karate

Hierarchies.

This is not about politics (though it may start out like that).

It used to be said that if a man is not a Socialist when he is seventeen then he has no heart, if he is still a Socialist when he is fifty he has no head. This does not mean that you are supposed to swerve from left to right as you mature, personally I don’t subscribe to the tribalism of ‘left’ and ‘right’ anymore, they are both two cheeks of the same backside.

Socialists abhor hierarchies, while at the same time feeling it is necessary to utilise them (contradiction?).

Humans by their very nature have a desire to set up hierarchies, even where they do not exist.

Imagine a man who could balance ping pong balls on his nose; would he be content to be the only person who could do that? I doubt it; instead he would present it as a challenge to other jugglers and balancers, who would, inevitably, be able to repeat the trick thus rendering his ‘achievement’ as mediocre. So he then manages to balance two balls on his nose, one on top of the other; seemingly impossible and sets himself up as King of the Ping Pong Ball Balancers! A hierarchy is created – out of nothing. I suppose a good question would be; would ping pong ball balancing put food on the table? There lies another discussion.

In all hierarchies there are winners and losers and people in between and there is supposed to be mobility; not like the old feudal pyramid, more like a ladder.

The people on top give you something to aspire to – unless you are hopelessly stuck on the bottom and then you either resign yourself to failure and give up, or you become a festering ball of resentment, which is not healthy.

These people on the very top are there for a reason. To briefly examine that, it might be worth making a quick reference to French and Raven’s six bases of power. This was formulated in 1959 by social psychologists John French and Bertram Raven.

- Base 1. Legitimate power (or inherited power) – the person in charge has the right to be there.

- Base 2. Reward – You are rewarded by letting that person assume the position.

- Base 3. Expert – That person is the most skilled, so they should be on top.

- Base 4. Referent – the person is seen as the most appealing option because of their worthiness.

- Base 5. Coercive – The fear of punishment keeps this person on top.

- Base 6. Informational – (added later and very apt to today) The person on top controls the information that people need to get stuff done.

Every boss I have ever met considers that ‘Base 3’ is why they are there, with a liberal dose of ‘Base 4’ of course.

Everything you have ever done and gained a feeling of positive achievement from existed within a hierarchy, and that of course includes martial arts training. If the hierarchy is working well you have confidence in the system because opportunities arise from engaging in it, you reap the rewards of your own efforts.

Ambitious people tend to form their own hierarchies and strive to become king of their own tiny little hill, and we see that in the martial arts all the time – everyone wants to King of the Ping Pong Ball Balancers.

Tim Shaw

Order and Chaos – Why it Matters for Martial Artists.

I have recently been reading Jordan B. Peterson’s ’12 Rules for Life’ and I have watched a few of his lectures online. Peterson is a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Toronto and has some quite interesting things to say. His views on Order and Chaos chimed with something that had been going through my head for a long time.

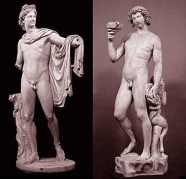

Way back when I was a university student I attended a lecture on ‘Apollo and Dionysus’ that got me thinking. As you may know Dionysus (Bacchus) was the god of wine, darkness and of wild hedonism and chaos, a real fun guy. While Apollo was the god of reason, order, light, a total bore; the ‘Captain America’ of superhero gods. The logic of this was creating models of duality; virtually the same as the Taoist Yin and Yang, which is a simple circular motif of two halves, one black, one white separated by a curving line.

For the purpose of explanation ‘Order’ and ‘Chaos’ are the most useful terms.

The realm of Order is everything we know; where rules are followed, structures are in place, it is comfort and to some degree also complacency (but more of that later). Whereas Chaos is unpredictability, it is the gaps between the laws that protect us; it is what happens when things break down, small scale and large scale, ultimately expressing complete anarchy.

I witnessed a minor version of chaos recently on a Tube train in London late at night. The majority of the passengers were abiding in the world of order, following social protocols, but a small noisy part of drunken people came into the carriage, not following the rules; nothing significant happened but to me they were like illogical, fuzzy minor condensed version of chaos, anything could have happened, the potential was there, just by the presence of chaos.

Peterson says that it is healthy to not just acknowledge chaos but also to engage with it. The complacency that comes with order ultimately would just result in you staying in your room. Progress comes from stepping out into the world and moving away from your comfort zone and putting yourself in more unpredictable positions (chaos).

Look at what we do in martial arts training.

In a very simplistic way we discipline ourselves through the most orderly, regimented environments imaginable, we convince ourselves we are training for chaos, and, in a way we are, but not necessarily in the way we think. Violence is an extreme embodiment of chaos and should not be taken lightly, but it is a complex issue full of wild variables. Just think of one of the worst scenarios; multiple attackers, unfamiliar environment, motivations unclear, limited light, all parties befuddled or fuelled by alcohol – it’s a mess. But this is an extreme.

Let’s go back into the Dojo; here are some examples of engaging with chaos that lead you towards more positive outcomes.

It starts out very simply, where you pressure-test your training in more manageable ways.

In a formal setting there is scope for tiptoeing into the chaos zone; e.g. if you work kihon gumite but the Torime doesn’t know what the second attack is; you could gamble, but it’s better to see if you can resolve the problem through your conditioned training.

Every time you take part in sparring; there are rules but essentially you are engaging with controlled chaos.

In my Dojo we have been working for a long time now on devising new ways of pressure-testing our reactions to attacks, creating opportunities to really work our conditioned responses, one method we use is called Ohyo Henka Dousa, a method of continual engagement with an attacker’s intent.

To go back to the Yin Yang symbol, Peterson says that the curving line between the two areas is a line that we should tiptoe along, occasionally deliberately allowing our foot to stray into the zone of chaos and very much acknowledging that it is part of our lives – something that can be used for good.

Tim Shaw

Waza o Nusumu.

‘Waza o Nusumu’ is a phrase I’d heard and read about some time ago; essentially it means ‘stealing technique’. It relates to an old style aspect of direct transmission of knowledge from Sensei to student. We know that verbal transmission or just telling students how techniques and principles work is not an efficient method of passing high levels of skill and knowledge on to future generations. We also know there are other models; for example in old style Budo teachers passed information to their students by having them ‘feel’ their technique, but even that is a flawed method. How do we know if the student is really getting to the core of the technique, or is just mimicking the exterior feel of what they thought was going on?

Waza o Nusumu sounds subversive or even dishonest, but really the teacher is in cahoots with the student; he wants to present the technique to the student, perhaps in an oblique way, a hint here, a hint there, or even a quick demonstration to see if they have the ability to grasp it.

I am reminded of a Wado Sensei I know who wanted to explain Okuriashi foot movement to a junior student and so had a £5 note on the floor with a piece of cotton attached and told him if he could put his foot on it he could have it; every time the student tried to put his foot on it (with Okuriashi movement) the note was snatched away.

It also makes me think of Fagin in the musical ‘Oliver’, the scene where he encourages Oliver to steal the handkerchief dangling out of his pocket.

Image credit Columbia Pictures.

As mentioned earlier, all of this can fall apart if the student only grasps a part of the picture. It is entirely possible for the student to make the assumption that they’ve ‘got it’ when they haven’t, probably because they’ve projected an understanding on to it that is immature or underdeveloped; this is where the importance of ‘emptying your cup’ comes in.

Another side of this is that the student has really work at it to decode what they have ‘stolen’. There is significant value in this; partially because understanding with your head only is never enough, this is part of making the technique or principle your own. If you are to truly value it and ‘own’ it it has to come from your own sweat.

Tim Shaw

Feedback (part 2).

What information is your body giving you? Are you truly your own best critic?

When we are desperately trying to improve our technique we tend to rely on instruction and then practice augmented by helpful feedback, usually from our Sensei.

But perhaps there are other ways to gain even better quality feedback and perhaps ‘feedback’ is not as simple as it first appears.

If we were to just look at it from the area of kata performance; if you are fortunate enough to have mirrors in your training space (as we do at Shikukai Chelmsford) then reviewing your technique in a mirror can be really helpful. But there are some down sides. One is that I am certain when we use the mirror we do a lot of self-editing, we choose to see what we want to see; viewpoint angle etc.

The other down-side is that we externalise the kata, instead of internalising it. When referring to a mirror we are projecting ourselves and observing the projection; this creates a tiny but significant reality gap. It is possible that in reviewing the information we get from the mirror we get useful information about our external form (our ability to make shapes, or our speed – or lack of speed.) but we lose sight of our internal connections, such as our lines of tension, connectivity and relays. We shift our focus away from the inner feel of what we are doing at the expense of a particular kind of visual aesthetic.

You can test this for yourself: take a small section of a kata, perform the section once normally (observe yourself in a mirror if you like) then do the same section with your eyes closed. If you are in tune with your body you will find the difference quite shocking.

Another product of this ‘externalising’ in kata worth examining is how easy it is to rely on visual external cues to keep you on track throughout the performance; usually this is about orientation. I will give an example from Pinan Nidan: if I tell myself that near the beginning of the kata is a run of three Jodan Nagashi Uke and near the end a similar run of three techniques but this time Junzuki AND that on the first run of three I am always going towards the Kamidana, but on the second run of three I will be heading in the direction of the Dojo door, I come to rely almost entirely on these landmarks for orientation, thus I have gone too deeply into externalising my kata; it happens in a landscape instead of in my body. Where this can seriously mess you up is if you have to perform in a high pressure environment (e.g. contest, grading or demonstration) your familiar ‘landscape’ that you relied heavily upon has disappeared, only to be replaced by a very different, often much harsher landscape, one frequently inhabited by a much more critical audience. A partial antidote to this is to always try and face different directions in your home Dojo; but really this is just a sticking plaster.

Another quirky odd anomaly I have discovered when working in a Dojo with mirrors is that during sparring I sometimes find myself using the mirror to gain an almost split-screen stereoscopic view of what my opponent is up to, tiny visual clues coming from a different viewpoint, but it’s dangerous splitting your attention like that and on more than one occasion I have been caught out, so much so that I now try and stay with my back to the mirror when fighting.

Another visual feedback method is video. This can be helpful in kata and individual kihon. In kihon try filming two students side by side to compare their technical differences or similarities. If you have the set-up you could film techniques from above (flaws in Nagashizuki show up particularly well).

There are some subtle and profound issues surrounding this idea of ‘internalising’ ‘externalising’, some of it to do with the origin of movement and the direction (and state) of the mind, but short blog posts like this are perhaps not the place for exploring these issues – the real place for exploring them is in your body.

Tim Shaw

Feedback (Part 1).

It’s very obvious that people always appreciate having the opportunity to offer their opinion; particularly when it is something they really care about. So with that in mind I decided to consult with our regular students at Shikukai Chelmsford through the medium of a questionnaire.

I must admit, I was curious as to how this can be done through new technology. So initially I not only set about designing my questions but also researching the available platforms.

I had heard about Survey Monkey and assumed that this was going to be the one to use, however, after signing up and learning about all the whistles and bells and putting my questions in to the template I hit a major hurdle at question 10…. Something that wasn’t clear from the outset; i.e. that this so-called ‘free’ service was only free if you didn’t go beyond 10 questions, after that they wanted £35 a month, (sneaky eh!). So, frustrated and ever so slightly miffed I had to abandon the smiley happy world of Survey Monkey.

More research lead me towards Google Forms, this was totally free and in lots of ways was even better than Survey Monkey.

The idea of a questionnaire has many advantages, particularly when it is anonymous (I made sure that this was the case as it would allow people to give candid and honest responses). Without wanting to use too much jargon I would also say that Dojo members are also stakeholders; it’s in everyone’s interest that all needs are being addressed; in a successful Dojo the whole is far greater than the sum of its parts.

I think we are very fortunate at Shikukai Chelmsford that the social make-up and personalities all mesh neatly together, largely because we have a common goal and it is in our interests to perpetuate that particular dynamic – although I must say that this is the same for Shikukai as an organisation across all Dojos. However it does not mean that we have everything right; so the best thing is to consult the members.

The range of questions went from organisational issues; times, number of sessions, costs, etc, to venue and facilities; then on to training content, and even looking at fairness and equality. The links to the questionnaires came through to members via email and through Facebook, which was very slick. I must say, the design template also looked incredibly neat and professional. The results came in steadily and were really helpful in getting a snapshot of where we currently are. The culmination of all this is that I will share the results with the students and this in itself will promote more dialogue and then work with them to address any issues.

Brilliant!

Tim Shaw

Sticking Points.

More technical stuff.

Because you have to start somewhere, all of us use form as a framework to hang our stuff on. By form I mean, end position, making a shape, a posture, an attitude usually based around a stance, that kind of thing. This becomes our go-to teaching/learning aid. My argument is that we fixate far too much on that aspect of our training. Yes, it’s really important and can’t be by-passed, but to some it becomes an end in itself. It becomes a crucial moment of fixation working a bit like the full stop at the end of a sentence. Of course this is reinforced by a picture book mentality; where that end posture is used to judge quality, as you used to find in karate books that show kata, kihon or kumite. I have written before about the idea that some people think that the posture alone is enough to judge how good a person’s technique is – well, usually that and how much ‘bang’ they can give it. I find this really difficult to accept; surely we have moved on from this rather low branch in our evolutionary development?

Fixation points can be very dangerous; and habitually programming them into your nervous system is not what you should be doing as a martial artist. When the mind becomes fixated energy and intention stagnate and become momentarily stuck.

Don’t confuse this with pauses – I know this may sound counter-intuitive, but ‘pauses’ can be used as part of the necessity to manipulate the tempo and rhythm of an encounter, e.g. to create a vacuum to allow your opponent to fall into (another blog post perhaps).

Look for things that ‘happen’ on the way to something else. By that I mean; for example, watch an expert in motion and try and identify when the engagement first happens. If it’s of a high quality it will cause an effect on the other party; it may even cause his mind to fixate; a crude example would be an initial shin kick, or a distracting inner sweep; but it may well be something much more subtle and it won’t always happen on initial contact.

I can think of some very interesting manoeuvres in Wado where the atemi-waza occurs seemingly between moves. By this I mean, many of us too easily buy into the idea that a technique (be it hit or block) happens at the moment your ‘stance’ arrives; it doesn’t have to be this way. There is a time-line between moves, and that time-line has opportunities that relate to how your body is positioned in relationship to your opponent; it might be angle, it might be distance, or a combination of both, but you have an opportunity to do your stuff while on your way to your primary objective. All of this is the opposite of ‘fixation’. A mind frozen or fixated on a block or strike dies at that point; the engine has stalled and there’s nothing left but to throw away crucial time, slip into neutral and turn the ignition key again.

During sparring try and take a tally of how many times opportunities occurred and yet you were unable to capitalise on them. Often this reveals a number of weaknesses; one example being an overreaction to the threat of your opponent’s technique, but another is when you become fixated on what you are going to do, or have just done. Against a poor opponent you will get away with it, but against someone good your frozen nano-second will supply an excellent window of opportunity for your opponent.

And there’s another thing; don’t wait for the opponent to supply you with the big window of opportunity, slot into the smaller windows; be like a key in a lock.

Tim Shaw

The Dunning Kruger Effect.

“When incompetent people are too incompetent to realise they are incompetent”, is only part of the story of the Dunning Kruger Effect. There is a lesson here for all martial artists (as well as anyone involved in any areas of the development of skill/knowledge).

The Dunning Kruger Effect is a graph or timeline explaining our perception of our own competence.

The Effect was first described in 2000 by David Dunning and Justin Kruger of Cornell University. At the extreme left of the graph is a statistical pinnacle, this describes the supreme level of confidence that a person with very little skill tends to have. The timeline then turns into a cliff face and as the true nature of the specific skill reveals itself and the level of confidence plummets. Then comes a long pit of despair; followed by a gentle rise towards a modest level of confidence.

I wouldn’t presume to ask anyone to try and locate their own position on the Dunning Kruger graph line; that would be a wonderfully ironic contradiction, particularly if they are near the beginning of the graph line. As martial artists given enough time we may be able to look over our shoulder at our younger selves and remember our own ‘cliff face’ moment, but all I would say is, be thankful for it, and be thankful that you had enough fortitude to soldier on.

I am not naïve enough to think that the Dunning Kruger Effect is liable to be as neat a curve as the diagram suggests; but taken in general it is liable to follow that path.

But what about the ‘modest level of confidence’ at the end of the graph line? This is another part of the story; Dunning and Kruger also revealed that when people do develop their skills to a high level they are also inclined to score low in confidence, because they believe that those around them may also possess similar skills. This stands to reason in some ways because if your world is populated by people of a similar advanced technical background then you are likely to be only making comparisons with people like yourself.

The ‘modest level of confidence’ may sound like taking a position of being overly modest or humble but it also may be a symptom of what is known as Imposter Syndrome. Although not classified as a mental disorder ‘Imposter Syndrome’ is a frame of mind whereby a person feels that their success is fraudulent, or that they’ve just been lucky. An author once said, “I have written eleven books, but each time I think ‘Uh oh, they are going to find out now; I’ve run a game on everyone and they are going to find me out’”, the author was Maya Angelou.

There is a basic checklist for Impostor Syndrome; it is;

- If you exhibit signs of being a perfectionist.

- If you find yourself overworking.

- If you have a tendency to undermine your own achievements.

- If you have an unreasonable fear of failure.

- If you are inclined to discount any praise you receive from others.

I suppose for senior martial artists there is another negative tendency, best summed up by a T-Shirt slogan I once saw for elderly bikers, “The older I get, the faster I was”. For martial artists one of the symptoms of this unacknowledged condition is the illusion that your belt is weirdly getting shorter day by day!

Tim Shaw

Cultural Appropriation.

Recently there has been a significant amount of media chatter about ‘Cultural Appropriation’.

Susan Scafidi defines the negative aspect of cultural appropriation as, “Taking intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone else’s culture without permission. This can include unauthorized use of another culture’s dance, dress, music, language, folklore, cuisine, traditional medicine, religious symbols, etc. It’s most likely to be harmful when the source community is a minority group that has been oppressed or exploited in other ways or when the object of appropriation is particularly sensitive, e.g. sacred objects.”

It’s interesting to look at how might be applied to Western-based Budoka. Firstly I’m not so sure that the standard bearers for traditional Budo inside Japan worry too much about having their cultural practices and icons ‘appropriated’ by enthusiastic Westerners. Robert Twigger in his 1997 book ‘Angry White Pyjamas’ said in a specific and telling quote, “Sara thought martial arts were pretty silly. To a trendy young Japanese, aikido was about as sexy as Morris Dancing”. I suppose that the more archaic and, dare I say it, ‘traditional’ a Japanese martial arts the westerners tries to immerse themselves into the more bizarre it must look to the outsider.

A friend of mine is a long established practitioner of Kyudo; a while ago he invited me to his Dojo. I must have looked upon it as creature landing from another planet; even though I desperately sought common ground I struggled to relate to the ritual and obsession around what in actual fact was a martial art that was based around just one simple action; firing an arrow at a target. Of course I realise there was far more to it than that, and he was able to explain to me the cultural significance and deeply personal struggle that all serious practitioners have to come to terms with. But the ritual observances and the setting up of the Shinto shrine, all of which seemed to take up half of the session, left me wondering exactly what was going on? Was I perhaps witnessing a more exotic version of what the Sealed Knot get up to every major summer Bank holiday? Or was this something else?

The opening quote hinted at an ownership issue; I get that, and I also understand that in the hands of the truly ignorant cultural icons can be misunderstood, misrepresented or even abused. They may even evolve into ‘Cargo Cults’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cargo_cult ). I’m pretty sure this happens in the martial arts, it’s all over YouTube, but I think most people can see that and just find it a bit….sad. But hey.

But here’s a thing. Let me explain this through the lens of Japanese Art, just to show that Cultural Appropriation is not a one way street.

Pre the arrival of western cultural artifacts to Japan the Japanese printmakers and painters had no concern with western ideas of space and depth in visual compositions. I have at home an original woodblock print by Japanese artist Tachibana Morikuni (1679 – 1748) of an Ox under willows, there is only the vaguest nod towards anything that might relate to foreground, background or middle distance; it’s all based upon a very formulaic and decorative methodology. When the later artists were exposed to western art the game changed, Hiroshige, Hokusai etc. embraced the ideas of perspective and distance and in Hokusai’s case he created visual puns, e.g the swamping of the mighty Fuji by the great wave!

But, when Japanese artifacts arrived in Paris wrapped in throw-away Japanese prints, Post-Impressionists became fascinated by the visual conceits and ‘appropriated’ their methods for themselves – oh the irony!

‘Oxen’ by Tachibana Morikuni (1679 – 1748)

Tim Shaw

Body Maintenance, Body Development.

Let me start by saying that I am in no way an expert in this area and I hold no recognisable qualifications; but I wanted to put a few thoughts together about body maintenance based upon my forty-three years of experimentation, failure and accumulated damage; some of it self-inflicted. (I started my Wado training in 1974).

I say that, but in actual fact I think I have been quite lucky; I have never broken a major bone and to my recollection I have only ever been knocked out once. In my early training I did some really stupid things, practices that are now considered Neanderthal and downright counterproductive; but you can almost get away with it when you have youth on your side. In your teens and twenties you believe you are indestructible and the Mantra, ‘That which does not kill me makes me stronger’, borrowed from Nietzsche, becomes an excuse for all kinds of damaging activities. In a macho society you all support each other in the delusion that if everyone is doing it then it must be right, and so ballistic stretching, repeatedly allowing yourself to be hit, throwing yourself straight into extreme exercises with no real preparation or warm-up all seem like the right thing to do.

They say that hindsight is always 20/20 but really; what were we thinking?

Thank goodness we are now all better informed. Developments in science, as well as information available on the Internet has resulted in us all being more knowledgeable. But even that doesn’t tell the full story. We are not all the same; our bodies don’t roll off a production line. We inherit our physical capabilities and limitations from our genes and in later life we carry around the burdens created by lifestyle, accident, illness and environment.

I spent some time under the care of a very experienced physiotherapist who was helping me solve a particular joint problem. I always enjoyed treatment from him because of his blunt and frank explanations of how the body works and tales of the stupid things people do; it was worth every penny. I would advise anyone suffering with injury to seek out a really experienced physio; as someone once pointed out; you wouldn’t think twice doling out £300 to have your car fixed, what price do you put on your own body? The physio opened up a whole new world to me regarding the subtleties of the physical mechanism; how easily things can get out of whack and how resilient the body is; but it was the methods used to treat the injuries and imbalances that intrigued me the most; some of it coming out of a need to address engrained habits and the way the body, out of expediency, bodges its way through things.

Without turning this small article into a heavyweight study I want to boil everything down to a few basic pointers:

- Be informed and realistic about what your body can do (one size does not fit all) there’s no excuse for ignorance.

- Work your body in a way that it supports what you want to do with it. Don’t assume that everything you need for physical conditioning will happen in the Dojo alone. I learned this lesson from the late Suzuki Sensei. When I moved to the south of England and was able to train with him regularly I was initially surprised that we never did any warm-up exercises prior to the senior classes. We used to warm-up in any available space outside beforehand. Suzuki Sensei’s approach was that you are here to do karate not calisthenics.

- Remember, there is development and maintenance. As you get older maintenance becomes more important in that you need to maintain flexibility and core strength, particularly when muscle strength begins to decline; but if you aim for development then maintenance becomes a given.

- Be honest in identifying your body’s weaknesses, but also your limitations. For example; if you start your karate training later in life a jodan kick may not be possible for you outside of radical surgery, but really that doesn’t matter, mawashigeri jodan is one of many techniques used to solve a problem, and in reality it is unlikely to be the technique that gets you out of trouble.

- Don’t undervalue what you can’t see. By that I mean the benefits of body movement based upon training methods like yoga or Pilates cannot be overstated; but the external advantages are difficult to see. Internal structure and work on complementary muscles and tendons which support movement such as those found in yoga and Pilates are really valuable to martial artists.

- One last word of warning; the body is affected by the state of your mind. The mistake we make in the west is to split the body and the mind. If your mind is in the wrong place, or your thoughts, value and judgements are askew then this will wreak revenge on your body; maybe not at the beginning but certainly further down the line there are more possibilities of the wheels coming off.

Tim Shaw

Mikiri.

I thought it was time to write something technical, though normally I am loath to do so as I get frustrated with people who ‘learn’ from the Internet, and I have recently had to deal with unscrupulous individuals plagiarising my past articles (this is why I haven’t published any lengthy articles in a long time).

But here goes anyway.

In my attempts to work with my own students on sharpening their paired kumite and develop a real edge to their practice I recently listed a whole catalogue of aspects and concepts that must be ticked off if students are to get under the skin of what is going on. Inevitably some of these concepts are interconnected; this was where the idea of Mikiri came in.

Mikiri is basically the ability to judge distance by eye and act accordingly. Naturally this is linked to timing as well. In Wado paired kumite the ability to perfectly judge the danger distance, or the potential and reach of an opponent’s technique is vital. But all of this may have to be calculated in a split second. In Wado and other Japanese Budo you can see references to this quite frequently and it becomes more critical if weapons are involved; this means that calculating for one distance (kicking of punching range) is far too limiting; for example, an eight inch blade gives the opponent an eight inch reach advantage.

But this is only a part of what I want to discuss.

We are actually amazingly well-equipped already; we actually do this stuff naturally. Picture a moment from everyday life when we have had to drive an unfamiliar vehicle; something much larger than we are used to. Imagine if you have to manoeuvre the vehicle down a narrow street with parked cars both sides, and, amazingly you succeed; a calculation just based upon a mere glance at your wing mirrors and the distance they occupy. Or even just walking or running. When running you instantly calculate the half second before your heel hits the ground and then all your muscles coordinate beautifully and propel you on to the next stride; and this happens hundreds if not thousands of times! You only really notice it when something goes wrong, e.g. on rough ground where you miss that pothole sneakily hidden behind a clump of grass and then the landing is jarring and the muscles have to go into emergency mode to stop you going head over heels.

But, what is interesting is that when you have to deal with a punch or a kick this well-coordinated judgement eludes you. The reality is that your mind becomes the real enemy; you become overly cautious, fearful of the intent of your opponent and often we just over-compensate.

A conversation with a Japanese friend who has a background in swordsmanship informed me that this same concept is an important part of engaging with the traditional Japanese bladed weapons.

But it’s no use just acknowledging the concept; it’s what you do with it that counts. In training there are multiple opportunities to practice it; not just the formal kumite but also within free sparring; observe how close or far away you are when dealing with a committed attack. Congratulate yourself if the attack misses you by a whisker, or scrapes your skin; but be aware, that is only the prelude…. The opponent has given you a window of opportunity; if you don’t condition yourself to take it the concept becomes redundant and meaningless.

This takes an awful lot of training.

Tim Shaw

Shugyo.

There are lots of Japanese terms relating to martial arts that in the West have become either talismanic or even fetishised. I am certain that there people out there who are non-Japanese speakers who may even collect these terms and phrases.

For me, they are interesting because when you examine them and try to get a handle on what is going on you really have to figure out how they fit into the whole of Japanese culture both historical and present, and that is a challenge in itself.

One phrase that cropped up recently in a conversation over beer (as most of these types of conversations seem to be recently), was ‘Shugyo’.

I remembered an explanation by Iwasaki Sensei about three types of training; ‘Keiko’, ‘Renshu’ and ‘Shugyo’. Keiko was explained as just hard physical training, it could include all the supplementary stuff like strengthening, conditioning, etc. Renshu was like drilling, refining, engaging with the technical aspects. Whereas Shugyo was a period of total emersion, some say ‘austere training’. Sensei explained that to engage in Shugyo you had to imagine some kind of martial arts monk, someone who has nothing in his life apart from mastering his art. At the time the idea seemed appealing; particularly the bit about turning your back on the world.

But there are other ways to think about Shugyo. Does it really have to involve a split away from society? I don’t buy the idea of meditating half way up a mountain, except perhaps on pragmatic grounds (where else can you find peace and quiet?). I am also sceptical about the Taoist monk retreating from the world. I’m more for the Neo-Confucian idea that practice and enlightenment can be found in the marketplace and the hurly-burly of city living.

I am coming round to the idea that Shugyo isn’t perhaps some all-defining experience; a one-off commitment like a pilgrimage. And the idea that you are guaranteed to come out the other side enlightened and cleansed with mastery at your fingertips is perhaps a little too romantic and creates fodder for the fantasists. It also seems to leave no room for one of the rude facts of life….failure.

Perhaps Shugyo is more episodic. It is possible that some people have engaged in Shugyo without even knowing it? Maybe those times of intensity were just seen as ‘rites of passage’ but in reality ticked all of the ‘Shugyo’ boxes. Admittedly they weren’t self-directed, but those grinding relentless repetitions were focussed, unforgiving and as near a perfect hot-house as you were ever going to get. I am thinking particularly of those long, long hours on whatever course or camp it might have been. But here’s the question I have been asking myself; if those were episodic ‘Shugyo’ opportunities were they well-spent? Or did they happen at the wrong time in our development; or beyond that, did we have the right material to work with?

From a personal viewpoint; with the right material, the right direction and the right background, the best time is…now.

Tim Shaw

10,000 hours.

It has often been said that to an ‘expert’ in absolutely anything you need to have accumulated 10,000 hours of practice.

I am sure that in our search for quick answers and ‘sum it all up in one soundbite’ style solutions many people will focus on this factoid and be instantly comforted by the convenience of this as a theory.

But, unfortunately, like a lot of simple answers this idea supplies a generalised truth but fails to describe the whole story.

Scientists and statisticians have drilled down into this idea and have found it to be wanting.

I must admit to have been seduced by this formula, and even busied myself trying to work out how many hours a day I would need to train in Wado Ryu karate to reach ‘expert’ level. By the way it works out as about 4 hours a day over about 10 years.

This is far far too simplistic. The experts looked at chess masters and classical musicians; a good choice if you want mental capacity and high levels of manual dexterity; I would worry about the levels of physicality required for martial artists, after all, certain types of athleticism have very limited shelf-life.

But, time in service alone did not cut it. The experts found that with chess masters there were examples where it took one expert 26 years to reach a high level of mastery, while another ‘expert’ achieved the same level in two years. Statistics like this make a mockery of the ‘10000 hours’ theory.

So, what’s going on? There is of course the wildcard of ‘innate ability’, but that alone is not a prerequisite for success. I have witnessed individuals of innate ability who reach a glass ceiling and are so cock-sure of their own ability that when they reach a high level of success that they become drunk upon their own perceptions of their ability that they are then unable to empty their cup and move beyond this level – effectively they become unteachable.

There are of course those who are doomed to make the same mistakes over and over again – martial arts ‘Groundhog Day’. Those who claim to have twenty years of martial arts experience yet actually have one year of martial arts experience twenty times!

Personally, I would posit that the way to success is to maintain an active curiosity and a secure work ethic, tempered by correct guidance and a clear direction. Keep your cup empty.

Tim Shaw

Tangible and Intangible.

I’m going to try to describe my perception of something that is really quite difficult to pin down. This is just my opinion, but it is based upon things I have seen and experienced at one level or another.

When something is ‘tangible’ it is observable from the outside; when it is ‘intangible’ it is often hidden or difficult to perceive. The tangible could be described as the exterior; while the intangible is the interior. Often we think we understand something based upon what we see is happening on the outside but the real truth of the matter is what is going on in the inside. Or we base our judgements upon prior experience and run the risk of misunderstanding what is really going on – like the story of the blind men and the elephant (Link).

When we are looking at the martial arts, specifically Budo traditions we are observing and experiencing something that is often difficult to grasp.

According to Japanese karate master Ushiro Kenji in his book ‘Karate and Ki’; Japanese arts fall into two categories; those that have an obvious outcome, an end product that is a quantifiable commodity, like the craftsmanship of a Japanese carpenter or a visual artist, swordsmith or potter. And those traditions that have no material outcome, like the Budo master or the traditional Japanese flute player; they are just as valuable but their end products are impossible to lay your hands upon, to weigh and measure, they are more ethereal, their true value is found in the intangible. Often they are part of a living tradition, one that has developed over time, but only survives through the physical human frame.

This ‘physical human frame’ is the instrument, not the finished artefact; there is no actual material artefact. So the martial artist’s body is like a musical instrument, superbly crafted in itself but it’s the output, the workings of the instrument where the real value lies.

The instrument is merely the vehicle for the music. As an example; recent studies on the prestigious violins made in the 18th century by Antonio Stradivarius reveal that there is no real difference between the Stradivarius and a well-made modern violin. Blindfold experts could not tell the difference and even favoured the modern instrument over the Stradivarius. This just goes to prove that we have to be wary of mythologies that accumulate over time.

What is also interesting is that these very rare and expensive violins are given out to world famous musicians who are considered as temporary custodians, this is an acknowledgement of the fleeting, intangible nature of music at the highest level; what is produced cannot be held in your hands, so it is with the highest levels of Budo. The exterior appearance can be caught on film, but the real value is in the intangible. Trust your feelings not your eyes.

Tim Shaw

Operating System Update.

As an instructor (and a student) one thing I feeling strongly about is that I should be in a state of constant learning.

In the teaching profession they rightly make a point that all teachers should be setting themselves up as what they call ‘Life Long Learners’, as an example to all of the young people in their charge. It’s the same in karate.

Wouldn’t it be a shame if instructors rested on their laurels and past triumphs and conducted themselves as if they had topped out on all they can learn?

Some seniors seem to tacitly acknowledge that their cup is not full and seek to top up from other sources, without realising that the well-source of Wado has not run dry and that what we see is just the tip of an iceberg.

Recently I found my Wado boundaries being stretched by my Sensei who laid upon me yet more concepts and practical interpretations, and, while searching for an appropriate metaphor, I hit upon the idea that I had been subjected to yet another ‘operating systems update’. This useful piece of jargon from computer science seems to fit neatly with what should be happening to all of us.

Of course this metaphor can be extended, and it’s only when you meet up with other operating systems that are still running the equivalent of Windows 8 that you realise how valuable these ‘updates’ are. It’s not uncommon to actually meet someone still operating on the equivalent to a 1982 Commodore DOS and in such cases the two systems will find it virtually impossible to communicate, short of a rebuild.

Apple and Microsoft both pressure test their latest updates by releasing them before they are fully functioning and that is when they find the bugs and glitches that they can then fix with other minor updates (well, that’s how I see it anyway). This also fits neatly with what happens to me while working with my Wado updates; my body is still working things out on the hoof.

But the up side is that if you are following Wado Logic then the adjustments should eventually click in; either that or Sensei comes along and tweaks your system.

Tim Shaw

Composure.

I am sure he won’t mind me saying this but Shikukai chief instructor Sugasawa Sensei always impresses me with his appetite for embracing words and concepts that exist in the English language. He is always searching for the most apt linguistic model to try and cross cultural and language barriers. Once he latches on to a new word, analogy or aphorism he exploits it with great energy.

One such word cropped up a little while ago.

On an instructors course Sensei used the word ‘composure’; I won’t go into detail about the context in which Sensei used this word; but it had me thinking more about what it means for us and how it is applied.

‘Having an air of composure’, i.e. what the attributes of composure communicate to others. This is without a doubt a useful and positive persona to project, especially for martial artists. But it has to be real; it should not be faked or put on and taken off like your Keikogi jacket.

Projecting composure should be a natural by-product of a balanced mind; something we should all aspire towards; easy to talk about but difficult to achieve. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t aim to become more balanced and more composed, but identifying the times when we are cool and composed; (or the reverse, flustered, angry or allowing situations or people to overcome you), are good places to start.

In Oriental philosophy Neo-Confucianists like the Japanese scholar Kaibara Ekken (1630-1714) encouraged self-examination, monitoring your behaviour and ‘renewing yourself each day’. He also said that you should listen to trusted and reliable friends and allow them to point out your errors. Expanding on this he says it is like the game of Go where the outsider/onlooker can often see the right move before the players can.

Returning to the ‘air of composure’. Your mental attitude projects outwards and is easily picked up by others. As humans we are very good at this and are sensitive to even the most subtle forms of non-verbal communication; look how we ‘mirror’ other people’s gestures subconsciously, to let them know that we are on their wavelength. A steady gaze, relaxed and alert posture, confident, (but crucially, non-aggressive) give clues and act as hints and messages to others. The reverse is also true: shifty downcast eyes, tensed shoulders are all negative messages; as are aggressive looks, pushed out chest, agitated behaviour, all red flags to others in the vicinity.

New Age philosopher and guru Eckhart Tolle in his description of what he calls the ‘pain body’ describes the burdens people carry around with them, of past anger, anxiety and pain; on to which they willfully heap new anxieties, pain, anger, creating a destructive cocktail which often has further unhappy endings.

But he also says that negative angry people act as a magnet to other negative angry people. They spot each other across a crowded floor and are drawn to each other like preening cockatoos who attack their own reflections in a mirror.

Or another example is how angry negative people are pulled into relationships with other angry negative people; their life dramas mirror each other and their destructive flashpoints cause chaos which affects all around them, but is particularly damaging for themselves. Wrapped up in their own back-story they can’t see the wood for the trees.

Composed people are a much more attractive option. They are the people you can rely upon in a crisis, they are cool, unflappable and confident; but, hopefully, they are not just a machine, they also have a beating heart. Something every martial artist should aspire to.

Tim Shaw

Apocrypha.

“Apocrypha: A story or statement of doubtful authenticity, although widely circulated as being true.”

The truth is that the martial arts abound with Apocrypha, but I don’t think that this is a bad thing, as long as they are all taken with a huge pinch of salt.

My approach to some of the apocryphal stories about the martial arts is that I look for the kernel of truth within the myth. Not from the view that there must be tiny element of veracity lurking underneath the embellishments of stories told and re-told hundreds of times; but instead I look for the lesson or moral behind the survival of such a story – it could perhaps contain a greater truth than the fairy-tale pretends to.

Here are two of my favourites that serve to explain my thinking.

Someone told me a story about tourists being shown around a famous Chinese Temple associated with martial arts. On arriving at a particular courtyard the guide pointed out regular hollows worn into the brick paving. The tourists were told that these hollows were the result of martial arts monks spending hour upon hour in horse stance practicing their moves. However, the observant tourist might also notice that the hollows may also have been the result of weak spots in overhead roof drainage where rainwater had dripped over hundreds of years. Naturally the guide chose to ignore this very practical explanation; thus the myth lives on. Should we therefore scoff at this deliberate hokum? I don’t think so. The factual account might be wrong but the essence of the story contains another truth; more like a model, an idea, a concept. It conjures up a heightened and exaggerated admonishment endorsing the fruits of disciplined and prolonged practice, and, to my mind that makes it useful.

Another example concerns a story about one of members of the Yang family of late 19th century Tai Chi fame. It was said that if a bird was to land on master Yang’s outstretched index finger, the bird would find itself unable to fly away unless the master permitted it to do so. The explanation for this was that the master was so highly tuned to pressure sensitivity that when the bird tried to use its legs to launch the master would detect this and very subtly deny the bird a platform necessary to spring forth. Is this actually possible? Would a specialist in avian anatomy and the physiology of flight be able to tell us that this story is complete bunkum, because a small bird does not actually need to launch with its feet? I don’t know, and frankly I don’t care. The concept of heightened sensitivity is vital to practitioners of all martial arts (or at least should be) therefore to cook up such a seemingly tall tale serves as an aspirational template; albeit an apparently impossible one.

There are other stories where the essence surpasses the truth. There is something about the martial arts that promotes the telling of tall tales. Obviously some of these are there for political reasons; the mythologies live on long after people have passed away. I have seen recent examples where a certain level of gloss has been applied to boost the reputations of the living and the dead. Tales retold have an inevitable life of their own.

Tim Shaw

‘Never give a sword to a man who can’t dance’.

I’ve known this quote in various forms over the years, including ‘A man that can’t dance has no business fighting’.

Nobody seems to know exactly where this comes from; some say Confucius, others say it’s an old Celtic proverb. And even more disagreements occur over what it actually means. Some equate dancing with community, fraternity, even love and happiness, to counterbalance against the cult of the sword and the necessity for violence. I believe that you can make of it what you want.

I originally took it mean the skills needed to be a successful dancer have a similarity to the skills needed to be a successful fighter. Coordination being paramount; but also reading the rhythm and tempo of what you are reacting to. Taking the bigger picture it could be said that you read and react to elements of the physical world outside of yourself; so you perceive and measure the mood and intention of external forces and respond in a balanced way.

But it is interesting to stretch this comparison with the dancer even further. Take it from the point of a pair of dancers, imagine ballroom or passionate Tango. At first glance the connection between the pair is about cooperation, they work in a collaborative manner; they mesh perfectly and display their grace and fluidity effortlessly. Making a comparison with fighters this seems like a complete contradiction; two people who engage in combat don’t act like dancers, they try their utmost to baffle and confuse the opponent, they try to ‘wrong foot’ their attacker and fighters try hard to not get caught ‘flat footed’.

But perhaps that’s a little too narrow.

For example; there is rhythm in fighting. In free engagement you can dictate a rhythm for your opponent to unconsciously follow, draw him in, lull him into an expected pattern and then…break it. An opponent can be led by a shift in angle or stance or deceived by a posture or attitude. In Wado this can be done in free fighting and features in the more subtle elements of some of the paired kumite. In some of the more overt Jujutsu based paired kata Uke is forced into a response that is drawn out of him by Tori who leads him towards his own destruction. So there is an interplay going on. The usually accepted understanding of Uke as one ‘who receives’ is far too simplistic. Uke is not the stooge, fall guy or goon of Tori, there is two-way traffic going on here; this is an interplay of forces and intentions.

It’s a big subject, but…

Just to throw more mischief into the discussion, here is a quotation to leave you pondering. Nietzsche said, “I say unto you: one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star”.

Shimmy or sashay around that one!

Tim Shaw

Be wary of simple answers to complex questions.

With the internet there are so many ways to put your opinions out to the world and the problem is that when people are given the platform to state their views they will seldom have the courage to change those views should some new piece of knowledge come to light that challenges them.

If you do find that something you’ve stated as a fact turns out to be untrue, what do you do? Stubbornly hold on to your theory clinging on desperately to any piece of scant evidence that will support that view? Or do you crawl into a hole never to venture out into the world of opinions again? Or, do you re-evaluate, take stock, admit you were wrong and re-calibrate your views? I hope that all of us are big enough to do the latter. A quote attributed to Mohammed Ali is that “If a man looks at the world when he is 50 the same way he looked at it when he was 20 and it hasn’t changed, then be has wasted 30 years of his life” .

So it is with views about martial arts. I would say that people often carry on doing the martial arts for different reasons than the ones they started. For some people it starts with lack of confidence or even fear, for others it’s the buzz you get from the physical exercise. But carry on long enough and these issues either disappear altogether or are pushed to the back of the list. Opinions change, ideas change, your attitude changes, lifestyles and life choices change and your body changes. If your martial arts training is grown up enough and has scope and depth there will be room for changes of opinion or even changes in lifestyle.

If your martial system has the hallmark of a certain maturity to it then lives and opinions can flex comfortably within the framework of the system. The irony is that viewed from the outside Japanese Budo may look rigid and locked in its bubble, but this should not be the case. Budo should help to make better people and it is my view that it can act as a lens to help you address some of the bigger existential issues in life.

But understanding what goes on inside the world of Budo is not easy, even though we tend to reach for easy descriptions. Human lives are just as complex if we live in Western Europe or the Far East.

To bring it closer to home; when we try to get a handle on what Ohtsuka Sensei was thinking when he devised the Wado Ryu, we have to place our thinking in a Japanese context. Things don’t happen in a vacuum; creations such as Wado Ryu are influenced by all manner of cultural forces. When Ohtsuka Sensei first presented his creation it wasn’t to the world, it was to the Japanese Budo establishment, the world had to come later. This creation did not spring fully formed; it was refined over subsequent decades, even today there are people who cannot comprehend this idea of refinement over time and want to preserve Wado in a time capsule. If the Art world had allowed such a thing to happen artists would be scrawling on cave walls!

Like Art Wado moved on and still continues to move. But I think that where Wado has an advantage over other martial arts who may be struggling to move forward or even survive, is that its key principles are simple. In Wado there are no flowery extras, no pseudo mystical obfuscations, the rules are easy to understand – it’s the ‘doing them’ bit that is difficult.

Tim Shaw

“If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”.

Both Abraham Maslow and Abraham Kaplan are credited with the phrase “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”. I have seen this phrase used as a great leveller in discussions relating to martial arts training, particularly when someone’s entrenched ideas need a good shake up.

In 1964 Kaplan called it ‘The Law of Instrument’ and it is used to describe the tendency towards very narrow explanations. Although it has negative connections it can be a useful litmus test for our own ideas and assumptions.

I remember getting into a discussion about punching in Wado and trying to suggest that there was more going on than just the idea of developing punching power. The person I was discussing this with was very much of the opinion that power punching was the only reason we operate Junzuki and Gyakuzuki the way we do. I have to admit that in my early years of training that was the way I thought too. Any kind of strike had to have as its one single goal destructive power. Later on I was to meet people from other styles who also used blocks as strikes – I liked the idea and started to use forearm conditioning training, until I smartened up and realised that I was just inflicting damage on myself for short term gain.

For me it took an embarrassingly long time to shake these ideas off. ‘More speed more power’ didn’t cut it any more. The idea of turning myself into the human version of an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile was all beginning to look like a juvenile fantasy. But it is an argument that is bolstered by the view that the destruction of our ‘enemy’ using only our fists and feet is our sole objective – that is, the ‘hammer’ approach.

But our Wado toolbox is a much more interesting and sophisticated place; yes I’m sure there is a hammer in there; in fact there is more than one kind of hammer in there, but there are far more subtle tools. Some tools at first glance look bewildering complex, some, annoyingly simplistic yet still do not easily reveal their usage.

But to continue the analogy; being shown the tools or even laying your hands on them for the first time does not mean that you can use them effectively. Like a good workman on the job, there is a lot of accumulated knowledge that comes into play even before the toolbox is properly opened, and practice and reflection, as well as learning from those more knowledgeable than ourselves are essential to becoming a skilled craftsman.

Tim Shaw

Old Bull and Young Bull.

For those of you who know the joke about the old bull and the young bull contemplating a neighbouring field of heifers, I won’t bore you by retelling it. For those of you who don’t know it, Google it.

But basically it’s a parable highlighting the benefits of age and experience over youthful enthusiasm.

So… how to relate that to a martial arts situation?

Look around most well established Dojos and you’ll see a range of ages and grades. But it’s not the spread of grades that interests me, it’s the age demographic.

Personally I find that as a rule the more mature person can often be the better student. Yes their flexibility and general physical condition will not be as good as the youngsters, but their life experience and knowledge of their own capabilities tends to be more grounded. Mentally they are generally able to evaluate their developing knowledge and skills in a more mature way, and as long as they are able to ‘empty their cup’, their capacity to digest the more complex ideas is greater than most people half their age. For Wado this is a great advantage. The late Reg Kear described Wado Ryu as ‘a thinking man’s karate system’, and the more you climb the tree the more there is to take on board. Not that we should get carried away with the cerebral aspect of what goes on in a Wado Dojo, because it’s no good just having it in your head, you have to be able to physically do it. The intellectual and the physical in Wado are like two wheels on an axle; one without the other would make forward motion impossible.

I remember in the long distant past a particular Sensei criticizing another Sensei’s karate as ‘old man’s karate’, I didn’t buy it then and I don’t buy it now. But I believe there is a maturity in karate practice.

A 5th Dan’s Pinan Yodan should look quite different than one performed by a 1st Dan. As long as the mature karateka has kept their training consistent and not wrecked their body through silly training methods they have the capacity to work towards the higher ground.

But what about the youngster?

Twenty year olds should train and fight like twenty year olds, not like fifty or sixty year olds. All experienced Sensei should see this and create training opportunities that are age-appropriate. I always think of my cat and what he taught me. When he was a kitten he would frantically climb the curtains. Why the curtains, there’s nothing up there, I wondered? Answer; because he’s a kitten, a fizzing ball of pent up energy looking for an outlet. I ask all the senior experienced instructors; what were you like when you were twenty?

I suspect you were like the young bull.

Tim Shaw

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2