridded cube.

I have seen this first-hand; particularly over the last three years, as a career turn has taken me inside over twenty UK secondary schools, where I have been able to observe them up-close and across all levels.

The ‘framework’ in schools is so very obvious, it even exists as a physical reality – look at the way architects, past and present, design schools. It is manifest in the box-like rooms all stacked on top of each other, connected by corridors and stairwells; even the outdoor spaces tend to be designed to constrict and control; the imagery of the grid is everywhere.

In the last ten years the physical structure of schools has become even more boxed-in; often for what is seen as very good reasons, reasons of ‘safeguarding’ and ‘well-being’, but you have to wonder, has the world become so much more of a dangerous place?

In an ever-escalating arms race of ‘security’, how big is the threat? Does it warrant the explosion of things like; key-coded exterior security gates and fences (are they to keep people out, or to keep people in?); doorways between corridors having to have swipe-card entries; everyone forced to wear lanyards with ID pictures, and (I kid you not) even lock-down zones with metal shutters that grind-down on the press of a panic button, and metal-detector gateways! [3] I have seen all of these.

You have to ask yourself, is this care and kindness geared towards the well-being of children, or is it thinly disguised paranoia that further feeds into the anxiety of young people? What messages are we giving them?

Within the constraints of this tight and complex mesh we are hoping that young people will be able to experience some freedoms and some elements of self-expression, where they can carve out their own unique identity (which, in the UK, is somewhat negated by the contradiction and oddity of the enforced school uniform![4]) I am sure that self-expression happens, but only in the gaps between the gridlines.

Where does the responsibility lie?

It seems to me that headteachers and governors are engaged in a Top Trumps game of who can outdo who in the personal security/safeguarding checklist. I just don’t think they have thought it through.

Safety in the wider world.

What happens to young people when school is no longer part of their lives?

One could suppose that as they have reached adult status the grid is a more open structure, certainly compared to schools.

It might be worth considering the example of the recent red flags that have gone up in UK universities where the apparent slackening of the grid has brought about what seems to be an epidemic of sexual predators – what is the truth behind the reported stories? Why has it been proposed that undergraduates have to have ‘consent training’ etc? [5] Is this a failure of the system, or an inevitable malaise unwittingly constructed by the system itself?

On top of this you have to ask yourself, do these young people have everything they need to survive and thrive, to navigate the bigger open-mesh of society and stay out of harm’s way? Has their education and upbringing given them the necessary tools?

They seem to lurch forward into the adult world with their parent’s words of warning ringing in their ears; but the irony for parents is that a mother’s advice to her teenage daughter as to how to stay safe on a Friday night out with friends is often based on what it was like in the 1990’s, so unless she’s got a time machine, it’s not going to be very helpful. The world changes at a phenomenal rate.

Not all grids are the same.

The societal structures (the grid patterns) are not the same all over the world; yes, they deal with the same basic issues of safety and rules but, for example, the gridlines in Birmingham UK are very different from Tijuana Mexico. (Or even Sarasota Florida).

A cautionary tale about grids.

In 2011 two young British men, James Cooper 25 and James Kouzaris 24, while visiting Mr Cooper’s parents in Sarasota Florida decided to cut out on their own after an evening meal out. They were more than a little drunk, and wandered into a run-down part of Sarasota, a place called Newtown. It appears that Newtown is where the gridlines run out of road.

To cut a long story short, Cooper and Kouzaris were found dead at the side of the road. They had been shot by local boy Shawn Tyson 17, there was no sign of robbery, they both had wallets with money and phones; they just strayed into a blind spot on the grid, one which the locals of Sarasota and Newtown would have surely known about. [6]

This scenario would be unlikely to play out the same way if they were stumbling around Surbiton or Guildford at two in the morning, because they’d recognise the situation, understand their options and be able to navigate the gridlines that were available to them, while calculating the potential of threat or risks inherent to that particular scenario.

Sadly, it is unlikely that any amount of martial arts or hands-on self-defence training would have saved James Cooper and James Kouzaris.

Final word on terrorist threats.

This is a classic case of ‘head says one thing, but heart says another’, but statistically you’d have to be pretty unlucky to get caught up in a terrorist attack in the UK. Yuval Noah Harari the Israeli historian describes terrorism as ‘a puny matter’ when compared to what happens in warfare. It is essentially all spectacle and theatre designed to stoke up fear, and it does, just think about the example of the emotional and human after-effects of the Manchester bombing in 2017.

Essentially, governments and media do the terrorist’s work for them, they supply the oxygen to these combustible situations, and unintentionally become the recruiting sergeants for the next generation of terrorists through ill-thought out knee-jerk reactions. But, as they know, you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t.

Read Yuval Noah Harari’s piece in the Guardian, for a good description of how this works at a rational level.

Keep safe.

Tim Shaw

[1] As individuals in the animal kingdom we make pretty lousy predators; we are not particularly strong, agile or bulky to survive on our own without the employment of weaponry, and even then we have to operate in packs to achieve any level of success.

[2] Columbine High School Shootings https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbine_High_School_massacre

[3] Most schools I have visited have ‘lock-down procedures’, some have interior door wedges with the fear of the possibility of an ‘active shooter’, and this is the UK not the USA. The UK has only ever experienced three school shootings and all of the casualties (bar 1) occurred in just one incident. Compare that to the USA, where between the year 1999 and 2012 there have been 31 school shootings.

[4] Radical educationalist professor Guy Claxton said that schools tend to be constructed on one of two models; the are either ‘monasteries’ or ‘factories’. ‘Monasteries’ have; authorities in gowns/robes with other robes/uniforms for novices and are based upon some vague notion of revelation, with a massive worship of ‘tradition’. While ‘factories’ have bells to end shifts and have the intention of turning out identical little ‘products’ and are judged by quality controllers (Ofsted, Performance management etc), they won’t admit it but they are really exam factories. I know this because for a long time I worked in a factory that was built on the ruins of a monastery.

[5] Consent training and even ‘Good Lad workshops’ in universities and colleges. See this link from the University of Cambridge https://www.breakingthesilence.cam.ac.uk/training-and-events/training-students

[6] Murder in Florida, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-17479559

You’d better hope you never have to use it – Part 2.

“Smash the elbow”, “tear the throat out”, “snap the arm like a twig”, “gouge the eyes with your thumbs”. I have heard these things said by martial artists during classes. But I find myself asking, how do you know? and have you ever done that? Have you ever used your thumbs to gouge out somebody’s eyeballs? And on top of that, how do you know you won’t freeze like a rabbit in the headlights? Or, how do you know if you have enough resilience (or lived experience) to be able to suffer a terrible beating before you get a chance to put in that one decisive game-changing shot?

Empirical evidence versus anecdotes.

Effectiveness, can you prove it? Can it be quantified in a scientific way? Is the data available?

Every martial artist probably has a dozen stories as to why their martial arts method is effective as a fighting system and none of these incidents ever happen inside the Dojo – how could they, it’s supposed to be a safe training environment?

I have my own ‘go-to’ anecdotes, but equally I have another set of anecdotes where martial arts practitioners have come unstuck – but nobody talks about those, least of all the people who it has happened to (understandably). [1].

Anecdotes may be fun to recount but all they do is muddy the water, they are too random to qualify as evidence. And, if you look at some of these stories in the cold light of day you often have to wonder about (a) their veracity, (b) which way the odds were stacked, (c) whether elements of luck or chance were involved; but one thing is clear, they cannot really be used as definitive proof that your system works, after all, the system is the system and You are not the system.

The anecdotes may suggest that in certain circumstances your chances of coming out on top in a violent attack might be slightly higher – but they could also suggest that you might come out worse (probably because of over-confidence, or an unrealistic evaluation of your own ability).

The problem with fantasy.

Now compare that to movie fantasies of physical confrontations. I cite two examples that come to mind.

The first being Tom Cruise as Jack Reacher, where Reacher takes a bunch of guys on after they offer him out from a bar ( link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hu1MtT_S3bc

The thing is, deep down, we all want it to be like that.

And then Robert Downey Jnr as Sherlock Holmes in a bare knuckles contest (link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-z5139CW1I

This last one is about as extreme an example as is needed to make my point that fantasy is fantasy. (To paraphrase Mike Tyson, ‘Everybody has a plan until they get a punch in the mouth’.)

The Sherlock Holmes example is akin to treating violence like a chess game – if I plan and think several moves ahead then my plan will bring about the downfall of my opponent…. wrong. When it gets to the ‘trading punches’ stage you have already entered the world of chaos, thus ramping up the unpredictability exponentially.

It is potentially fatal to confuse Complex with Complicated [2] and the zone of chaos is indeed Complex. This is why those who are supremely skilful at navigating the Complex world have to do it without thought, artifice or calculation, they are like expert nautical mariners in a tossing sea, who work on instinct, they have an overarching understanding of Principle, their skills are not a bunch of cobbled together tricks that they have memorised hoping for that moment to happen.

I know that there are critics of the Principle angle in martial arts (particularly Wado), usually they fail to understand it and ask, what is this ‘Principle’ thing anyway? I am tempted to reply with something like the Louis Armstrong quote about the definition of jazz, “Man, if you have to ask what jazz is – you’ll never know”. (See my blog post on ‘Fast Burn, Slow Burn Martial Arts’ for a clue as to how it works). These same people remind me of the ‘Fox with no tail’ a moral story from Aesop].

When people talk about ‘functionality’, ‘functional combative skills’, this has to be about effectiveness, surely? But You can’t talk about that without some form of measure, if there is no measure then it’s all opinion and as such, we can take it or leave it. The person who makes the statement can only hope that we trust their opinion as an ‘expert’, but again, an expert based on what experience; their ability (as proven) to ‘snap someone’s arm like a twig, or gouge their eyes out’? I realise that there are people out in the martial arts world whose whole authority rests on this issue and it’s not my place to call them out, particularly as I also have no experience of ‘snapping arms’ to support any claims I make, but just apply a little logic to it.

Of course, I reckon that if I take my opponent’s elbow over my shoulder and exert a forceful two-handed yank downwards I might be able to ‘snap his elbow like a twig’, but I doubt he’s going to let that happen without a hell of a struggle (unless I am Sherlock Holmes of course). Meanwhile, he has barrelled into me, knocked me on my back and is sat on my chest raining punches into my face, and then his mates join in to kick me in the head for good measure – elementary my dear Watson.

Looking for evidence in history.

I feel I have to address this one. Anyone who looks for evidence in history is on to a sticky wicket. History is notoriously unreliable. We know this because current historical revisionist methods are revealing that many things we thought were true may not be so. For example; everyone knows that it is the victors who write the history.

If we take our history inside Japan and Okinawa and we listen to serious, open-minded researchers, we find that some of the things we took for granted may well not be true.

To give a few examples:

- Zen Buddhism does not have the monopoly in Japanese martial arts, certainly karate is not ‘Moving Zen’.

- The 19th century Samurai were not the apex of Japanese martial valour and skill. Set that two or three hundred years earlier and you might be about right.

- Okinawan martial arts were not the result of a suppression imposed by Japanese Samurai; it was not that simple. Okinawan people were generally peaceful and society was well-structured, it certainly was not the Dodge City that some people like to suggest, it seems that the martial arts of Okinawa reflected this, an extreme martial arts crucible it certainly wasn’t, certainly if you compare it with what was happening in Japan between 1467 and 1615. I don’t point that out to discredit the Okinawan systems, it’s just an observation and there were exceptions, e.g. Motobu Choki, who certainly had his ‘Dodge City’ moments.

As time moves forward all we are left with is the mythologies, hardly something to judge the functional abilities of teachers who are long dead, so all we have available is guesswork, assumptions and opinions; not really scientific or objective. So, anyone who wants to hang their ideas on that particular hook would be wise to keep an open mind.

How would martial arts work in a defence situation? A proposition.

To answer this, I would speculate that there are several high-level outcomes that are possible, and none of them look anything like either the movie fantasy image, or the types of techniques that are, ‘a bunch of cobbled together tricks that have been memorised hoping for that moment to happen’ [3].

- The highest level has to be that nothing happens, because nothing needs to happen. The world calms down and order rules the day; chaos is banished.

- The next highest level is probably where the aggressor just seems to fall down on his own. Here are my two nearest assumptions on this (one anecdotal and the other historical – but after all, I have to pluck my examples from somewhere). The first is a story about Otsuka Sensei dealing with a man who tried to mug him for his wallet in a train station. Otsuka just dealt with the guy in the blink of an eye and when asked what he did, he replied, “I don’t know”. The other is the historical encounter between Kito-Ryu Jujutsu master Kato Ukei and a Sumo wrestler who twice decided to test the master’s Kato’s ability with surprise attacks, and both times seemed to just stumble and hit the dirt [4].

- Anything below those two levels would probably involve one single clean technique, nothing prolonged, maybe appearing as nothing more than a muscle spasm, nothing ‘John Wick’, certainly nothing spectacular – job done.

- Then you might plunge down the evolutionary scale and have two guys smashing each other in the face to see who gives up first.

Conclusions:

The original objectives of these two blog posts were to challenge the assumptions we seem have made about the nature of self-defence (in its broadest interpretation) and to put forward some different angles, explode a few myths and to present the idea that all that glitters is not gold.

I don’t have the answers, but then it seems, neither does anyone else. But we shouldn’t just throw our hands up in the air. Keep on with the focus on defending ourselves and refining our technique and by all means teach self-defence as a supporting disciple or on dedicated courses, it is a brilliant way for martial arts instructors to engage with the community in a positive and confidence building way; however, keep it realistic and not just fearful.

For those who claim that their approach has more ‘functionality’ I would humbly suggest that that you might want to look towards the key questions; objectively, how can you prove that? Maybe what you are asking for is a leap of faith? My view is that the data is not there and that it is just lazy logic. [5]

There are people who want to claim their authority from the ‘short game’, while I would suggest that there is another game in town; the ‘long game’. Targets really need to be aspirational and ambitious, not ducking towards the lowest common denominator, i.e. the ‘fear factor’ of the anxious urbanite. Your authority is not derived from your ability to ring the metropolitan angst bell; or to yank the chain of the frustrated metrosexual male who feels he is cut adrift and fretful about his role in contemporary society and lost in a maelstrom of surging confusion.

The bottom line is; get real and dare to think differently.

As a last word, these posts are not meant to be definitive, or to cover all aspects of self-protection. I could have included comments about how the law views self-defence, or how much mental attitude is a part of self-defence, or adrenalin, fight and flight etc, without even mentioning the number of young men in the UK who die through stab injuries. But maybe another day.

Tim Shaw

[1] One event happened fairly recently where I had bumped into a martial artist from another system, an acquaintance, in a nightclub. He’d had a drink or two and proceeded to bend my ear about how ‘the trouble with most martial artists is they have never been in a real fight, never trained for it, etc.’ And, as if the God of Irony was looking down upon him; within seconds of him waving me goodbye, he crossed paths with the wrong person and ended up as a victim, laid out and bleeding. I guess he didn’t get the chance to ‘snap the arm like a twig’.

Be careful what you wish for.

[2] See my blog post on Systems. https://wadoryu.org.uk/2020/01/29/is-your-martial-art-complicated-or-complex/

[3] These methods often assume that the opponent is going to present themselves like a bag of sand and allow you to engage in an ever-complex string of funky locks, take-downs, arm-bars etc. etc. Sherlock Holmes would definitely approve.

[4] Source: ‘Famous Budoka of Japan: Mujushin Kenjutsu and Kito-ryu’. Kono, Yoshinori, Aikido Journal 111 (1997). According to Ellis Amdur in his book ‘Hidden in Plain Sight’ this is pure Principle and Movement in practice (my paraphrase).

[5] Similar to the way people talk out about ‘life after death’, i.e. how do you know? Conveniently, nobody has ever come back to tell us. Ergo; you never have to validate your claims.

Image credit: Kiyose Nakae ‘Jiu Jitsu Complete’ 1958.

You’d better hope you never have to use it – Part 1.

An alternative view on self-defence and ‘effectiveness’. I have been thinking about this for a long time now. Every time I see this subject brought up on martial arts forums, I find myself shaking my head; where is the objective clarity? Where is the cold scalpel of logic which is needed to cut through the mythology, pointless tautology and hyperbole? In addition, why doesn’t someone call out those who are too quick to erect a whole forest of straw men; those who set up false equivalents and apply simple answers to complex questions?

Self-defence, what does it even mean?

Taken at face value it’s supposed to be our raison d’être, but we know that Japanese Budo has worked hard to raise itself above primitive pugilism, and the inclusion of firearms into the mix has brought in an element of semi-redundancy, particularly in certain societies around the world. But we still have the hope that we can take the ethical and moral high ground through the philosophies of Budo, which, in itself is not above hyperbole (try, ‘we fight so that we don’t have to fight’, I know what it means, but I suspect I am in a minority).

Real Violence.

We tell ourselves that we are training so that we can protect ourselves against physical attacks by unknown (or even known) aggressors who clearly mean us harm. Realistically, most people have fortunately never really experienced that (here in the UK, despite what the papers want to tell us, we live in quite a peaceful society [1]). Hence, what people do is carry around an image in their heads of what that violence may look like; but, based on what exactly? Mostly, I suspect it’s a mish-mash of choreographed movie violence and random CCTV footage on YouTube; it is highly unlikely it will be based on real experience.

What does real violence look like?

I don’t like doing this but unfortunately, I have to base my proposition on a degree of personal experience, mostly (but not exclusively) from my younger days.

A list of what real violence tends to be:

Random, irrational, devoid of humanity (and often bereft of conscience), chaotic, usually spontaneous, ugly, seldom prolonged (most likely, over in just a couple of seconds), all too often cowardly with any elements of restraint removed by the effects of alcohol or drugs. Not in the least bit glamorous and hardly anybody comes out of it as a hero, and certainly nobody calculates the consequences of their actions.

It is this last one I want to look at in a little more detail. (Here’s where ‘You’d better hope you never have to use it’ comes in). I’ll start with; if you make a decision to punch, kick or elbow someone in the head, you’d better be prepared to live with the consequences.

One thing that tales from news media can tell us quite graphically and accurately, is the results and the aftermath of a physical assault; whether it is initiated by the aggressor or the defender, it doesn’t matter, James Bond or Jason Bourne never have to give a thought to the ‘bad guys’ they ‘take out’ in a fist fight, and neither are we, as an audience, expected to; the plot just rolls on. But that is the fantasy.

Read this account of a 15-year-old boy attacking a man with the so-called ‘superman punch’ resulting in the man’s death https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jul/25/polish-man-arkadiusz-jozwik-killed-superman-punch-court-hears

Lives ruined, families traumatised and all for what?

Someone once pointed out to me that all those techniques that are most effective in so-called self-defence situations can result in life-changing injuries and will most likely cause you to end up in court.

Please don’t misunderstand me, I am not advocating passivity or a total abrogation of responsibility, just a balanced grown-up attitude as to whether one is prepared to go for the so-called ‘nuclear option’ or not [2].

Practice and Theory.

As regards teaching self-defence classes; there is a wonderful contradiction worth considering. Nobody in the history of martial arts has EVER argued that theory has value over practice, but maybe in terms of practical, realistic self defence it does?